|

BADLANDS National Park |

|

Animals (continued)

MAMMALS

Early explorers and settlers tell of bison and pronghorn in great numbers ranging the grasslands above and below the great wall of the badlands. Audubon bighorn, whitetail and mule deer, and occasional bands of American elk and pronghorn fed on the grass-covered tablelands and along the stream courses. Early Indians used this area as a hunting ground.

Bison once roamed the grassland in vast numbers |

Westward settlement sounded the death knell for many of the wild animals of the plains. With the coming of the hide hunters in the late 1800's, bison almost disappeared from the scene. Pronghorns were reduced to only a few scattered bands. Bighorn, which were found in the early days on Sheep Mountain, have disappeared—eliminated by the hunter's rifle. Of the larger mammals, only a few deer and pronghorns remain. Conforming to the objectives of the National Park Service, all animals that now live within the monument's boundaries are protected. American elk, bison, and a few bighorn may still be seen in Wind Cave National Park and Custer State Park, in the nearby Black Hills.

Deer are commonly found in the Black Hills and are occasionally seen in some parts of the badlands. Both the WESTERN WHITETAIL DEER, a relative of the common deer of the East, and the MULE, or BLACKTAIL, DEER live in this section of the State. The former is found here in restricted numbers. Its large, white tail, waved like a warning "flag" when the animal is alarmed, is the famous trademark.

The mule deer is widely distributed throughout the West, and in the Black Hills region is more common than the whitetail deer. The large mulelike ears and the black-tipped tail are distinguishing characteristics.

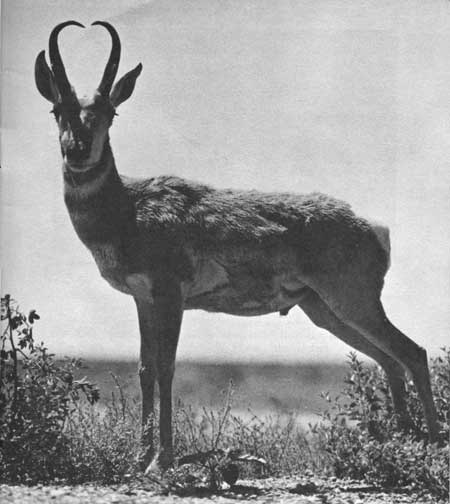

The pronghorn E. P. HADOON PHOTOGRAPH |

A few small bands of PRONGHORN still live near the badlands, but they are seldom seen. In some open prairie sections of the West, the pronghorn remains one of the important game animals. The name comes from the conspicuous fork, or prong, on each horn. Although it is often called "antelope," the pronghorn is a member of a different family. True antelopes never shed their horns; the pronghorn sheds its horns annually, the new horns forming on the permanent bony cores.

The pronghorn is an animal of the open prairie; its keen eye sight and fleetness of foot help it to detect its natural enemies and make good its escape. The large white rump patch serves much the same purpose as the waving white flag of the whitetail deer for when alarmed the pronghorn flashes its warning signal to others of the band.

A coyote FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE PHOTOGRAPH |

The COYOTE is one animal of the great plains that has persisted and continues to live and raise its young in spite of modern civilization. Whereas its larger cousin, the gray wolf, has been almost completely wiped out in most sections of the West, the coyote has successfully adapted itself to the changing environment created by man. In spite of organized attempts to exterminate it, the coyote has held on, and has even extended its range in some areas.

Small mammals, such as rabbits, ground squirrels, mice, and chipmunks, and all forms of carrion form a substantial part of the coyote's diet. It is a common dweller of the badlands and often may be heard at night singing its weird lament.

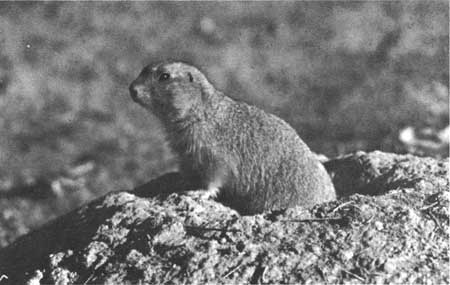

A young prairie dog at his den entrance CARL P. KOFORD PHOTOGRAPH |

The BLACKTAIL PRAIRIE DOG is not a dog, but a fat, colony-dwelling ground squirrel about the size of a full-grown cottontail. Because of its characteristic sharp bark, it has acquired the name "dog." During the early history of this country, "dog towns" were widely scattered over the western plains. Gradually, the prairie dogs were destroyed, until today they are seldom found in their old range. In areas administered by the National Park Service they are protected with other native wild animals.

During the summer, the prairie dog feeds on the green vegetation surrounding its home. During its semihibernation in winter, when snow covers the ground, it lives on its accumulated fat, emerging from its den only on the warmest days to lie in the sun.

The burrow extends downward as much as 10 to 15 feet at approximate right angles to the surface, with several short branches radiating from it. The entrance is protected from flooding by a mound of earth that is kept in constant repair by the occupants. This dike also serves as an observation post for the sentries that are constantly on guard throughout the town. When danger approaches, those nearest set up a chatter that in turn is picked up by the neighbors. Thus the warning echoes across the colony. As the danger nears, they disappear down their holes with a flip of their stubby tails and a parting yip of alarm

The PORCUPINE, one of this country's largest rodents, is a common resident of the pine forest; it is also found in the more wooded parts of the prairie country, including the badlands.

During summer, it prefers the tender shoots of small shrubs and green herbs, and in winter it lives on the underbark of trees. It is an expert climber. Normally, "Porky's" quills lie flat and are well hidden by the long yellowish-white guard hairs that cover the head and back. The hollow, white, black-tipped quills are 1 to 2-1/2 inches long. Contrary to the mythical story, the porcupine does not throw its quills. Peace-loving by nature, it goes its solitary way; but when danger threatens, it is immediately on guard. It is unfortunate for the animal that comes too near, for with a slap of the broad tail, the quills, which are minutely barbed on the ends, become deeply imbedded in the flesh of the victim. They are very painful and extremely difficult to remove.

The RACCOON, common throughout much of the United States, is found occasionally in the forested fringes of dry creekbeds and in wooded pockets of the great north wall. Its diet is varied; it relishes fish and small mollusks and feeds on small rodents, insects, fruits, and nuts. It does most of its hunting at night, preferring to roll up and sleep in its nest during the day. In the coldest part of the winter it remains in the den, appearing when warmer weather comes in early spring.

The WHITETAILED JACKRABBIT is one of the largest of several species of jackrabbits in the Great Plains country. Its natural food is grasses and other prairie plants.

A full-grown jackrabbit may weigh from 6 to 10 pounds. The fur, buffy-gray in summer, is white in winter except for the black tips of the long ears. It is unusually fleet of foot, traveling with long leaps of from 10 to 20 feet; when alarmed it may reach a speed of 30 miles per hour or more.

The COTTONTAIL is found all over the United States, in highly populated areas as well as in wildlife preserves. This rabbit is an important small-game item for the hunter's bag. Weighing 2 to 3 pounds, it is smaller than its distant relatives, the jackrabbits, which are hares, not rabbits. The fur, dark brown mixed with gray, does not change color with the coming of winter. The cottontail does not have the speed of the jackrabbit; it depends on the protective cover of fence rows, wooded thickets, and brush patches. It feeds on a variety of vegetation, especially clover and alfalfa.

Prairie dog den that has been dug out by a badger |

The BADGER is a large, powerful member of the weasel family, ranging through the central and western part of the United States. In general impression it is yellowish gray, the head with bold white and black markings. It is shaggy-coated, heavy-bodied and short-legged. The forelegs are armed with long claws adapted for digging out the ground squirrels, mice, prairie dogs, and other small burrowing animals upon which it feeds. It frequents the prairie-dog towns of the badlands. The badger is a tough, fierce fighter.

The NORTHERN PLAINS SKUNK is the local form of the STRIPED SKUNK, which is distributed throughout the United States excluding Alaska and Hawaii. This skunk is easily recognized by the black and white markings on back and tail. Its food consists largely of small rodents, snakes, and beetles; it has a particular fondness for grasshoppers.

The striped skunk's chief defense is a musky secretion with a penetrating, disagreeable odor. This secretion is stored in glands located at the base of the tail just inside the anal opening. By muscular contraction, the skunk ejects the scent in a fine spray. The unaggressive skunk attends strictly to its own business; but if it is annoyed or alarmed, woe to the man or beast in range of its artillery!

The THIRTEEN-LINED GROUND SQUIRREL, frequently called (incorrectly) a "gopher," prefers the open country. Like the chipmunk, it feeds chiefly on seeds and grasses; crickets, grasshoppers, and other insects are also eaten. Grass seeds are a favorite food, and are stored in underground chambers to be used in the early spring after the long winter's hibernation.

The BADLANDS CHIPMUNK, often popularly described as a small edition of the tree squirrel, is not to be confused with the ground squirrels. This bright, alert little creature makes its home in burrows under rocks and tree roots. August, September, and October are busy months, for it is then that the chipmunk gathers seeds and stores them in its underground granaries. With the arrival of snow, it takes to its snug quarters for a long winter sleep. The species found in the badlands is the smallest of the chipmunks. Its pale color, blending with the badlands landscape, serves as protection from enemies. Chipmunks are common at some parking areas along the monument road, particularly those west of Norbeck Pass.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |