|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

Wolves, Moose, And The Balance Of Nature

Through the cycle of the seasons, and face of the landscape; and populations of living things fluctuate, sometimes violently. Over centuries, slow climatic change brings new assortments of plants and animals. Yet the island remains a green place teeming with life, and the diversity of life on it perhaps continues to grow. How does all this individual change result in a collective stability, and can we find in this ecological drama some lessons for our own species?

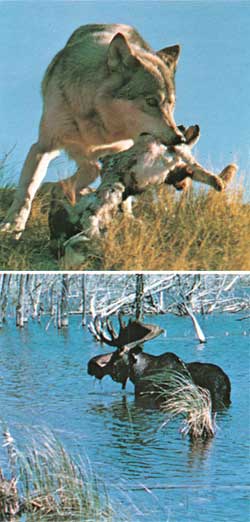

Depending mainly on moose, Isle Royale's wolves also prey upon the snowshoe hare. (Top photo by Greg Beaumont; bottom photo by Robt. G. Johnsson)) |

The now-famous story of the island's wolves and moose can begin to show us how the Isle Royale web of life hangs together. Sometime in the first decade of this century, it seems, moose became established (or re-established) on the island. This significant happening was probably related to a regional change in the vegetation. Between 1890 and 1910, logging and fires in the northern Great Lakes area destroyed much of the reindeer lichen, on which caribou heavily depend, and created open areas where tree seedlings and shrubs—food for deer and moose—could flourish. Consequently, caribou decreased and deer and moose increased. Isle Royale's moose immigrants, which probably swam singly or in small groups from the Canadian mainland, were perhaps pressured by a growing population to seek new feeding grounds. As sometimes happens when a new species reaches an island with suitable habitat, an irruption followed. By 1930, when Adolph Murie studied the situation, the moose population had reached an estimated 1,000 to 3,000 animals, and a large part of the woody vegetation within their reach was overbrowsed. Murie correctly predicted that starvation and disease would soon decimate the herd.

The first large die-off occurred in the winter of 1933. By 1936, when fire burned a quarter of the island and further reduced the browse supply, moose numbers had dropped to an estimated 400 to 500. From this low point, the herd increased again, aided by luxuriant resprouting on the burned area. By the later 1940's there were numerous signs that die-offs would again occur.

A wolf pack withdraws after an unsuccessful attack on a cow moose and a yearling. |

Boom-and-bust cycles might have continued had it not been for the arrival, in the late 1940's, of the timber wolf. Through the first half of the century its smaller cousin, the coyote, had been present; but coyotes do not prey upon moose. By 1957, somewhere between 15 and 25 wolves inhabited the island. Coyotes, probably killed off by the intolerant wolf, had disappeared. In 1960 David Mech, a Purdue graduate student studying wolves for a doctoral dissertation, determined after many hours of aerial observation that the wolves numbered 21 or possibly 22. This population was composed of a large pack of 15, which hunted mostly on the southwest two-thirds of the island, and small groups of two or three that hunted mostly on the northeast one-third and along the north shore.

From an aerial census made in March 1960, Mech estimated the moose herd at 600. Apparently the wolves were controlling the herd at a level below that at which the food supply would control it, for browse species were growing in areas where they had not been evident for decades. Furthermore, the calculated annual kill of adults by wolves was nearly equal to the calculated number of yearlings surviving to join the breeding population each spring. And apparently the herd was healthy: the proportion of cows bearing twins as opposed to a single calf was much higher than it had been in the 1930's—a sign of good nutrition.

Research in the late 1960's and early 1970's indicated that the moose herd may have increased. An aerial count in mid-winter, 1972, produced an estimate of about 900 animals. Counts of moose pellets by researchers from Purdue and Yale suggested that the population in the early 1970's was 1,000 to 1,500. Wolf numbers remained in the low 20's. Thus it appeared that a slow rise in the moose population was underway, though wolves had not decreased.

