|

Katmai

Tourism in Katmai Country |

|

CHAPTER 7:

COMMERCIAL LICENSES AND PERMITS

In the late 1970s, Katmai began to witness increased visitation by commercial operators based outside of the park. In order to regulate the usage of these operators, the Alaska Area Office (later the Alaska Regional Office) devised the Commercial Use License system, which was later adopted on a nationwide basis. Since the implementation of that system, the popularity of CUL operations has dramatically expanded; at the present time more than 60 operators per year visit Katmai, primarily for sport fishing purposes. Along American Creek, usage became so intense that both guides and park personnel demanded a change, and in 1986 a Limited Commercial Permit system was implemented. Other drainages have been considered for such permits. Within Katmai National Preserve, at the north end of the park unit, hunting has taken place for decades. Guides who used the area were required to obtain CULs in the early 1980s; after the dissolution of the state-imposed system of guide areas in 1988, the NPS began to issue commercial permits based on historical usage patterns.

Although the major concession facilities and inholdings account for most of the park's commercial improvements, thousands of people who visit the park each year arrange their trips with outside operators. Scores of commercial operations today utilize Katmai lands, a majority of which specialize in fishing trips. But many other activities are also offered. These include water sports such as float trips, kayaking and canoeing; overland pursuits such as hiking, backpacking, camping and mountaineering; and more relaxed activities such as photography and aerial sightseeing. Visitors carrying on these activities crowd the major rivers, lakes and trails and peaks each summer, and an intrepid few come during winter time as well.

Most of the guiding activities are only lightly supervised by the National Park Service. The agency encourages the use of these public lands as long as such use does not detract from the resource or from the experience of the visitors involved. During the last decade, most of Katmai's guiding activities have been sanctioned through the mechanism of Commercial Use Licenses (CULs). Only in two instances—sportfishing along one of the park's water courses, and sport hunting within the preserve—has it been necessary to institute a stronger regulatory mechanism. This chapter will first discuss the evolution and development of the CUL system, followed by a discussion of the park's two permit systems.

|

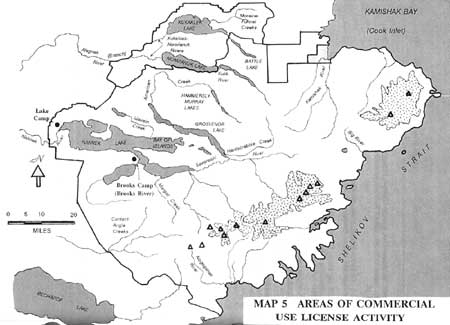

| Map 5. Areas of Commercial Use License Activity (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Early Katmai Fishing Guides

The explosive growth of guiding activities in the park is of a recent vintage. Before the mid-1960s, the concessioner was the only entity which carried on commercial activities in the park, and before the mid-1970s few fishermen or other recreationists knew about, or participated in, vacations that took them far from the lodge where they stayed. The organized outdoor tour is also a phenomenon which, in Alaska at least, was seldom found before the 1980s.

Fly-in fishing, despite its recent surge in popularity, is a long-established recreational practice in the Katmai area. The first fly-in fishermen, in fact, were the established concessioners. Fishermen based at Brooks Camp began to charter planes to remote spots in the monument as early as the early 1950s. Most flew with NCA pilot John Walatka, but King Salmon pilot Edwin Seiler was also allowed to advertise at the camp. [1] Grosvenor Camp guests who wanted to fish elsewhere normally boated to their destination, but Kulik and Nonvianuk camps, as well as Enchanted Lake Lodge, became base camps for fly-in fishing by the mid-1970s. [2] These lodges, the acknowledged pioneers in fishing the more remote Katmai streams, continue to provide these services to their guests. [3]

The advent of trips into Katmai for guests based outside the park, however, is a relatively recent development. [4] The first known trips of this nature, aside from those guided by Edwin Seiler, took place during the early 1970s, and most if not all carried fishermen in from King Salmon. The first known fishing guide was John Prestage, whose Prestage's Fishing Lodge operated in the area through the mid-1980s. Most of the other early guides also hailed from King Salmon; they took visitors into the park via Lake Camp, and limited their operations to Naknek Lake and Naknek River. Early King Salmon guides included Dean Paddock, operator of Last Frontier Lodge; Joe Klutsch, whose Katmai Guide Service is still active; Jack Wood, owner of Wood's Alaska Sport Fishing, and active since the early 1970s; Chuck Wood, whose Wood-Z-Lodge was the largest outfit to take visitors into the monument; and Mike Morrison, of Morrison's Guide Service, who began guiding about 1978. [5]

There were also, in those pre-ANILCA days, several guides who came into the monument from points outside of King Salmon. They flew into Katmai, and helped pioneer many drainages outside of the Naknek Lake system. Bud and Mike Branham, whose Kokhanok Lodge had been in operation since 1949, were two early guides. Ray Loesche, who was a hunting guide in the area in the 1960s, took visitors to the Kamishak and Big Rivers before 1972. He was the first fly-in guide to those drainages. He was also one of the earliest guides to visit Battle River as well as Moraine, Funnel and Nanuktuk creeks, having visited each of them by 1968. By 1980 several guides, promoting fishing and float trips, were already active along Nonvianuk River; in order to monitor their activities, the NPS dispatched a ranger to the lake outlet. [6]

Establishment of the Commercial Use

License

The National Park Service was becoming increasingly aware that the number of outside guides was growing. They were doubtless aware of the various fishing guides based in King Salmon, but they were probably less aware of the various fly-in fishermen who visited the more remote parts of the park, or of any companies engaged in backpacking, kayaking, or other activities.

The NPS, at Katmai, had some control over the established concessioner through the various stipulations of the concessions contract. But it was not able to regulate day-use visitors. As long as the number of guiding companies which used Katmai remained small, the resource was not being significantly impacted. Through the mid-1970s, this day-use problem did not exist in the other Alaskan parks and monuments, because existing regulations effectively prevented the proliferation of outside commercial operations.

In December 1978, however, the problem of how to manage day-use visitors became an issue throughout Alaska. When President Jimmy Carter created 56 million acres of new Alaskan national monuments, the staff at the Alaska Area Office realized that they needed some mechanism by which they could verify and sanction commercial activities taking place on those lands. In early 1979 officials approved and mailed letters of authorization to known commercial operators; these form letters approved a broad range of activities in specified park areas created by the 1978 proclamation. [7]

This admittedly ad hoc solution provided little information about either the operators or the activities carried on in the monuments. Officials recognized that the intensity of activities covered by many of the letters of authorization was sufficient to justify the creation of concession contracts. The time delay in creating concession contracts, however, made it impractical to consider that course of action as a stopgap measure; besides, Alaska's political climate at the time was such that the Service was in no position to impose high fees and myriad operating restrictions on Alaska's guiding community.

Officials at the agency's Washington office, therefore, set out to create a system which would provide a modicum of regulatory authority over outside commercial activities in Alaskan parks, but without the expenses and restrictions inherent in concession contracts or concession permits. On April 4, 1980, the Acting Associate Solicitor for Conservation and Wildlife paved the way for a separate licensing system when he concluded that "there are activities which need not be considered as concessions operations within the meaning of the [1965] Concessions Policy Act." But he warned that he could not authorize a license for Alaska that was not also available throughout the system. [8] He soon launched an effort to create a nationally applicable license. To assist the Alaska monuments, however, he issued a draft Commercial License on May 2. He recognized that the license, which was approved in its final form later that month, was intended to be applicable only during the summer of 1980. [9] Meanwhile, efforts toward creating a more broadly applicable license continued for the remainder of the year.

The Commercial Use License (CUL) was finally approved in early 1981. Based on language contained in 36 CFR § 5.3, it was less restrictive than either of the other concession documents. The CUL, like the Commercial License which preceded it, required that as long as guides or other operators did not erect structures within the parks, they were free to do business by meeting a few, minimum standards of performance. Among these requirements were the possession of liability insurance, worker's compensation insurance, and an Alaska business license. The licenses were available for a nominal processing fee, and were available to any qualified party. [10]

The commercial licenses issued at Katmai in 1980, and refined the following year, represented a marked departure from "business as usual" in the Alaska concessions field. At Alaska's two other large, older NPS units, Mt. McKinley and Glacier Bay, superintendents had chosen to limit all but a few commercial licenses to the newly-expanded areas of those parks. At Katmai, however, usage levels were so low that, in the superintendent's opinion, the entire enlarged park could sustain commercial activity. Therefore, the commercial licenses issued at Katmai in 1980 (and in subsequent years) gave outside interests the authorization to operate anywhere in the park and preserve. The way was thus paved for the relatively laissez faire commercial development which has characterized the park in the last ten years. [11]

Although a primary reason behind the establishment of the commercial license system was the regulation of activities in America's parklands, the system has also provided park managers with a broad statistical database on the amount of visitation taking place throughout the parks. Each time individuals apply for the CUL, they are asked to indicate the park units they intend to use during the period encompassed by the license; they are also asked to delineate the nature of the activities that will be sponsored at those parks. In addition to the information on the license itself, users of Alaska parklands are asked to describe the nature of that use—the number of visitors, the length of stay, the type and location of use—on a so-called activity summary.

Many CUL holders, in order to cover all trip possibilities, have asked for authority to use parks they never visit. Other park users, particularly those who were active in the early to mid-1980s, failed to fill out activity summaries. (Existing licensees have had to complete activity summaries before license renewal; beginning in 1989, Katmai CUL holders have been encouraged but not required to complete a special statistical sheet that has largely replaced the activity summary.) Because no statistical measure accurately tracked CUL activity before 1989, the amount of commercial activity to take place in Alaska's parks cannot be known with precision; one can only be sure that the number of operators to visit a given park is at least as great as that provided in the activity summaries. The actual number of operators is probably fairly close to the number of recorded activity summaries, particularly in recent years; therefore, most of the statistical generalizations made in the following section are based on data provided in the activity summaries.

Growth of Commercial Use License

Activity

The Commercial Use License and the documents which preceded it have provided a framework under which commercial recreational activities have taken place within Alaskan national park units. This system, however, started somewhat late at Katmai. Only two commercial enterprises, Arcticsport: Expeditions North and the Enchanted Lake Lodge, were provided letters of authorization in 1979 for the "new additions to Katmai National Monument." [12]

The following year fifteen businesses, one of which was Arcticsport, obtained commercial licenses for the monument. Park officials hoped that the system would be in place before the season began. Because the forms were not finalized until late spring, however, the first such licenses were not signed until early June. [13] Permits continued to be signed throughout the summer season; the last valid Katmai license was not signed until early August. [14]

Of those fifteen businesses, only four were known to sponsor trips into the park. Three of the four were fishing lodges based in the vicinity of the monument: Wood's Alaska Sport Fishing, operated by Jack Wood, and Wood-Z-Lodge, operated by Ron Archer and Charles Wood, and Mt. Peulik Lodge/Beluga Wilderness Outfitters, operated by Gerald Yeiter. The fourth, Sobek Expeditions, was a California-based outfitter who sponsored hiking, backpacking and kayaking expeditions; it served Denali National Monument as well as Katmai. The most popular 1980 visitor destinations for the guests of commercial use licensees were Naknek Lake and Naknek River, both of which could be reached by road from King Salmon. A sprinkling of visitors joined fly-in trips to Nonvianuk River and American Creek. [15]

The four companies which filed activity summaries should not be taken as an accurate count of the number of active Katmai guiding companies active at Katmai. But as noted above, ten or more such companies may have been operating. The gap existed because the NPS was slow to implement the CUL system. Public attitudes in Alaska urged a slow, steady approach, and it took several years before the guiding community became aware that a CUL was needed. Concessions officials have suggested that it was not until the late 1980s that the number of companies providing activity summaries was a relatively accurate reflection of the number of trips taken by guiding companies in the various Alaska parks. [16]

Although relatively few guides took people into the park in 1980, the next few years saw an explosive growth in that activity. The number of companies known to be using the park, for instance, grew from four in 1980 to 21 in 1981 (Table 1). By 1982, that number had increased to 30. At least 33 companies entered the field between 1980 and 1982, but five companies discontinued operations on either a temporary or permanent basis. Surprisingly, 15 of the original 33 Katmai guiding companies are still in business. [17] Some, perhaps most, of that growth was the result of new companies entering the field; the remainder of that growth was because an unknown number of existing users signed up as CUL holders.

| Table 1. Summary of Commercial Use License Activity at Katmai National Park and Preserve, 1980-1990 | ||||||||||||

| Number of CULs Issued | Number of Activity Summaries Received | Sport Fishing: | ||||||||||

| Year | Total | Present CULs | Former CULs |

Grand Total | Pres. CULs |

Fmr. CULs | New CULs |

Pres. CULs | Fmr. CULs | Disc. CULs |

# of CULs | Activ. Summ |

| 1980 | 17 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 3 |

| 1981 | 33 | 7 | 26 | 21 | 6 | 15 | 17 | 5 | 12 | 3 | 20 | 18 |

| 1982 | 50 | 18 | 32 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 32 | 25 |

| 1983 | 63 | 24 | 39 | 36 | 20 | 16 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 38 | 27 |

| 1984 | 61 | 28 | 33 | 34 | 21 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 39 | 28 |

| 1985 | 76 | 34 | 42 | 42 | 29 | 13 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 51 | 32 |

| 1986 | 75 | 38 | 37 | 47 | 34 | 13 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 54 | 36 |

| 1987 | 85 | 46 | 39 | 52 | 39 | 13 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 59 | 39 |

| 1988 | 83 | 53 | 30 | 58 | 52 | 6 | 15 | 13 | 2 | 5 | 59 | 43 |

| 1989 | 74 | 67 | 7 | 58 | 57 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 54 | 42 |

| 1990 | 72 | 71 | 1 | 59 | 59 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 50 | 40 |

|

Source: Commercial Use License files, ARO-OC. NOTE: "Pres. CULs" are those which were operating in 1991; "Frmr. CULs" are formerly active companies which had ceased operations prior to 1991. | ||||||||||||

Sport fishing remained by far the most popular activity during the early 1980s. At least 75% of the companies reporting CUL activity at Katmai from 1980 to 1982 provided sport fishing excursions. The majority of the 1982 Katmai license holders, in fact, visited the park exclusively to fish. No more than three lodges organized expeditions offering any other kind of recreational pursuit.

As the number of outside users of the park grew, the geographical diversity of their destinations expanded as well (Table 2). In 1980, the only places that outside guides were known to take visitors were Naknek Lake, Naknek River, the Nonvianuk River, and American Creek. But in 1981 the first known CUL trips to Brooks and Kulik camps took place; [18] pioneering trips were also taken to the Contact Creek and to the outlets of Gertrude Lake, Lake Grosvenor, and Nonvianuk Lake. In 1982 CUL holders first began taking clients to Idavain, Moraine and Margot creeks, to the Big and Kamishak rivers, and to Murray, Hammersly, Battle and Kukaklek lakes.

| Table 2. Sport Fishing and Float Trip Activity in Katmai National Park and Preserve, 1980-1990 | |||||||||||

|

NOTE: Top figure for each geographical location and year is the number of active operators in that area; bottom figure is the number of clients appearing in the activity summaries. | |||||||||||

| Location | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 |

| A. Rivers | |||||||||||

| Alagnak River: (unspecified) | 1 5 | 3 88 |

3 124 | 2 45 | 1 208 |

3 520 | 6 674 | 6 668 |

10 325 | 16 583 | 32 3769 |

| Kukaklek River | 1 5 | 1 2 | 2 16 |

1 6 | 2 19 | ||||||

| Nonvianuk River | 1 50 | 2 17 |

2 22 | 3 62 | 2 79 |

6 45 | 5 40 | 3 22 |

2 30 | ||

| American Creek | 1 3 | 1 15 |

3 21 | 3 630 | 3 1341 |

5 874 | 4 71 | 5 153 |

8 733 | 10 922 | 7 603 |

| Big River | 1 n/a | 2 66 | 4 153 | 4 175 |

6 158 | 9 359 | 7 345 |

11 511 | |||

| Brooks River/Camp | 3 60 | 6 243 |

8 631 | 9 854 | 7 581 |

10 274 | 11 146 | 19 1101 |

18 1871 | 34 7453 | |

| Idavain Creek | 1 n/a | 2 79 | 1 60 | 2 43 |

5 252 | 3 147 | 2 93 | ||||

| Kamishak River | 1 n/a | 1 468 | 4 117 | 6 619 |

7 438 | 8 527 | 10 566 |

8 974 | |||

| Kulik River | 1 5 | 3 42 |

2 3 | 2 48 | 3 53 |

3 46 | 5 93 | 8 632 |

11 900 | 10 1115 | |

| Moraine/Funnel Creek | 1 n/a |

1 36 | 2 53 |

3 84 | 3 69 | 7 283 |

17 355 | 16 1715 | |||

| Other Rivers: | 7 314 |

7 333 | 13 361 | ||||||||

| Alagogshak Creek/ Margot Creek | (M) 1 n/a |

(M) 1 10 | (A) 1 12 |

||||||||

| Contact/Angle Creek | 2 81 |

2 74 | 1 12 | 1 20 |

1 315 | 1 360 | 1 360 |

||||

| Hardscrabble Creek/ Savonoski River | (H) 1 12 | (S) 1 24 |

|||||||||

| B. Lakes/Ocean | |||||||||||

| Park Lakes: | 3 23 | 3 18 | 7 114 | ||||||||

| Battle Lake | 2 6 |

1 9 | 2 29 | 1 4 |

1 8 | ||||||

| Bay of Islands | 1 3 | 4 15 |

1 11 | 2 28 | 1 6 | 3 21 | |||||

| Grosvenor Lake | 1 6 | 2 6 |

1 5 |

||||||||

| Hammersly Lake/ Murray Lake | (H/M) 1 n/a |

(H) 2 41 | |||||||||

| Naknek Lake/Naknek River/Lake Camp | 2 160 |

7 1020 | 9 760 | 7 1153 |

9 1219 | 8 1086 | 8 1483 |

9 1472 | 5 642 | 5 694 |

5 671 |

| Preserve Lakes: | 1 20 | 8 286 |

6 307 | 9 446 | |||||||

| Kukaklek Lake | 3 80 |

1 n/a | 3 51 | 1 38 |

3 34 | 5 90 | 2 127 | ||||

| Nonvianuk Lake | 2 9 | 2 15 |

4 107 | 3 124 | 2 100 |

2 17 | 3 19 | ||||

| Coastal/Cook Inlet Areas: | 2 180 | 2 360 | 2 310 |

4 552 | 5 469 | 5 219 |

6 406 | 8 638 | |||

| TOTAL, ALL AREAS: | 4 168 | 21 1337 |

30 1403 | 36 2803 | 34 4396 |

42 4373 | 47 4573 | 52 4269 |

58 5861 | 58 7514 | 59 22745 |

|

Source: Commercial Use License files, ARO-OC. | |||||||||||

Despite the diversity of areas visited, most fishermen chose to carry on their fishing in just a few areas. In 1982, for instance, more than half (54 percent) of the 1403 fishermen that reportedly visited Katmai did so on Naknek Lake or Naknek River. Another 17 percent of those visited Brooks Camp, and ten percent fished along some portion of the Alagnak River. Only 20 percent of Katmai's visitors, therefore, ventured into the remainder of the park.

As noted above, most of the 1980 Katmai visitors who had been guided to their destinations arranged their trips through one of two King Salmon-based companies. But as the demand for Katmai trips increased, visitors sought out a wide variety of guiding outfits, which were based in locations scattered across southwest Alaska and beyond. Of the 30 guiding companies known to be active in Katmai in 1982, almost half were based in King Salmon. But another third were scattered around the Lake Clark-Bristol Bay region. Only four holders of Katmai Commercial Use Licenses were based outside the region.

Between the early and mid-1980s the Katmai guiding industry continued to grow, though not as quickly as it had earlier in the decade. The number of active guiding companies increased from 30 in 1982 to 36 in 1983; then, after a slight drop to 34 in 1984, eight more companies were added in 1985. What accounted for the rise was that at least 25 new guiding companies (14 of which are still active) entered the Katmai market between 1983 and 1985. Fourteen other companies discontinued operations during the same three-year period.

Sport fishing continued to rank far and away the most popular reason to take a guided trip to Katmai, but a respectable number of lodges also began to offer float trips and photography/sightseeing expeditions. The number of air taxi companies was another sector of recreational use that witnessed significant gains between 1982 and 1985. As noted above, part of the activity increase during this period is doubtless related to the increasingly effective efforts which NPS officials made in convincing commercial operators to obtain Commercial Use Licenses. But there was also a substantial increase in the level of recreational activity.

During the mid-1980s guiding companies began to offer trips to several new areas; some of these areas grew to become some of the park's most popular fishing areas. Expeditions along the Pacific coast, for example, began in 1983. The first visitors were not registered along the Kukaklek River portion of the Alagnak River until 1985. No trips were recorded along Alagogshak Creek, at the southern tip of the park, until 1986.

By the mid-1980s, therefore, the organizers of Katmai fishing expeditions had had the opportunity to fully explore the park's rivers and lakes and the fishing possibilities within them. Overcrowding of the most popular areas, combined with an increasing knowledge of the park's more distant hinterlands, caused the fishing pressure to become more decentralized. Figures in the activity summaries show that between 1982 and 1985, the total number of outside visitors tripled, from approximately 1400 to more than 4300. The most popular area in the park continued to be Naknek Lake and Naknek River. Despite a 43 percent rise in the number of fishermen (to 1086), the Naknek drainage received only 25 percent of total visitation, a 29 percent drop from three years earlier. Likewise, the number of outside fishermen visiting Brooks Camp rose 139 percent between 1982 and 1985, but the area's share of total visitation dropped from 17 to 13 percent. Visitation levels to the Alagnak River were sufficiently healthy that its share of total visitation rose slightly, from ten to 12 percent; therefore, the three areas which, in 1982, accounted for some four-fifths of outside fishing visits, accommodated only half of those visits three years later.

Areas of interest that rose to prominence between 1982 and 1985 included American Creek, Contact Creek and the coastal areas. American Creek, which few visited prior to 1983, exploded in popularity in 1983 and 1984. (The ramifications of that growth are discussed in more detail in the next section.) Although the number of fishermen visiting in 1985 (874) was a significant decrease from the previous year (1341), it was still high enough to be the second most popular fishing area in the park, attracting 20 percent of the total number of fishermen who came with outside guides. Both Contact Creek and the coastal areas also grew from insignificant positions in 1982 until, three years later, both were attracting over 300 visitors, or seven percent of CUL traffic.

Between the early and mid-1980s, organizations from increasingly remote places began taking visitors to Katmai. While in 1982 fully half of the guiding outfits were based in King Salmon, that share had fallen to one-third by 1985. The number of guiding companies based in the Bristol Bay and Lake Clark areas increased slightly; more remarkable was the increase in the number of companies based in Anchorage. In the mid-1980s a company based in Homer also signed on as a CUL; this was one of several outfits which serviced the expanding interest in fishing the park's Pacific coastline.

Since the mid-1980s, the Katmai guiding industry has grown in fits and starts. Between 1984 and 1987, for example, the number of active guiding companies climbed from 34 to 52, but the number of visitors brought to Katmai dropped from approximately 4900 to 4300. From 1987 to 1990, however, the number of guiding companies grew only modestly while the number of visitors more than tripled. The reason visitor totals levelled off in the mid-1980s is at least partially attributable to poor economic conditions in the state following the oil boom of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The subsequent increase in visitor levels is in part due to improving economic conditions in the state. The major reason why recorded visitor totals grew so dramatically is because NPS concession personnel began requiring completed activity summaries before new Commercial Use Licenses could be granted.

Sport fishing is still the prime reason guides take visitors to Katmai; in 1990, 40 of the 58 active guiding companies sponsored sport fishing expeditions. Remarkably, however, 20 companies (more than four times as many as in 1985) also took sightseers or photographers into the park. The number of air taxi operators roughly doubled to 15 between 1985 and 1990. Fourteen CUL holders sponsored float trips, while seven holders of CULs sponsored backpacking trips. Mountaineering, kayaking, hunting, and winter activities aroused a relatively minor amount of interest in 1990 as, indeed, they did throughout the 1980s.

Between 1985 and 1990 the number of visitors flocking to Katmai's fishing areas continued to escalate. In 1990, activity summaries estimated that more than 11,600 fishermen utilized guiding companies to visit the park. Brooks Camp, a world-famous fishing mecca, attracted 7400 visitors, the most popular destination within the park. (Many of those visitors did not fish, choosing to sightsee instead.) Other locations in the park, which attracted fishermen almost exclusively, were experiencing crowding problems of their own. Kulik River, the Naknek lake and river system, American Creek, and the Alagnak River system all attracted more than 500 guiding-company clients in 1989. Five other areas received at least 200 of these visitors; they included Kamishak River, Moraine and Funnel creeks, other Pacific coastal areas, the preserve lakes, and Big River. With the notable exception of the Kulik River, the five most popular areas were the same as those of 1985. [19] Most of the areas which received between 200 and 500 guided visitors in 1989 had been relatively unknown four years before.

The late 1980s witnessed a further decentralization in the location of the home bases of Katmai's licensees. In 1982, about half of Katmai's CUL holders had been located in King Salmon, and three years later about a third were. By 1989, however, only about a quarter were located there. The further decrease took place because the number of King Salmon-based CUL holders remained essentially stationary during the same time-period that the total number of licensees increased about 40 percent. In part because the Togiak National Wildlife Refuge began to limit the number of guides, the number of lodges and outfitters based in the Bristol Bay and Lake Clark areas grew from 12 to 17. Their proportion of all CUL holders in 1989 remained much the same as in 1985. The biggest growth took place outside the immediate region. On Kodiak Island and the Kenai Peninsula, the number of outfitters holding Katmai CULs rose from one to four during the four-year period, while the number of Anchorage-area outfitters with Katmai licenses increased from nine to 13 over the same period. As a result, the largest number of Commercial Use License holders are now held by companies which are located in southwest Alaska but outside of King Salmon. Outfitters located in southwest Alaska, including King Salmon, now constitute about three-fifths of all Katmai licensees, while another quarter are home-based in Anchorage. Less than ten percent of active licensees are located outside of southwestern or southcentral Alaska.

The American Creek Permit

System

As Katmai's lakes and rivers increased in popularity in the early and mid-1980s, both NPS officials and commercial users began to become concerned that certain areas were becoming congested. Many individuals, of course, reacted to the growing crowds by moving on to more remote fishing locations; many guides as well as fishermen, however, have continued to return to areas offering consistent, quality fish runs. Katmai is extremely fortunate in having a good selection of excellent trout and salmon streams. In most areas of the park, the sheer breadth of the lakes and length of the rivers has been sufficient to spread the effects of the growing population of fishermen. Other waterways, however, are physically and ecologically unable to support a large fishing population.

American Creek, located in the northwestern section of the park, is one of Katmai's most famous, productive rainbow trout fisheries. It also offers excellent runs of salmon and char. [20] The stream, whose headwaters lie in Murray and Hammersly lakes, passes through a rocky gorge for some of its length, thus preventing fishermen from accessing all but the last eight miles before it debouches into Lake Coville. American Creek is a relatively shallow, meandering stream in its lower reaches; fly-in fishermen, therefore, can land either at the mouth of the river (after which they ascend the river by motorboat), or on the river a mile or two upstream from the mouth. On a quiet day American Creek can be an exceptional experience, but given too many fishermen, problems of congestion and noise may well erupt. [21]

Prior to 1979, relatively few people knew about American Creek. Northern Consolidated Airlines began flying Grosvenor Camp guests to the creek in the late 1950s; by the mid-1960s, it was flying Kulik Lodge guests there as well. Edwin Seiler, owner and operator of Enchanted Lake Lodge, began flying guests to the creek in 1964. [22] Beginning about 1971, Wien placed a boat at the river's mouth to transport guests upstream. By the early 1980s three other lodges, Mt. Peulik Lodge, King-Ko Inn, and Iliaska Lodge, were also flying guests to American Creek, and one of them left a second boat at the site. [23]

Available figures, generated from activity summaries, suggest that fewer than fifty anglers used the creek each year through the 1982 season. In 1983, however, the creek was "discovered." It attracted more than 600 fishermen that season; in so doing, it became as popular with anglers as the Brooks River area. News of the creek spread that winter, the result being that more than twice as many anglers descended on the creek in 1984 as in 1983. With more than 1300 visitors, most if not all of them fishermen, the creek became the most popular fishing hole in the park.

The sudden surge in popularity impinged on the quality of the experience for both fishermen and guides. The number of boats stationed at the creek mouth, which by 1984 had grown to eight, created congestion in the area. Safety hazards were created as a result of the inevitable encounters between aircraft that were under way, and between jet boats traveling around blind corners at the high speeds necessary to negotiate the shallow river. Seventeen areas along the river, boat storage areas in particular, lost soil and vegetation from recreational impacts. Although virtually all of the river's visitors subscribed to a rigorous catch-and-release philosophy—the only fish caught and eaten were a few arctic char—some guides felt that the high usage levels had decreased the size of rainbow trout. [24]

Because of these impacts, most users acknowledged that the existing system had to be changed to guarantee a high quality fishing experience along the creek. Local NPS officials conducted a series of patrols along the creek during the summer of 1984, and felt that the best way to deal with the worsening situation was to host a series of meetings, to be attended by all interested parties, including the owners of lodges and the sport fishing guides who used the creek. Three such meetings were held: in August 1984, May 1985, and August 1985. [25]

Perhaps at the suggestion of Ted Gerken, who was one of the lodge owners, Chief Ranger Loren Casebeer and Superintendent David Morris moved toward the implementation of a permit system, which would limit the number of lodges allowed to leave a boat along the river. Recognizing the limitations of the CUL system in this situation, the park staff argued that the instigation of concession permits was the only way to legally allow the storage of boats inside the park. The permit system was also effective in dealing with problems of overuse. [26]

To gain more information on user patterns along the creek, the NPS stationed a seasonal technician in the area during the summer of 1985. [27] The employee lived in the former National Marine Fisheries Service quarters at the east end of Lake Coville, and commuted to the site by jet boat. [28]

By the time the prospectus calling for permit applications was issued in January 1986, it was announced that only six such permits would be awarded. [29] Eighteen lodges were requested to submit permit applications; another 35 persons, either CUL holders or other interested parties, were sent public notices describing the prospectus and permit. [30] The application deadline was set for March 7, a date which was later extended to March 21.

The new two-year concession permits being offered represented a higher level of regulation than the commercial use licenses then in effect. Whereas the current fee for CUL holders was $50 per year, which included the right to access within any of Alaska national park units, each holder of a concession permit would be required to pay $500 per year, plus an additional $2.00 each time a visitor was taken out to American Creek. The permit would allow the holder to keep a boat overnight along the creek; that boat, however, could not exceed 17 feet in length, nor could its motor exceed 50 horsepower. The boat had to be registered with the Coast Guard and had to meet their standards of safety and operational performance. Each permit holder would be further required to limit its use of the creek, to four clients and one guide per day. [31]

Despite the costs and restrictions promised by the new system, thirteen operators responded to the prospectus. To evaluate the applications, a four-person panel was formed at the Regional Office. That panel met on March 27. They determined that the six most highly rated lodges were: [32]

| Name of Permittee | Location | Owner |

| Adventure Unlimited | King Salmon | Mike Branham |

| Branch River Air Service | King Salmon | Van Hartley |

| Bristol Bay Sportfishing | Iliamna | Bruce Johnson |

| Mike Cusack's King Salmon Lodge | King Salmon | Mike Cusack |

| No See Um Lodge | King Salmon | Jack Holman |

| Rainbow King Lodge | Iliamna | Ray Loesche |

Letters were sent to winning and losing applicants in April 1986. Those who were selected quietly signed their permits during June and July. [33] Not surprisingly, however, a howl arose from those who were not selected. NPS officials, both at the park and regional levels, were challenged to defend the necessity of adopting a permit system as well as the process of criteria selection. One applicant felt that the selection process had been rigged, another that financial criteria should not have been a basis for permit selection, and several charged that a newcomer (such as Bruce Johnson, owner of Bristol Bay Sportfishing) should not have been chosen over those with established use patterns. Challenges were made by the applicants themselves and their attorneys; the applicants also sought assistance from the Congressional delegation. [34]

One of the challenges was successful. Raymond F. Petersen, who represented Katmailand, Inc., was denied a permit in late April, and was ordered to remove his boat from the creek by June 10. But Petersen, feeling that "there was some flaw in the selection process," appealed the panel's decision. His appeal was initially denied. [35] Petersen, however, argued that the terms of his company's concession contract gave it preferential rights within the pre-1978 boundaries of the park; among those rights was its ability to keep a boat at the mouth of American Creek which, after all, was within those boundaries. By early June the National Park Service had recognized its mistake, and reversed its earlier decision. It allowed Katmailand to store its boat on the river without benefit of a permit; the boat, moreover, did not need to follow the guidelines required by the permittees. [36] Since that time, seven companies have been allowed to keep boats along American Creek. Katmailand has been allowed to keep one boat within the so-called "old park," while the other six permittees have been required to beach their boats in the "new park." [37]

As noted earlier, both the NPS and most of the guiding businesses agreed in concept to the two-year concession permits. The Sierra Club, however, protested the decision because it felt that a study of the creek's resources needed to be made before permittees would be allowed to leave boats on the banks. The park overruled that protest. [38]

The agency was as concerned as the Sierra Club about the creekside ecology. Therefore, in order to ensure compliance with the conditions of the American Creek permits, and to observe the effect that the permittees and contractor had on American Creek resources, the park stationed field personnel in the area for the second straight year. The agency also agreed to fund the first year of a proposed four-year research effort, the purpose of which was to determine if boating activities relating to concessions adversely affected the area. Funding for the study was shared between the park and the regional concessions office. [39] To provide housing for the field staff, the old National Marine Fisheries Service buildings were abandoned in favor of a Weatherport tent, located a mile up the creek from Lake Coville. Field duties were assigned to rangers Ron Antaya and Colleen Matt. [40]

The rangers were obligated to spend much of their time performing collateral duties away from American Creek. Therefore, they were unable to ascertain an exact number of fishermen who visited the creek. They did find that each of the permittees was "very cooperative and complied well with permit stipulations and park regulations." Two of the six permittees did not bring guests to the river, but several lodges which did not hold permits visited the area from time to time. Katmailand, for instance, maintained two boats (one from Grosvenor Lodge, another from Kulik Lodge), and the Alaska Rainbow Lodge flew a 13-foot Zodiac to the river each time it brought clients. [41]

The creation of the permit system had a significant impact on usage levels along American Creek. Total visitation dropped sharply between 1984 and 1986. Although statistics on visitor usage along American Creek (as elsewhere outside of Brooks Camp) are suspect before 1988, it appears that the annual number of fishermen visiting the creek in recent years is only about half that which took place during the peak summer of 1984. [42]

During 1987 Katmai staff, including a biological technician and a park ranger, continued to monitor the activities of the permittees. They noted that while two of the six permittees, for the second consecutive season, did not use their permits, three permittees allowed other lodges to use their permits under specific terms and conditions dictated by the NPS. The result of this process was that a total of twelve lodges—ten via the permit system, plus the two Katmailand lodges—used American Creek in 1987. In this way, many of the lodges which had been denied a permit in the spring of 1986 obtained legal access to the creek.

A total of 922 fishermen used the creek that summer. Of that number, 648 (70.5%) came from lodges that held or used concession permits, while 270 (28.5%) came from the two Katmailand lodges. Grosvenor Lodge, which accounted for 217 guests, was the largest single generator of American Creek fishermen. Despite the large number of users, however, lodges spaced their activities to such an extent that problems with overcrowding did not take place. Rangers found that there were only two days all summer that five or more boats were on the river, and there were only six days where more than three boats were active. The only problems reported were relatively minor violations related to Coast Guard regulations for boat equipment, bear-proof food containers, accuracy in keeping up guide books, and similar matters. [43]

Because the concession permits granted in the spring of 1986 were valid for a two-year period, NPS officials met during the winter of 1987-88 to consider a new series of applications. The terms of the permit were similar to those offered in 1986; the only substantial change was that the fee was changed to a flat $600 per year. By the time the application period closed on March 24, the Alaska Regional Office had received responses from ten businesses: the six original permittees and four new applicants. [44] On March 31, and again on May 26, a three-person rating panel met to evaluate each application. After some deliberation, the panel chose to recommend renewal of the concession permits to each of the six incumbents. [45]

In the summer of 1988, therefore, American Creek's permit holders were the same as had existed during the previous two years. To monitor their compliance with the provisions of their concession permits, and to determine if boating activities adversely affected the area, the park continued to staff personnel along the creek in both 1988 and 1989. The ranger and biological technician assigned to the creek in 1989, however, were unable to devote their full-time efforts to goings-on at American Creek, and they were similarly unable to finalize an end-of-season report. [46] The lack of a full season's work meant that the four-year Concession-sponsored research study aimed at determining the effects of boating activities on the area came to a sputtering, inconclusive halt; as a result, park resource personnel were unable to provide scientific estimates for recreational carrying capacities along the creek. [47]

By 1990, it had been hoped that a study evaluating the resources along the creek would have allowed permits to be effective for a four-year period. But because the study was never completed, prospectuses were issued for another two-year permit in late February and early March. The panel evaluating those applications met on May 15, then again on June 21. It decided that five of the six current permit holders should be awarded a new permit. The sixth permittee, Rainbow King Lodge, was replaced by the most highly-rated new applicant, Larry Suiter of Freebird Charters, Inc. The new permittee, based in King Salmon, was told of his success in a letter dated May 24, 1990. Letters were written to the remaining permittees a month later. [48]

At the present time, therefore, American Creek still has six permit holders, five of which have been active since the permit system went into effect in early 1986. [49] It also supports fishermen from one of the Katmailand lodges and others who may bring day boats into the area from time to time. The imposition of the permit system has, as expected, prevented further growth in visitation, this during a time when most of the other drainages in the park have witnessed substantial increases in fishing pressure. Limited data gathered in recent years suggests that the creation of the permit system has slowed if not halted the spread of ecological degradation which had been taking place in the early 1980s. Whether the ecosystem can absorb higher use levels before degradation takes place is a question that remains unanswered. [50]

Watersheds Considered For Concession

Permits

As noted above, most observers recognized back in 1984 that the noise, crowding, and environmental degradation witnessed along American Creek demanded that an enhanced system of regulation be implemented. Similar conditions have also been witnessed in several other Katmai watersheds. These watersheds include Brooks River, Big River, and Kulik River. As of yet, however, no other areas have been seriously considered for inclusion in a permit-type system.

Most of the suggestions for enhanced regulation in other watersheds took place during 1984 and 1985, when the American Creek system was being proposed. Problems first surfaced during the summer of 1984. In his annual report the Katmai superintendent, David Morris, showed a primary concern for matters at American Creek. In addition, however, he noted that

Visitor conflicts became evident at Big River and Kashvik Bay [sic] where as many as seven planes and twenty-eight fishermen vied each day for favorable positions during the silver salmon run. Their behavior toward each other fell well short of exemplary. [51]

During a series of meetings between guides and the agency in the late summer of 1984, many of the same concerns were recognized. Participants recognized that a few of the park's rivers were major pressure points. On a more general level, guides expressed concerns that if American Creek became restricted, the resulting increase in use at other rivers would eventually cause every creek to be restricted. [52]

These concerns were recognized by local park officials. During the following winter, Superintendent Morris hinted that several park areas demanded an increased degree of regulation. He declared that Brooks River, Big River, Kulik River, and American Creek had "all experienced sharply increased use, which may be changing the character of the visitor experience. There may be other emerging pressure points of which we are unaware." [53]

Park staff further complicated matters when they began enforcing regulations against boat storage on Katmai's rivers in 1985. During a spring meeting, they warned guides that the number of boats on any creek would henceforth be restricted, because the agency had no authority to allow the storage of boats under the commercial use license system. [54] The message was implicit but clear: if guides insisted on leaving boats within park watersheds, park officials would have no choice but to implement a concession permit system.

