|

SAGUARO National Park |

|

the rhythms of nature

Natural landscapes may appear unchanging, but this is illusion. Within the apparent constancy, daily and seasonal cycles, fluctuations in numbers, and long-term change are the rule.

Daily cycles are obvious to those who are about at the edges of the day. Take 24 summer hours in the cactus forest of Saguaro National Monument. When the first light comes over the mountains, curve-billed thrashers and cactus wrens sing noisily among the chollas. Other birds soon join in. The early morning walker is likely to hear peccaries grunting in the mesquites along a wash, or see mule deer staring at him, frozen like statues before sudden flight to a sheltering thicket.

At midday, the scene is quiet. Nothing stirs under the baking sun except perhaps a vulture, soaring on the hot air currents. The desert creatures have not gone—they are in the shade of bushes or underground. Even some of the plants are "taking a siesta," having folded their leaves or closed their leaf pores.

Soon after sundown the desert comes to life again. The birds give a subdued version of their morning's vocal performance. Tarantulas begin their slow, stately walk over the ground searching for prey or mates. Coyotes stretch and howl—a prelude to the evening's hunt. As night falls, rattlesnakes emerge from their cool retreats to search out kangaroo rats, which in great numbers are scrutinizing the sand for seeds. And through the night, creatures of many other kinds hunt food to last them through another broiling day.

The rhythmic patterns of the daily cycle are paralleled on a larger scale through the year—seasons of activity follow seasons of quiet. In the desert, rain or lack of rain marks the changes, though gradually rising or falling temperature adds its impact.

The gentle rains of winter prepare the way for the year's greatest burst of activity. By March, spring flowers are blooming and birds are starting to nest. Snakes begin to come out of hibernation. April and May see the apex of spring activity, as insects swarm around the flowering plants, and birds take advantage of this proliferation of food to raise their young. The desert now is yellow with the blossoms of paloverde, mesquite, acacia, and brittlebush.

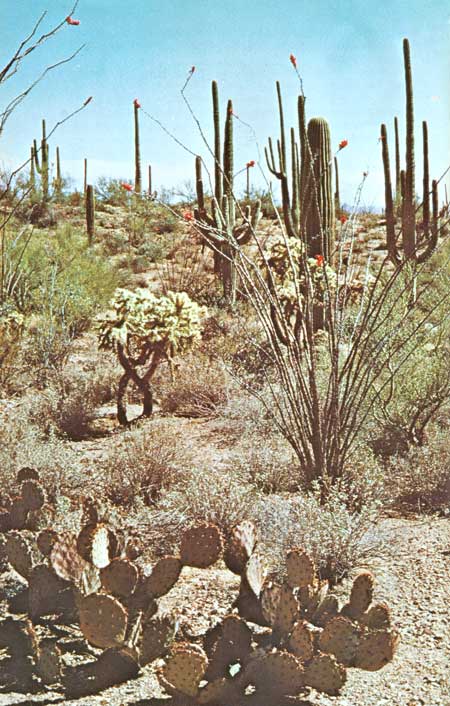

Desert vegetation near Red Hill, Tucson Mountain Section. (Photo by Harold T. Coss, Jr.) |

But April also marks the beginning of a drought that intensifies through May and June, making these last 2 months the year's parching crucible in which reproductive ability is tested. If winter rains have been meager, the heat and drought of May and June can kill all the young of many birds. Some birds, such as Gambel's quail, may not even attempt to nest in a dry year. Conditions may be so harsh at this season that some mammals, such as the pocket mouse, close up shop completely, sleeping the days away underground.

Relief comes with the rains of July and August. Now the summer annuals spring magically from the ground, perennials put forth new leaves, and saguaros do all their growing for the year. This summer burst of plant growth is accompanied by a new hatching of insects, which allows a few more birds to nest, and along with the new vegetation supports a larger pyramid of animal life generally. Among the new animals that reappear are toads, which now emerge from their long sleep in the soil to mate and lay eggs in the pools formed by summer rains.

When the last torrential rain of August or September falls, a new dip in the yearly cycle of activity begins. This one is not so deep, not so trying, as the drought of early summer, but it too is a time of relative quiet. Roundtail squirrels go underground to sleep until cooler weather comes. Now the migrating birds slip through, hardly noticed among the mesquites and paloverdes. Butterflies lay their eggs, in preparation for a new generation beyond the winter. Signaling the last phase in the yearly cycle, wet canyons turn yellow and brown as cottonwoods, willows, and sycamores present a pale version of the spectacular foliage displays seen in the East.

While these daily and seasonal cycles are following their well-known courses, each species of plant and animal is undergoing its own fluctuations, in a constant struggle that generally goes unnoticed. For the balance of nature is not a static one, but more like the rocking of a seesaw on its fulcrum. The population of a species goes up one year, down another—depending on the weather, the food supply, predators, competitors, and a thousand interactions that reverberate through the community in which it lives. The numbers of some species, like the Gambel's quail, fluctuate wildly from year to year, while those of others, such as the harvester ant, remain quite stable. But the oscillations of the seesaw, big and little, average out from year to year so that the species maintains itself in the community. The other members are going through the same thing, in a system of checks and balances that over the short run keeps the whole community nearly constant.

But over decades, centuries, or longer, the fulcrum of the seesaw moves: the larger environment changes, and the community and its constituent plants and animals must change with it or perish. Such changes may be climatic, as we saw with the formation of the Southwestern deserts; or it may be geologic, as with the rising and partial disintegration of the Rincon Mountains. The efforts of plant and animal species to meet such changes constitute in large part the story of evolution, for new environments spawn newly evolved forms of life. Evidence of such evolution we have seen in the plants of the Sonoran Desert, notably the giant saguaro cactus, whose prickly ancestor lived in the West Indies only 20,000 years ago.

Thus nature is ever-changing; and the inexorable rule for all living things is, "adapt or perish." Before technological man enters the scene, the slow evolutionary process can keep pace with the changing environments, though here and there a species is dropped by the wayside. Generally, communities of living things reach new equilibria without serious disruption.

But what happens when man, with his machines and his passion for progress, institutes changes of a speed and kind and on a scale drastically different from those brought about by earthquakes, storms, shifting climates, and other natural phenomena? What happens to the living things that have adapted to the harsh desert environment when that environment is drastically altered?

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |