|

ROCKY MOUNTAIN National Park |

|

Plant Communities (continued)

THE MIDDLE BELT

Above an altitude of approximately 9,000 feet, the forests show a different aspect. This is another zone, called the Subalpine by some botanists and Canadian by others. It is characterized by forests of stately ENGELMANN SPRUCE (Picea engelmanni) and ALPINE FIR (Abies lasiocarpa). You can tell one from the other by touching the needles. The spruce needles are 4-sided, rigid to the touch, and sharp-pointed; the fir needles are flattened and softer to the touch. From your car, you can spot the firs by their erect, dark-colored cones, mostly high in the tree. This type of forest is the climax developed in this climatic belt which receives twice as much snow and rain as the zone below. This relatively abundant moisture (much less, however, than in most of the eastern States with their broadleaf forests) supports a luxuriant conifer cover. Wildflower gardens of rare beauty and startling luxuriance are found in natural openings within the forest. The distinctive blue COLORADO COLUMBINE (Aquilegia coerulea), which ranges from the lowest elevations up to 13,000 feet, seems to reach its best development here.

THE BLUE COLUMBINE—COLORADO'S STATE FLOWER. |

Other plants of the open forests in this zone include the WHITE GLOBEFLOWER (Trollius albiflorus), with its cream-colored, cup-shaped flower; the MONKSHOOD (Aconitum columbianum), with its helmeted blue or white flowers; the ELKSLIP MARSH-MARIGOLD (Caltha leptosepala), with numerous oval white sepals which are often mistaken for petals; and the strikingly beautiful PARRY PRIMROSE (Primula parryi), with clusters of brilliant purple flowers often growing along the edge of a stream. Common shrubs include the MOUNTAIN-ASH (Sorbus scopulina), whose large clusters of white flowers are replaced by bright red berries in autumn; the BEARBERRY HONEYSUCKLE (Lonicera involucrata), better known in the Rockies as twinberry, a honeysuckle with large ovate leaves 3 to 5 inches long and pairs of yellow flowers; and the WILD RED RASPBERRY (Rubus idaeus), with prickly stems, 5-petalled white flowers, and delicious red fruit which is relished by birds and hikers alike.

In the cool, shadowed depths of the forest where light is dim, another community of plants is found, including the CALYPSO, or FAIRY-SLIPPER (Calypso bulbosa), a dainty orchid with rose-colored blossoms formed in a curious slipperlike shape; the PYROLAS (Pyrola spp.), a group of low, hardy perennial herbs with white or pink flowers having 5 thick petals and 10 stamens; the CORALROOT (Corallorhiza multiflora), a plant which, getting its nourishment from decaying vegetation, has no green leaves, but bears purple-spotted flowers on its brown stem; and the TWINFLOWER (Linnaea americana), a trailing plant of the Honeysuckle Family, often forming dense mats with upright, forked flower stems bearing a pair of pink, bell-shaped flowers.

After fire or other catastrophe wipes out the spruce-fir forests, a cycle of natural revegetation must take place before the climax forest again becomes established. The first step in this recovery process is the appearance of fireweed and many annual herbs, among which shrubs such as JAMESIA, or WAXFLOWER, become established, and aspens begin to appear as succession plant types. They are replaced eventually by longer-lived lodgepole pines, also sunloving and tolerant of burned or denuded sites. The trees increase the wetness of the forest floor, provide the shady sites necessary for seeds to grow in, and shelter the young spruce and firs as they slowly increase and approach maturity. Eventually, the spruce and fir trees crowd out the pioneers which have helped them get established. This dense spruce-fir forest seems to resist competition of other species and will maintain itself indefinitely by gradual replenishment of its own kind, unless again it is fire-swept or there is a change of climate. The spruce-fir forests of the park seem to be as nearly fixed and static as forests can be, or, in the scientists' words, they are the climax forest for the sites they occupy.

LODGEPOLE PINE FORESTS ALONG TRAIL RIDGE ROAD. —A. R. Leding photo. |

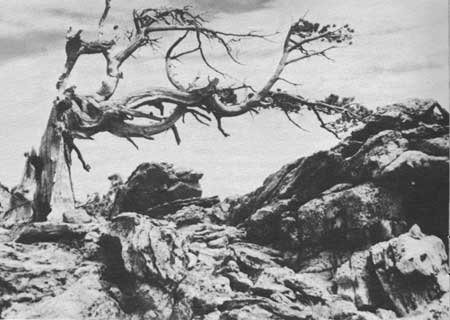

The higher part of the Subalpine Zone (10,500 to 11,500 feet) is often called Hudsonian for its biological similarity to the region around Hudson Bay. It is a sort of frontier zone where the climate is more severe. Not only is it colder, but it is much windier, and loss of water by evaporation is much greater than it is a thousand feet lower in altitude. Although spruce and fir remain the dominant species, they are usually shorter and less symmetrical in appearance. Near the upper limits of this zone the trees are twisted and grotesque, often flat and ground-hugging, sprawled behind boulders or fingering into the dwarf willow clumps so characteristic of the alpine mountaintops. Here also, the only 5-needle pine in the park, LIMBER PINE (Pinus flexilis), a rocky soil tree of the Subalpine Zone, assumes its most picturesque aspect. Limber pine at timberline is readily identified by its grotesque, twisted, ragged appearance. Several splendid specimens can be seen beside the Trail Ridge Road about a half mile above Rainbow Curve. The name, limber pine, comes from the ease with which the branches can be bent without breaking. The cones are often 6 inches long, the largest of any conifer in Colorado.

LIMBER PINE AT TIMBERLINE. |

The limber pine stands in the shadow of threatened extermination by a tree disease—blister rust. This is a fungus disease which attacks, girdles, and destroys all species of 5-needled pines. It has already wrought havoc in many parts of the country. Like so many of our virulent forest diseases, it was introduced from abroad. Since no known natural checks on it exist in this country, it is almost impossible to eradicate. Fortunately, it spreads to pines only from its alternate hosts, the WAX CURRANT, and other species of Ribes, and, if they are eradicated from the vicinity, the pines can be preserved. The work of eradication is costly, but without it the limber pine might be lost forever from the park. The Federal Government is doing such work in selected forests on the northeast slope of Longs Peak and near Estes Cone where many splendid specimens of this tree occur.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |