|

SAGUARO National Park |

|

Numerous and Varied Animals

Many species of reptiles, birds, and mammals as well as of plants have become adapted to the soils and the climatic limitations of the Tanque Verde and Rincon Mountains, and of the surrounding deserts. These creatures have found the food and shelter essential to life in the plant communities and habitats within the monument. Animals are influenced by elevational differences to a lesser degree than plants but are somewhat restricted to the life zones of their habitat. However, because of their great mobility, many birds and some of the larger mammals spend the winter in the desert, moving upward in the summer to the cooler life zones of the highlands, practicing a sort of "vertical migration."

When many people use the word "animals" they are thinking only of mammals; and they are likely to be surprised at the statement that animals are numerous in the desert. If you travel by automobile, the desert may appear devoid of animal life, especially in summer. You may see only an occasional rabbit carcass on the road, or a raven or vulture circling overhead. Nearly all desert animals have learned that survival means conservation of moisture. Therefore, during the heat and low humidity of midday, loss of moisture may be greatly reduced by remaining quiet in the shade of a creosotebush or mesquite tree, or resting underground in a burrow. Reptiles are unable to endure extended exposure to excessive heat or direct sunlight because they have no internal control over body temperature. In the spring and autumn, however when the sunshine is not so intensely hot, desert reptiles are often seen abroad at midday. In cool weather they need the sun's heat to raise their body temperature to the level of comfort and effective activity.

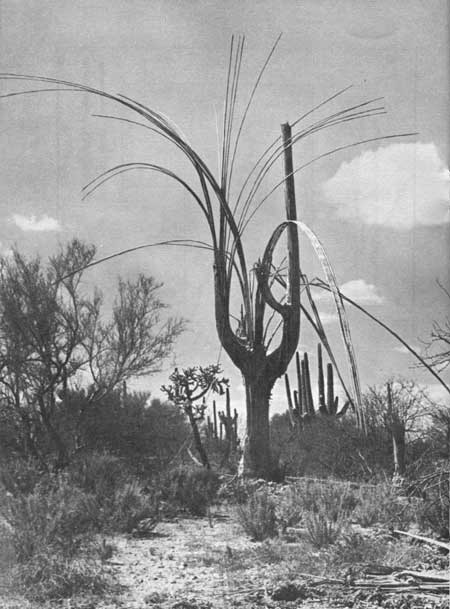

Even in death the Saguaro is spectacular. After the succulent tissue dries and falls away, the many-ribbed skeleton bleaches under the desert sun. |

INSECTS OF THE DESERT

Insects are generally not bothered by excessive heat, many species carrying on their activity during the hottest hours. This is especially true when the plant blossoming season is at its height. Flowers of the mesquite, palo verde, catclaw, saguaro, and other desert plants are "alive" all through the day with many species of winged creatures seeking nectar and pollen, or preying on other insects attracted to the blossoms. The insects, in turn, provide food for various species of birds, the flycatchers flocking to parts of the desert where nectar-yielding flowers are numerous. By their abundance and because of the absence of extreme cold, the desert climate enables insects to be active throughout much of the year and support a considerable bird population.

Insects play a far more important part in the plant and animal life of the desert than is usually realized. Many desert flowers must be insect pollenized to produce viable seeds. Birds of the flycatcher groups depend upon insects for food; and even the seed-eating birds, during the nesting season, rely upon insects to provide the enormous quantities of food and moisture required by their fast-growing nestlings. Many other desert creatures, including certain snakes and lizards and some spiders, depend upon insects for food. The body juices of the insects provide the all-important moisture which these creatures can get from no other source. Bats, too, are insect eaters, spending the hours of darkness in seemingly aimless and erratic flight while foraging for moths and other night-flying insects which visit the usually white or light-colored blossoms of night-blooming plants.

Some species of insects may become so numerous that they threaten to wipe out the plants on which they live. In a national monument this would endanger scenic values. Insects may also spread plant diseases. A serious necrosis disease which has reduced stands of mature saguaros has been traced to bacteria spread by larvae of a desert moth. Bark beetles annually damage or kill numbers of pinyons and ponderosa pines in the Rincon Mountains, but have been kept sufficiently under control by their natural enemies so that their ravages have never reached epidemic proportions in the monument.

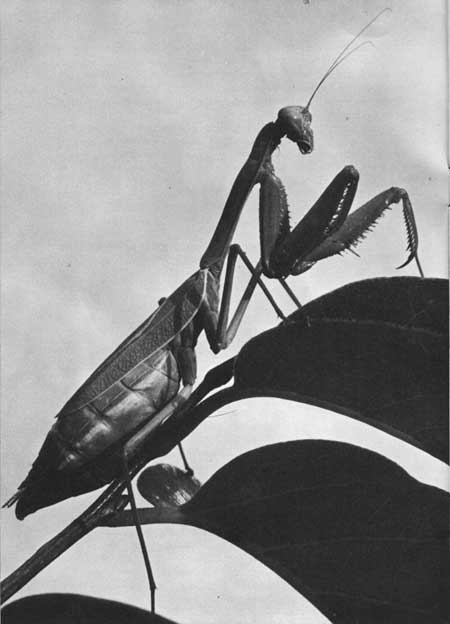

The fierce appearing praying mantid is harmless to humans. |

Among the common spectacular insects is the TARANTULA HAWK (Pepsis formosa), a large blue-black, red-winged wasp that preys on large spiders. Paralyzing the spider with its sting, the wasp lays a single egg on its victim thereby assuring an abundance of living food for its young. The PRAYING MANTID (Stagmomantis californica) is another large insect, usually green in color making it inconspicuous among the foliage of desert plants which it frequents in search of small insects. Ants of many species are active almost everywhere in the desert harvesting seeds of various plants. Some species construct mazes of underground nest tunnels depositing the excavated materials on the surface, forming conical, sometimes craterlike, anthills.

There are a number of other jointed-leg creatures, including the spiders, which are somewhat similar to insects. Among these, the North American TARANTULAS (Aphonopelma sp. and Dugesiella sp.) are famous for their large size and formidable appearance. This has given them the wholly undeserved reputation of being dangerous to humans. The really dangerous creatures are the SCORPIONS of which several species are found in the monument. Only the small straw-colored scorpion has venom known to have been fatal to humans in some cases. The other scorpions found in the area are capable of inflicting painful stings which have only localized and rarely serious effects.

The brown or black tarantula spiders are timid and retiring. Their poison is less potent than that of a honey bee. |

REPTILES—AN INTERESTING PART OF THE WILDLIFE

DRAMA

Except for small lizards, reptiles are not much in evidence in the monument. Nevertheless they are present and are important in the various plant-animal communities in which they are active. Almost all of the lizards are insect eaters, cooperating with birds in keeping the countless numbers of these crawling and flying creatures within bounds. A notable exception is the GILA MONSTER (Heloderma suspectum) largest of the lizards found in the United States. It is also the only poisonous species of lizard in this country. The Gila Monster is especially fond of bird eggs, and also eats nestlings and small rodents, obtaining necessary moisture from their body juices. These food habits are quite similar to those of the several species of snakes found in the monument, the majority of which are perfectly harmless to humans.

The Gila monster. |

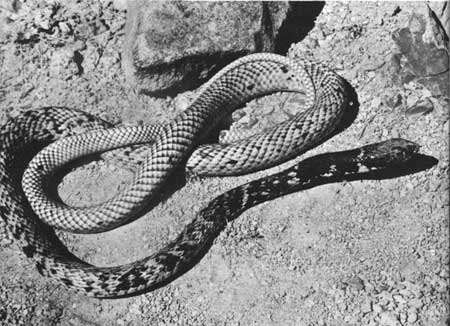

As the lizards help to hold down the insect population, so the snakes are important in preventing the buildup of large numbers of rodents which might result in widespread damage to vegetation. Visitors to the monument rarely have opportunity to observe snakes since they are in hibernation during the winter and remain in the shade or in underground burrows during the hot part of each day during summer. Perhaps those most frequently seen are the GOPHER SNAKE (Pituophis sayi affinis) and the RED RACER (Masticophis flagellum frenatus). Many desert snakes hunt only at night, while others that are normally active during days of moderate temperature, become night hunters during hot weather. Although not abundant, there are several kinds of rattlesnakes in the monument, the commonest species in the desert being the WESTERN DIAMOND RATTLESNAKE (Crotalus atrox). Except for the small and very rare SONORA CORAL SNAKE (Micruroides euryxanthus), rattlesnakes are the only poisonous snakes in the monument.

Slender and light-bodied, the western red racer or whipsnake climbs into bushes and low trees in search of bird eggs. |

Western diamond rattlesnake. |

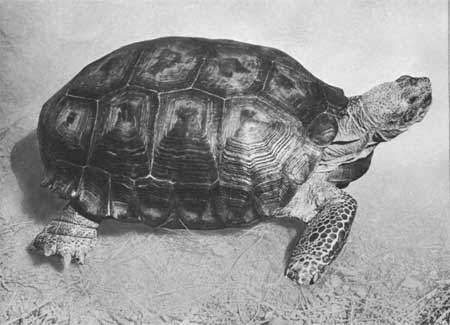

Don't be surprised if, while following a desert footpath you come upon a plodding tortoise. This is a bona fide desert dweller, the DESERT TORTOISE (Gopherus gassizi), which is a vegetarian.

The desert tortoise. |

As might be expected, amphibians are scarce in the monument because of lack of permanent water. However, the few springs and seeps furnish excellent places for several species of amphibians to breed. Best known among these are the DESERT TOAD (Bufo punctatus) and the CANYON TREE TOAD (Hyla arenicolor). Most spectacular of the desert amphibians and largest toad in the United States is the huge COLORADO RIVER TOAD (Bufo alverius) sometimes found around residences in the evening when outdoor lights attract swarms of insects upon which these big amphibians feed.

Colorado river toad. |

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |