|

Nez Perce National Historical Park |

|

Big Hole National Battlefield |

|

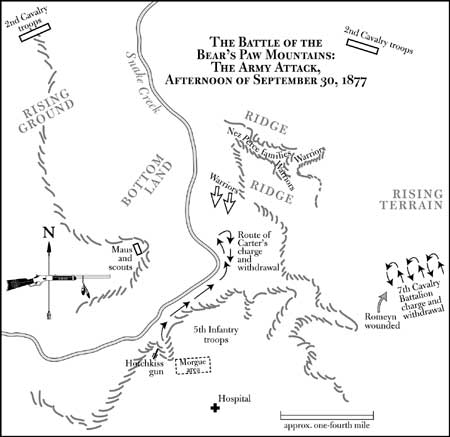

Chapter 12:Bear's Paw: Attack and Defense (continued) After the main part of the herd had been captured, Lieutenant Jerome brought his Company H up on the left bank of the creek opposite the village at the time the Fifth Infantrymen were firing into the Nez Perces' positions to relieve the Seventh Cavalry troopers pinned down east of the camp. Jerome's men opened a fusillade for several minutes that kept the warriors occupied and further helped Hale's soldiers. [53] (It may have been at this time that Jerome heard a voice call out from the Nez Perces' position: "Who, in the name of God are you? We don't want to fight." [54]) The action appears to have been preparatory for a general assault ordered by Miles on the Nez Perces' positions in the ravines adjacent east of their camp. There, in deep recesses, both natural and created by digging, the families kept out of sight, the warriors posted in neighboring coulees delivering enough firepower to keep the troops from advancing closer. By early afternoon, the warriors still trained a rigorous discharge against the disparate parts of the command that covered them on the east, south, and west. By then, too, some of Tyler's Second Cavalry soldiers held the hills below the north end of the camp on either side of Snake Creek. Miles now decided that a general assault on the tribesmen from the east and southwest would dislodge them and force their destruction or capitulation. "The only thing to do," wrote Lieutenant Woodruff, adjutant of the Fifth Infantry battalion, "was to make a clean sweep by charging along the whole line and drive them from the ravines and their village out into the open plains." [55]

Shortly after 3:00 p.m., orders to attack went out to the soldiers of the Fifth and Seventh battalions. Lieutenant Romeyn, in command of his own Company G and of the Seventh Cavalry battalion pulled back on the ridge beyond the ravine to the right of the Fifth Infantry, readied his men for action. [56] As he rose to his feet to signal the infantry to start with a wave of his hat, bullets from the Nez Perce positions several hundred yards away struck him, one passing through a lung. The lieutenant walked about seventy-five yards toward the rear and collapsed.

Romeyn's command, which had advanced with a cheer, quickly withdrew to its former position, several of the men also hit by the warriors' fire. [58] Consequently, only a unit composed of Companies I (fifteen men) and F (ten men), Fifth Infantry, besides "two or three odd men," [59] under Lieutenant Mason Carter, moved ahead at the appointed moment. They started forward through the ravine on the left of the Fifth's blufftop position while covering marksmen stationed there opened fire. Across Snake Creek, Lieutenant Maus and the Cheyenne and Lakota scouts, probably stationed on the point of land lately occupied by Jerome, likewise raked with gunfire the ravines inhabited by the families. [60] Woodruff, who accompanied the assault group, said that "we yelled and cheered and went over the steep bluffs, across a deep ravine, and right into the village." [61] There in the camp (which was at Joseph's sector) the approach abruptly stopped. Warriors ensconced in pits and gullies in the rising ground on the right front sent forth volleys that halted the troops and forced them back to the deep gully in their rear. Eight men were wounded (two of whom died) in the attack and withdrawal. The charge had failed, maintained Woodruff, "for the lack of support on the right and left." [62] Carter's men remained refuged in the ravine above the village for several hours, randomly shooting at the warriors when opportunity demanded. Woodruff, meanwhile, made his way back across the ground bordering the creek to report to Captain Snyder and Miles and to give instructions to Maus. Then he returned to Carter with orders to initiate a withdrawal from the position, and at sundown the troops started back, keeping from exposing themselves "by crawling on our hands and knees along a little ravine for about 20 yards." [63] Miles later appraised Carter's attempt:

At 5:30 p.m., Miles prepared a message notifying Howard, Sturgis, and Captain Brotherton of his situation:

Confronted with an exceedingly high percentage of loss in his assaults on the Nez Perce village, Miles determined that further such strikes would be equally unsuccessful. The fact that he had captured the people's livestock, thereby preventing their escape, decided him to prosecute them by laying siege to their position—in effect, to surround their lines with soldiers and strategically placed artillery and to pound and starve them into submission. Furthermore, Sitting Bull remained on his mind. Thus, as he wrote: "I determined to maintain the position secured, prevent the escape of the Indians, and make preparation to meet the re-enforcements from the north that the Nez Perces evidently expected." [66] By midafternoon of the thirtieth, Miles's force already held the high ground commanding the village and the primary Nez Perce refuge in the large slough running east from the northernmost camp, that of Toohoolhoolzote. It was into this broad coulee, covered by abruptly rising slopes on either side, that the women, children, and elderly had fled when the shooting erupted. Most of the warriors took advantage of the natural features of the ground in guarding this location from approach by the soldiers, and as the hours passed into the late afternoon, the people used whatever utensils were available (including some trowel bayonets taken from Gibbon's soldiers at the Big Hole) to begin to excavate more permanent entrenchments in the coulee floor. This work continued through the night, as the Nez Perces, desperate to protect themselves from the gunfire, worked to connect their shelter pits with each other—some via underground tunnels—and with the labyrinth of ravines and washes that emptied into the main draw. The loamy nature of the soil permitted the creation of cavities deep enough to accommodate whole families and their requisite supplies, moved in from the village. The defenders further secured their works by piling saddles and other items on the edges and covering these with earth removed from the interiors of the pits. "We digged the trenches with camas hooks and butcher knives," said one woman. "With pans we threw out the dirt. We could not do much cooking. Dried meat and some other grub would be handed around." [67] At least forty-one of these shelter pits were excavated or enlarged during the night of September 30-October 1. At the same time, to further protect the people, Nee-Me-Poo warriors prepared at least fifteen rifle pits ("in the most approved manner") along the inside slope of the ridges forming the sides of the ravine. "The next morning we had dirt and rocks piled up around pits, with holes to shoot through," remembered Yellow Bull. These entrenchments not only served to further protect the people sheltered in the pits below, but furnished additional and commanding points from which to return the fire of the soldiers. Yellow Wolf claimed that, should these points be overrun by the troops, the shelter pits were to provide the last line of defense for the people. [68]

While the Nez Perces began work to fortify their position, the army worked to consolidate theirs. The Fifth Infantry still occupied the bluff south of the village, while the Second Cavalry companies maintained positions on the plateau west and northwest of the village, and on the rising ground east of Snake Creek and northeast of the camp. The severely decimated units of the Seventh Cavalry battalion held the ascending terrain east and southeast of the camp. It was from the positions held by the Fifth and Seventh battalions that the last charge on the village had begun. Late in the day, and particularly with the approach of darkness when the gunfire lessened, these positions were further advanced and secured with the establishment of rifle pits along the crests of the ridges east and southeast of the village. [69] Perhaps because of the surer accuracy promised by infantry riflemen, if not because of the exhausted condition of the cavalry, the troops of those two units switched places after nightfall, with detachments of the Seventh occupying the bluff south of the camp, as well as a ridge west of Snake Creek, and the infantrymen taking station on the high ground on the east. [70] Lieutenant Woodruff reported that the infantrymen "encamped on the ridge where we had established the Hospital, keeping strong pickets out to watch the Indians and prevent them from escaping the village." [71] And regarding Company G of the Second Cavalry, Lieutenant McClernand remembered that,

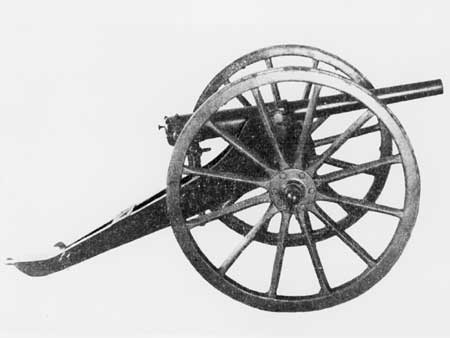

As the investment of the Nez Perces proceeded on the evening of September 30, the soldiers also improved the position of the Hotchkiss gun. Poised on the ridge west of the south bluff [73] and closely trained on the ravines harboring the people, the piece was readied to open fire at first light. The gun was a prototype, the first of its kind in the United States, and at Bear's Paw it saw its inaugural use in the combat with the Nez Perces. The steel breech-loading weapon weighed but 116 pounds, had a caliber of 1.65 inches, and employed a charge of six ounces of black powder to propel a two-pound explosive percussion shell a distance of as much as fifteen hundred yards. It was mounted on a light pressed-steel carriage that weighed 220 pounds. [74] East of the Hotchkiss, and behind the line on the bluff top, the dead who had been retrieved were laid out in a row and covered with blankets. [75] One thousand yards west of the gun and the camp of its supporting detachment, and beyond the camp of the Seventh Cavalry, Miles placed his headquarters in a protective bend on the right side of the creek bottom. [76] Farther west lay the infantry camp—the place where the foot soldiers congregated, slept, and ate when not on the line. Somewhere in the vicinity, probably adjoining the infantry camp, the pack mules were corralled. And one thousand yards away, across Snake Creek along a tributary to the northwest, the Second Cavalry battalion established its camp. For the moment, Dr. Tilton's hospital—evidently one tent—remained on the south bluff, in the depression behind the infantry line. [77] Late in the day, the shooting abated, the men on the line, including the Cheyenne and Lakota scouts, seemingly intent on picking off particular Nez Perce marksmen posted in ravines and rifle pits who kept up a harassing intermittent fire. "Yellowstone" Kelly and his scouts, who reached the command during the afternoon, took part in this action, and it was during the long-range dueling that Kelly's companion, Corporal John Haddo, took a bullet in the heart and died. Kelly also reported how one of the Indian scouts, Hump, "a bold and picturesque fellow," engaged a Nez Perce sharpshooter hidden in a rifle pit during an encounter that left the Nez Perce dead and the Lakota wounded. [78] Scout Louis Shambo remembered that "those Indians were the best shots I ever saw. I would put a small stone on top of my rock and they would get it every time. They were hitting the rock behind where I was lying which made me duck so hard that it made my nose bleed." [79] Sometime late in the afternoon one of Miles's packers who could speak the Nez Perce language hailed the Indians; one of them replied in English: "Come and take our hair[!]" [80] Many soldiers wounded in the day's fighting lay stranded between the lines and could not immediately be rescued. "[These] were left lying, except those that were able to crawl in our lines & that was few," stated one man. [81] Those who were able sought treatment at the hospital where Surgeons Tilton and Gardner labored to contend with the large number of casualties. In reference to the Nez Perces, Tilton wrote, "their marksmanship was excellent, and from the very opening of the fight, [we doctors] . . . had our hands full." One who received medical treatment was Private Allen, whose arm had been shattered during the initial fighting with Captain Hale's company. He described the scene:

Like Allen, Captain Godfrey sought attention for his injury received in the opening action. He related that he found Dr. Gardner, who examined the wound:

And Dr. Tilton recounted an incident involving Private Jean B. Gallenne, Company M, Seventh Cavalry, Hospital Steward Second Class, who was assisting the surgeons on the battlefield:

The soldiers wounded close to the Nez Perce positions who could not crawl to safety were of particular concern to the command. As the day turned to night and the firing subsided on both sides, plummeting temperatures and a wind-driven snow added greatly to their discomfort as they lay among comrades who had been killed. One man reportedly cried out to his comrades back on the line: "If some of you fellows don't take the blankets off them dead horses, I'll be damned if I won't freeze to death." [85] Some died; those who did not feared that the warriors would come and finish them off and perhaps mutilate them. Such fears proved unwarranted, for though some Nez Perce men came among them during the night, they came to take their weapons and ammunition. In one instance, a disabled sergeant readied his revolver as a warrior approached him in the darkness. The warrior spoke to him in English, telling him he would not harm him, then took the pistol and the man's cartridge belt, besides his watch and whatever money he had in his pockets. [86] Similarly, in another encounter an injured soldier begging for water lost only his ammunition belt, and the warrior left him a can filled with water. [87] The wounded in the hospital also passed a cold and dreary night. With neither wood nor troops to be spared to find some, there were few fires, only those made with buffalo chips for heating coffee. "Yellowstone" Kelly unrolled his blanket near the headquarters and noticed the soldiers sleeping nearby. Dr. Tilton distributed thirty blankets, and others were taken from the pack train, "but we felt the need of fire." Before dawn, Kelly was awakened and sent out to find the wagon train and guide it forward. [88] As Miles assessed the casualties for September 30, he found that his assault had been extremely costly. Of the three companies composing the Seventh Cavalry battalion, two officers and fourteen enlisted men had been killed, with two officers and twenty-nine men wounded (two died later); of the four companies of the battalion of the mounted Fifth Infantry, two enlisted men had been killed and four officers and twelve men wounded (three died later); and of the three companies of the Second Cavalry battalion one man was wounded. Total casualties thus numbered two officers and sixteen men killed, and four officers and forty-two men wounded. Two Indian scouts had also been wounded. [89] Scarcely one-half mile away across the battleground, as many as six hundred men, women, and children braced against the falling sleet and snow, many laboring through the night to improve their earthen pits and all awaiting to see what would happen next. Some buried relatives from among the twenty-two killed this day, but other bodies were too close to the soldiers' lines to be retrieved. "Children crying with cold," remembered Yellow Wolf. "No fire. There could be no light. Everywhere the crying, the death wail." [90] Among those who had fought hard that day and survived were Peopeo Tholekt, Two Moon, Shot in Head, Black Eagle, and Roaring Eagle. Among the dead were Chief Toohoolhoolzote, shot in a rifle pit on a ridge north of his camp; Ollokot, killed in the initial fighting; and three men killed accidentally by the Palouse leader Husis Kute—Koyehkown, Kowwaspo, and Peopeo Ipsewahk (Lone Bird)—while they were far in advance toward the soldier position southeast of the village and thought to be enemy scouts. Lone Bird had been one who complained of the slow pace of the assemblage as it passed through the Bitterroot Valley before the Big Hole battle. Ironically, Poker Joe (Lean Elk), in charge of moving the people in the wake of that encounter until they passed Cow Island, also lay among the dead—also the victim of mistaken identity. Not far from where Toohoolhoolzote's body lay, at a place later called "Death's Point of Rocks" about three hundred yards below the northernmost camp, five more Nez Perce men lay dead; two more had been wounded there. [91] The total number of Nez Perces wounded on the first day at Bear's Paw is not known. [92] |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Nez Perce, Summer 1877 ©2000, Montana Historical Society Press greene/chap12b.htm — 26-Mar-2002 | ||