|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 6:

LIVING OFF THE LAND AND SEA (continued)

Harbor Seal Harvesting Prior to

1960

The southern Kenai Peninsula coastline is generally rocky and precipitous with numerous deep-water fjords. These conditions are highly attractive to harbor seal populations, and seals are particularly drawn to areas near calving tidewater glaciers. Not surprisingly, therefore, there are "high densities" of harbor seals in Resurrection Bay, Aialik Bay, Holgate Arm, Harris Bay, the Twin Islands (near Aligo Point), McCarty Fjord, Moonlight Bay, Beauty Bay, and the west side of Nuka Island. Several hundred seals live in the vicinity of each of the area's tidewater glaciers, and a biologist in a 1976 survey counted 2,233 harbor seals in park waters. As noted in the paragraphs below, many of these areas have witnessed seal harvests over the years, but so far as is known, these harvests have had no appreciable effects on the long-term viability of harbor seal populations. [70]

During the early twentieth century, the seals in the present-day park were for the most part ignored. Natives from English Bay and Port Graham did not, as a rule, harvest seals as part of their subsistence lifestyle, and the few non-Native miners and fishermen who lived in and around the present park had little interest in them.

That situation changed in 1927, when the territorial legislature passed a bill creating a bounty for hair seals. [71] That situation grew out of a general attitude among Alaska residents, many of whom hunted or fished. Alaskans, along with Lower 48 residents at the time, drew a sharp distinction between "desirable" (edible or commercially valuable) and "undesirable" game and fish species, and few Alaskans had qualms about manipulating game or fish populations in order to increase the harvests of desirable species. As a result of those attitudes, the territorial legislature passed a law in 1915 creating a bounty on wolves, because of their effect on caribou populations. Two years later it instituted a bounty on bald eagles, because it was thought that salmon constituted a major portion of their diet. Other laws subject to bounty were coyotes (beginning in 1929), Dolly Varden trout (1933), and wolverines (1953). [72]

Agitation to pass a hair seal bounty apparently began in 1925, when a government study concluded that the diet of hair seals, which lived near the coast, was rich in salmon. (But fur seals, that inhabited deeper waters, were less prone to ingest them.) That study reinforced the attitudes of many Alaskans; one wildlife agent noted that "according to popular belief, there were anywhere up to a million sea lions and double that number of harbor seals in Alaskan waters, each one making catches of food greater than the average fisherman could produce." [73] Perhaps in response to the study, Alaska state senators John W. Dunn and Charles W. Brown (both on the Fisheries, Game and Agriculture Committee) introduced a measure on March 28, 1927 mandating a $2 bounty. On April 20, the bill unanimously passed the Senate. Soon afterward it sailed through the House, and on May 3, Governor George Parks approved the bill and it immediately went into effect. [74] The bounty was applicable for all seals harvested "adjacent to the southern coast of Alaska and east of the 152nd meridian," which included southeastern Alaska and all of south central Alaska east of Cook Inlet. In order to obtain the bounty, hunters were asked to show the face of the seal skin, including both eye holes and both ears, to any U.S. Commissioner, postmaster, or notary public. They also had to fill out a certificate showing where, when and how the animals were killed. [75]

Alaskans responded to the law with a modest degree of enthusiasm. For the next twenty years, the number of seals harvested each year seldom exceeded ten thousand per year. Several reasons accounted for the limited amount of activity. First, both seal meat and seal hides had little value. Second, the bounty was insufficient to provide a living to anyone but the most dedicated hunters. Finally, seal hunting required both a rugged, sea-going boat and a skiff, articles that most residents did not possess. As a result, a federal official noted in 1946 that

There is no organized hunting of these sea mammals by bounty hunters; they are generally taken coincidentally with fishing operations or by Natives seeking their pelts for the manufacture of moccasins & parkas, both of which items are sold in considerable quantity to tourists.

He further noted that the number of pelts harvested was negatively related to the health of the economy; that is, when the economy was poor the annual pelt harvest tended to rise, and vice-versa. [76]

The Alaska legislature was not particularly concerned, in its bounty bill, with seal predations on the Kenai Peninsula; most of the commercial fishing took place along the peninsula's western coastline, while the only significant seal populations lived along the southern coast. Even so, peninsula residents were quick to take advantage of the new law. Several Port Graham and English Bay Natives found new sources of wintertime cash by collecting seal bounties. In Seldovia, seal hunting was also active. Graduate student Richard Bishop concluded that the activity was "kind of universal along the coast." There were "a number" of coastal seal hunters, who together comprised "a steady, small-scale industry." It is not known, however, if residents of English Bay, Port Graham, or Seldovia ever hunted seals within the present park boundaries. [77]

Non-natives living in Seward also responded to the law and began hunting seals in the various bays and fjords southwest of town. According to Richard Bishop, who spoke to several seal hunters during the early 1960s as part of a graduate research project, the activity was "a long standing practice" both in Aialik Bay and in the East Arm of Nuka Bay. [78]

Perhaps the most avid local seal hunter was Pete Kesselring. Although he earned money as a game guide and also hunted and trapped for food, seal hunting was an important part of Kesselring's income for a number of years. When he began hunting is uncertain, perhaps as early as the mid-1930s, but by the mid-1940s he was making yearly expeditions to the various bays and fjords south of town; favorite locations were Aialik and Harris bays. [79]

|

| Longtime Seward seal hunter Pete Kesselring at his Aialik Bay seal-hunting camp, 1955. The camp was set up in early May, just above the high tide line. Alaska Sportsman, August 1956, 18. |

|

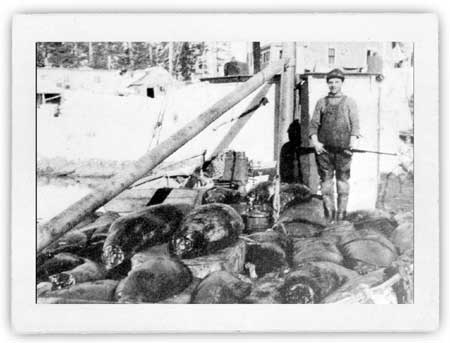

| Pete Kesselring processing a newly-killed harbor seal. Alaska Sportsman, August 1956, 21. |

Another seal hunter was Bernard W. (Bill) Younker, who arrived in Seward in the early 1940s and began hunting seals soon afterward. Younker, who was also a big game guide, hunted seals each year; as he noted in an Alaska Sportsman article, he typically left Seward in early May and returned in mid-July, when the seals began migrating away from the fjords. A 1955 hunt with Pete Kesselring, to Aialik Bay and Holgate Glacier, resulted in a harvest of almost 800 seals; they earned money from both the bounty and from the sale of seal livers (to markets in Seward) and hides. He noted that "we're bounty hunters, and although [the bounty] isn't going to make millionaires out of us, along with a few ‘bucks' for livers and hides we manage to keep beans in the pot, and we have a lot of fun doing it." [80]

|

| Bill Younker hunted for harbor seals during the 1950s. In July 1957, he filed for the Aialik Bay homestead that was later awared to William F. Hart, Jr. Alaska Sportsman, August 1956, 21. |

Other local residents who commonly hunted seals prior to 1960 were Pete Sather, the Nuka Island fox farmer, who (as noted above) often harvested seals for fox food, and Bob Evans, the homesteader who occupied the cabin on the east side of McCarty Fjord during the 1930s and early 1940s. William F. Hart, who homesteaded the site just north of Coleman Bay (near Aialik Glacier) in 1959, hoped to use the site to hunt seals; there is, however, no evidence that he ever did so. [81] Longtime resident Seward Shea noted that Harold Cedar, Cecil Torgramson, Hank George and Ralph Grosvold–the latter a Kodiak resident–also hunted seals during this period. Shea also felt that "perhaps 10 to 20" others (beyond the four just mentioned) hunted seals, although some of that number hunted in areas southeast of town, such as Bainbridge Passage. [82]

Some locals, with the help of Pete Sather, engaged in wintertime seal hunting. As Josephine Sather explained in 1946,

In the winter, when work was scarce, some men would go seal hunting for the bounty.... To hunt seals you need a power boat to get to their grounds, and a skiff. Since few bounty hunters had either, [Pete] would take them and their camping outfits to some glacier on salt water; let them use one of our skiffs; and carry their mail and supplies to them. In return, they would give us the seals after they had been scalped. We often obtained as many as two hundred seals in a season. In the winter the seals are extremely fat, the largest of them having as much fat on their bodies as a good, fat hog. [83]

|

| In order to feed their foxes, the Sathers and other fur farmers sometimes relied on bounty hunters to provide them with seal carcasses. Alaska Sportsman, September 1946, 19. |

Alaska's legislature, as time went on, evidently felt that the bounty was an increasingly effective seal management tool. In order to increase the harvest, it increased the bounty in 1939 from $2 to $3; ten years later, it was briefly raised to $6 before being reduced again to $3 in 1951. The legislature also toyed with the area in which seals were bountied. In 1949, for example, the boundaries were extended to cover the entire territory; in 1951, it was reduced to include the former (1927) boundaries, plus Bristol Bay, Norton Sound and Kotzebue Sound; and in 1962, the boundaries were once again extended to cover all of Alaska's coastline. Throughout this period, the bounty remained in effect for seals harvested off the Kenai Peninsula. [84]

The legislature was bullish on the bounty program, both in response to citizen concerns and because its members felt that salmon constituted an important part of the harbor seals' diet. Those assumptions, however, began to slowly unravel during the 1940s and 1950s. Of the six species for which the legislature offered bounties, two species had their bounties eliminated during this period: the Dolly Varden in 1941 and the bald eagle in 1953. [85]

Meanwhile, a growing body of science was questioning the scientific assumptions behind the harbor seal bounty. Acting on a March 1944 complaint "about the seal herd at Cordova," the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service decided to study the feeding habits of both seals and sea lions in Alaskan waters. Frank W. Hynes, who headed the agency's Alaska office, had heard that "the Seward area and to the westward" had major sea lion depredation areas, so he contacted Roy L. Cole, the longtime skipper of the patrol boat Teal about the matter. Cole, in response, urged that the proposed study take place at the Seal Rocks, near Seward, inasmuch as the sea lions there were relatively easy to study. In the spring of 1945, therefore, Hynes dispatched Ralph W. Imler to the field. Imler, as suggested, visited the Seal Rocks and estimated that 400 to 500 sea lions inhabited them, but owing to rough seas, he was unable to work there without a large boat. Imler spent much of the summer on the study, which was conducted at the Copper River mouth, at the Chiswell Islands, and elsewhere. By the spring of 1946 the study was complete; its conclusions debunked the prevailing attitudes by showing that salmon were a minor part of the harbor seals' diet. Most of their diet consisted of "oolachon" [eulachon] and other species. According to one agency official, "it is not believed that the hair seal is a factor to be concerned about in the conservation of the salmon runs. No federal control measures are believed necessary." [86]

An agency official followed up Imler's study by observing harbor seal predations at the Stikine River mouth, near Wrangell. He concluded that the present bounty should be continued and that seals were "a costly nuisance" to several of the area's gill net fishermen. Losses here, as well as at the Taku and Copper River mouths, were estimated at "from 2 to 10 per cent of the fish caught [by commercial fishers] or even more." [87]

The Alaska Territorial Department of Fisheries, which was organized in the late 1940s, recognized that the bounty–even when set at $6 per seal, as it was in 1949 and 1950–was an ineffective way to control seal populations and thus reduce damage to the territory's fish runs. It therefore responded to area-specific complaints by instituting a small-scale program of seal control. In 1951, a summertime employee was stationed at the mouth of both the Stikine and Copper rivers, where rifles were used to dispatch harbor seals. The program was judged successful. The following year employees returned to those sites, and a third employee was stationed at the mouth of the Taku River. The program continued until 1958; at the end of that season, officials proudly noted that since its inception 36,163 harbor seals had been killed: 30,250 at the Copper River, 4,999 at the Stikine River, and 914 at the Taku River. [88]

Territorial officials never had any illusions that hired hunters would eliminate the "seal problem" in those areas. They were glad to note, however, that they had made a "large impact" on certain of those populations. By 1957, however, they readily admitted that the program might have been misdirected and that "seals eat more than just salmon." They agreed that the problem was complicated and that it needed further study. [89]

During the 1958 season, territorial biologists did indeed study the problem in greater depth. They found that while a number of seal that were harvested from the Copper, Taku, and Stikine River mouths had salmon in their stomachs, none of those caught elsewhere in the territory showed evidence of salmon ingestion. This conclusion cast a strong doubt on the value of a bounty as a territory-wide management tool. The agency further concluded that "the bounty system is not providing adequate protection from depredations by ... seals, and that planned programs [such as those at the three river mouths] can do the job with smaller expenditures." "In other areas," a report noted, "seals may actually be a benefit to the salmon fishery." The report made the somewhat startling conclusion that "hair seals also have value in themselves and should not be destroyed where it is unnecessary." [90] The implication was clear; the bounty system should be eliminated, and area-specific control methods were the only ones that worked. The year 1958, however, brought congressional passage of a statehood bill. Once statehood was attained, site-specific predator control at the three river mouths was abandoned and the $3 harbor seal bounty remained in place.

kefj/hrs/hrs6d.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002