Historical Background

The Open Range Cattle Era

For several generations the cowboy has been a favorite among American folk heroes. He has been romanticized and glorified. In the process his fictional and television images have obscured the major contributions of the open range cattle industry to the development of the West.

TEXAS ORIGINS

The cattlemen's empire of the post-Civil War period had its origins deep in south Texas in a triangle bounded by the cities of San Antonio, Corpus Christi, and Laredo. Nature seemingly had endowed this region with the specific resources for raising cattle. The climate was mild, the grass grew tall, and predatory animals were few. Northward lay a vast expanse of grassland awaiting occupation; it was guarded only by the Indians, who in a sense were tending their own herds—the buffalo.

|

| The vast buffalo herds that ranged over the Plains supported the Indian economy. As the buffalo hunters completed their work, U.S. Army troops forced the Indians onto reservations. Shown here is part of the herd maintained today at Theodore Roosevelt National Park. |

The establishment of the Texas missions by the Spaniards, beginning in 1716, marked the first effort to raise cattle in the province. By 1770 the ranches of Mission La Bahia del Espiritu Santo, near Goliad, were running perhaps 40,000 Longhorns between the Guadalupe and San Antonio Rivers. Soon the cattle constituted the principal wealth of the missions and of most of the private citizens in the province, who made long drives from Texas to Louisiana and Coahuila. In south Texas sheep increased more slowly than cattle because the area was thickly wooded and because of the shortage of trained herders.

The Spanish also introduced Longhorns into present Arizona and New Mexico at an early date, but because of the less suitable environment no significant development of the cattle industry occurred in the region until after the Civil War. In California, where Longhorns also prevailed, ranching was the basis of the economy during the Spanish and Mexican periods, but it played no real part in the development of the cattlemen's empire in the American West.

LONGHORNS: THE BASIC STOCK

The Longhorn, more a type than a breed, first stocked the ranges in what is now the United States. Despite his nondescript color, coarse and stringy meat, and wild nature, he was of distinguished ancestry. He was a direct descendant of the unseemly, lanky animals that had been reared for so long in Spain by the Moors on the plains of Andalusia.

Early American settlers in Texas considered the Longhorns to be indigenous wild animals like the buffalo. They called them "mustang cattle," "Spanish cattle," or simply "wild cattle." The cattle brought by the settlers from the Eastern United States interbred with the Longhorns. The result was an animal slightly different than the original Longhorn: the horns were longer, the body heavier and rangier, and the color variations unlimited. By the Civil War period the words "Texas cattle" and "Longhorns" had come to be synonymous.

Cowboys declared that the wiry Longhorn steer, despite his perversity and independence, was the most likely animal for trail driving that nature ever produced. They claimed that the long-legged animals had tougher hooves, more endurance, and the ability to range farther without water than the cattle of improved blood—the "high grade stuff" of a later period. A natural-born "rustler," the Longhorn seemed to thrive on the trail. He walked tirelessly over great distances, seemingly unaffected by heat, hunger, or the unmelodious songs of the nightriders. And above all he could walk 60 miles between waterings. These virtues compensated in part for the distressing inability of the breed to produce beef in quantity or quality.

|

| Vast herds of Longhorns, driven north from Texas, once grazed Western ranges. Pictured here are Longhorns at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, near Cache, Oklahoma. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service maintains another herd at Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge, Valentine, Nebraska. (Courtesy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.) |

THE SPANISH MUSTANG

Another important contribution of the Spaniards to the cattle industry was the mustang, which, like Spanish cattle, soon had a better hold on U.S. soil than the Spaniard himself. This horse, whose bloodlines were strong like the Longhorn, was descended from stock brought into Spain from North Africa by the Moors. After the Spanish brought the mustangs to the Southwest, some of them strayed, multiplied, and formed wild herds that eventually ranged onto the Great Plains. The Indians preferred stealing from the Spaniards to catching the fleet-footed, untamed animals on the prairies.

The Texas vaquero, or cowboy, found the mustang a natural-born cow horse. Of scrubby appearance and slight stature, the horse had been radically changed by the Spanish. What he lost in beauty, he gained in wind and bottom. When the American cowboy first came to know him, he was a wiry, fleet, untamed little brute who could run all day and still kick his rider's hat off at night. Through selective breeding and the admixture of some imported blood, in the course of time he became larger and somewhat more tractable.

OTHER SPANISH CONTRIBUTIONS

The Spaniards provided almost all the ingredients of the open range cattle era, except for grass and water. Besides the Longhorn and the mustang, the hackamore, or jaquima, was also Spanish in origin, as were the lariat, or la riata, the sombrero, and the chaps, or chaparejos. The so-called Texas saddle, almost in its present form, was introduced into Spain by the Moors. Finally, Spain perfected the techniques of handling cattle on horseback.

|

| Range crew on the Pecos River, New Mexico Territory. (Courtesy, Museum of New Mexico.) |

SEEKING A MARKET

At the conclusion of the Texas Revolution, most Mexican ranchers in south Texas abandoned their property—including cattle—and hurried southward to avoid the vengeance of the Texans. The new republic promptly declared all unbranded stock to be public property. Impoverished Texas pioneers who provided themselves with a good supply of branding irons and wielded them with vigor were soon on the way to becoming cattle barons. But Texas had insufficient markets for the cattle.

Before the Civil War the largest single market was New Orleans, reached both overland and by water, although the overland route was the more popular. In 1853 alone an estimated 40,000 head crossed the Nueces River en route to New Orleans. The California gold rush provided a new market. In the early 1850's cowboys drove thousands of Longhorns, worth $5 to $15 a head in Texas, across the desert to California, where they brought up to $150 each. The enormous difficulties encountered on the long drive to California, however, prevented it from becoming a major market.

|

| Kansas City Stockyards in 1872, the second year of operation. Varicolored Texas Longhorns, forwarKansas City Stockyardsded from railhead cowtowns over the Kansas Pacific Railroad, await shipment to Chicago and other points. (Courtesy, Kansas City Stockyards Company.) |

Another small but promising market became apparent in the frontier towns, mainly in Missouri, where parties bound over the Oregon Trail outfitted. Texans drove herds of cattle northward and then sold them to local butchers, Chicago and Kansas City meatpackers, and the commissary department of the U.S. Army. In 1854 about 50,000 head of Longhorns crossed the Red River. But these markets were irregular and minor ones. Much better ones had to be found.

Then came the Civil War, and Texas cowboys dropped their branding irons and took up shooting irons. While they were at war, the Longhorns increased to about 5 million head. At the same time the cities of the North, rapidly expanding and becoming industrialized because of the wartime boom, were hungry for meat. When Texans returned from the war, they found their Confederate currency worthless and their economy wrecked. But they did have beef—worth only a few dollars a head, or even free to anyone who was willing to go out and round it up—but beef that would bring $40 a head in Northern and Eastern markets, with which Texas had no rail connections. The $4 steers had to be connected with the $40 markets.

Such a connection was facilitated by various trends in the last half of the 19th century: The removal of the buffalo and the Plains Indians; the extension of the railroads across the West; and increased demand for meat. This demand was not only in the cities of the East, which resulted in the burgeoning of the Chicago and Kansas City meatpacking industries and the development of the refrigerator car, but also in mining areas, U.S. Army posts, Indian reservations, and railroad construction gangs in the West.

THE GREAT DRIVES

In the spring of 1866 a few Texas ranchers drove herds of Longhorns northward over the Shawnee Trail. Their objective was Sedalia, Mo., the railhead for Eastern and Northern markets. But the first year of the "long drive" was nearly the last. Not yet experienced in trail driving, the cowboys found the half-wild cattle difficult to manage. Armed mobs of angry Missouri farmers, halting the drives at county lines, shot at and stampeded the cattle for fear that the herds would infect their own animals with the dreaded Texas fever.

|

| Jesse Chisholm, half-breed Cherokee trader, founded the route across Indian Territory into Kansas that became a famous cattle trail, the Chisholm Trail. (Courtesy, Oklahoma Historical Society.) |

It was Joseph G. McCoy who made perhaps the most important single contribution to the range cattle industry. This young, audacious cattle dealer found an effective way to bring Texas cattle to market. In 1867, when the Kansas Pacific Railroad reached Abilene, a few Texans began to drive herds there. McCoy, recognizing the economic potential of the Texas cattle drives, established shipping facilities at Abilene. He did so because he felt that it was the farthest point east that would be practicable and because it was well watered and had a good supply of grass.

McCoy finally persuaded the railroad that his plan was sound, and he spent the summer of 1867 building stockyards, pens, and loading chutes. He advertised the market throughout Texas and sent his agents into Kansas and Indian Territory (in present Oklahoma) to guide the trail herds to Abilene. After crossing the Red River the cowboys followed the broad trail that Jesse Chisholm, a half-breed Cherokee Indian trader, had used earlier on trading expeditions and had freshly marked while guiding a military expedition that was removing about 3,000 Wichita Indians from Kansas to a new location along the Red River. Thus was born the Chisholm Trail.

In 1867 only 35,000 head of cattle reached Abilene, but a new era had begun. Returning drovers spread the word throughout Texas of the ease with which cattle could be driven to Abilene and pointed out that few settlements, wooded areas, or angry farmers would be encountered along the way. In the next 4 years more than a million head of Texas cattle were loaded at Abilene and shipped to Chicago and Kansas City packinghouses or as feeders to Iowa, Nebraska, Missouri, and Illinois farms for fattening on corn. Then the advancing farmers' frontier made it necessary to shift the long drive westward once again. Newton and Wichita, on the Santa Fe Railway, became the major termini of the drive.

|

| Pile of 40,000 buffalo hides awaiting shipment in Dodge City, Kansas, to Eastern markets. As the buffalo hunters wrought destruction on the Plains, they destroyed the Indian way of life but opened the way for the farming and ranching frontiers. (Courtesy, Kansas Historical Society.) |

The next major trail to develop was the Great Western, or more simply, the Western. Its railhead was Ogallala, Nebr., served by the Union Pacific Railroad, and by 1876 the Western had supplanted the Chisholm Trail as the major northward artery of cattle traffic. By 1880 Dodge City, south of Ogallala and located on the Santa Fe Railway, had replaced Ogallala as the major railhead of the Western Trail. But the latter city was used until 1895, and the trail was extended northward into Montana, for cattlemen had discovered that cattle could survive northern winters. Ranching was spreading, and Texas no longer was the major source of range beef for the Nation.

Despite evidence to the contrary, most Texas ranchers had long refused to believe that cattle could survive the cold winters on the northern Plains or in the mountains. Mining communities of the 1850's and 1860's in the widely separated mountain districts of the West had drawn cattlemen and sheepmen to supply meat. These ranchers usually operated on a small scale and supplied a limited market. Large-scale freighting companies that supplied the necessities of life for the miners and the Army had also brought animals West and wintered them along the overland routes. For example, during the winter of 1857-58 the freighting firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell wintered some 15,000 head just south of the Oregon Trail.

Colorado also served as proof, for it early became a center of the cattle industry—partly as a result of the Pike's Peak mining boom that began in 1858 and partly as a result of the gradual extension northward of Texas ranches. In 1866 Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, two Texas drovers and ranchers, founded another major trail, the Goodnight-Loving. They trailed large herds from Fort Belknap, in Texas, into Colorado Territory via Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory. And in 1868 Goodnight delivered a trail herd to Cheyenne, the second Texas herd to arrive in Wyoming, to feed the army of workers on the Union Pacific Railroad.

With the arrival of the Kansas Pacific Railroad late in the 1860's, ranchers in eastern Colorado Territory could ship cattle to the Eastern market or drive them to the ranges in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming—where the nucleus of a cattle industry had already been established to satisfy local markets such as miners, overland emigrants, and Army forts, and where young stock was especially in demand. By 1869 a million cattle were grazing within the borders of the Colorado Territory and many predicted that it would become "the cattle pasture of the world."

|

| Chuckwagon on the move. Bedrolls stacked to the wagon bows and dishpan banging behind, the lordly cook drives to the next camp. Photograph by Erwin E. Smith. (Courtesy, Mrs. L. M. Pettis and the Library of Congress.) |

Despite proof that Longhorns could survive cold winters, most Texas ranchers refused to believe it until they saw for themselves—and see they did. In the spring and summer of 1873 they drove several hundred thousand cattle north along the Chisholm Trail, but at Abilene they found few buyers. The Panic of 1873 had hit the Nation. Rather than drive the cattle back to Texas, the drovers left them on the prairies of Kansas and Missouri with the expectation that they would die during the winter. But in the spring, when the drovers returned, they found that the Longhorns had not only survived but had improved.

It became apparent that steers maturing in the north fattened more than in Texas. For this reason, and with proof in hand that the animals could survive, many of the bigger Texas spreads began branching out northward. They continued to use their Texas ranches as breeding places, but they maintained finishing ranges in the northern territories. Texas cattle were trailed a thousand miles to "double-winter" on the grass ranges of Wyoming, Montana, or Dakota, and then shipped to the Chicago slaughterhouses. Northern ranchers also obtained substantial numbers of cattle, English breeds, driven eastward over the mountains, from Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

The Texas cowboys who pushed the cattle northward were full of exuberance and confidence, though they faced heat and thirst, stampedes and Indians, rustlers and armed homesteaders. They were the men who established the range cattle industry on the Great Plains and in the Rocky Mountain States. They taught their trade to the cowboys there just as they had learned it from the Mexicans and the Mexicans from the Spaniards. Such prominent cattlemen as Teddy Blue Abbott, Charlie Siringo, and Granville Stuart, along with a host of others, have testified that development of the open range cattle industry was from first to last largely a Texas story.

|

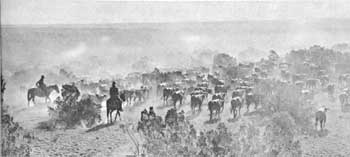

| In the dust with the "drags"—weaker cattle that dropped behind the drive. As the day lengthened, so did the thirst of the cowboys. Photograph by Erwin E. Smith. (Courtesy, Mrs. L. M. Pettis and the Library of Congress.) |

The organization and routine of the trail drive was a serious business. As many as 2,500 cattle were collected in south Texas and consigned by the owners to the care and authority of the trail boss for delivery at a railhead or stocking ranch, which might be 1,500 miles or more distant. Ten to twelve hands handled the herd, along with the cook and a youthful apprentice who cared for the remuda of a hundred or more horses. The cowboys sometimes spent 14 to 16 hours a day in the saddle—hard, lonely, and monotonous work—for $30 a month and board.

The long, sinuous line of Longhorns, stretching out like a long multicolored ribbon, soon became broken to the trail, and the daily routine became automatic. The trail itself, because of the passage of hundreds of thousands of cattle, was easily recognized and easily followed. Depending in part on the grass available, it consisted of scores of irregular cowpaths that formed a single passageway, which widened and narrowed and twisted and turned according to the terrain—but led ever northward.

The number of cattle driven north each year was large. In the peak year 1871, cowhands probably drove 700,000 Texas cattle to Kansas railheads, and between 1866 and 1885 millions of head moved to the railheads and northern ranges. In the level and open country drovers were seldom out of sight of other herds. From a hilltop in Nebraska, one cowboy saw 7 herds to the rear of his own and 8 in front. While the dust of 13 more could be observed across the North Platte. "All the cattle in the world seemed to be coming up from Texas," he declared. When a thunderstorm stampeded 11 trail herds, including about 30,000 Longhorns, which were waiting to cross the Red River at Doan's Store in 1882, it took 120 cowboys 10 days to unscramble the cattle, reassemble the herds, and get them moving again.

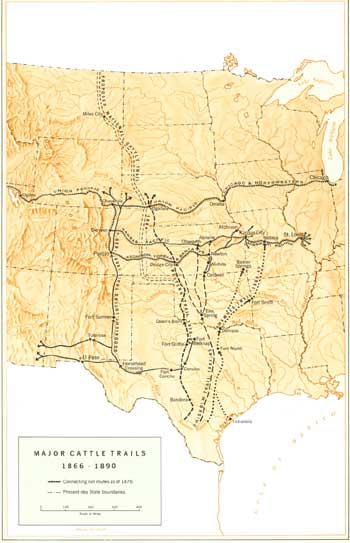

|

| Major cattle trails, 1866-1890 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

FENCES, QUARANTINES, AND INDIANS

The trail herders usually met bitter opposition from the farmers of Kansas and Missouri, resentful because the Texas, or Spanish, fever ravaged their small herds and milk cows. The Longhorns seemed to be immune, but the fever tick that rode north with them was a menace to all other cattle. To protect local herds, farmers organized vigilance committees to prevent passage of the Texas stock. Quarantine lines, established by State legislatures, were an important factor over the years in forcing the cattle drives farther and farther westward.

The westward-tending Kansas farmers became still another problem. Their small, enclosed homesteads soon began to present an almost unbroken fenceline. The farmers also plowed furrows around their farms and claimed damages when the herds were driven over these "fences." They also fenced waterholes and charged a toll for the watering of cattle. If alone, the farmer was helpless, but as agricultural settlements increased on the trail, 20 farmers armed with shotguns were sufficient to force the Texas cowboys to pay the fee.

The Indian Territory presented another barrier. The Five Civilized Tribes resided in the valleys of the Red, Arkansas, and Cimarron Rivers, squarely across the cattle trails. To protect their pasturage and raise revenue, they levied tolls and defined the trails that could be used. Conflict and friction were inevitable and frequent.

The Indian barrier, the quarantine laws, and the advance of the farming frontier pushed the trails steadily westward. The Texas Panhandle eventually became the route to the railheads, and eastern Colorado the pathway to the northern ranges. In 1884 a national convention of stockmen adopted a resolution urging Congress to establish a National Cattle Trail, a permanent road 6 miles wide extending from the Red River to Canada. But the rapid building of railroads and the fear of overstocking the northern ranges helped defeat the proposal.

THE PUBLIC DOMAIN: GRASS AND WATER

The direct cause of the widespread demand for Texas cattle in the northern territory was the ready availability of the lands of the public domain. These lands were open in the sense that they were uncontrolled and unfenced. The laws that Congress passed to encourage orderly settlement of the public domain were, to a great extent, unenforced and evaded. The open range included all or part of seven States, eight Territories, and Indian Territory. It comprised about 44 percent of the total land area of the United States.

This was land that the farmer—accustomed to the timbered, well-watered East—could not farm with his usual methods and machinery. This was land that the Plains Indians and the buffalo had called home for many generations. The demise of Indian power in this region coincided with the slaughter of the great buffalo herds, on which the Indian economy depended. Just after the Civil War, buffalo hides became valuable for their leather, and the hide men did their bloody work exceedingly well and amazingly fast. In 1880 the last buffalo herds were sighted on the southern plains and only a few years later in the north. The Plains tribes took to the warpath, the troops clashed with them, and many soldiers and braves died before the reservations became the home of once-proud tribes of Indians.

|

| Water was as necessary as "free grass and air" to the Western rancher. Most Plains streams seasonally rose and fell. Photograph by Erwin E. Smith. (Courtesy, Mrs. L. M. Pettis and the Library of Congress.) |

The Government had no immediate use for these public lands, which could be appropriated by the first men to occupy them. The land constituted "free grass" and "free water," collectively known as "free air." To this open range were trailed hundreds of thousands of cattle, almost all driven up from Texas as yearlings and 2-year-olds. There they were crossed with Eastern cattle, fattened on the "free air," and sold for high prices at the nearest railhead. With little more than a few skilled cowhands and a branding iron, a man could convert the grazing land into top steers and grow rich.

RANCH LIFE

The process by which a man became a rancher was not complicated. Finding a live stream, hopefully with natural boundaries surrounding it to hold his cattle, the prospective rancher claimed the land along the stream for 10 to 15 miles and as far back as the water divide. If a waterhole was the only source of water in the vicinity, he selected his lands around the hole and effectively controlled all the surrounding acres of grass. Proof of ownership, although tenuous, was not often contested until the homesteaders arrived. Under questioning a rancher might refer to one of the Federal laws, such as the Homestead Act or the Desert Land Act, but he usually advised those so inquisitive and foolish as to ask proof of ownership to "vamoose the ranch" or "pull your freight, pronto."

At first ranch life was hard and lonely. The pioneer rancher subsisted largely on beans, bacon, and coffee. He fought Indians, wolves, blizzards, rattlers, rustlers—and his own kind. But he also watched his cattle fatten and multiply and hired cowboys to tend them. For some hands it was a 100-mile ride from the bunkhouse to the front gate. Later a ranchhouse and scattered outbuildings would replace the wickiup, and other evidences of civilization would follow.

The cattle kings were men apart—men such as John Chisum, Granville Stuart, Charles Goodnight, and John Wesley Iliff. They were strong men—men who conquered the West. What they accomplished was done literally with their bare hands. They endured as many dangers and hardships as any man on any frontier. Little wonder that they later would look back with such pride at what they had done.

|

|

| Colorado rancher John W. Iliff purchased foundation stock from Oliver Loving and Charles Goodnight. His herds grazed thousands of acres in the South Platte Valley. (Courtesy, Western History Collection, Denver Public Library.) | Charles Goodnight, cofounder of the Goodnight-Loving Trail, was one of the first cattlemen in the Texas Panhandle. (Courtesy, Western History Collection, Denver Public Library.) |

|

|

| Granville Stuart, pioneer Montana cattleman, was a leader of the Vigilance Committee, organized in 1884 by ranchers in Montana Territory to protect their stock. (Courtesy, Montana Historical Society.) | Joseph G. McCoy, cattle dealer, established cattle shipping facilities at Abilene in 1867 and encouraged Texans to make the first drives to Kansas railheads. (Courtesy, University of Illinois Library.) |

BOOM ON THE RANGE

About 1880 the range cattle industry entered a boom period. The rush to the cow country was in many ways similar to the rush to the goldfields. The cause certainly was the same—the prospect of quick wealth in a new country that seemed to offer unlimited opportunity for the ambitious. "Cotton was once crowned king, but grass is now," declared an Eastern livestock journal.

The stampede to the cattle lands was literally worldwide. It attracted boomers from the East, from Canada and Australia, and from the British Isles. Youths from Eastern farms and factories, savings strapped to their waists, eager for wealth and adventure, packed the trains. The mania spread to Europe. When an English parliamentary committee reported a 33-percent return to stockowners, the desire to participate in the profits of American ranching, personally or as an investor, became a craze among the British.

As British capital had been involved in the mining frontier and had helped build the American railroad system, so it figured prominently in the growth of the range cattle industry. The largest cattle companies operating in the United States in the 1880's were formed in England and Scotland. British investors followed Horace Greeley's advice to "go West"—at least they sent their money in that direction to the amount of $17 million during the short-lived boom. Gouty squires who may or may not have known the difference between a steer and a heifer discussed the niceties of the spring roundup over port and nuts.

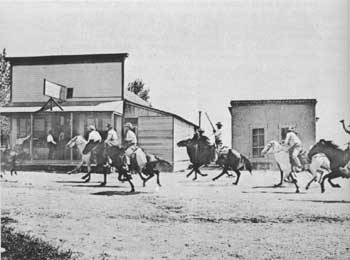

|

| Some thirsty hands ride into town. The life of the cowhand was mostly work and little play. Photograph by Erwin E. Smith. (Courtesy, Mrs. L. M. Pettis and the Library of Congress.) |

Proper Bostonians and staid New Yorkers joined the rush to invest in the cattle industry. In a single year 20 corporations, capitalized at more than $12 million, were organized under Wyoming laws. In some transactions the buyer never saw a head of his purchase, nor possessed more than a fraction of the purchase money. Uncontrolled speculation ensued. Swindlers flourished, and paper companies without an acre of land or a single steer sold stock to a gullible and eager public.

Nor could the tally books of brokers always be trusted. When ranchers sold large herds, the transactions often represented little more than rough estimates of the cattle involved, a generous figure being inserted for the year's calf crop and on rare occasions an allowance for losses from severe winters, diseases, or other causes. Such a system gave rise to many stories, such as one that made the rounds in Cheyenne. A group of cattlemen purportedly bellied up to a local bar during a long, hard winter and were gloomily speculating on their probable losses. "Cheer up, boys," said one, setting up drinks for the house, "the books won't freeze."

After 1880 the demand for cattle to stock the northern ranges, which increased yearly, taxed the available supply and drove prices upward. Texas ranchers sent increased numbers of head northward, but the demand was still greater than the supply. "Cattle, cattle, more cattle" was the slogan of the grass country from north Texas to Canada. Answering this call, in 1884 trail drivers pointed north approximately 416,000 head of Texas cattle, the greatest number since 1871.

|

| Cattle raising was dangerous in arid country. In a bad year the results were disastrous. This photograph was taken in Roswell, New Mexico. (Courtesy, National Archives.) |

BEGINNING OF THE END

Because of the enormous flow of capital into the cattle country, the high prices, and the spectacular profits, there could be but one result: the number of cattle would soon exceed the carrying capacity of the range. In a word, overgrazing would result. Alarmed cattlemen began to fear for the future. There was no natural limit to the number of cattle that could be bred in Texas and sent up the trail, but even the celebrated Longhorn could not fatten on air alone. The good pastures were being overgrazed, the marginal lands were crowded, and no new area of grass was available for an escape valve. The arid country, devastated by winter blizzards, could support the vast herds only under optimum weather conditions. One bad winter would ruin thousands of investors and ranch owners and kill millions of cattle. As the first half of the 1880's passed, each spring cattlemen accepted their winter losses, being thankful that the toll was no greater. But the development of the sheep industry and the invasion of the homesteaders were even greater threats than weather conditions.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/prospector-cowhand-sodbuster/intro4.htm

Last Updated: 22-May-2005