|

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS National Monument |

|

Desert Vegetation, The Principal Attraction (continued)

Succulents

On the upper bajadas and along the foothill slopes of the Ajos, the Growlers, the Puerto Blancos, and among the ridges of the Sonoyta Hills, succulent plants grow in greatest density. As you leave the open valley floor and begin to ascend a bajada toward the base of the mountains, you will observe a gradual change in the ground cover. Vegetation becomes tangled, plants are larger and thriftier, the number of trees and large cactuses increases, and new species appear. Shreve wrote that "the distance from the base of the mountain at which these changes begin and the extent of the change are dependent on the rainfall and the character of the detrital material. . . . In general the amount of change is directly proportional to the size of the mountain from which the bajada descends."

The large number and variety of succulent plants (those which have developed special water-storing tissues) have given to the extensive landscape covered with this type of vegetation the name "Arizona succulent desert." Storing water for frugal use during long periods of drought is one of the methods that plants have evolved for maintaining life under rigorous desert conditions. Some plants, such as the yuccas and agaves, have developed water-storage tissues in their leaves, and they are known as leaf-succulents. Many other plants, called stem succulents, store water in their stems. Still others produce greatly enlarged roots which serve as underground reservoirs effectively protected from the drying effects of wind and sun.

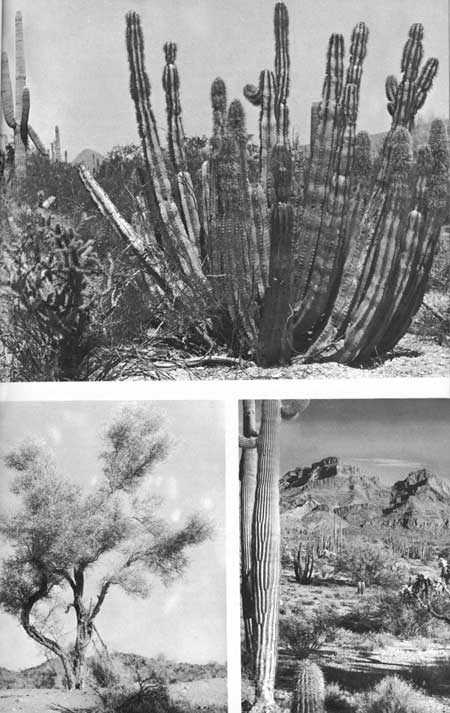

Common in northern Mexico, the senita cactus (above) reaches its northern limit along the southern edge of the monument. Smokethorn (lower left), found sparingly in the southwest corner of the monument, is more plentiful farther west. Succulents grow most luxuriantly on sloping bajadas and foothills, such as those of the Ajo Mountains (lower right). |

One of the latter group, found sparingly in the monument, is the deerhorncactus, locally called "nightblooming-cereus." The turnip-shaped root of this species ordinarily weighs from 5 to 15 pounds, but specimens weighing up to 80 pounds have been found. The slender-stemmed plants are quite inconspicuous except in late June or early July, when they produce, during the night, large white flowers, exquisite and fragrant, that are locally known as reina-de-la-noche (queen-of-the-night). A closely related species, with huge clusters of dahlia-like roots, also occurs in the monument.

Succulents that have developed water-storage tissues in their stems are the most abundant. They are represented by the many and varied leafless cactuses. Some cactuses have jointed stems, others are blocky and barrel shaped, while still others have long, cylindrical stems without joints.

In this last group is the famous organpipe cactus, which finds an ideal habitat on the sloping bajadas. These curious plants dominate the landscape on the lower slopes of the mountains and along the rocky ridges that interrupt the outwash plains.

Some of the huge plants grow as tight clumps, with many green stems that range from 5 to 20 feet in height. These generally unbranched stems usually spring from a common root system at ground level. Other individuals are languidly sprawling, with fewer, less upright arms. Stems have from 12 to 19 ribs, each producing a surface ridge with a long row of star-shaped clusters of stout spines. Blossoms, which are brownish green to pinkish lavender and are about 1-1/2 inches in diameter, usually open during May nights, on or near the tips of the branches. In midsummer, spherical fruits mature. Their reddish pulp is juicy, sweet, and nutritious, and it is harvested by birds and small mammals.

