|

THE TOP OF THE CONTINENT

|

II

THE FIRST DITCH-DIGGERS

HOW THE GLACIERS HELPED MAKE THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK

THE Front Range of the Rocky Mountains was a delightful revelation to the women and the children of the Jefferson family, none of whom had seen mountains higher than the Catskills and the Adirondacks. Emerging, in an automobile stage, from a long and magnificent gorge through the foot-hills, they found themselves in a spacious rolling valley across whose farther horizon stretched a line of bold, purplish-gray, snow-topped mountains.

The valley was gloriously green. It was dotted with open meadows and forest patches. Graceful hills and fantastic rocky cliffs surrounded its nearer sides. Back of all, miles away, rising apparently perpendicularly from the luxuriant forest, stretched a grim background of high, snow-spattered mountains.

"Oh! Oh! Oh!" called Margaret in awed tones.

Jack stood up, shouting in his excitement. Mrs. Jefferson drew a long, quick breath; neither she nor Aunt Jane spoke. The young men were keenly interested and asked many questions of the driver. After a while, as they drew rapidly into the valley, the mountains looming higher and revealing themselves in full, Uncle Billy explained.

|

|

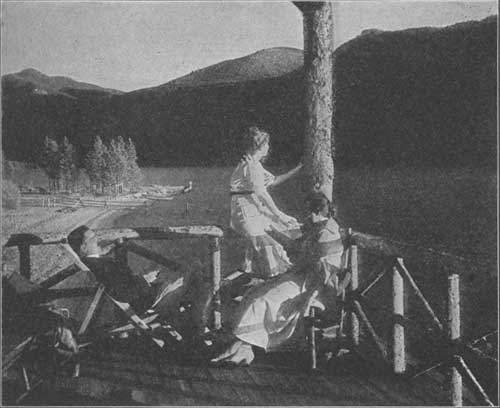

Sundown at Grand Lake Photograph by Wiswall Brothers |

"These are not at all like the mountains in Glacier National Park," he said. "You cannot imagine anything more different. These mountains loom more. They seem more jagged. They mass heavier. At the same time they are colored differently. They seem daintier somehow. They do not seem real to me."

"They are like a dream," said Aunt Jane quickly.

"It's more than that," cried Margaret. "It is like Fairyland."

"Same thing," said practical Jack. "Neither dreams nor fairies are real. But those mountains are real, all right. Oh, see that big bunch of them over on the left. Gee! I must climb to the tippy top of the biggest of them."

"The driver says that is the Longs Peak group," said Uncle Billy. "Longs Peak is the highest mountain of them all. It is 14,255 feet high. It can be climbed, but it is a long, hard day's work."

They swung past groups of small summer homes. A large showy hotel appeared on the right. Men and women were playing golf. Automobiles were frequently met. Many persons, singly and in parties, rode by on horseback.

"Almost everybody wears khaki suits just like mine," said Jack proudly.

"And oh," exclaimed Margaret, "there are ladies on horseback dressed just like men! They haven't any skirts at all. I don't think that is nice, do you, Aunt Jane?"

Aunt Jane flushed and said nothing.

"That's a good joke on you, Jane," laughed Mrs. Jefferson.

"What is a good joke on Aunt Jane?" demanded both children at once.

"Aunt Jane has no skirt to her new mountain riding-suit either," said Mother.

"Oh, Aunt Jane!" cried Margaret, shocked.

"You'll have to get used to that in the mountains," said Uncle Billy gayly. "Up here the ladies dress sensibly. Not only on horseback, but tramping on the trails, many women wear either very short skirts or no skirts at all."

"Circumstances alter cases, Margaret," explained Mother gently. "It is just as foolish for women to wear long skirts for mountain-climbing as it would be for bathing at Atlantic City."

They entered a straggling village of one street. Two-story shops, small frame hotels, and transportation offices lined both sides.

"What a funny little town!" said Margaret.

"This is the village of Estes Park," said Uncle Billy. "Here is where we change to our hotel bus. The hotels lie out in all directions for several miles."

"Why, I thought we were in the Rocky Mountain National Park," said Margaret, disappointed

"The boundary-line of the Rocky Mountain National Park lies just beyond the village," said Uncle Billy. "Most of the people stay down in this lovely valley and take trips into the mountains. There are hotels up there, too."

After lunch and another automobile ride, the Jeffersons were duly installed in a straggling rustic hotel. They occupied rooms in one of many log houses clustered around the main house, where they had their meals and sat evenings around the great open fireplace. They had all the comforts and most of the luxuries of the resort hotels in the East; but here, in these apparently rude surroundings, they enjoyed also a sense of sympathy with the wild mountains which rose directly behind them.

"See those funny little squirrels!" cried Margaret as soon as they were settled. "Oh, look at that one! He isn't a bit afraid. Oh, goodness, he's coming right at me."

Jack shouted with glee.

"Just like a girl!" he exclaimed. "It's you that's afraid, not he. Besides, they are not squirrels; they're chipmunks. They're awfully tame. I'm going to throw that one a peanut."

But even Jack was startled a minute later when one of the chipmunks scampered up on his lap and took a nut from his hand.

"Who's 'fraid now?" cried Margaret.

For a long while both children forgot the mountains in their interest in the chipmunks. Jack even persuaded one to climb to his shoulder and then to his head to receive a peanut.

"Aren't they greedy?" exclaimed Margaret. "I don't see how they can eat so many nuts."

"But they don't eat them," explained Mrs. Jefferson, who had been asking questions. "See, they poke them into pockets in their cheeks and every now and then run to their homes under ground and store them away for winter."

"Just like ants," said Margaret.

Their visit to the Rocky Mountain National Park was full of the most delightful surprises. The first was the effect of altitude, for the valley where most of the hotels are situated lies from seven to nine thousand feet above sea-level. The children found that running put them out of breath quickly and that the only way they could climb the still higher mountains was to move quite slowly and rest frequently. They were much puzzled at first.

"The air is thickest at sea-level," Uncle Tom explained, "and the higher you go up, the thinner it gets, until finally there isn't any air at all. So up here, where we live a mile and a half higher than we do at home, we draw less air into our lungs with each breath. Now, running and climbing uses up more air than sitting still, so we begin to pant more quickly here than at home. When you climb up those mountains you will find the air still thinner. You will have to move more slowly yet. But it won't hurt you to do that."

Climbing the mountain-trails on horseback was another pleasant surprise. Even the ladies found that they could ride the steep and rocky trails for hours a day without special weariness.

"Don't drive your horse," said the guide. "Hold the reins loosely, but let him take his own course and pick his way to suit himself. A mountain-trained horse has only two desires in life: one of these is to follow the horse ahead, the other is to get home for dinner. I will ride ahead and keep the trail; the other horses will follow if you will only let them alone."

"But suppose he gets dizzy and falls off the rocks," said Margaret nervously. "I would rather get off and walk."

|

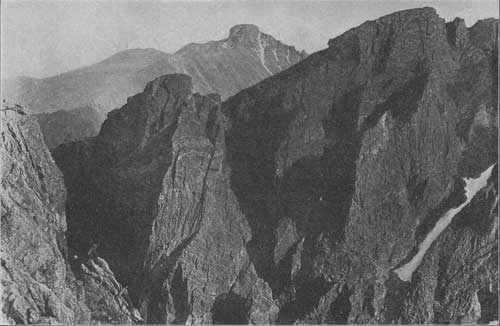

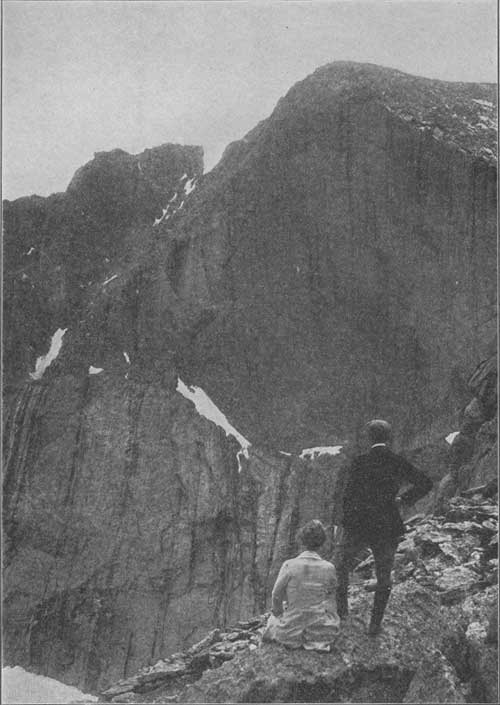

| The Heart of the Rockies. Longs Peak from Flattop Mountain Trail |

"He won't." said Uncle Billy. "A horse has no imagination. He cares for nothing but the trail, and he fears nothing. If you were to walk around some of these steep places, you would become afraid and that would be the surest way to fall off and bump your head. That is because you have imagination. Leave it to the horse and you'll be all right."

The ladies, who had feared that the trails would skirt the edges of great precipices, were pleasantly surprised to find that, even when they crossed the Continental Divide over Flattop Mountain, more than twelve thousand feet above sea-level, the trail lay always a safe distance back from dangerous edges.

They lunched on Flattop Mountain.

"Uncle Billy," said Jack in an awed voice, "isn't this the top of the continent?"

"It is pretty near it, Jack," said Uncle Billy. "You will not find many spots in this world wilder than this, I imagine. These rocks back of us look like pebbles when compared with those enormous granite cliffs over there, but they are fully as big as big churches, nevertheless."

"That one must be as big as the Philadelphia City Hall," said Jack.

"I think you are right. Perhaps it is even bigger. But, how little it seems when you compare it with the top of Hallett Peak, just across that chasm. Now, that chasm, Jack, must be two thousand feet deep—nearly half a mile."

|

| Uncle Billy washed Aunt Jane's face with a handful of snow |

"And that big snow-bank; doesn't it ever melt?" asked Jack.

"No" said Uncle Billy. "It is there always. In winter it is covered much deeper with fresh snow, and as warm weather comes along the fresh snow melts off. But that much lasts always. Let's snowball."

The children were delighted with the thought of snowballing in June, and after lunch was eaten and the paper boxes that contained it were carefully burned the whole party found a couple of acres of snow in which they frolicked till even Jack was tired out. Uncle Billy washed Aunt Jane's face with a handful of snow and made her cheeks rosier than ever. Jack heaped snow upon Uncle Billy till only his head and hands emerged. Even Mother took a hearty part in the fun.

"Why, see those hens," said Margaret on their way back to the horses. "There must be a farmhouse up here."

"They're bantams," cried Jack, "but they look more like partridges or pigeons. They're just as tame—why, you can almost catch them."

"They are not chickens," said the guide, laughing. "They are ptarmigan—wild birds that live only on the high mountains. In winter they turn perfectly white, just the color of the snow."

"How funny!" cried Margaret. "Why?"

"That is what is called protective coloring," explained Uncle Tom. "When all these mountains become snow-covered, the eagles and mountain-lions could see the ptarmigan a mile away if they should remain their present dark color. So nature gives them white feathers in snow time. Then they are reasonably safe.

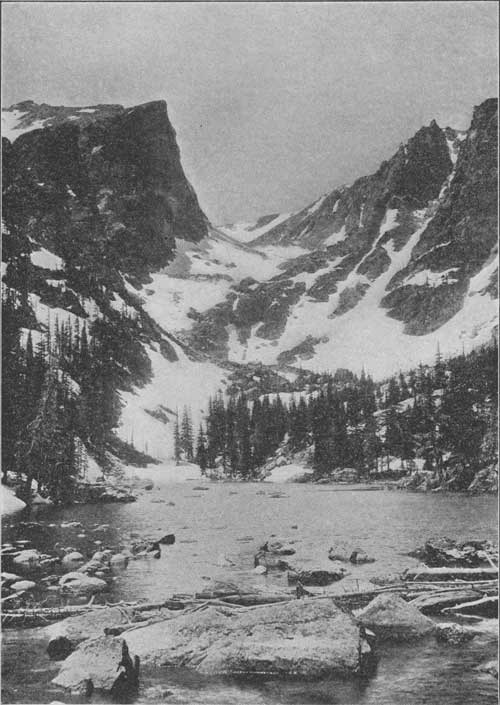

Another day they followed the beautiful Fall River Road to the end of Trail Ridge, and from there walked to Iceberg Lake. The view was just as fine as that from Flattop Mountain, but altogether different. They followed a trail a couple of miles along a bare lofty ridge twelve thousand five hundred feet high.

"Now," said the guide, "be careful. Take hold of my hands as we come to this precipice. It drops straight down nearly a thousand feet."

It was a timid party that approached the edge of the great precipice. A vast gulf, seemingly carved out of the solid granite, lay at their feet. Beyond it, far below, lay a superb pine-covered valley, and beyond that were other high mountains.

But the great gulf at their feet was what drew all eyes. It was semicircular in shape, and the cold granite walls were almost perpendicular. Gradually, holding hands, they advanced quite close to the edge and looked down into the depths. There they saw a lake of dark turquoise-blue on which floated large cakes of ice. Snow-banks touched the water in places at the edges. A stream ran out of the lower end and was lost in the splendid green valley. Two eagles circled in the depths below them.

They looked silently for a long time.

"It is like looking down a well," said Jack, "but I never saw a well so big as this. Uncle Tom, how did it come to be like this?"

"Here," said Uncle Tom, "you can read the story of the glaciers. This vast bowl of solid granite is called a cirque. It was carved out by the glacier which once lay within it. Originally the cirque was nothing but a depression in a granite slope. Ice settled in the depression and froze to its rocky sides. The weight of the snows lying upon this ice began to push it down-hill, and that motion made a glacier of it. When this glacier began to slip, it pulled away some of the rock to which its edges were frozen. That undermined the slope, and the rock above split off, fell, and left a perpendicular cliff. Then the glacier froze fast to the bottom of the cliff and undermined some more rock. Of course the rock above it split off again and fell, and that made the cliff higher. In that way the glacier worked back into the granite.

"But at the same time it was pulling away the rock frozen to its bottom, and that made the cirque deeper. So in a few million years it turned a slight hollow in a granite slope into this enormous well."

|

| A full-grown brown bear |

"All the rock which the glacier undermined and pulled away from the bottom, together with that which fell upon it from above, it carried away into that immense valley you see to the north, which is now called the Forest Canyon because of its beautiful forests. But then it was the bed of an enormous glacier of which this smaller glacier was a lesser tributary."

Not only the children but the ladies listened with intense interest.

"But what is a glacier?" asked Margaret.

"A river of ice," said Uncle Tom. "It begins in a cirque like this; just as a river of water begins in a spring or lake. This cirque is continually fed by the snows of winter; just as the spring or lake is fed by the rains. The glacier flows down through valleys; just as the river of water. It breaks into crevasses as it passes down the steep slants; just as the river of water breaks into ripples and rapids. It pours crashing over precipices in its course; just as the river of water pours over cliffs in waterfalls. Its surface rises and falls according to the snowfall of the winter before just as the river of water rises or falls according to the wetness or the dryness of the season. It sweeps up the rocks alongside its course and carries them downstream; just as the river of water sweeps up logs and branches from its banks."

"But there is one difference," said Aunt Jane, "the glacier does not run down to the sea and the river of water does."

"But the coast glacier does," said Uncle Tom. "In Alaska and other very cold areas glaciers sometimes run all the way to the ocean, and enormous pieces break off and float away. That is where the icebergs come from. But in inland regions like this, the glacier keeps flowing down to warmer levels until it comes to a place where ice melts. Then it turns into a river of water, which eventually finds its way to the sea. The end of a glacier is called its snout. Many of our great rivers begin at the snouts of glaciers."

"Oh!" said Margaret. "It's just like a fairy-story."

Jack said nothing, but he examined Iceberg Lake and the great cirque with deep attention.

Several days later as the party rode in automobiles in the valley near a village called Moraine Park, Jack asked:

"What a strange hill that is! It starts four or five miles back in the mountains and runs straight out into this big valley. Just look, Uncle Tom. It is the same height its whole length, and slopes off like a huge river-bank on both sides. Then it stops suddenly. Whatever made it like that?"

"That," said Uncle Tom, "is an extremely large moraine."

"What's a moraine?"

"Once," said Uncle Tom, "two huge converging glaciers flowed this way from the mountains, and joined just where that hill ends. Each followed a valley that a stream had previously made. Each deepened and rounded out its own valley and heaped upon the valley's sides great hills of broken rock and sand, most of which it had brought down from its mountain cirque. These hills of broken rock and sand are called moraines. You see them all through the Rocky Mountain National Park. They are really the banks of the great ice-rivers of the far distant past.

"Now, this particular moraine is so big because it lies just at the point where two specially large glaciers, after flowing several miles almost side by side, united into one. Both glaciers, you see, helped to build it. When these glaciers filled the valleys with their ice current, this great moraine between them must have looked like a tongue of land, ending in a point where the glaciers joined together."

During all the rest of their stay, the children kept a sharp lookout for moraines. The Rocky Mountain National Park has many moraines. The children found it great fun to trace the courses of these ancient ice rivers from their cirques under the precipices of the enormous Rockies far down into the valleys.

The Mills Moraine, which was built by a gigantic glacier which once flowed from Longs Peak, especially interested them because of the big turn it makes around the base of Mount Meeker.

"Why, the glacier that made the Mills Moraine must have been a mile thick," said Jack.

|

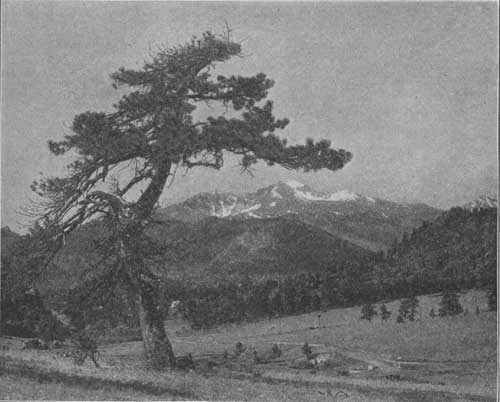

| Longs Peak (centre), Mount Meeker (left), and Mount Lady Washington |

"Hardly that," said Uncle Tom, "but it may have been nearly half a mile thick. See the moraine. It rises a thousand or more feet."

"I want to see where it started," said Jack.

And so came about their final adventure.

Meantime, they had explored the beaver-ponds and had seen Rocky Mountain sheep grazing on the slopes of Specimen Mountain. They had climbed to the top of the Twin Sisters and had seen the Forest Ranger searching the horizon for distant fires. They had fished in Bear Lake and had visited the wonderful wild flower gardens of Loch Vale. Longs Peak was reserved for the last.

"I cannot allow you children to go to the summit" said Mrs. Jefferson. "It may not be dangerous for men, and I know that many women climb it; but there are limits to everything, and that is where I draw the line."

Jack went into the woods to hide his disappointment, but Margaret wept aloud. Later they both admitted that Mother was right.

"Never mind, children," said Uncle Tom, "I will give up climbing to the summit. Instead, I will take you and Mother to see Chasm Lake, where that big glacier began that built up the Mills Moraine."

So, when they all dismounted from their horses one fine June morning at a little cabin hotel high up on the shoulder of Longs Peak, Mrs. Jefferson, Uncle Tom, and the children started afoot for Chasm Lake, while Uncle Billy and Aunt Jane joined an adventurous climbing party for the summit.

|

|

The precipitous face of Longs Peak from a rock shoulder 13,000 feet in altitude Photograph by Wiswall Brothers |

They found Chasm Lake quite as wild and romantic as Iceberg Lake, but this time, instead of looking down from the top, they looked nearly straight up half a mile from the water's edge to the towering summit of Longs Peak. It was just as notable an experience, though perhaps not so startling.

"You don't feel so shivery," Margaret put it.

"In this vast well formed by Longs Peak on the west, Mount Lady Washington on the north, and Mount Meeker on the south," said Uncle Tom, "originated the mighty glacier that hollowed out that immense glacier-bed to the east of us and piled up the Mills Moraine. This is one of the finest cirques that I have seen anywhere."

And indeed the spectacle was one of extreme grandeur. The enormous granite mass of Longs Peak, rising perpendicularly above them four times the height of the Washington Monument, looked from this point of view dark and forbidding. Its summit was lost in light, fleecy clouds. The Jeffersons had seen this mountain from the valley under many varying conditions, sometimes glistening white, sometimes so delicately blue that it seemed to merge into the sky itself, sometimes gloomy with storm-clouds, sometimes, at sunset, a rich glowing orange-red. But this was another and almost a terrifying aspect.

As they watched, the clouds thickened rapidly and dropped down into the great gulf almost to the spot where they stood. Scattering flakes of snow fell around them. Margaret shivered as they turned away, and Mrs. Jefferson looked anxious.

"I hope Billy and Jane will not meet a snow-storm on the summit," she said.

"Very likely they will have a little snow up there," said Uncle Tom. "They tell me that when it rains in the valley, it often is snowing on the summit. Clouds catch and hold the peak several times every day, and often it is snowing a little up there while down in the valley we have brilliant sunshine. But they have a good guide with them; and they tell me there have been no bad accidents."

"So they told me," said Mrs. Jefferson; but she looked worried until, an hour later, while descending the mountain, their horses brought them out again into almost a cloudless day.

The sun had long disappeared behind the higher mountains when the summit party returned to the hotel. Mrs. Jefferson gave a great sigh of relief when she saw six or seven horses approaching from far down the road. Until then she had not realized how much she had worried.

Aunt Jane cantered ahead of the party and soon was kissing the children rapturously.

"Oh how wonderful!" she exclaimed. "It was the greatest experience of my whole life. The climbing was harder work than I ever imagined, and it frightened one a little sometimes to climb around those steep places near the summit. But it was inexpressibly grand. And the view! Oh, that view! But wasn't it mean of Billy to leave us and come down first? What was the matter? Was the altitude too much for him?"

"Billy! Isn't he with you? He—he—isn't here," faltered Mrs. Jefferson.

"Oh!" cried Aunt Jane. "He must be here! We saw him start back ahead of us, and we didn't catch up with him—we did not see him again. He—he must be here!"

Aunt Jane's face paled. She clasped her hands and ran back to the approaching guide. Mrs. Jefferson ran into the hotel to find Uncle Tom.

|

|

Hallett Peak in July. A typical Rocky Mountain Gorge Photograph by W. T. Parke |

It was true. Uncle Billy, after having successfully made the ascent with the rest, apparently started back ahead of the party. The day had been overcast. Snow was falling fast before they left. The guide saw his footprints for a few hundred yards, when they became confused with others. The guide shouted for him, and Aunt Jane expected every minute to overtake him, but she did not doubt that he had safely reached the hotel.

The guide was plainly disturbed, but others of experience pointed out that no person ever had been lost or injured during the ascent of Longs Peak. Nevertheless, the Jeffersons were greatly alarmed, and, when Uncle Billy did not return at eight o'clock the guide was engaged to return over the trail and search for him. Uncle Tom insisted on accompanying him.

There was little sleep that night for the grown-ups. Several volunteers walked a few miles up the trail with the guide and Uncle Tom. But it was morning before Uncle Tom returned, nearly exhausted. They had found no sign of Uncle Billy; the guide had gone on to the summit.

Uncle Tom was exhausted; he was obliged to go to bed and sleep an hour or two, but several experienced mountain-climbers with another guide started up the trail after breakfast. Aunt Jane insisted on accompanying them, but Mrs. Jefferson remained below with the children.

And so it happened that, about noon, Aunt Jane, riding just ahead of the guide, met Uncle Billy limping on foot down the trail. He had been on the summit all night. It was not he whom they had seen start down ahead of them, but a member of another party. He had been peering over the edge of Longs Peak precipice into Chasm Lake at the time the party left, and, when he tried to follow, he could not find the trail.

"I do not know why I became so confused," he said, "for I found the trail easily enough this morning. But yesterday I was looking for it on the wrong side. It was snowing so hard that your tracks were all covered up. Then it seemed to get dark very suddenly. Then, while I was wandering around in the snow, chilled and stiff, night seemed to shut down all at once. So I gave it up and looked for a sheltered place among the rocks and crept in there.

"Do you remember, Jane, how you shared your lunch with me? Well, fortunately, I had my own still in my pocket, and, when I had eaten that, I felt very sleepy. The cold was dreadful, but I felt warmer after a lot of snow drifted over me. I held my hat over my face, and I must have gone to sleep right away. I think I was a little dazed.

"Anyway, when I woke up and began to struggle with the snow that lay on top of me, it was early morning. I climbed out. I think my ears are frozen, and I know one foot is, for I can hardly walk. I was awfully cold. But the minute I looked around, I recognized that big rock we saw as we came up. The night wind had blown away some of the new snow, and there was the trail.

"I don't know how I ever got down through the Trough. I had to feel my way. For a long distance, over the slanting places, I went on my hands and knees and brushed the new snow away. I felt for the trail with my hands. When I saw the Keyhole, I knew I was saved, but I was almost gone then. That is what gave me heart. Otherwise, I think I should have perished right there."

The guide helped Uncle Billy on his own horse and the party descended to the hotel, where, you may be sure, he received a very warm welcome. Uncle Billy was disabled for several days, and weeks passed before he lost a slight limp.

When, a few days later, the Jeffersons left the Rocky Mountain National Park for the Mesa Verde, Longs Peak glowed in the soft morning sunshine. Its bald slopes were a soft, delicate blue; and its summit, tipped with silver, shone in a warm red light. It was a most innocent-looking mountain.

|

|

A large beaver family has lived here for many generations Photograph by S. N. Leek |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

yard2/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 30-Oct-2009