|

OLYMPIC National Park |

|

How To Identify Some Common Plants

Out of more than a thousand kinds of trees, shrubs, ferns, and flowering herbs on the Olympic Peninsula, 28 are described in the following paragraphs. While this is but a small fraction of the total number, they represent the most common and noticeable plants that can be identified easily.

The park is a sanctuary for all natural features, and care should be taken not to disturb, injure, or destroy trees, flowers, or other plant life.

TREES

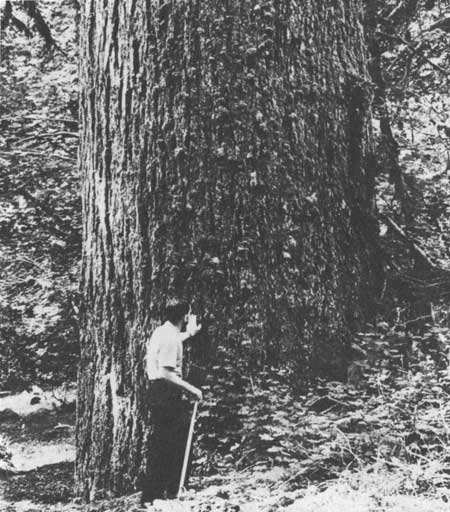

DOUGLAS-FIR (Pseudotsuga taxifolia).—The tree that gives principal distinction to the Northwest forests. Growing from sea level to 5,000 feet elevation, it is the most abundant and widespread tree on the Olympic Peninsula. Average mature trees in the virgin forests of the lowlands are 180 to 250 feet in height and 4 to 6 feet in diameter. Many are considerably larger in girth, the largest on record being 17 feet 8 inches. This tree is located in the Queets River Valley, about 3-1/2 miles by trail from the end of the road. Next to the sequoias of California the Douglas-fir is the largest tree in the forests of the Western Hemisphere.

Large Douglas-fir trees in the forest commonly have nearly cylindrical boles, clear of limbs for a hundred feet. Such trees have a reddish-brown bark which is rough with ridges and deep furrows. The cones, whether on the tree or on the ground beneath the tree, provide easy and reliable identification. They are mostly 2-1/2 to 3 inches long with 3-pointed, thin bracts protruding among the scales. The seeds are a favorite food of the Douglas squirrel.

NEXT TO THE SEQUOIAS OF CALIFORNIA, DOUGLAS-FIR IS THE GREATEST TREE IN THE FORESTS OF THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE. THIS ONE IS OVER 10 FEET IN DIAMETER. |

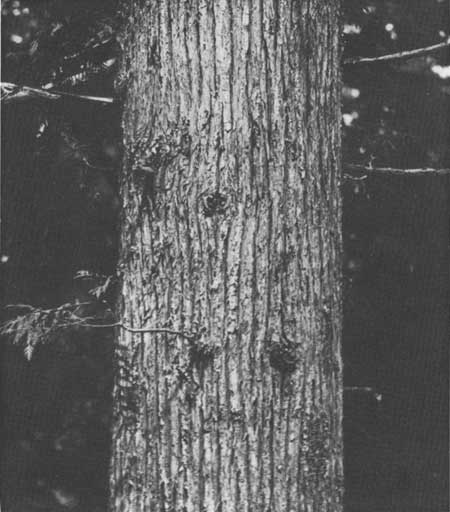

WESTERN REDCEDAR (Thuja plicata).—Grows in the valley bottoms and other moist places. Although it is mainly a lowland tree, it extends up into the Canadian Life Zone wherever conditions are favorable for its growth. Large trees in the forest average 150 to 175 feet in height and 3 to 8 feet in diameter. The largest western redcedar on record is in the park, near the road, on the north side of Lake Quinault. It is 20 feet in diameter.

WESTERN REDCEDAR. |

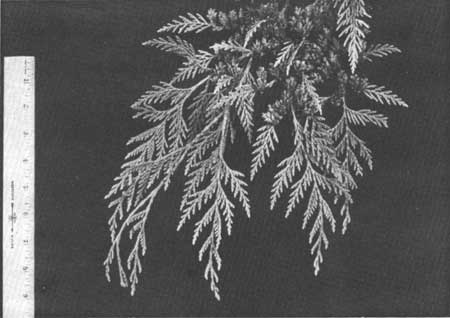

The trunk of the western redcedar commonly tapers rapidly from a swollen and sometimes fluted base. Its bark is thin, fibrous, and stringy. The foliage hangs in long, lacy sprays. It is the only tree of the lowland forests which has leaves that are tiny, overlapping scales.

WESTERN REDCEDAR. CONES ARE ABUNDANT ON SOME TREES. |

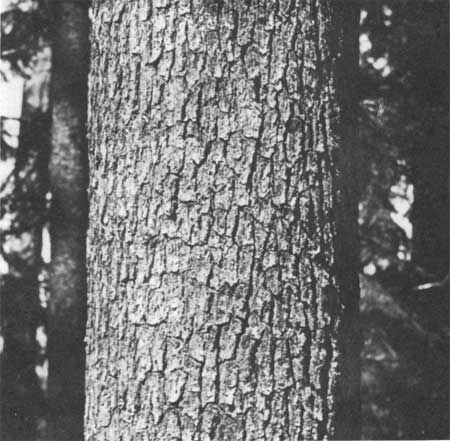

WESTERN HEMLOCK (Tsuga heterophylla).—Abundant in Northwest forests up to about 3,000 feet elevation. Large forest trees are 125 to 175 feet in height and 2 to 4 feet in diameter. The largest recorded specimen of this tree is 9 feet in diameter and is located above Enchanted Valley in the park. Western hemlock can be identified by its foliage and cones. The needles vary in length from one-fourth to nearly an inch and are pliable and round-pointed. The lacy sprays of foliage have a delicate appearance. The top shoot of the tree bends over in an arc. This is the identifying characteristic if the top of the tree can be seen. The cones, about three-fourths of an inch long, are usually abundant near the ends of the branches.

WESTERN HEMLOCK, WHICH COMBINES WITH DOUGLAS-FIR TO COMPOSE THE SOMBER CANADAN LIFE ZONE FOREST. |

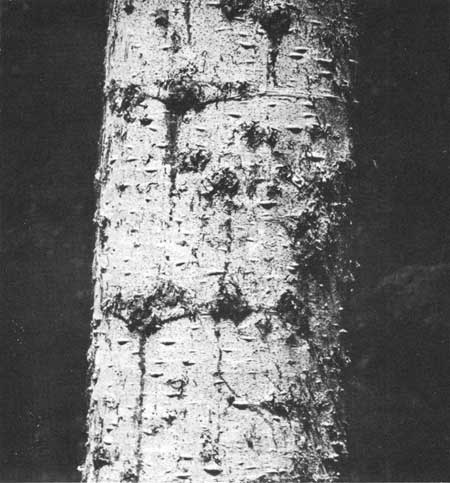

PACIFIC SILVER FIR (Abies amabilis).—A tree of middle elevations, or the Canadian Life Zone. In favorable growing sites, it attains a height of 140 to 160 feet and a diameter of 2 to 4 feet. A striking characteristic of this needle-leaved tree is its smooth, ashy-gray bark, conspicuously marked with chalky-white areas and numerous resin blisters.

PACIFIC SILVER FIR. |

ALPINE FIR (Abies lasiocarpa).—The spirelike tree. of the highest life zone, the Hudsonian. Under favorable growing conditions it reaches a height of 60 to 90 feet, but at timberline it is a twisted, stunted growth only a few feet high. Its narrow crown extends to the ground, which makes this tree particularly susceptible to crown fires. Many ridgetop areas have "silver" forests of bleached trunks of fire-killed alpine fir. The purple to gray-purple cones, 2 to 4 inches long, stand upright on the branches as in all true firs.

ALPINE FIR GROWS NEAR TIMBERLINE AND CAN BE DISTINGUISHED BY ITS SPIRELIKE SHAPE. |

ALASKA YELLOW-CEDAR (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis).—This Hudsonian Life Zone tree can easily be identified by its foliage. The slender, drooping branches and flat, weeping sprays appear to be wilted.

SITKA SPRUCE (Picea sitchensis).—A coastwise tree from Alaska to California. In the park it is common only in the rain forest on the west side. There, large trees are 125 to 225 feet in height and 3 to 8 feet in diameter. Many are 10 feet or more in diameter. The largest specimen recorded is 16 feet 3 inches in diameter and is located in the park about 4 miles above the Hoh Ranger Station. Sitka spruce and the three preceding species comprise what might be called the "big four" in Olympic forests. It is of interest that the largest recorded specimen of each of these four kinds of trees is located within the park.

SITKA SPRUCE CONES HANG IN CLUSTERS AT THE ENDS OF BRANCHES. |

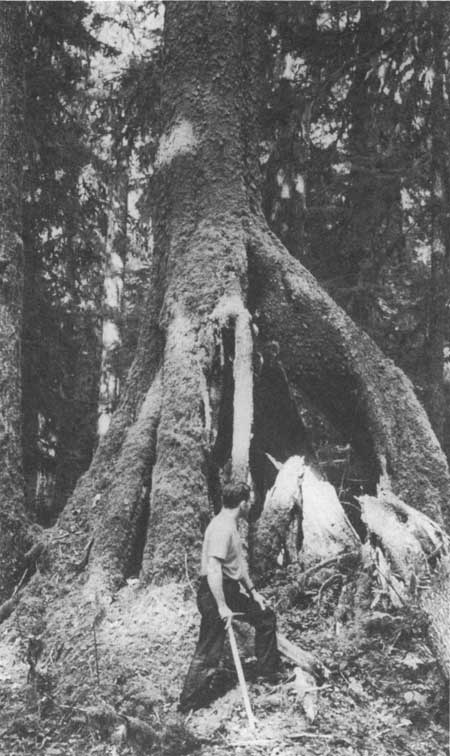

Sitka spruce can be identified by its stiff and very sharp-pointed needles. They are 1/2 to 1-1/4 inches long and extend outward from all sides of the twig. It can be distinguished from other associated trees by the thin silvery-gray to purplish-gray scales on its bark. The base of the tree is commonly enlarged because of the massive roots that grew downward from the top of a stump or large fallen tree where the seed germinated.

The leaves are of tiny, overlapping scales. This tree could be confused with the western redcedar, but as the two grow at different elevations identification should be easy.

THIS SITKA SPRUCE STARTED LIFE ON TOP OF A HIGH STUMP WHICH ROTTED AWAY AND LEFT THE GROWING TREE STANDING ON STILTLIKE ROOTS. |

PACIFIC MADRONE (Arbutus menziesii).—Tree of the lower elevations, which can be distinguished from all others by its smooth, reddish-brown trunk and branches and its shiny, leathery, broad-leaved, evergreen foliage. The bark of the trunk may be loosely scaly, peeling off in long, thin, irregular pieces. This is especially noticeable in late summer when new, light-green bark is exposed by the flaking away of the older red bark.

PACIFIC MADRONE. |

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |