|

Lava Beds National Monument |

|

|

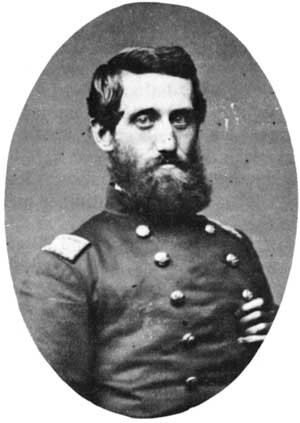

Chapter 9 EACH WARRIOR CAME FORWARD  GEN. E. C. MASON May 11-22, 1873 A draw or a victory, the fight at Sorass Lake changed the mood of the Modoc War. Davis' presence was making itself felt, and there was a new buoyancy of spirit and a quickening pace in operations. The watchdog, the Army and Navy Journal, editorialized: "General Jefferson C. Davis has not disappointed expectation in his management of the Modoc business; he has infused new life into a command demoralized by mismanagement." [1] The mood of the Modocs changed too. Unknown to the army, a fierce debate raged among the Indians following Sorass Lake. The argument centered on the conduct of that battle, particularly who was responsible for the death of Ellen's Man. Behind that was the more serious matter of the entire resistance itself. The Hot Creek band had in the beginning not wanted to get involved in the fighting. Now that the Modocs were on the run and morale was sinking, the Hot Creeks sought out Captain Jack as the man responsible for Ellen's Man's death. In the individual-oriented tribal organization of the American West, it was an easy matter for the Hot Creeks to decide to go their own way. There was little that Captain Jack or his supporters could do about it. The split came. Hooker Jim, Bogus Charley, Scarfaced Charley, Shacknasty Jim, Steamboat Frank, eight other men, and their families rode toward the mountains west of Van Brimmer's. Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Black Jim, and their group remained for the moment in the lava flow north of today's Big Sand Butte, west of Sorass Lake. [2] Davis, unaware of this development, made his plans to follow up Sorass Lake. It was at this time that he decided on his new tactics, "to move them (the troops) all into the lava-beds and form a series of bivouacks from which they could fight when opportunity offered, or could rest and take things easy, like the Indians." There would be no rest for Hasbrouck's command. As soon as he arrived at Scorpion Point, May 11, Hasbrouck sent a message to Davis saying he was sure the Modocs were located near Sandy (Big Sand) Butte. Following instructions he turned in the horses and led the same units (Battery B, Troops B and G, and the Warm Springs) south to the butte by way of Sorass Lake and Tickner Road. Camping on the plain on the south side, his men built a scattering of rock fortifications that still stand. [3] Davis also ordered Mason, at the Stronghold, to take a large command southeast across the lava beds, past Juniper Butte, and to coordinate with Hasbrouck for an attack on this Modoc position. There would be no repeating of the error of too small a patrol as in Thomas' case. Mason's command consisted of Companies B, C, and I, 21st Infantry, and Batteries A, E, G, K, and M, 4th Artillery. On April 12 the troops marched, according to Mason, "in a hollow square, covering about three quarters of a mile front." Davis wrote that this was a "scramble (it cannot be properly called a march), but that it was exceedingly creditable to the troops and commander." Mason reached his destination at three-thirty that afternoon and camped on a level area two miles north of the hill. The troops erected a large network of rock fortifications around the perimeter of the thirty acres it took to contain so large a patrol. [4] Hasbrouck and Mason were now two and a half miles apart with the butte and the supposed location of the Modocs between them. Soon after his arrival Mason discerned Indian activity "in a belt of black lava to my right and fr[ont]," that is, to the west and southwest. The next morning Hasbrouck walked over to Mason's camp and the two officers planned an attack. Either then or on the following morning, May 14, they climbed Big Sand Butte to make a visual reconnaissance of the area. They decided to delay an attack until more water could be carried to the camps. [5] An Indian scout reported to Hasbrouck on the afternoon of the 14th that he thought the Modocs had fled. First Lt. J. B. Hazelton spoke up and volunteered to take a patrol into the lava to determine the facts. He succeeded in rounding up 26 volunteers for this patrol, another indication of the changes wrought by Davis. The patrol returned, confirming that the Modocs had indeed left. Hasbrouck followed the Indians' trail to the west eight miles on May 15, finding that it left the Tickner road and bore toward Antelope Springs (Antelope Well). He gave up the pursuit and returned to Big Sand Butte to await the arrival of horses. Mason's command, very short of water, moved back to Juniper Butte. It did not stop there, for Davis directed it to return to the Stronghold and to pack up prior to moving to Gillem's Camp. The Stronghold had lost its value as a base now that the Modocs had left the lava beds. [6] Hasbrouck received his horses on the 16th and rode west from the butte the next day. About half-way between Big Sand Butte and Van Brimmer's ranch he met Captain Perry riding south with a patrol. The two exchanged information. Hasbrouck continued on to Van Brimmer's while Perry rode south toward Antelope Springs. It was their intention that on May 18 Hasbrouck would ride south and Perry would retrace his steps to the north; hopefully they would either catch the Modocs between them or at least pick up the trail. The westbound Modocs had circled around to the south of Van Brimmer's Mountain (Mount Dome) and made their way up the long ridge joining Sheep Mountain to Fairchild's (Mahogany) Mountain looming over Fairchild's ranch. [7] Hasbrouck moved south from Van Brimmer's as he had planned. Before he had gone far, his men discovered a fresh trail leading up the ridge to the west. Not at all certain this was the main trail, Hasbrouck continued on slowly while dispatching Captain Jackson and some troopers to check it out. "Very soon shots were heard," reported Hasbrouck, "and I ordered B troop and the Warm Springs to join Captain Jackson at a gallop." [8] The troopers rode hard after the Indians, firing at elusive targets, for almost eight miles toward the north. The Modocs drove their horses even harder, ducking and weaving over the irregular ridges, around knobs, and through thickets of juniper and mountain mahogany. The Indians splintered and scattered in many directions until, finally, the troopers reined in their exhausted horses. Five Indians lay dead — two men and three women. Hasbrouck hastened to point out that the women were accidentally killed because of the confusion and haste. In addition the soldiers took into custody several women, children, and horses. Then they rode slowly down to Van Brimmer's ranch. [9] Davis, possibly already aware that only part of the Modocs had been discovered, ordered the cavalry and infantry to converge on Fairchild's ranch for a final push. On May 19 Hasbrouck moved his command there from Van Brimmer's. The next day, Mason marched westward from Gillem's camp with the infantry, stopping briefly at Van Brimmer's. At the same time, Mendenhall prepared to move the artillery batteries (except B) eastward to the Peninsula camp. [10] The lava beds were emptied of troops. At Fairchild's, Hasbrouck's men mounted up on May 20 to renew the pursuit. Before they left the ranch, Fairchild told the authorities that a Modoc woman had come in saying that the Indians wanted to surrender. This development changed the situation. Davis decided that negotiations were now more pertinent than pursuit. He employed the same two women who had found Cranston's body to go up the mountain, seek out the Modocs, and inform them of the terms of surrender. [11] At this point Davis decided to relieve Gillem of his command. On May 21, Special Orders 59a pointed out that the Modocs had dispersed and that their capture would depend on detachments of mounted troops acting independently of each other. As for the foot troops, their operations "must be made to conform to the new order of things." This being the state of affairs, operations could now "more conveniently be carried on under the immediate orders of the Department Commander, while on the spot, than under those of a special commander of the expedition." This elaborate explanation concluded, "Colonel A. C. Gillem is therefore relieved from duty with this command and will proceed to Benicia Barracks," from where he had come. The timing of Gillem's relief was particularly cruel; the western band of Modocs would surrender within hours after Gillem's departure. The rest of Special Order No. 59 restored Frank Wheaton to command of the expedition. This was Davis' and the army's way of saying that Wheaton had not been responsible for the earlier disasters. Although Wheaton's reputation glowed again, there was no mistaking Davis' direct command of future operations. [12] John Fairchild and his wife went up the mountain on May 22 and after a short parley came down again with 63 Modoc men, women, and children. "'Here they come!' was the cry that . . . brought every person, citizen, and soldier, old and young, to his feet." The excited crowd pressed forward to witness the surrender, "First came Mr. Blair, the manager of Fairchild's rancho, mounted; fifty yards behind him was Mrs. Fairchild, and further still twelve Modoc bucks, with their squaws and pappooses [sic]." The procession barely moved; here and there gaunt ponies "seemed scarcely able to bear the women and children who were literally piled upon them." A hush fell over the waiting crowd as the party approached: "The Modocs said nothing. No one approached them until General Davis came forward. He met the procession fifty paces from the house, and was formally introduced to Bogus Charley." Then each warrior came forward, greeted Davis, and laid his rifle at the colonel's feet. Davis spoke to them, demanding all their weapons and warning against attempts to escape. He directed them to a clump of trees on the opposite side of Cottonwood Creek where they were to camp. "At this point the tailings of the crowd came in," wrote a witness. "There were half-naked children, aged squaws who could scarcely hobble, blind, lame, halt, bony, the scum of the tribe." Bogus Charley, who spoke English, gave Colonel Davis the details of the split with Captain Jack. He also told him, erroneously, that Boston Charley had been killed. Another warrior was not with the group — Hooker Jim, "the Lost river murderer." But, shortly, Hooker Jim came in alone, and he too surrendered. Two days later on May 24, Mason's infantry came up from Van Brimmer's to take charge of the prisoners-of-war. The cavalry had one more job to do — capture Captain Jack. Colonel Davis wired General Schofield, "I hope to end the Modoc War soon." [13]

|

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Modoc War ©1971, Argus Books thompson/chap9.htm — 11-Nov-2002 | ||