Although wolves certainly have a damping effect, the ultimate determinant of moose numbers is the island's food supply. That supply depends on the stage of forest succession and the extent of browsing by moose. The relationship between these two factors is delicate and complex. In many parts of the northern forest, succession proceeds to a stable state in which spruce and fir form a closed canopy. In the course of this succession, food for moose declines as trees grow above browsing height and some favored browse species are shaded out. On Isle Royale, where moose densities are among the highest known and where wind takes a large toll of trees, succession seldom proceeds to a pure spruce-fir stand. The toppling of trees creates openings in which shrubs and saplings spring up, producing much browse. Browsing is so heavy in many of these areas that the young trees cannot grow up. This maintains a good food supply for a long time but eventually can result in elimination of the browse species and replacement by grass and unpalatable shrubs or by spruce. If it continues, such heavy browsing will cause certain tree species to drop out of the forest: mountain-ash essentially everywhere, aspen and cherry almost everywhere, paper birch and fir in many areas, and yellow birch in some areas. Only fire or a major decline in moose numbers will break this trend: major fires create so much new growth that moose cannot suppress it all; and a population decline has a similar effect. Thus the moose population cannot be expected to stay indefinitely at its present high level without the advent of fire.

Just as available browse limits moose numbers, available moose would ultimately limit wolf numbers. But there is considerable evidence that social pressures may set an upper limit to wolf density, even when the food supply goes on increasing. Within each pack there is a "dominance order;" each animal knows its social standing with respect to all the others. Furthermore, there are separate dominance orders among males and females. Normally, the lead, or alpha, male mates with the alpha female. Matings between subordinate animals are often prevented by the lead pair. As a pack grows, sexual rivalries tend to become more and more complicated, and stress increases. Reproduction may also be inhibited by the dominance of large packs over smaller ones. If the territories of such packs are not well separated, the small pack probably has no chance of raising pups. Thus as wolf numbers grow in an area, increasing social controls apparently restrict reproduction.

Death of pups is another, perhaps greater, control on numbers. On Isle Royale, between 2 and 5 females are fertilized every year. This would produce a rapid population growth if it were not for the high mortality rate of pups. Many pups die during the denning period, for causes not yet well understood. Others succumb after leaving the den. If a pup survives its first 6 months, or until fall, its chances of living several more years are good.

Though wolves have the potential to reproduce rapidly, and sometimes do so after heavy reductions, in most wolf populations the proportion of pups is small. This is the case on Isle Royale, where the density of wolves, about 1 per 10 square miles, is one of the highest known. This is possible only because of a very high moose density of 40 to 50 per 10 square miles. At present, the wolves apparently are holding moose numbers steady or to a slow rise, and environmental and social factors are keeping wolf numbers stable.

Among Isle Royale's other animals, there are examples of both stable and unstable populations. The red squirrel population, though high, does not change greatly. As we have seen, this species has no really efficient predator, like the marten, on the island. Its numbers are regulated largely through reproductive control. Females bear only one litter, averaging three young, in a year, and many do not reproduce at all in poor cone years. Thus the birth rate is low, the survival rate is high, and the chatter of red squirrels remains perennially ubiquitous.

Deer mice, though without competition from other small mammals except red squirrels, remain rather thinly distributed over the island. In favorable habitat, there are only 1 or 2 per acre. This low density, which is comparable to that on the mainland, must represent the limit allowed by available food and shelter, and suggests that the island deer mice have not occupied the ecological niches of other small rodents found on the mainland but not on the island. Though deer mouse numbers in early spring may be only one-eighth of those in late August, numbers from one spring to another do not vary greatly.

The flicker and other woodpeckers help to keep insect populations within bounds. |

On the other hand, snowshoe hares are famous for their boom-and-bust population cycles. With peaks coming regularly at about 10-year intervals, these cycles exhibit extreme swings in the far north, less pronounced ones in the southern part of hare range (which includes Isle Royale). Like rabbits, hares have a high reproductive potential, and variations in the reproductive rate, influenced by availability of nutrients, seem the prime reason for fluctuations in the hare population. Diseases and predation are factors in the downward part of the cycle.

Predators that depend on hares are forced to take the same population roller-coaster ride. On Isle Royale, red fox numbers seem to peak about one year behind hare peaks, though careful estimates of the fox population have not been attempted. If the lynx, now rare or absent on the island, were more common, its population swings could be expected to parallel those of the hare.

Insect populations, also, sometimes explode and then fade. The larch sawfly boomed early in this century, killed many larches (tamaracks), and then dwindled. The spruce budworm multiplied fast in the 1930's, causing concern for the firs, a chief winter food of moose, then also overabundant. But since that time the insect has quietly retreated. The outbreak of the large aspen tortrix in the 1970's may give another example of the normally temporary nature of such explosions. As with other animals, insect outbreaks are eventually controlled by food supply, predators, disease, parasites, and weather, and by aspects of the species' life history.

What determines the relative stability on instability of populations? This is a complex question with no simple answer, but an important part of it lies in the diversity of species present. The more species present in an area, the more stable its populations are likely to be. This is so because fluctuations within individual species tend to cancel each other out, and because various species act as a check on on a food supply for others. If, for instance, Isle Royale had more species of small mammals, it probably could support more foxes, and more small mammals might reduce the swings in the fox population by providing more choice of food, and a more stable total supply, in the critical winter season. If, say, voles were on the island, their numbers might be high at a time when hares were scarce, thus allowing more foxes to survive the winter. The relative stability of wolf and moose numbers on the island, though the wolf is dependent on the moose and is its only predator, is an interesting exception to the principle.

As a rule, islands have fewer species of animals than do mainland areas of comparable size and habitats. This is true mainly because for many species islands are difficult to reach. And if an established species is somehow wiped out, it may be a long time before new colonists arrive to try again. On the mainland, migration from one area to another is much easier. A number of species of vertebrates, as we have seen, and perhaps hundreds of invertebrates that live on the north shore of Lake Superior are not found on Isle Royale. Perhaps if all these were present, animal numbers on the island would be somewhat more stable. Generally speaking, however, population fluctuations on Isle Royale do not seem appreciably greater than they are on the mainland.

However much or little they may fluctuate, the populations on Isle Royale are determined largely by the quantity and quality of vegetation. This is so because green plants, directly in the case of herbivores, and indirectly in the case of carnivores, supply virtually all the food for animals. Exactly which species and how many of each are present at any given time depend on the species available in the region, their particular food requirements, and a number of other factors, some which we have just considered.

Green plants, such as blueberry and bog rosemary, are the foundation of terrestrial food chains. (Photos by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Green plants, in turn, depend on water, carbon dioxide, and the energy of sunlight to produce the sugar from which the compounds necessary to sustain life are built. Plants also require other mineral nutrients from the environment for there own maintenance. So the potential amount of vegetation on Isle Royal is controlled by the amount of incoming energy from the sun, the amount of moisture, and the mineral nutrients in the soil and air. The nutrients further determine the quality of the vegetation as food for animals. In northern coniferous forests ??? the water percolating down through the soil carries much of the needed nutrient below the reach of plant roots, and the low rates of evaporation do not allow a counter-flow of minerals upward. This mineral deficiency together with the lower amount of sunlight, results in less production of plant ??? matter here than in the deciduous forests to the south, and considerably less than in tropical forests. The island's forests are, however, much more productive than arctic tundra, which suffers from greater deficiencies. And current research by a Yale University team suggests that Isle Royale supports more animal life than do many other parts of the northern forest at similar latitudes. They suspect that this can be attributed to the island's underpinning of basalt and sedimentary rocks, which contribute more of the essential minerals to the soil than does the granite that underlies large areas elsewhere.

The breeding habitats of great blue herons have been greatly diminished except in protected environments such as Isle Royale. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

The relationships between incoming energy, minerals, plants, and animals can be studied particularly well on islands because the water prevents much interchange with the surrounding region. On Isle Royale, for instance, the interdependencies of moose, wolf, and vegetation are much easier to study than they are in mainland areas because here the animals are virtually "penned in" by Lake Superior: their numbers are little affected by immigration and emigration. The added fact that nature is allowed to operate unhindered creates an outdoor ecological laboratory of exceptional value—one that has attracted scientists since the middle of the last century.

What does Isle Royale tell us about our own relationships with nature? One clear message is that we should encourage diversity. For instance, we create potentially very unstable situations by devoting large areas to one crop, which can be devastated by a single insect species or disease. Such monocultures limit the animal life that can act as checks on exploding pest populations. And we never know when some obscure plant or animal may be needed to provide something required for the welfare of man or his environment. But the fundamental message is that man, like other animals, is ultimately controlled by his environment. If we do not stabilize our numbers, we face the unpleasant alternative of starvation, disease, and warfare. And if we continue to poison our environment, it will eventually poison us.

For the earth, too, is an island—an island in the sea of space. All that we have is here, finite, wrapped within our round shore.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |