|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

Life Comes To The Island

At the time of Isle Royale's birth, many forms of life were pressing northward as the warming climate rapidly destroyed the ice and exposed the land. Which ones first crossed the water to those smooth gray rocks, pounded by frigid waves, and to those bare, sandy hills?

Then as now, the wind and water carried spores and fragments of algae and lichens, and some of these settled on the new surface. Algae gained a foothold in wet places, and lichens pioneered mostly on rock, wet or dry. The air, the lake waves, and perhaps also wandering birds carried seeds of higher plants from the forests and grasslands south of the ice border. Some of these seeds—those from plants best adapted to cold, sterile conditions—germinated and grew on thin glacial deposits or in cracks in the rock.

Spiders, by virtue of their abundance and variety, have important roles as predators in most terrestrial communities. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Quite likely, many of the early colonists were tundra plants, of species now found only in the Arctic or on high mountains. Gradually these grasses, sedges, dwarf birches and willows, and other low-growing plants wove a green carpet over the gray-brown hills, except in the many places where rock still resisted. Perhaps here and there, in sheltered spots, spruce trees grew.

Lichens, the first plants to become established in a new, rocky environment, help prepare the way for mosses, ferns, and eventually flowering plants such as blue bell or three-toothed saxifrage. (Top photo by Wm. Dunmire) |

Where there is plant food, animals can follow, and no doubt the vanguard was not long in coming. Airborne insects and microscopic animals drifting down upon the greening landscape now could survive. Birds could begin nesting here. A few caribou may have arrived across the lake's winter ice. Close on the heels of the plant eaters came animals that preyed upon them, including insects, spiders, hawks and owls. If there were caribou, wolves may well have braved the 15-mile ice crossing to hunt them.

On the Isle Royale of 10,500 years ago, we can imagine a scene much like that of the subarctic today. Mats of grasses and bright flowering little plants cover the ridge-tops; shrubby birches and willows fill the draws; and down in the wet valleys scattered spruces raise their dark spires. Small bands of caribou, pausing frequently to scan the landscape for wolves, move up the hillside, browsing shrubs and nipping ground plants. But this is a transitory scene in the story of Isle Royale; for the forest is coming.

As the ice retreated, the land, relieved of its great burden, slowly rose. The basin's waters, also lifted somewhat by the rising land beneath, flowed out through the lowest available outlet. Over the centuries, the trend was for land areas to rise higher above the water level, as downcutting and escape through successively lower outlets generally resulted in lowering the elevation of the water surface.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

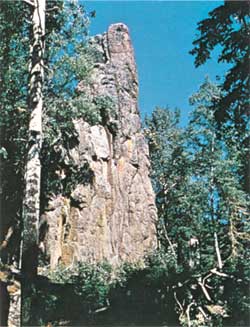

By about 10,500 B.P. (before present), the glacial ice had receded to the northern edge of the Superior Basin, which was then occupied by Lake Minong. This lake, which emptied by way of the Au Train-Whitefish strait (Munising, Michigan, area) and St. Marys Strait (Sault Ste. Marie area), remained stable for many years, thus building well-defined shorelines which are easily traced today. On Isle Royale, Lake Minong shore features are found at elevations of about 680 to 765 feet. (Subsequent uneven uplift accounts for the variation.) They include beach ridges (just west of Siskiwit Bay one is followed by the Feldtmann Ridge Trail), sea cliffs, and sea stacks. Of the latter, Monument Rock, on the Lookout Louise Trail, is the most spectacular.

As North American climates continued to warm and the continental ice sheets melted further, vegetation changed accordingly. On Isle Royale, spruce gradually took over, first forming scattered open groves and later, dense forests. Following soon came smaller amounts of pine, fir, aspen, and paper birch. With the establishment of these species, the forest must have looked much like the dominant forest on Isle Royale today.

And what of its animals? Many of these, too, were species present now. In the Great Lakes forests 9,000 years ago roamed marten, fisher, wolverine, lynx, snowshoe hare, beaver, muskrat, porcupine, wolf, woodland caribou, and moose, to name some of the larger ones. But which of these swam, rafted, or crossed the ice to Isle Royale we have no fossil record to tell us. It is tempting to imagine mastodons here, but these great beasts apparently preferred open rather than closed forests, and by 9,000 B.P. they were nearing extinction. The island's complement of insects and birds probably included many of today's. In the shore waters swam trout, herring, and whitefish, cold-water species that had been able to survive near the glacial front.

The spring peeper, which may have reached the island on driftwood, breeds in water but lives as an adult in shrubby vegetation. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

The warming trend that forced the retreat and eventual disappearance of the continental ice sheets reached a climax some 6,000 years ago. The climate then was warmer and drier than now, and prairie grasslands displaced forests as far east as Ohio, Indiana, and southern Michigan. On Isle Royale this climatic change resulted in the decline of spruce and an increase of pine, oak, maple, and yellow birch. The pollen record in bogs suggests that toward the end of this warm period hemlock, basswood, elm, walnut, and hickory also may have grown on the island, though none of these is present today. Spruce-fir forests probably survived only in cool, wet areas near the shores, in swamps, and on some north-facing slopes, while the deciduous hardwoods covered most of the uplands.

Animal life probably changed in a similar way, with increase of the more southerly species and decrease of northerly ones. Reptiles and amphibians, being cold-blooded and therefore requiring fairly warm climates, quite possibly survived on the island for the first time. Some aquatic species, such as newts and painted turtles, may have been able to swim through the temperate water. Other turtles, frogs, snakes, and salamanders, as well as their eggs, may have been carried on or in driftwood to these shores. Most probably they came from the Ontario shore to the north and east, since the prevailing currents come from that direction.

Warmer water during this period no doubt also aided fish in crossing the big lake and becoming established in Isle Royale waters. Some larger species may have found a new home throughout the lake, while some smaller ones accompanied "rafts" of flotsam to sheltered water around the island, and then traveled upstream to interior lakes. At the same time, the cold-water fishes such as whitefish and trout, which probably had become established in Isle Royale lakes during colder times, now could not tolerate the warmer inland waters and died off in all but the deepest lakes. Lake trout, for instance, now live only in Siskiwit Lake, while whitefish survive only in Desor and Siskiwit.

Monument Rock, a sea stack at an elevation of about 700 feet above sea level, is a remnant of the shoreline of ancient Lake Minong. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

About 5,000 B.P., near the end of the warm "pine period," the level of the three upper Great Lakes, now all at the same elevation, stabilized long enough to form another prominent shoreline. This gigantic body of water, known as Lake Nipissing, formed beach ridges, sea arches, and other features on Isle Royale at elevations now from 640 to 660 feet above sea level. (Lake Superior is about 600 feet above sea level.) During this stage a bar forming across a cove mouth created Lake Halloran, a sea arch was cut on Amygdaloid Island, and Suzy's Cave, facing Rock Harbor, was carved out by the waves. By this time, with lake levels only 40 to 60 feet higher than now, Isle Royale had nearly reached its present configuration. Siskiwit Lake had been cut off from the big lake by a low ridge, and most of the other inland lakes had also been formed. (In another 3,000 years or so, the present Great Lakes would be formed and Isle Royale would have emerged to its present extent.)

Isle Royale's biologic story since that time has been shaped by increasing coolness. Spruce-fir forests have spread to all but the highest, driest areas, tightening a noose of competition around the remaining stands of sugar maple, yellow birch, and pine. Some "southerly" animals probably have been eliminated. Whether this trend will continue into another ice age or will shift toward greater warmth, we can only guess.

Gravel beaches have formed at some indentations in the rocky shoreline. (Photo by R. Janke) |

What life inhabits the island at this particular point in its long-short history? Many species for which the climate is suitable either could not make the trip across or, once arrived, could not become established. Most of the plants and birds of the nearby Canadian mainland have succeeded on the island, but many other forms of life have not. Among the missing vertebrates are black bear, white-tailed deer, raccoon, striped skunk, porcupine, eastern cottontail, and a number of small rodents, as well as snapping turtle, spotted and red backed salamanders, and leopard frog. The island's wildlife drama today has only a few principal mammal actors: wolf, moose, beaver, snowshoe hare, red squirrel and deer mouse; the few other mammals are uncommon, rare, or ecologically unimportant. Perhaps the small size of the mammal cast heightens our interest in it; certainly it focuses the action of the play.

Many processes of creation and destruction continue today as they have since rotten ice first melted off this piece of land. Ever so slowly, rock weathers and helps to form soil. Still responding to the removal of its tremendous burden of ice, the northern part of the Superior Basin rises a foot or more per century. Waves carve into the rock shores, make beaches, and build bars underwater across coves. Lichens and the plants that follow create forest on rock. Creeping mats of vegetation form "cataracts" over the eyes of lakes and eventually fill them. We witness on youthful Isle Royale the earth's primordial work.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |