|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 7:

THE LURE OF GOLD (continued)

Resurrection River Mining Sites

As noted in Chapter 3, Russians had occasionally traveled up and down the Kenai River drainage during the early and mid-nineteenth century, and in 1850-51 mining engineer Peter Doroshin headed a 14-man party that ascended the drainage and scouted for minerals in the area just west of Kenai Lake. The Russian party found gold seemingly everywhere it looked, but the quantities were insufficient to warrant further exploration. [184] Some Americans, however, believed that the area held an untapped gold reserve. A 1921 issue of the Seward Gateway described the long-rumored gold:

Shortly before the acquisition of the Territory by the United States government, the Russians had discovered placer gold in interesting quantities on the high ridges of Resurrection River on the right [west] limit, but owing to the change in ownership and resulting circumstances, the prospecting in this locality was discontinued. Following down to our day, there has even been a whispering amongst the out-of-door men like unto a legend that placer gold was found by the Russians on the high reaches of Resurrection River. [185]

No one, however, responded to the siren song until after the turn of the century. Two brothers–William L. and B. F. Redman–were the first known prospectors in the Resurrection River drainage. William L. Redman, an experienced quartz miner, moved from Bellingham, Washington, to Seward in 1907. He and several partners spent the next two years prospecting along the east side of Resurrection Bay or in the vicinity of Kenai Lake. [186]

In 1909, B. F. Redman joined his brother, and the two headed toward the upper reaches of the Resurrection River in order to investigate possible mining sites and establish claims. They first traveled to present-day Redman Creek, and on September 3 they established three quartz claims at the head of the creek. They may have remained at the site that winter; the following spring, however, the brothers vowed their intention to prospect "the upper reaches of Resurrection River," and before long they ventured north to Placer Creek. In August 1910 they "made an important strike" there and staked Log Cabin Placer Claim Nos. 1 through 8. By October of that year, the property (in the words of the local press) "bids fair to become one of the big mines of this peninsula," with assays "of better than $12 per ton in gold." "Creditable reports" at the time noted that the mine "will soon be opened" as a commercial venture. The two "Redman prospects" were still viable during the summer of 1911, when U.S. Geological Survey topographer R. H. Sargent visited the area; they were the only mineral deposits located in the Resurrection River valley at that time. [187]

Despite that optimism, the Redmans worked their claims for only a short time. In January 1912, B. F. Redman relinquished all of his remaining mining properties (including the eight Placer Creek claims) to his brother, and just two days later, W. L. Redman agreed to sell all of his Kenai Peninsula claims to J. D. Meenach of Seattle. Meenach, however, was unable to complete the transaction and the properties remained with Redman. Before long, however, William Redman died, and in March 1913 his widow, May Redman, sold three of the claims–Log Cabin Placer Claim Nos. 1 through 3–for $100. The purchasers were Seward residents John Dubreuil and Frank Winchester. Winchester apparently lost interest in the claim shortly after purchasing it. [188]

John Dubreuil, the new claim owner, had been born in Canada in 1863. He was a relative pioneer to the area; he and his wife, who was five years his senior, had moved to Seward just two years after the town's founding. In 1905, he prospected along the eastern side of Resurrection Bay. The following year, he and his wife built and opened a small Seward hotel. They continued to do so until September 1908, when his wife died of a stroke. The following year, both Dubreuil and William Redman were serving as volunteer firemen; furthermore, Dubreuil made no secret of his desire to abandon the hotel business in favor of mining. So it is not surprising that Dubreuil, in March 1913, purchased several of his late friend's mining claims. [189]

During the next several years, Dubreuil apparently spent little time on his claims. He did, however, retain an interest in them, and during the fall of 1919, when local residents petitioned the Alaska Road Commission to build a short spur road up the Resurrection River valley from Seward (see Chapter 5), Dubreuil was an active supporter (although not an instigator) of that effort. At the time, others were also developing mining properties in the Resurrection River valley. They included Charles A. Tecklenberg, who also had claims near Hope and a fleeting interest in the Sonny Fox Mine at Nuka Bay; the Adams Company, represented by John and Charles Adams; and the Stotko Company, represented by J. P. Stotko. Anton Eide, a Road Commission official based in Seward, noted that the local mining district consisted of "some claims up there in various stages of development." [190]

Perhaps intrigued by the road proposal, Dubreuil returned to his claims, and during the winter of 1920-21 an 18-foot tunnel and 66-foot raise was driven on his property, which was located "at the falls of the Placer River." Dubreuil constructed the tunnel so as to divert the stream at the top of the falls; this diversion caused the stream to pour out of an adjacent rock wall. The following spring, Dubreuil began to sluice the former creek bed and soon recovered "a substantial quantity of placer gold." When he returned to Seward, he exhibited "large samples" of the coarse, dark gold and noted that although the site "discloses an ideal hydraulic proposition," it would probably continue to be operated as a "most feasible hand mining proposition." [191]

Encouraged by his find, Dubreuil continued his work at the site, and by 1924 he had added two new claims–Log Cabin Placer Claim Nos. 4 and 5–to his original three. (As noted above, the Redman brothers had originally established claims with this name in 1909 or 1910. It is not known if the two new claims were located in the same place as the former ones.) Dubreuil's claim was apparently quite successful; John Brody, a former district ranger with Chugach National Forest, recalled that "some ambitious men ... took out about 25 to 40 thousand in gold" from the site. [192] The site was sufficiently significant that the U.S. Geological Survey, in 1924, noted that Resurrection River was one of several "small producers in the Kenai District." The optimistic Seward Gateway noted that the river valley, in 1925, was "rich in placer and quartz workings." (Dubreuil's property was undoubtedly productive; so far as is known, however, other area prospectors were unable to commercially develop their operations.) Dubreuil himself most likely abandoned the site during the mid- to late 1920s; he died during the 1930s.

Before long, William "Bill" Bryan became interested in the area. Bryan, who was in charge of the Resurrection Bay Lumber Company sawmill at the mouth of Fourth of July Creek, purchased various properties and claims in the Seward area. On December 5, 1932, he and two partners–Oliver Bryan (his brother) and longshoreman Lindsay "Happy" Ratchford–discovered and located three mining claims. These claims, known as Falls Claim Nos. 1 through 3, were on Placer Creek and situated "14 miles from the Rail Road up the Resurrection River." They were probably located at or near the site of the Redman-Dubreuil claims. [193] How long the claims may have been retained is unknown; they may have been abandoned just a few years later, or they may have been retained until October 1944 when Bill Bryan, the last of the trio still living, disappeared under mysterious circumstances. The three apparently conducted development work, but commercial production never took place. [194]

No sooner had Bryan disappeared than new interest arose in the area. Herbert Smith, who was probably nicknamed "Whitey" Smith, had been using trapping cabins, on the Resurrection River's east side, since the 1930s. (In 1939 he had requested a U.S. Forest Service permit to use a trapping cabin just south of the Boulder Creek mouth. Although he eventually abandoned that site, he returned to the area in 1945 and requested a second permit for a trapping cabin two miles to the south, at the mouth of Martin Creek.) Smith and Bryan knew each other; when Bryan disappeared, in fact, the local newspaper noted that Bryan, at first, was "thought to be up the Resurrection River with Whitey Smith, who has a cabin about 18 miles up the river from Seward." [195]

Smith apparently moved to claim the Placer Creek property soon after Bryan's disappearance. No record has surfaced regarding his locating the property, but he, together with George Lesko and possibly Foss Wright Sargent, appear to have constructed a cabin on the property in 1945 or 1946. (George Lesko and his wife Myra Lesko, and Foss Sargent and his wife Mary "Irene" Sargent, were all recent migrants to Seward. If the values placed on quit-claims are any indication, George Lesko may have helped Smith construct the cabin but Sargent may have joined the partnership at a later date.)

|

| Foss Wright Sargent, a recent migrant to Seward, may havfe helped built the Placer Creek cabin. He was one of a trio of men who owned the cabin from the late 1940s until 1953. NPS photo. |

The three retained an interest in the cabin until 1950. Seward resident George Black bought out Bert Smith's interest in the property that January. During the spring of 1953, Black purchased the interests of Sargent and Lesko. Black paid a total of $210 for the cabin. Neither Black nor the trio that preceded him, it should be noted, were interested in the area's mining claims; instead, they were interested in the "cabin and the surrounding grounds" for their trapping or homesteading possibilities. [196] Black, the cabin's owner after 1953, remained in Seward for years afterward. Nothing is known, however, about whether he spent much time at his cabin. Before long he abandoned it. During subsequent years, as graffiti on the cabin's walls attest, other Seward residents used the cabin from time to time. The Bureau of Land Management recognized the cabin's cultural importance following a June 1978 visit by archeologist John Beck, but the site was still unclaimed public land when President Jimmy Carter proclaimed Kenai Fjords National Monument in December 1978. [197]

During the summer of 1983, archeologist Georgeanne Reynolds led a reconnaissance of the Resurrection Valley's west side. Central to her survey was an investigation of the lower Redman and Placer Creek drainages. The survey uncovered evidence of four area cabins. On the south bank of Redman Creek, on the western edge of the valley, the team uncovered the ruins of a 16' x 17' cabin. Hidden in the underbrush, the extant walls were two to three logs high. Reynolds noted that a 1915 report on the area, which was based on 1909 fieldwork, described a placer mine in the vicinity but did not describe a cabin. Reynolds therefore concluded that the cabin "most likely dates to the 1920's mining era due to its state of preservation and all the similarities with the other mining aged cabins located this summer." She further suggested, on the basis of site evidence, that the cabin may have been a short-term or intermittent occupation site. [198]

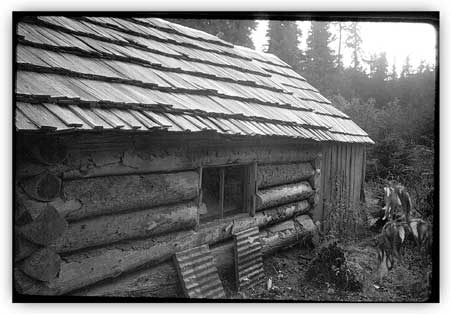

On Placer Creek, Reynolds and her crew found the remains of three cabins. The most intact cabin, the so-called Placer Creek cabin, was just south of the creek and one-half mile west of the creek's confluence with the Resurrection River. It was the only standing historic structure in the valley. The dimension of the one-room cabin, with an adjacent portico, was 25' x 15'. Reynolds estimated that the cabin was built in 1945 or 1946. She noted several remarkable architectural features:

The building was carefully constructed as a major residence and multi-purpose (i.e., mining and trapping) base of operations. The logs are well laid and tightly fitted, utilizing a modified saddle notch technique. The hand split shingle roof is also carefully crafted and is a rarity in this part of Alaska because of the difficulty in finding clear and straight grained wood suitable for bolts. Another unusual feature is the portico on the east end of the structure which functioned as a shed. [199]

The cabin, Reynolds noted, was being converted during the summer of 1983 into a backcountry public use cabin. That summer the roof was reshingled, tin was laid around the stovepipe, and new floor joists were laid. Five years later, a new stovepipe was installed. [200>] In 1997, the entire cabin was restored. The cabin has not yet been evaluated for eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places.

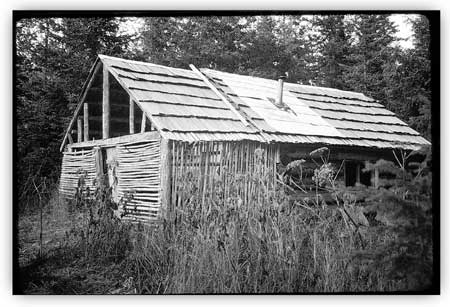

Just 470 feet upstream from the Placer Creek Cabin, the team found a cabin ruin. Reynolds noted that the logs were stacked three or four high in the corners of the 12' x 13' structure; the center of the walls, however, were lower. Based on a site survey, Reynolds estimated that the site "evidently predates Placer Creek Cabin due to its advanced state of deterioration." (She noted elsewhere that the cabin was "likely much older" than the Placer Creek Cabin, but she did not speculate as to the cabin's age.) The lack of a dump, the lack of artifacts under the collapsed roof, and the small size of the foundation led her to conclude that the cabin had witnessed only short-term use. [201]

The team located the remains of a third cabin in the Placer Creek drainage on the creek's north side, almost directly across from the Placer Creek Cabin. Reynolds noted that the cabin, although in a ruined state, was relatively intact in comparison to both the Redman Creek ruin and the 12' x 13' cabin ruin on the south side of Placer Creek. This cabin, which had dimensions of 13' x 14', featured walls that were between four and five logs high, and the surrounding clearing had not regrown as much as the other two ruins. Based on the large amount of mining-related debris around the site, Reynolds estimated that the cabin "probably dates to the mining days of the 1920's and early 1930's." She further noted that the cabin was occupied for a longer period of time than the 12' x 13' ruin on the south side of Placer Creek. [202]

Inasmuch as Reynolds did little historical research in conjunction with her archeological survey, she was able to provide only rough estimates on the age of the various Resurrection River valley cabins. In 1997, however, NPS intern Mary Tidlow prepared a draft Historic Structures Report for the Placer Creek cabin; as part of her research, she extracted sufficient historical documentation to provide a historical context to each of the cabins that Reynolds had identified. Her history noted, for example, that the Redman brothers' prospecting in 1909 and 1910 was the only known historical activity along Redman Creek. That knowledge, combined with the deteriorated condition of the Redman Creek cabin ruin, caused Tidlow to conclude that the Redmans built the Redman Creek cabin; this date is consistent with verbiage in the 1915 USGS report, which described mining activity along the creek in 1909.

Tidlow, on the basis of her research, also helped pinpoint the history of the various Placer Creek cabins. She noted, for example, that the Redman brothers also built the 12' x 13' cabin on the creek's south side in either 1909 or 1910. The brothers abandoned the cabin shortly after it was constructed, but it apparently later served as the occasional residence of John Dubreuil, who owned several area mineral claims from 1913 to the mid-1920s. The cabin on the north side of Placer Creek, which was in better shape than the 12' x 13' cabin, probably dates from the 1930s; based on her research, Tidlow noted that the cabin was probably built by William "Bill" Bryan, Oliver Bryan, and Lindsay "Happy" Ratchford. Herbert "Whitey" Smith and George Lesko, possibly assisted by Foss Wright Sargent, probably built the so-called Placer Creek Cabin in either 1945 or 1946. This cabin is still standing; it is, in fact, the only standing historical structure in Kenai Fjords National Park. [203]

Little is known about the various historic cabins east of the Resurrection River, all of which are administered by the U.S. Forest Service. As noted above, "Whitey" Smith had permits for two "trapping cabins" during the 1939-1945 period. One was near the mouth of Boulder Creek (specifically, within 132 feet of the east bank of the Resurrection River and "approximately 400 yards from Boulder Creek"), while the other was at the "junction of Martin Creek and Resurrection River." [204] Inasmuch as historical mining claims were established along Martin Creek (and perhaps Boulder Creek as well), it is probable that both of these cabins were built prior to the late 1930s. Both were built to support either mining or trapping activities. The condition of the two cabins is unknown.

Two other historic cabins also appear to have been built east of the Resurrection River. One is located near the river, midway between Martin and Boulder creeks; the other is just three-quarters of a mile north of the Resurrection River vehicle bridge. Archeologist John Beck noted both cabins during a June 1978 overflight. He was not able to visit either cabin on the ground. On the basis of his aerial observation, however, he noted that the two cabins were still standing; moreover, they "have hand split shingle roofs and could conceivably have been constructed by the same individual(s)" that constructed the Placer Creek cabin. That assumption, however, was challenged in 1984, when U.S. Forest Service archeologist Jonathan Lothrop surveyed the area around the proposed Boulder Creek Recreation Cabin. During that survey, he located the cabin midway between Martin and Boulder creeks. He found it "in a state of advanced decay, with the original corrugated sheet metal roof collapsed and the four walls still standing, but missing one or two of the upper log courses." He concluded that the structure did not qualify for the National Register of Historic Places. The other cabin has not yet been subject to a detailed survey; a Forest Service official, however, noted that the cabin had "pretty well melted down" by the mid-1990s. [205] Historical details about both cabins are entirely lacking.

|

| The Placer Creek Cabin, built in 1945 or 1946, is located in the Resurrection River valley north of Exit Glacier. The only standing historic building in the park, it was photographed in November 1992. NPS photo. |

|

| The Placer Creek Cabin, as seen in November 1992. NPS photo. |

kefj/hrs/hrs7f.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002