|

THE BOOK OF THE NATIONAL PARKS

|

THE VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARKS

XI

THREE MONSTERS OF HAWAII

HAWAII NATIONAL PARK, HAWAIIAN ISLANDS. AREA, 118 SQUARE MILES

IF this chapter is confined to the three volcano tops which Congress reserved on the islands of Hawaii and Maui in 1917, wonderful though these are, it will describe a small part indeed of the wide range of novelty, charm, and beauty which will fall to the lot of those who visit the Hawaii National Park. One of the great advantages enjoyed by this national park, as indeed by Mount McKinley's, is its location in a surrounding of entire novelty, so that in addition to the object of his visit, itself so supremely worth while, the traveller has also the pleasure of a trip abroad.

In novelty at least the Hawaii National Park has the advantage over the Alaskan park because it involves the life and scenery of the tropics. We can find snow-crowned mountains and winding glaciers at home, but not equatorial jungles, sandalwood groves, and surf-riding.

Enormous as this element of charm unquestionably is, this is not the place to sing the pleasures of the Hawaiian Islands. Their palm-fringed horizons, surf-edged coral reefs, tropical forests and gardens, plantations of pineapple and sugar-cane are as celebrated as their rainbows, earthquakes, and graceful girls dancing under tropical stars to the languorous ukelele.

|

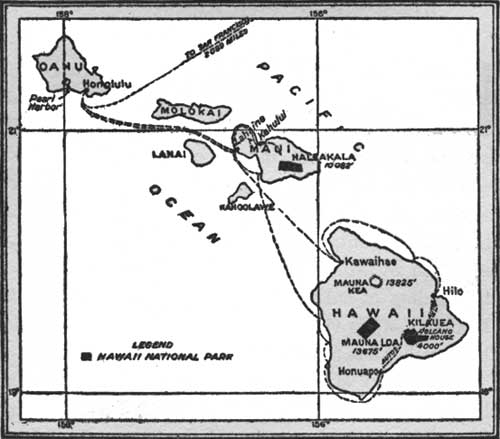

| MAP OF HAWAII NATIONAL PARK |

Leaving these and kindred spectacles to the steamship circulars and the library shelf, it is our part to note that the Hawaii National Park possesses the fourth largest volcanic crater in the world, whose aspect at sunrise is one of the world's famous spectacles, the largest active volcano in the world, and a lake of turbulent, glowing, molten lava, "the House of Everlasting Fire," which fills the beholder with awe.

It was not at all, then, the gentle poetic aspects of the Hawaiian Islands which led Congress to create a national park there, though these form its romantic, contrasted setting. It was the extraordinary volcanic exhibit, that combination of thrilling spectacles of Nature's colossal power which for years have drawn travellers from the four quarters of the earth. The Hawaii National Park includes the summits of Haleakala, on the island of Maui, and Mauna Loa and Kilauea, on the island of Hawaii.

Spain claims the discovery of these delectable isles by Juan Gaetano, in 1555, but their formal discovery and exploration fell to the lot of Captain James Cook, in 1778. The Hawaiians thought him a god and loaded him with the treasures of the islands, but on his return the following year his illness and the conduct of his crew ashore disillusioned them; they killed him and burned his flesh, but their priests deified his bones, nevertheless. Parts of these were recovered later and a monument was erected over them. Then civil wars raged until all the tribes were conquered, at the end of the eighteenth century, by one chieftain, Kamehameha, who became king. His descendants reigned until 1874 when, the old royal line dying out, Kalakaua was elected his successor.

From this time the end hastened. A treaty with the United States ceded Pearl Harbor as a coaling-station and entered American goods free of duty, in return for which Hawaiian sugar and a few other products entered the United States free. This established the sugar industry on a large and permanent scale and brought laborers from China, Japan, the Azores, and Madeira. More than ten thousand Portuguese migrated to the islands, and the native population began a comparative decrease which still continues.

After Kalakaua's death, his sister Liliuokalani succeeding him in 1891, the drift to the United States became rapid. When President Cleveland refused to annex the islands, a republic was formed in 1894, but the danger from Japanese immigration became so imminent that in 1898, during the Spanish-American War, President McKinley yielded to the Hawaiian request and the islands were annexed to the United States by resolution of Congress.

The setting for the picture of our island-park will be complete with several facts about its physical origin. The Hawaiian Islands rose from the sea in a series of volcanic eruptions. Originally, doubtless, the greater islands were simple cones emitting lava, ash, and smoke, which coral growths afterward enlarged and enriched. Kauai was the first to develop habitable conditions, and the island southeast of it followed in order. Eight of the twelve are now habitable.

The most eastern island of the group is Hawaii. It is also much the largest. This has three volcanoes. Mauna Loa, greatest of the three, and also the greatest volcanic mass in the world, is nearly the centre of the island; Kilauea lies a few miles east of it; the summits of both are included in the national park. Mauna Kea, a volcanic cone of great beauty in the north centre of the island, forming a triangle with the other two, is not a part of the national park.

Northwest of Hawaii across sixty miles or more of salt water is the island of Maui, second largest of the group. In its southern part rises the distinguished volcano of Haleakala, whose summit and world-famous crater is the third member of the national park. The other habited islands, in order westward, are Kahoolawe, Lanai, Molokai, Oahu, Kauai, and Niihau; no portions of these are included in the park. Kahoolawe, Lanai, and Niihau are much the smallest of the group.

HALEAKALA

Of the three volcanic summits which concern us, Haleakala is nearest the principal port of Honolulu, though not always the first visited. Its slopes nearly fill the southern half of the island of Maui.

The popular translation of the name Haleakala is "The House of the Sun"; literally the word means "The House Built by the Sun." The volcano is a monster of more than ten thousand feet, which bears upon its summit a crater of a size and beauty that make it one of the world's show-places. This crater is seven and a half miles long by two and a third miles wide. Only three known craters exceed Haleakala's in size. Asosan, the monster crater of Japan, largest by far in the world, is fourteen miles long by ten wide and contains many farms. Lago di Bolseno, in Italy, next in size, measures eight and a half by seven and a half miles; and Monte Albano, also in Italy, eight by seven miles.

Exchanging your automobile for a saddle-horse at the volcano's foot, you spend the afternoon in the ascent. Wonderful indeed, looking back, is the growing arc of plantation and sea, islands growing upon the horizon, Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa lifting distant snow-tipped peaks. You spend the night in a rest house on the rim of the crater, but not until you have seen the spectacle of sunset; and in the gray of the morning you are summoned to the supreme spectacle of sunrise. Thousands have crossed seas for Haleakala's sunrise.

That first view of the crater from the rim is one never to be forgotten. Its floor lies two thousand feet below, an enormous rainless, rolling plain from which rise thirteen volcanic cones, clean-cut, as regular in form as carven things. Several of these are seven hundred feet in height. "It must have been awe-inspiring," writes Castle, "when its cones were spouting fire, and rivers of scarlet molten lava crawled along the floor."

The stillness of this spot emphasizes its emotional effect. A word spoken ordinarily loud is like a shout. You can hear the footsteps of the goats far down upon the crater floor. Upon this floor grow plants known nowhere else; they are famous under the name of Silver Swords—yucca-like growths three or four feet high whose drooping filaments of bloom gleam like polished silver stilettos.

When Mark Twain saw the crater, "vagrant white clouds came drifting along, high over the sea and valley; then they came in couples and groups; then in imposing squadrons; gradually joining their forces, they banked themselves solidly together a thousand feet under us and totally shut out land and ocean; not a vestige of anything was left in view, but just a little of the rim of the crater circling away from the pinnacle whereon we sat, for a ghostly procession of wanderers from the filmy hosts without had drifted through a chasm in the crater wall and filed round and round, and gathered and sunk and blended together till the abyss was stored to the brim with a fleecy fog. Thus banked, motion ceased, and silence reigned. Clear to the horizon, league on league, the snowy folds, with shallow creases between, and with here and there stately piles of vapory architecture lifting themselves aloft out of the common plain—some near at hand, some in the middle distances, and others relieving the monotony of the remote solitudes. There was little conversation, for the impressive scene overawed speech. I felt like the Last Man, neglected of the judgment, and left pinnacled in mid-heaven, a forgotten relic of a vanished world."

The extraordinary perfection of this desert crater is probably due to two causes. Vents which trapped it far down the volcano's flanks prevented its filling with molten lava; absence of rain has preserved its walls intact and saved its pristine beauty from the defacement of erosion.

Haleakala has its legend, and this Jack London has sifted to its elements and given us in "The Cruise of the Snark." I quote:

"It is told that long ago, one Maui, the son of Hina, lived on what is now known as West Maui. His mother, Hina, employed her time in the making of kapas. She must have made them at night, for her days were occupied in trying to dry the kapas. Each morning, and all morning, she toiled at spreading them out in the sun. But no sooner were they out than she began taking them in in order to have them all under shelter for the night. For know that the days were shorter then than now. Maui watched his mother's futile toil and felt sorry for her. He decided to do something—oh, no, not to help her hang out and take in the kapas. He was too clever for that. His idea was to make the sun go slower. Perhaps he was the first Hawaiian astronomer. At any rate, he took a series of observations of the sun from various parts of the island. His conclusion was that the sun's path was directly across Haleakala. Unlike Joshua, he stood in no need of divine assistance. He gathered a huge quantity of cocoanuts, from the fibre of which he braided a stout cord, and in one end of which he made a noose, even as the cowboys of Haleakala do to this day.

"Next he climbed into the House of the Sun. When the sun came tearing along the path, bent on completing its journey in the shortest time possible, the valiant youth threw his lariat around one of the sun's largest and strongest beams. He made the sun slow down some; also, he broke the beam short off. And he kept on roping and breaking off beams till the sun said it was willing to listen to reason. Maui set forth his terms of peace, which the sun accepted, agreeing to go more slowly thereafter. Wherefore Hina had ample time in which to dry her kapas, and the days are longer than they used to be, which last is quite in accord with the teachings of modern astronomy."

MAUNA LOA

Sixty miles south of Maui, Hawaii, largest of the island group, contains the two remaining parts of our national park. From every point of view Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, both snow-crowned monsters approaching fourteen thousand feet of altitude, dominate the island. But Mauna Kea is not a part of the national park; Kilauea, of less than a third its height, shares that honor with Mauna Loa. Of the two, Kilauea is much the older, and doubtless was a conspicuous figure in the old landscape. It has been largely absorbed in the immense swelling bulk of Mauna Loa, which, springing later from the island soil near by, no doubt diverting Kilauea's vents far below sea-level, has sprawled over many miles. So nearly has the younger absorbed the older, that Kilauea's famous pit of molten lava seems almost to lie upon Mauna Loa's slope.

|

|

THE KILAUEA PIT OF FIRE, HAWAII NATIONAL PARK Photographed at night by the light of its flaming lavas From a photograph copyright by E. M. Newman |

|

|

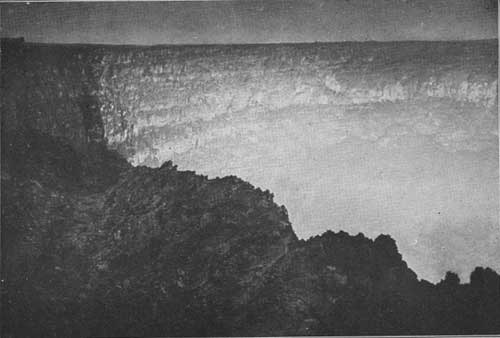

WITHIN THE CRATER OF KILAUEA From a photograph copyright by Newman Travel Talks and Brown and Dawson |

Mauna Loa soars 13,675 feet. Its snowy dome shares with Mauna Kea, which rises even higher, the summit honors of the islands. From Hilo, the principal port of the island of Hawaii, Mauna Loa suggests the back of a leviathan, its body hidden in the mists. The way up, through forests of ancient mahogany and tangles of giant tree-fern, then up many miles of lava slopes, is one of the inspiring tours in the mountain world. The summit crater, Mokuaweoweo, three-quarters of a mile long by a quarter mile wide, is as spectacular in action as that of Kilauea.

This enormous volcanic mass has grown of its own output in comparatively a short time. For many decades it has been extraordinarily frequent in eruption. Every five or ten years it gets into action with violence, sometimes at the summit, oftener of recent years since the central vent has lengthened, at weakened places on its sides. Few volcanoes have been so regularly and systematically studied.

KILAUEA

The most spectacular exhibit of the Hawaii National Park is the lake of fire in the crater of Kilauea.

Kilauea is unusual among volcanoes. It follows few of the popular conceptions. Older than the towering Mauna Loa, its height is only four thousand feet. Its lavas have found vents through its flanks, which they have broadened and flattened. Doubtless its own lavas have helped Mauna Loa's to merge the two mountains into one. It is no longer explosive like the usual volcano; since 1790, when it destroyed a native army, it has ejected neither rocks nor ashes. Its crater is no longer definitely bowl-shaped. From the middle of a broad flat plain, which really is what is left of the ancient great crater, drops a pit with vertical sides within which boil its lavas.

The pit, the lake of fire, is Halemaumau, commonly translated "The House of Everlasting Fire"; the correct translation is "The House of the Maumau Fern," whose leaf is twisted and contorted like some forms of lava. Two miles and a little more from Halemaumau, on a part of the ancient crater wall, stands the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, which is under the control of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The observatory was built for the special purpose of studying the pit of fire, the risings and fallings of whose lavas bear a relationship toward the volcanism of Mauna Loa which is scientifically important, but which we need not discuss here.

The traveller enters Hawaii by steamer through Hilo. He reaches the rim of Kilauea by automobile, an inspiring run of thirty-one miles over a road of volcanic glass, bordered with vegetation strange to eyes accustomed only to that of the temperate zone—brilliant hibiscus, native hardwood trees with feathery pompons for blossoms, and the giant ferns which tower overhead. On the rim are the hotels and the observatory. Steam-jets emerge at intervals, and hot sulphur banks exhibit rich yellows. From there the way descends to the floor of the crater and unrolls a ribbon of flower-bordered road seven miles long to the pit of fire. By trail, the distance is only two miles and a half across long stretches of hard lava congealed in ropes and ripples and strange contortions. Where else is a spectacle one-tenth as appalling so comfortably and quickly reached?

Halemaumau is an irregular pit a thousand feet long with perpendicular sides. Its depth varies. Sometimes one looks hundreds of feet down to the boiling surface; sometimes its lavas overrun the top. The fumes of sulphur are very strong, with the wind in your face. At these times, too, the air is extremely hot. There are cracks in the surrounding lava where you can scorch paper or cook a beefsteak.

Many have been the attempts to describe it. Not having seen it myself, I quote two here; one a careful picture by a close student of the spectacle, Mr. William R. Castle, Jr., of Honolulu; the other a rapid sketch by Mark Twain.

"By daylight," writes Castle, "the lake of fire is a greenish-yellow, cut with ragged cracks of red that look like pale streaks of stationary lightning across its surface. It is restless, breathing rapidly, bubbling up at one point and sinking down in another; throwing up sudden fountains of scarlet molten lava that play a few minutes and subside, leaving shimmering mounds which gradually settle to the level surface of the lake, turning brown and yellow as they sink.

"But as the daylight fades the fires of the pit shine more brightly. Mauna Loa, behind, becomes a pale, gray-blue, insubstantial dome, and overhead stars begin to appear. As darkness comes the colors on the lake grow so intense that they almost hurt. The fire is not only red; it is blue and purple and orange and green. Blue flames shimmer and dart about the edges of the pit, back and forth across the surface of the restless mass. Sudden fountains paint blood-red the great plume of sulphur smoke that rises constantly, to drift away across the poisoned desert of Kau. Sometimes the spurts of lava are so violent, so exaggerated by the night, that one draws back terrified lest some atom of their molten substance should spatter over the edge of the precipice. Sometimes the whole lake is in motion. Waves of fire toss and battle with each other and dash in clouds of bright vermilion spray against the black sides of the pit. Sometimes one of these sides falls in with a roar that echoes back and forth, and mighty rocks are swallowed in the liquid mass of fire that closes over them in a whirlpool, like water over a sinking ship.

"Again everything is quiet, a thick scum forms over the surface of the lake, dead, like the scum on the surface of a lonely forest pool. Then it shivers. Flashes of fire dart from side to side. The centre bursts open and a huge fountain of lava twenty feet thick and fifty high, streams into the air and plays for several minutes, waves of blinding fire flowing out from it, dashing against the sides until the black rocks are starred all over with bits of scarlet. To the spectator there is, through it all, no sense of fear. So intense, so tremendous is the spectacle that silly little human feelings find no place. All sensations are submerged in a sense of awe."

Mark Twain gazed into Halemaumau's terrifying depths. "It looked," he writes, "like a colossal railroad-map of the State of Massachusetts done in chain lightning on a midnight sky. Imagine it—imagine a coal-black sky shivered into a tangled network of angry fire!

"Here and there were gleaming holes a hundred feet in diameter, broken in the dark crust, and in them the melted lava—the color a dazzling white just tinged with yellow—was boiling and surging furiously; and from these holes branched numberless bright torrents in many directions, like the spokes of a wheel, and kept a tolerably straight course for a while and then swept round in huge rainbow curves, or made a long succession of sharp worm-fence angles, which looked precisely like the fiercest jagged lightning. Those streams met other streams, and they mingled with and crossed and recrossed each other in every conceivable direction, like skate-tracks on a popular skating-ground. Sometimes streams twenty or thirty feet wide flowed from the holes to some distance without dividing—and through the opera-glasses we could see that they ran down small, steep hills and were genuine cataracts of fire, white at their source, but soon cooling and turning to the richest red, grained with alternate lines of black and gold. Every now and then masses of the dark crust broke away and floated slowly down these streams like rafts down a river.

"Occasionally, the molten lava flowing under the superincumbent crust broke through—split a dazzling streak, from five hundred to a thousand feet long, like a sudden flash of lightning, and then acre after acre of the cold lava parted into fragments, turned up edge-wise like cakes of ice when a great river breaks up, plunged downward, and were swallowed in the crimson caldron. Then the wide expanse of the 'thaw' maintained a ruddy glow for a while, but shortly cooled and became black and level again. During a 'thaw' every dismembered cake was marked by a glittering white border which was superbly shaded inward by aurora borealis rays, which were a flaming yellow where they joined the white border, and from thence toward their points tapered into glowing crimson, then into a rich, pale carmine, and finally into a faint blush that held its own a moment and then dimmed and turned black. Some of the streams preferred to mingle together in a tangle of fantastic circles, and then they looked something like the confusion of ropes one sees on a ship's deck when she has just taken in sail and dropped anchor—provided one can imagine those ropes on fire.

"Through the glasses, the little fountains scattered about looked very beautiful. They boiled, and coughed, and spluttered, and discharged sprays of stringy red fire—of about the consistency of mush, for instance—from ten to fifteen feet into the air, along with a shower of brilliant white sparks—a quaint and unnatural mingling of gouts of blood and snowflakes."

One can descend the sides and approach surprisingly close to the flaming surface, the temperature of which, by the way, is 1750 degrees Fahrenheit.

Such is "The House of Everlasting Fire" to-day. But who can say what it will be a year or a decade hence? A clogging or a shifting of the vents below sea-level, and Kilauea's lake of fire may become again explosive. Who will deny that Kilauea may not soar even above Mauna Loa? Stranger things have happened before this in the Islands of Surprise.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

yard3/chap11.htm

Last Updated: 30-Oct-2009