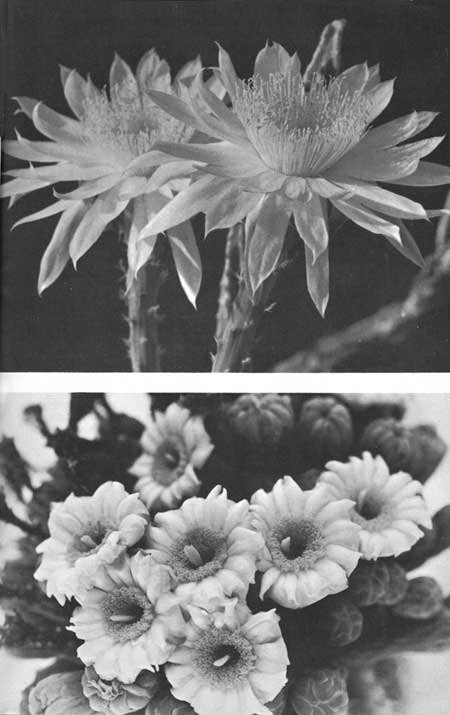

Opening at night, blossoms of the deerhorncactus (above) and saguaro cactus (below) lend their brief beauty to the desert scene. |

These fruits are also eaten by the Papago Indians, who call them "pitahaya dulce." Some of the fruits are eaten fresh and others are cooked, the pulp and seeds being separated from the juice for storage. The juice is boiled down to form a thick syrup; the pulp is dried and later used in jam; and the seeds are ground to form a mealy paste. Members of the present generation of Papago Indians on the reservation east of the Ajo Mountains have fitted themselves more and more into the modern pattern of life, depending less, as time passes, on native food sources. But caves with smoke-blackened walls and other indications of former Indian camps give evidence that the region along the southwestern base of the Ajos was at one time the scene of colorful Papago pitahaya harvest activities.

Organpipe cactus plants are sensitive to frost. Although a light freeze does not kill the plant, damage is done to the growing stem tips which stops further elongation. Frosted stems sometimes branch below the damaged tip, and the plant sends up new shoots from ground level. Susceptibility to frost injury apparently is an important factor in limiting the range of the species to a climatic zone which is relatively frost free. This may explain the scarcity of organpipes much beyond the head of the Sonoyta Valley. The abundance of this spectacular species, together with the wealth of other Sonoran Desert plants and animals, was one of the reasons this biologically rich area was selected for preservation as a National Monument.

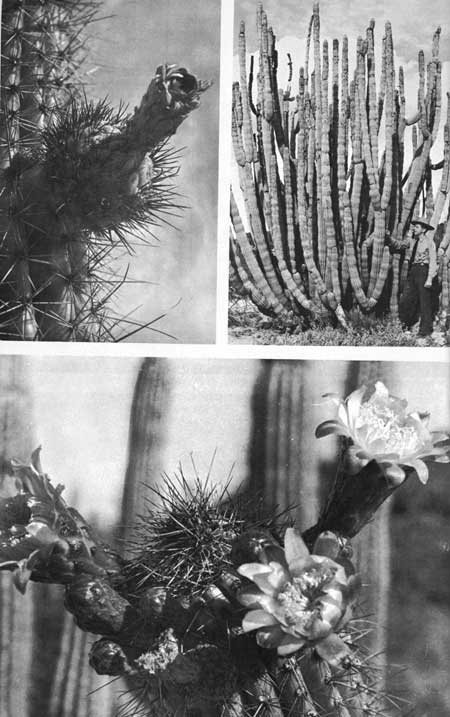

Organpipe cactus is a striking sight on the monument's foothill slopes and sometimes grows to great size (upper right). In May it produces small blossoms (below). The sweet, juicy fruits (upper left) are eaten by Papago Indians, who call them pitahaya dulce. |

Although near the western limit of its range, the giant saguaro cactus is abundant on the bajadas, where rocky, well-drained soil provides suitable conditions for the development of several especially dense stands, or "forests." Largest of the succulents in the United States, the saguaro occasionally reaches a height in excess of 50 feet and a weight estimated to be as much as 10 tons. These plants have a distinct trunk, with from as few as 1 to as many as 50 branches, usually upright. Some plants may attain an age of 200 years.

The large, white-petaled flowers of the saguaros open at night, usually in May, among dense clusters of buds on and near the ends of the branches. Blossoms usually close before mid-afternoon of the following day. The egg-shaped fruits mature in late June and early July, splitting open when ripe to reveal a scarlet interior containing a mass of juicy pulp filled with a myriad of black seeds. The enormous seed crop stands in sharp contrast to the very small number of young plants that survive in even the most favorable years. Growth of seedlings is extremely slow, so that a 10-year-old plant may be little more than 1 inch high. Later growth is variable, and a 3-foot plant may be from 20 to 50 years old.

The saguaro occupies an important niche in the desert life community, for it furnishes food and shelter for many creatures. Bats are important pollinizers. Insects, seeking nectar from the flowers, attract numbers of flycatchers. The ripening fruits are eagerly consumed by birds, including white-winged doves, which also obtain nectar from the blossoms. Fruits that fall to the ground are eaten by rodents, coyotes, and other earthbound animals. A heavy toll of the seed crop is taken by ants. Nest pockets are drilled in the spongy stem tissues by Gila woodpeckers, and hawks and owls build their bulky nests in the forks of the branches. An insect-carried bacterium produces a necrotic disease that has killed many saguaros in overage stands.

Until recent years, saguaro fruits formed an important item in the diet of desert Indians and are still harvested in some areas. The Papagos considered them so important in their economy that they established the harvest season as the beginning of their new year. Skeletal poles, or ribs, of dead saguaros were used by early settlers in building shelters and fences. The saguaro blossom has been adopted as the State flower of Arizona, and the plant's unique silhouette is considered a trademark of the Southwest.

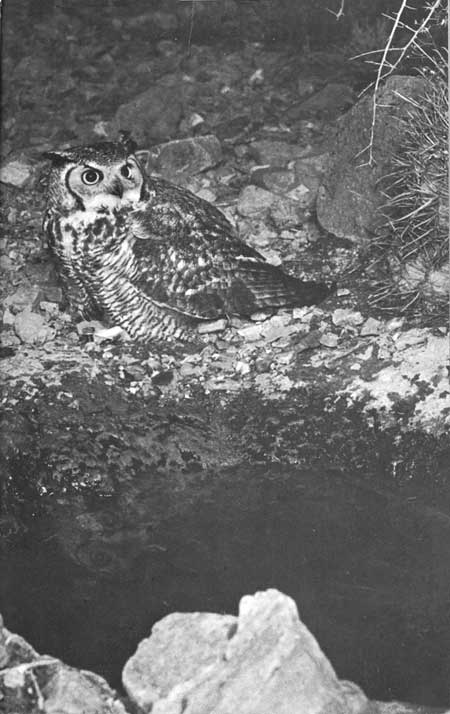

Great horned owl, shown here by a pool at night, often builds its nest in the forks of a saguaro. |

A large group of joint-stemmed cactuses, which grow in the form of large shrubs or small trees, are called chollas. Similar in general appearance, they still present striking differences that interest both the veteran cactophile and the desert neophyte. Largest of these cactuses is the Sonora jumping cholla, also called tree cholla, which sometimes attains a height of 12 feet. The sturdy trunk and thick candelabra-like branches form an irregular open crown of densely spined joints.

Joint connections are so brittle that a person or animal brushing even lightly against the spine tips carries away a piece of the stem. So light a touch is required that some persons have declared that the joint actually leaped off the plant to imbed its spines in their clothing; hence the name "jumping cholla." Another name, chain-fruit cholla, refers to the chainlike hanging clusters of previous years' fruits. Flowers, which are small and pink, form on the pendant fruit clusters.

Much smaller than the Sonora jumping cholla but even more conspicuous because of its compact growth and extremely dense armor of straw-colored spines is the Arizona jumping cholla, also called silver cholla and Teddybear cholla. This usually grows in miniature forests on south- or west-facing slopes. The easily overlooked flowers, which are yellowish green, open from March to May. The short joints fall around the base of the plants, where they take root in sandy soil. Those that roll downhill or are carried some distance from the plant by water, wind, or animals may become established and help to extend the area covered by the pygmy cholla forest.

Several small species of cactus, called pencil chollas, are found mingling with the tangle of growth along margins of washes. Most noticeable among these is the tesajo, or Christmas cholla, whose bright-red fruits persist throughout the winter.

Sometimes expanding into large and conspicuous clumps, the cactuses with broad, flat, leafless joints, or pads, are called pricklypears. Prickles are of two types: long stiff spines, and clusters of small, usually brownish, hairlike barbs.

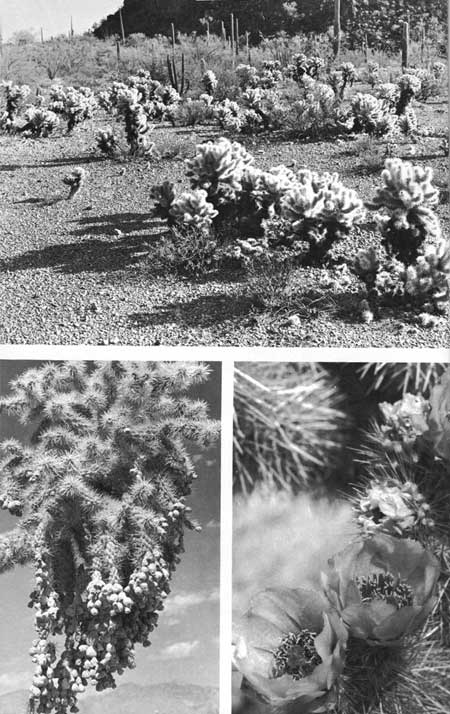

Dense stands of Arizona jumping cholla (above) form miniature cactus forests. The plant's yellow-green blossoms (lower right) are protected by a thicket of silvery spines. A close relative, the Sonora jumping cholla (lower left), has persistent fruits that have given it the local name of "chain-fruit cholla." |

Largest and most spectacular of the many flat-jointed cactuses is the Engelmann pricklypear. It has jointed stems that may reach 5 feet in height, and it grows in clumps which may become 10 to 15 feet in diameter. Blossoming in April-May, the flowers are large and numerous and have bright-yellow petals. They mature in autumn as reddish-purple fruits, called tunas, which are eaten by skunks, coyotes, birds, and other animals. The fruits, enjoyed raw by the Indians, make delicious jelly.

Sometimes mistaken for a young saguaro, the California barrelcactus, or "bisnaga," may be identified by the stout reddish central spine in each cluster which curves at the tip, resembling a thick-shanked fishhook. The blossoms, which are yellow or orange, develop in an open-centered cluster on the crown of the plant from April to June. The pale-yellow fruits, about the size and shape of a small hen's egg, ripen in early winter and are eaten by deer, rodents, and birds.

Among the small ground-hugging cactuses there are several groups, some of their representatives so tiny as to be overlooked except when in blossom. These are known as the fishhook, pincushion, and hedgehog cactuses. Largest are the hedgehogs, among which the Engelmann echinocereus is widespread and has several variants. Fruits of some species are about the size of strawberries and are juicy and edible. The plants bloom during March and April, their large flowers making bright spots amid the low-growing desert vegetation. Petals vary in color from lavender to deep-purple and magenta. The plants consist of small, open clumps of cucumber-shaped stems, 6 to 12 inches tall, with long, strong spines.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |