|

SHENANDOAH National Park |

|

Biography of a Stream

Much of the rain and snow falling on the wrinkled back of Shenandoah National Park eventually nourishes its numerous streams. This water seeps out of the ground in springs where men have drunk for centuries. It drops over ledges in lovely waterfalls. It shelters a fisherman's prize, the brook trout. And it means life for a host of aquatic plants and animals. Though Shenandoah has no water bodies larger than mountain brooks, these give special beauty and a voice to the forest, and offer the naturalist a new realm to explore.

Thanks to outcroppings of resistant greenstone, many of the streams take vertical plunges in their upper or middle courses. Trails lead to the more spectacular falls as well as to many lesser ones. Whiteoak Canyon, with its six waterfalls and ancient hemlocks, is perhaps the most scenically rewarding of the stream valleys. Dark Hollow Falls, on Hogcamp Branch of the Rose River, besides being pretty has the virtue of being the closest—only 0.7 mile—from Skyline Drive. Overall Falls (near Matthews Arm campground), South River Falls, and several on Jones Falls Run and Doyle's River (south of Loft Mountain) also rank high in scenic quality. Many streams without notable waterfalls nevertheless make delightful hiking companions. Among the favorites in this category are Jeremys Run, Hughes River, North Fork of the Moorman River, and Big Run.

A number of the park's animals are found only in or near streams or boggy places. Turn over a submerged rock or stick and you are likely to find attached to it the cylindrical cases of caddisfly larvae. The larvae reach out from these little cases (made of sand or plant debris) to feed on material that washes by. Amazingly, each species can be identified by the type of case it builds. Nymphs of stoneflies and mayflies are common associates of caddisflies in the underwater world. Patrolling the surface of quiet pools, water striders feed on small insects that fall into the water. Aquatic bugs and beetles hunt between surface and stream bottom.

(Photo by Ross Chapple) |

Crayfish creep slowly along the bottom of park streams, or hide under rocks and debris. Feeding on organic material, these crustaceans are eaten by a variety of larger animals, including water snakes, barred owls, broad-winged hawks, raccoons, and mink.

With two feet in the water and two on land, as it were, most amphibians (frogs, toads, and salamanders) must have water for breeding and egg-laying, and some spend all their lives in or near water. The park's most common aquatic salamanders are the northern dusky, two-lined, and spring salamanders. Pickerel and green frogs can often be found at springs and along streams, especially in quiet pools, while toads may be encountered almost anywhere, though they go to water in the breeding season.

Salamanders are under cover and difficult to find during the day, but at night they are active and unafraid. For a different sort of nature experience, try finding them with a flashlight at night along streams, on wet rocks, and in springs. You should be able to watch them at close range as they go about their business.

Early each spring, an amphibian ritual takes place in a pool in the Big Meadows swamp. Soon after the ice melts, wood frogs and spotted and Jefferson salamanders migrate to this pool to mate and lay eggs. A knowledgeable amateur herpetologist, William Witt, who has watched this ritual for several springs, finds that the three species segregate themselves. The wood frogs lay their eggs in the southeast part of the pool, the spotted salamanders around the edges, and the Jefferson in the middle. After a short period of activity—with loud quacking of the wood frogs providing the music for the nuptial "dancing" of the spotted salamanders, followed by laying and fertilization of eggs—the three species disappear. The salamanders go underground for the rest of the year and the wood frogs disperse into wooded areas. For the people at Big Meadows, another spring has begun.

For the fisherman, of course, the park's most interesting aquatic animal is the brook trout. Some 46 of the park's streams support these fish, and for a few days after opening of the trout season their banks are well trodden. The most illustrious trout fisherman to visit the park was Herbert Hoover, who in the twenties built a retreat on the Rapidan River. Some of these rustic buildings are still maintained for visits by high government officials, and the trout in their lovely setting of boulder-washing cascades and sheltering hemlocks are still there. In most years, brook trout can be found in the higher waters, but soon after streams leave the park they become too warm to support these cool-water fish. If you approach a deep pool quietly, you may see trout hovering near the bottom against the current or lying nearly motionless under a log or rock waiting for prey. Their companions in the pool may be dace, darters, suckers and sculpins, all of which are common in the park. Some of the larger streams contain bass and sunfish in their lower park reaches.

A few birds and mammals are closely tied to water. The Louisiana water-thrush can be seen teetering on the streamside rocks or, more often, heard singing its musical accompaniment to the gurgling of the brook. Kingfishers work the lower reaches, where the fishing is best. Beavers, muskrats, and mink, all rare and local in the park, spend much of their lives in the water. Raccoons, common everywhere near streams, search there for crayfish and frogs.

Shenandoah's short, steep streams are highly vulnerable to the effects of drought and flood and thus provide an unstable environment. During very dry summers, most of them shrink to a series of disconnected pools. Fish trapped in these pools, enervated by a dwindling oxygen supply and rising temperatures, become easy prey. Robert Lennon, studying Shenandoah's trout, often observed water snakes preying on fish in isolated pools during the drought in the summer of 1954. Although other fish were more numerous, the snakes seemed to attack mostly brook trout, perhaps because these were the largest and were more debilitated by the high temperature. Floods, especially those during otherwise dry periods, can also wipe out many stream animals. Occasionally, hurricanes or other storms dump several inches of water on the Blue Ridge in a few hours and send rampaging torrents down the mountainsides, sweeping away anything in their paths, even large boulders. Recovery from the effects of drought and flood is usually rapid, however. Dr. Lennon found that within 2 years after the 1951-54 drought, brook trout and other fish had repopulated long stretches of streams. Fish food organisms, such as mayflies and stoneflies, no doubt recovered even faster.

One can see a good cross section of Shenandoah's terrestrial, as well as aquatic, life by following a stream from its headwaters high on the Blue Ridge to its exit from the park. Many streams offer this sort of biological spectrum. One of my favorites is the south section's Big Run; this stream seems to have more life in it than do most. Though it is pathless in its highest reaches, about 5 miles of Big Run is accompanied by a fire road.

Born in greenstone, maturing in quartzite, sandstone, and shale, and dying in Valley dolomite, Big Run changes character with each few hundred feet of drop. Like many streams, it has several beginnings. The highest source, at about 3,000 feet, is a spring beside a large boulder along the Drive near Loft Mountain Wayside. From here the water seeps and trickles down a slope covered with young red maples and yellow poplars interspersed with open, wet, fern-filled glades. As it gathers water in the upper end of Eppert Hollow, it gradually attains identity as a stream, with a consistent channel and a continuous voice. Here small stands of hemlock and yellow birch, mixed with oaks, sugar maples, and yellow-poplars, shade wet, mossy rocks. Juncos add to the northerly atmosphere. In the brook, crayfish and dusky salamanders hide under the stones.

About 1 mile below the Drive, the juvenile Big Run drops about 10 or 15 feet over a ledge of greenstone. The scene here is decidedly primeval. Great gray rocks guarded by giant hemlocks enclose the stream. Patriarchs of the past molder where they fell. The day Park Naturalist Frank Deckert and I visited this remote, shady glen, we found a weathered, rodent-chewed antler lying in the leaves. Who knows how many winters ago some old buck dropped it here? Now it seemed a perfect capstone to our experience of this wild place.

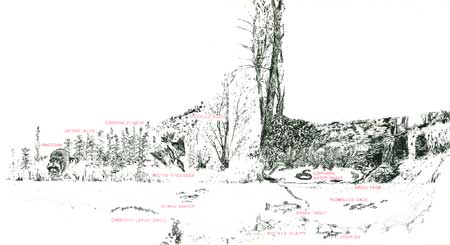

Big Run's quiet pools are good spots in which to look for wildlife. (Photo by Hugh Crandall) |

From this secluded stretch the stream hurries down to a tributary ravine which enters from the north. Here the pools contain brook trout during normally wet summers. The trees look smaller, perhaps indicating that cutting was more recent here than on the steeper slopes upstream. The first mosquito descended on us as we ate lunch. Herbert Hoover had specified that his fishing retreat must be above 2,000 feet to escape mosquitoes, and that limit must have been reliable. Our topo map placed us at 1900 feet. From here down to its junction with the other main fork of Big Run, the stream descends more gradually and takes on new characteristics. Oaks predominate in this forest, as they do in most of Shenandoah. The sprinkling of sugar maple we had found above now dwindled and virtually disappeared, and we noted only two yellow birches in a mile and a half. Instead of numerous hemlocks, we now found big white pines; and white-barked sycamores began to appear. Other small fish shared the stream with the brook trout, and occasionally frogs plopped into the pools. Near the mouth of Eppert Hollow, through which this major fork flows, we saw for the first time some alders along the banks. They signaled another change in the character of Big Run.

From this junction downstream, and back up the other major fork for about a half-mile, Big Run is a succession of long pools bordered by alders and willows and connected by short tumbles over sedimentary ledges. These pools generally harbor an interesting variety of aquatic life—trout, dace, darters, white and hog suckers, mottled sculpins, and, below the fire-road bridge, bass and bluegills. Aquatic insects include water striders, whirligig beetles, dragonflies, and the larvae of caddisflies, mayflies, and stone-flies. The spring salamander seems common; less so does the Blue Ridge red salamander, a subspecies of the northern red possibly introduced into Big Run by fishermen. Green frogs give their guitar-twang calls from some of the quiet, grassy shallows. Searching the pools for frogs and fish, water snakes weave sinuously across and under the surface. To sun, they climb into streamside bushes and debris, where they blend into mottled background. (These are not water moccasins; that poisonous species ranges no farther north than the very southeastern corner of Virginia.) And patrolling these fish-filled stretches of Big Run is an occasional kingfisher, which signals its presence with a loud, rattling call.

A Profile of a Mountains Stream in Shenandoah (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

From the mouth of Eppert Hollow on down, the forests flanking Big Run become increasingly dry. Rocky slopes rise steeply on both sides, and the afternoon sun can turn this basin into an oven. A heavy sprinkling of pines in the predominantly oak-hickory forest attests to the dryness. Pitch and Table Mountain pines are common in the upper parts of the basin, but in the lower reaches many Virginia pines also appear. Only along the stream does moisture-loving vegetation survive. Here tall white pines add their shade and stateliness, and twisting sycamores gleam white through the greenness. In late summer, scarlet cardinal flower and lavendar Joe-Pye-weed brighten the lower pools. Where there is water, heat encourages an abundance of life.

If it's a hot day, one is tempted to submerge himself in one of the smooth-rock bathtubs provided by Big Run. There are nice ones near the fire road bridge. If you plan to explore downstream from here, you might appreciate a dip, because the pathless trip can be hard work. In its last mile or two in the park, Big Run winds through a narrow cut in the mountains known as The Portal. This is a scenic, rough stretch—well shaded, rock-walled, with bass and sunfish now joining the fish population. Once through The Portal, however, Big Run seems to decide that life in the level lowlands is not worth it, and sinks abrubtly into its gravelly bed. Thus ends one of the park's most life-filled streams.

Though never heavily settled, the Big Run basin suffered repeated burning and much hunting and trapping in pre-park days. But now those wounds are healed. Except for rock slides and stream openings, the forest is unbroken. Deer, bear, and turkey have returned in abundance. From high vistas one looks down upon a wild, wide-yawning basin revealing no scars from man's disruptive presence. It is easy to understand why Shenandoah-lovers reserve a place in their hearts for Big Run.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |