Historical Background

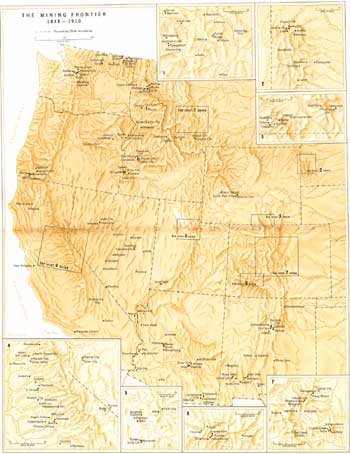

Spread of the Mining Frontier

Almost as soon as the California gold rush got underway, prospectors began extending the search for new bonanzas. Eventually their hunting grounds became the entire West. For the true prospector, any other life was unthinkable. He was imbued with a feverish restlessness. For him, as for the mountain man who had preceded him, the settled and secure life was boring beyond toleration. With a washing pan, a grubstake, and endless hope, he climbed the mountains and tramped the deserts. He panned each promising stream and anxiously scanned each outcropping of rock for a telltale glint. The trial-and-error experience of California supplied the knowledge, experience, machines, and equipment needed to exploit other fields. Ex-California miners sought and found new El Dorados in the remote parts of the Rockies, the Great Basin, and the Colorado and Columbia Plateaus.

During the 1850's, while the prospectors were feverishly ranging over the hills and up and down the rivers searching for gold, politicians excitedly paced the floors of Congress as the storm clouds of the slavery and secession issues gathered over the Republic. Logic and reason yielded to inflamed passions and emotions, and honorable men of both the North and South turned to the sword and the gun to settle their differences. But in the West the thought of quick riches prevailed in the minds of most men, who did not lay aside the pick and shovel for deadlier weapons. California and Colorado sent token forces, but by and large it was business as usual in the goldfields. The pursuit of mineral wealth continued unabated.

When the war ended, the triumphant North did not resume its former unhurried pace. The era of frenzied finance and industrialization had arrived. Gold and silver were needed to underwrite the cost.

ARIZONA—APACHES, SILVER, AND COPPER

The first region where ex-Californians struck it rich was the Southwest. The mineral resources of the region, unlike those of California, had been known for centuries to the Indians, Spaniards, and Mexicans. In 1825 the copper mines at Santa Rita, in the present State of New Mexico, had been leased to an American fur trapper, Sylvester Pattie. And rumors of more exciting metals—of gold and silver—had persisted from the days of the conquistadors; every locality boasted at least one "lost mine." Despite the hostility of the Apaches, the rumors continued. In 1850 the U.S. Army constructed Fort Yuma at the junction of the Gila and Colorado Rivers, and 3 years later the Gadsden Purchase added the southern parts of present Arizona and New Mexico to the United States.

Even before the United States officially took possession of the area of the Gadsden Purchase in 1856, Americans began to comb it for riches. Charles D. Poston, who came from San Francisco in 1854, and Herman Ehrenberg discovered gold and silver deposits in the mountains around Tubac, in present Arizona. They also came across the Ajo copper mines and reopened them. These mines, which portended the great mineral wealth of Arizona, had been worked by the Indians, Spaniards, and Mexicans, but had been abandoned in the 1840's. The Americans worked them from 1854 until 1861, the ore being shipped to Wales for smelting. The mines then lay idle until the 20th century.

In 1860 Sylvester Mowry, an ex-Army lieutenant and West Pointer, made a strike in the nearby Santa Ana Mountains. Soon Arizona, which became a Territory separate from New Mexico in 1863, attracted more than its share of the criminal element. Tucson, the center of mining operations, became known as the "paradise of devils," a designation not lightly won in the mining era of the West. The miners had as neighbors the fearsome Apaches, led by Cochise, who in 1861 went on the warpath and forced the miners to abandon the district temporarily.

The capture of southern Arizona by the Confederates at the outbreak of the Civil War, in 1861, temporarily ended mining, but the following year Federal troops reoccupied the area and mining activities resumed. Before the war ended, mining was further stimulated by gold strikes near Prescott and Wickenburg. Silver discoveries in 1876 near Superior and Globe caused a new silver boom. This was given special impetus in 1877 by Ed Schieffelin's bonanza strike, in the Apache-infested San Pedro Valley, which resulted in the founding of the colorful and lawless town of Tombstone.

Although Arizona gained national prominence from its production of silver, copper proved to be its most important mineral resource. The mining of copper began in 1871 in the Morenci district of eastern Arizona, and in 1877 in the Bisbee and Jerome districts. Bisbee also had gold and silver resources. In 1878 prospectors discovered copper at Globe. By the 1880's—when the coming of the railroads opened a new era in Southwestern copper mining—two copper industry giants, the Calumet and Arizona Mining Company and the Phelps-Dodge company, were production leaders.

|

| The Mining Frontier, 1848-1910 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

COLORADO—"PIKE'S PEAK OR BUST"

The small initial strikes in Arizona were insignificant when compared with the discoveries in Colorado and Nevada. Gold and silver continued to be found all over the West for more than half a century following the strike in California, but the most exciting discoveries were made within a decade. In the summer of 1858 several groups of prospectors—some veterans from Georgia and California and others who were greenhorns from Kansas and Missouri—were working along the Continental Divide in western Kansas Territory when some of them struck gold near Pike's Peak. Before winter set in they founded Denver City.

News of the Pike's Peak discovery soon found its way eastward to the Mississippi Valley, where the Panic of 1857 insured its welcome. Accounts of the Colorado strike spread like wildfire through the border settlements—and with the same effect as the news from Sutter's mill a decade earlier. Poverty-ridden frontiersmen, unemployed workers, and unsuccessful businessmen eagerly scanned exaggerated newspaper accounts of the new El Dorado. Pike's Peak was only 700 miles from the Missouri River and required no grueling trek over mountains and deserts as had the California trip. The rush to Pike's Peak in the spring of 1859 was one of the wildest in the Nation's history.

Gold seekers used almost every type of conveyance to get to the scene of the strike. Some used the heavy prairie schooner wagons, others the light carriages of the border country; some went by horseback and carried their goods on pack animals; others, copying the Mormon migration, pushed two-wheeled handcarts. By the end of the summer many thousands of "fifty-niners" had passed through Kansas and Nebraska en route to the mountains and the gold. These enthusiastic pilgrims contributed one of the famous slogans of U.S. history: "Pike's Peak or Bust"—crudely lettered on their packs and wagon canvas.

When the emigrants arrived, they found that the newspapers and guidebooks had been somewhat deceiving. Panning every stream, chopping away at every rock outcropping, they found little. In the jargon of the times, they had been "humbugged." One of the greatest booms in American history gave way to one of the quickest busts. By midsummer of 1859 half of the would-be miners who had rushed to Colorado were back home. Below the hopeful slogan on the white canvas of the prairie schooner appeared a new one in bolder, darker letters: "Busted, by God"—an eloquent epitaph to one of the major fiascos of the frontier.

Ironically, soon after most of the disillusioned "fifty-niners" had returned eastward, prospectors made major gold strikes. The early boom failed not because of a lack of gold but because of its elusive location. The placer dust, panned from creek bottoms, soon played out. The rich quartz lodes from which the dust had broken loose were located upstream. These lodes, however, were so refractory that mining required major outlays of both capital and labor, which only companies could provide. As one prospector said, while watching the diggings and operations at a stamp mill, "Hell, I expected to see them backing up carts and shoveling it [gold] in." But stamp mills and tunnels were signs of the future in mining.

|

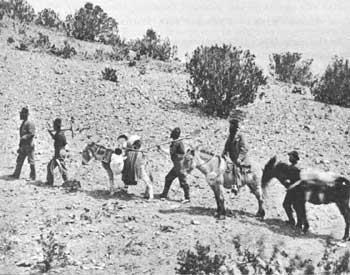

| Prospectors in Cunningham Gulch, Colorado Territory, in 1875. They lived a rugged and lonely life. (Courtesy, National Archives.) |

The second great Colorado boom occurred in the late 1870's, when prospectors made fabulous silver strikes at Leadville and Aspen. Colorado and silver became synonymous for a time, and the "Bonanza Kings" crashed the jealously guarded portals of the U.S. Senate. In the 1890's a third boom occurred. Gold discoveries on Cripple Creek—one of the richest of all goldfields—attracted the attention of the entire world.

NEVADA—THE COMSTOCK BONANZA

In 1858, the year of the Pike's Peak discovery, prospectors ranging over the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada above the Carson River Valley stumbled upon a concentration of minerals rich beyond all belief—the Comstock Lode. Named for one of the discoverers and founders of the Ophir Mine, Henry T. P. Comstock, the lode did not at first seem so promising. Those lucky enough to obtain "feet" in the area were hindered in their attempts to extract gold by a blackish substance that encased the yellow metal. Sent to California to be assayed, the "black stuff" proved to be almost pure silver.

Bars of silver from the Ophir Mine, when displayed in San Francisco, brought on the usual craze to "see the elephant." By the fall of 1859 thousands jammed the tortuous roads over the mountains to Nevada en route to the Washoe District, as the area of discovery came to be called. Carson City, just off the California Trail, and Virginia City, at the site of the Ophir Mine, became leading mining centers.

The newcomers were soon frustrated. Individual miners had little opportunity. The minerals were locked in quartz veins, which could be worked only with expensive machinery. Yet scores of promoters and stock salesmen peddled "feet" in imaginary mines and sold shares in companies that did not exist. Mark Twain was one of those who arrived in Carson City soon after the initial strike and who traded "feet" with the best of them.

As capital flowed in and companies began operations, the promoters realized their wildest dreams. Less than a dozen of the 3,000 mines staked out ever produced, but their profits were such as to sustain the hopes of all, and to provide Virginia City with a group of newly rich citizens whose antics were as legendary as the profits of the mines. Ornate mansions rose from the desert hills; more than 20 theaters provided cultural relaxation. Meanwhile, every new discovery launched a period of wild trading in "feet."

In their efforts to develop the discoveries the miners altered the face of western Nevada considerably. They laid out roads over the mountains to California, for everything had to be freighted in from the outside. They almost denuded the eastern slopes of the Sierra and the shores of Lake Tahoe of timber for buildings, fuel, flumes, shafts, and drifts. They hauled in machinery to construct quartz mills and formed express companies to bring in supplies.

|

| Decaying mine remains are scattered today over the mountain slopes of Nevada's Comstock Lode, within sight of the Sierra. |

Nevada miners were responsible for significant advances in engineering techniques. Early mining at the Comstock Lode was close to the surface, quartz being collected from open or shallow shafts and horizontal tunnels. Philip Deidesheimer, a German engineer, originated a process that made possible the mining of quartz lodes at greater width and depth. The Deidesheimer system, used throughout the Comstock, attracted the attention of European mining engineers.

Until 1873 small companies worked the lode. Then the Consolidated Virginia Company, boring straight through the flinty mountain rock, struck a lode 54 feet wide and filled with both gold and silver—the Big Bonanza, probably the richest single find in mining history. Big companies gained the ascendancy.

Until 1880 the two prime characteristics of mining in Nevada, especially in the Comstock Lode area, were wildcat speculation and expensive litigation. In this atmosphere of frantic financial manipulation and unscrupulous rigging of the market, the "Kings of the Comstock" struggled for power, bought and sold seats in the U.S. Senate, and brought ruin to the Bank of California. Speculative investment in San Francisco reached a new high. As the hectic trading continued without any regulation, the wildly fluctuating market resulted in the rise and fall of many fortunes. But the Comstock Lode was not inexhaustible. In 1875 Nevada's mining stocks had a value of $300 million; 5 years later less than $7 million. Thereafter mining was lethargic until the Tonopah rush in 1900.

But the effects of the Comstock Lode on the monetary world were permanent. The lode poured wealth into San Francisco and resulted in the establishment of a stock exchange, as well as the launching of the careers of a group of silver kings, which included James G. Fair, John W. Mackay, James C. Flood, and William S. O'Brien. The output of the Nevada mines strengthened the credit of the United States during the crucial years of the Civil War, stimulated freighting, and accelerated construction of the transcontinental railroad and helped determine its route. The effects were also international. The alteration in the ratio of gold and silver probably contributed to the demonetization of silver by European nations.

MONTANA—LAST CHANCE GULCH AND THE COPPER KINGS

The first prospectors in present Montana crossed the Continental Divide from the Idaho country and worked the headwaters of the Missouri River. In 1862 Granville Stuart, who later became an influential Montana rancher and whose father had been a forty niner, struck minor deposits of gold. When Colorado miners learned the news, a small rush to Montana ensued. Large parties of ex-Colorado miners, bound for the Salmon River area of Idaho, hearing of the discovery, changed their plans and prospected along the Beaverhead River in Montana. William Eads and John White made the first substantial gold discovery in Montana in 1862 on Grasshopper Creek, a tributary of the Beaverhead. Soon 500 miners rushed to the site and set up a mining camp they called Bannack. The following spring prospectors made another and richer strike 70 miles to the east at Alder Gulch. There Virginia City sprang up. The gulch yielded $30 million in gold during the next 3 years.

The rush to Montana country in 1863, following the glowing reports from Bannack and Virginia City, was of the usual sensational proportions. The Snake River camps in Idaho were declining, and prospectors joined others who trekked to Montana across the mountains and deserts from California, Oregon, and Colorado. Before long Montana, which 3 years earlier had been uninhabited by white men, had a population of 30,000.

|

| Pioneer City, first gold camp in Montana Territory, was almost a ghost town by 1883. Like other mining boomtowns, many of which were abandoned as rapidly as they were founded, its glory faded after the nuggets were gone. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

The miners' appetites for gold were whetted in 1864, when an ex-Georgia prospector named John Cowan, who was fruitlessly panning his way down the Missouri, decided to make one more attempt at a spot he called Last Chance Gulch. The result is history—and legend. In a few months Helena was founded on the site. Nearby were a dozen gulches containing rich gold deposits. The town was strategically located on the wagon route from Fort Benton to Bannack and Virginia City. Rapidly achieving a position of eminence, it became one of the most important cities of the mining era.

Mining in Montana entered a new phase in 1874, when an Idaho miner discovered silver at Butte. Here lay one of the world's richest mineral deposits—an area less than 5 miles square that eventually produced between $2 and $3 billion in mineral wealth. Butte prospered initially on the basis of its silver lodes, but along with the rest of Montana it was not on a healthy economic basis. The mines were scattered, transportation was poor, and many of the miners were leaving the region to join the rush to the Black Hills.

The strike of an Irish-born opportunist, Marcus Daly, precipitated the greatest phase of Montana's mining history—the copper era. In 1881 Daly persuaded capitalists to invest in his Anaconda Mine at Butte and began digging for silver. Disappointed when his shaft struck copper instead of silver, he persisted in his effort to locate a silver vein and finally, in 1883, struck a copper vein 50 feet wide and of unparalleled richness. Butte gained an international reputation as the "richest hill on earth." In addition to attracting miners from throughout the West, the high wages paid for labor brought workers from Ireland, England, Wales, Germany, and Italy.

Wars ensued between the copper kings of Butte similar to those between gold and silver kings elsewhere. Extreme wealth induced a frenzied struggle for even more wealth and political power. The accomplishments of Daly, who became the head of one of the world's most powerful monopolies, were similar to those of other noted benefactors who amassed fortunes from the mines. Daly was a founder and builder of cities. He mined coal for his furnaces, and acquired huge tracts of timber to supply lumber for his mines; he established banks, powerplants, and irrigation systems. And he was a force in Montana politics. His final achievement was combining a series of lumber and mining companies into an industrial giant called the Amalgamated Copper Company.

The wars between the copper kings alternated with labor battles. The men who worked the mines of Butte were also influential in State politics. As the city rose quickly to the position of the world's copper metropolis, a strong movement developed among the miners for organization. This culminated in 1893 in the founding of the militant Western Federation of Miners. Perhaps to a greater degree than in any other State, the mining industry of Montana, centered at Butte, influenced directly or indirectly every major industry in the State.

IDAHO—WEALTH IN THE WILDERNESS

Another source of mineral wealth was the Idaho region, which became a Territory in 1863 and was admitted to the Union as a State in 1890. Late in 1859 an Indian trader, Capt. Elias D. Pierce, while prospecting in Nez Perce country along the Clearwater River just north of the old Oregon Trail, discovered gold. Soon reports of the find reached Portland. Miners from the region flocked to the diggings, despite some hostility on the part of the Nez Perces, and the mining camps of Pierce, Oro Fino, Elk City, and Florence sprang up. As the rush gained momentum, steamers began service up the Columbia and Snake Rivers from Portland to Lewiston, which developed into the principal distributing center for the region.

The miners next made strikes along the Salmon River and in mid-1862 discovered rich placer deposits in the Boise River Basin of southwestern Idaho. Within 2 years more than 15,000 people were residing in the latter district. And the next year prospectors found silver on the Owyhee River around Silver City.

|

| Placer mining in the Coeur d'Alene country of Idaho Territory, 1884. Miners directed a stream of water through the "Long Tom," then shoveled in raw earth. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

Reaching the rugged Idaho wilderness was a formidable chore, even for hardy Western prospectors. They came up the Missouri to Fort Benton, or they steamed up the Columbia to Lewiston or Walla Walla. The Mullan Road, constructed between 1859 and 1862 as a military road between Forts Benton and Walla Walla, eased the problem of transporting mining supplies and helped open the entire region to settlement. To safeguard the miners from the hostile Indians of that region, the U.S. Army built Fort Lapwai near Lewiston and Fort Boise near Boise.

Mining in Idaho had a renaissance late in the century. In 1885 Noah S. Kellogg was chasing after a runaway mule in the Coeur d'Alene district of Idaho. Pausing to rest, he looked down and discovered that he was sitting on a chunk of almost pure silver. By 1905 the mine had yielded $250 million and created more than 50 millionaires. The workers who came to operate the mills and mines provided the region with a permanent population.

Violence between miners' unions and the mineowners, not restricted to the Coeur d'Alene district, broke out there in 1892 when the union dynamited the mines in retaliation for the importation of strikebreakers. Another dynamiting in 1899 caused Gov. Frank Steunenberg to declare a state of insurrection and to obtain Federal troops from President McKinley. More than a thousand miners were arrested and the unions almost destroyed. But despite the labor turmoil the wealth of the mines at Coeur d'Alene and Kellogg transformed the region.

OREGON AND WASHINGTON—MINERS AND THE INDIAN THREAT

Although less spectacular than the earlier strikes in the West, those in Oregon and Washington attracted many miners. During the California rush, numerous Oregonians had joined the forty-niners, and many of them returned later with capital to develop the resources of their area. In the early 1850's prospectors began searching just across the California border, in southwestern Oregon Territory, but for a time irate Indians constituted a danger. Nevertheless in 1851 a strike was made at a site first known as Sailors' Diggings and later as Waldo. Successive strikes occurred in Jackson and Josephine Counties. The district flourished, and Jacksonville became the trading center. In 1861 miners opened the eastern Oregon mining district, in the vicinity of the Blue and Wallowa Mountains, and prospectors continued to make discoveries there in the 1870's and 1880's. Most of the mines in Oregon were comparatively small, and the rushes were modest in size—as were the returns.

In present Washington a strike was made in 1855 near Fort Colvile, on the east bank of the Columbia. But conflicts with the Indians were frequent, and most of the region was unsafe for prospectors for at least 3 years. When peace was finally restored, gold seekers thoroughly searched the area. They found little to repay them for their efforts.

Mining activity increased elsewhere in Washington during the 1880's as prospectors turned their attention from placer to lode mining. They discovered silver deposits in the Colville Mountains and along Salmon Creek and founded the Ruby Mining District. The discoveries in Washington and nearby Idaho caused Spokane to prosper and to become the metropolis of the "inland empire" of the Northwest.

UTAH—GOLD AND BINGHAM CANYON

Agriculture in Utah Territory had early profited from the mining booms of the West, especially that in California, but little mineral wealth had been found there. Then in 1862 Col. Patrick E. Connor assumed command of the District of Utah. Convinced that the Mormons were disloyal, he thought, that a mining rush would increase the non-Mormon population. In 1863, after soldiers and prospectors had discovered deposits of silver, lead, and copper in Bingham Canyon, Connor published a newspaper, the Union Vidette, which announced to one and all that the mountains were rich in minerals. He offered Government protection to parties of prospectors.

Under such a stimulus a rush started, a number of other strikes were made, and several mining camps arose. The town of Alta, in Little Cottonwood Canyon, gained almost as much fame from its Bucket of Blood and Gold Miner's Daughter saloons as from its Emma Mine.

Only a few Mormons joined the scramble to the diggings, for Brigham Young denounced the quest for easy wealth. Yet precious metals were not discovered in amounts sufficient to attract into Utah the huge non-Mormon population hoped for by Colonel Connor. Mining operations did not seriously interfere with Mormon affairs.

Unknown to the prospectors who were combing the Territory, however, the very mountain they raked for gold and silver at Bingham Canyon contained one of the largest copper deposits in the world—a major industry in 20th-century Utah.

NEW MEXICO—"LOST" MINES AND ISOLATION

New Mexico never experienced the prosperity of other mining areas. Small-scale mining there, however, long antedated its acquisition by the United States, in 1848. The Indians, Spaniards, and Mexicans worked the copper mines at Santa Rita, gold placers in the Ortiz and San Pedro Mountains, and various other deposits.

In 1860 some Americans, pursuing the ever-present rumors of "lost" mines, discovered gold placers at Pinos Altos, just north of Santa Rita. Below the placer deposits they found gold-bearing quartz veins, and numerous miners from California, Texas, Missouri, and Mexico rushed in. In 1861, however, Apaches forced the miners to abandon the site. Mining nearly ceased in New Mexico Territory during the Civil War, and for some time after the war transportation problems and the Indian hazard had an inhibiting effect. A silver boom occurred in the late 1870's, when several mining towns sprang up in the southern hills.

|

| Prospectors at work in the Cerrillos Mountains of New Mexico Territory in the 1880's. From a Henry Brown stereopticon. (Courtesy, Museum of New Mexico.) |

Isolation, the Apache danger, the lack of water, the predominance of base metals unsuited to simple milling, and the failure of prospectors to make any big strikes precluded any extensive mining in New Mexico until the 20th century, when uranium, oil, and natural gas became major sources of income.

WYOMING—LESSER STRIKES

Wyoming was another region where a major boom did not occur, though prospectors made a few small strikes. In the early 1860's they discovered gold in the Big Horn country, and for a few years this region attracted some miners from Montana. In 1867 a rush to the Sweetwater River region occurred, during which South Pass City and Atlantic City were founded. The boom ended quickly, however, for the pockets proved shallow. By 1870 the miners had left the Territory. Some prospecting continued during the 1870's and 1880's, but the people of Wyoming had long since turned their attention to the cattle industry.

THE BLACK HILLS—OPENING THE SIOUX COUNTRY

By the early 1870's only one region of the West had escaped the prospector's pick—the Black Hills of Dakota, a region occupied by the Sioux Indians and guarded by troops who barred all white men from the area. Tales were recounted of Indians who came from the Black Hills to Fort Laramie with nuggets of pure gold; of military commanders who suppressed news of gold discoveries to prevent wholesale desertions; and of Father De Smet, the pioneer Jesuit missionary who had obtained gold from the Indians before the discovery in California and warned them not to reveal this secret if they wished to retain their hunting grounds.

In 1867 more substantial proof of the riches of the Black Hills was forthcoming. A report concerning the mineral resources east of the Rocky Mountains, drawn up at the order of the Secretary of the Treasury, was published. Asserting that explorations by Lt. G. K. Warren in 1857 and Capt. W. F. Raynolds in 1859 and 1860 had verified that the Black Hills were rich in gold and silver, as well as iron, coal, and copper, it stated: "With the pacification of the Sioux Indians and the establishment of emigrant roads, this district of Dakota would doubtless be the scene of great mining excitement, as the goldfield of the Black Hills is accessible at a distance of 120 miles from the Missouri River."

|

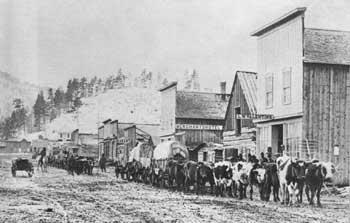

| Bull freighters arriving in Crook City, Black Hills, 1877. Pierre, Dakota Territory, was the Missouri River port of entry for the Black Hills mining region. Freighters also operated from Bismarck and other Missouri River points to interior settlements. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

By the early 1870's, when the mines of the West were passing from the hands of the prospectors to those of Eastern capitalists, increasing pressures were brought to bear on the Government to open the Black Hills to prospecting. More and more gold seekers began congregating just outside the forbidden area. Alarmed at this buildup, the Government in 1874 organized a military expedition under Gen. George A. Custer, accompanied by a group of scientists, to explore the mineral resources of the region. Custer reported that gold was present in the Black Hills in profitable amounts.

|

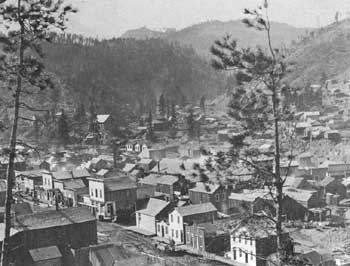

| Deadwood Gulch, South Dakota Territory, in 1877. One of the last great mining strikes was made at Deadwood, whose name is synonymous with "Wild Bill" Hickok and Calamity Jane. Many buildings from the town's heyday have survived. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

The news caused gold seekers from all over the West to jam into adjacent towns, such as Bismarck, Cheyenne, and Sioux City, and loudly demand that the region be opened to miners. Many clandestinely slipped into the Black Hills, and the Army kept busy ejecting them. In 1875, after a special commission failed to obtain any concessions from the Indians, the Government, foreseeing the inevitable and unable to control the situation indefinitely, threw open the Black Hills to anyone who was willing to accept the risks involved. Nearly 15,000 miners entered the region in the next few months. They provided one of the causes of the Sioux uprising in 1876, highlighted by the annihilation of Custer's force at the Little Bighorn. In 1877 the Sioux were forced to cede the Black Hills.

|

| Wells-Fargo guards escort a gold shipment out of Deadwood, Dakota Territory. Photograph by John C. H. Grabill. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) |

The objective of the first group of prospectors in the Black Hills was French Creek, where they laid out Custer City. Then in the fall of 1875 a party of gold seekers made one of the last great strikes of the mining frontier at Deadwood Gulch. The town that grew up nearby took its name from the gulch and there they mining frontier reached its zenith. It was as wild as any in the West. The placers at Deadwood, and nearby Lead, brought fortunes to many prospectors. But the surface deposits were quickly exhausted. To extract precious metal from the quartz, heavily capitalized companies, such as the Homestake, took over, and the colorful, highly individualistic era of the prospector and placer miner came to an end in the Black Hills. With the Deadwood boom, the eastward movement of the mining frontier ended.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/prospector-cowhand-sodbuster/intro2.htm

Last Updated: 22-May-2005