The park, of course, went on to implement such a system along American Creek. Elsewhere in the park, however, guides were in no mood to accept these regulations. Since that time neither the commercial users nor park officials have felt that other watersheds demanded a permit system, and American Creek has remained the only area given serious consideration for such regulations. This is despite the fact that each of the watersheds which were noted as trouble spots in 1984 has grown sharply in popularity in recent years. [55]

At Brooks Camp, the conflict over fishing was just one of a host of problems witnessed along the river. In 1985, guides recognized that Brooks received more fishing than American Creek, but the Service was unwilling to limit the rights of commercial users unless there was a consensus among those users to do so. [56] Superintendent Morris recognized that part of the problem was the role of Brooks Camp as a "meat fishery" for lodges throughout southwest Alaska—a place where lodge guests could be assured of catching and keeping four or five fish. He therefore instituted a rule limiting the catch along the river to two fish per person per day. Ray Bane, his successor in 1987, further reduced that limit to one. The new rulings preserved the fish stocks, slowed the traffic of "meat fishermen" to Brooks Camp, and reduced the number of bear-human incidents along the river. [57]

Big River, a coastal stream at the eastern end of the park, has been a problem area, even though it is not one of the park's most popular fisheries. Activity-summary statistics show that the first commercial guides did not visit the area until 1984. By the end of the decade, the river still ranked tenth in popularity among the Katmai watersheds. But by the mid-1980s, user patterns brought serious conflicts. What draws fishermen to the river is a short but plentiful silver salmon run which usually takes place in August. Calls for regulation of the salmon run, first heard in the summer of 1984, were in part based on overcrowding—"a three ring circus," in the words of a former superintendent—because takeoffs and landings can take place on only a short stretch of the river. Also, confrontations between fishermen and bears ensued because users did not properly clean and store their fish. [58]

To monitor the visitor influx to this and other coastal rivers, Katmai rangers established a coastal ranger patrol in 1984, and conducted patrols along several bays and rivers during the summers of 1984, 1985, and 1986. In 1985, staff observed "as many as six lodges and/or thirty fishermen per day" during the Big River salmon run. Noting that there was "a history of inappropriate behavior toward bears, and tensions between commercial operators have intensified in recent years," the staff was asked "to 'counsel' guides or fishermen who either don't understand policy or choose to ignore it." [59] During 1986 rangers carried on a similar task, and by the end of the summer were pleased to note that "as a result of the continuing effort, confrontations between bears and fishermen resulting from improper storage of fish were significantly reduced." Similar improvements were noted at Kamishak River and Hallo Creek. [60] Problems at Big River continue to the present day, but the methods encouraged by the ranger patrols, and their continued presence during the height of the salmon run, appear to have reduced the need for a permit-based regulation system. [61]

At Kulik River, located just north of Kulik Lodge (one of the Katmailand facilities), early users were almost entirely lodge guests. The river, and the lake east of the lodge, were visited by scattered guides during 1981 through 1983. In 1984, however, use skyrocketed. According to one guide, it all began "when one [outside] lodge started to use the river, [therefore] other lodges decided it was no longer exclusive for Kulik Lodge and that they could go there too." [62] Katmailand officials reacted angrily to the invasion of territory they regarded as theirs, and soon NPS officials were receiving reports that fly-in fishermen were being harassed by jet boats and low-flying planes. Calls for a permit-style system, which may have been encouraged by the staff at Kulik Lodge, continued into 1985. [63]

Kulik River remains one of Katmai's most popular fisheries; in 1989, for instance, the spot attracted more fishermen than any place else except Brooks Camp. Kulik Lodge guests numbered a plurality, though not a majority, of the total number of fishermen along the river that year. [64] Because crowds there continue to increase, overcrowding is a growing problem. Most of the fishermen have been respectful to the surrounding resources, but in the fall of 1988 several parties were observed harassing bears which had come down to the river to feed. [65]

Katmai Hunting Permits

As noted at the beginning of the chapter, little hunting has traditionally taken place within the boundaries of Katmai National Park and Preserve. The "old monument," and present-day Katmai National Park, are off-limits to hunting; the activity is allowed only in Katmai National Preserve, a relatively small area north and west of Nonvianuk Lake. Through the mid-1980s, hunters in the preserve were primarily regulated by the state. More recently, the degree of regulation increased when the NPS organized its own system of hunting permits.

Before 1978, hunting was prohibited within the boundaries of Katmai National Monument. As noted in Chapter 1, the fear of depleting the existing game population was a major factor responsible for expanding the monument in 1931. Almost twenty years later, a major reason behind establishing a seasonal presence within the park was related to the enforcement of the existing hunting and trapping regulations.

On December 1, 1978, President Jimmy Carter expanded Katmai National Monument by 1,370,000 acres. The land included in that expansion was closed to hunting. [66] The proclamation creating the expanded monument was intended to be in force only until Congress passed a more comprehensive legislative Alaska lands package. Such an event took place two years later when the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act was signed into law. As noted in Chapter 4, ANILCA expanded Katmai into a national park and preserve; the total size of the NPS unit, however, changed little from its interim (1978) acreage. Compared to the acreage that had existed prior to 1978, the passage of ANILCA added 1,037,000 acres to the national park; a provision in the act decreed that Katmai National Park, unlike other Alaska national parks, would be closed to subsistence as well as sport hunting. In addition, ANILCA create a 374,000-acre national preserve in which both sport and subsistence hunting was allowed. The preserve was a single, irregular block located at the north end of the newly-established NPS unit. [67]

When the monument was expanded in 1978, several hunting guides lost territory that had been allotted to them by the State of Alaska. M. Edward King, an area guide since the early 1960s, was deprived of more than 300,000 acres from Area 9-43, over which he had had exclusive jurisdiction. Those 300,000 acres, located between the old monument boundary on the south and Nonvianuk and Kulik lakes on the north, became part of Katmai National Park when ANILCA was passed, and thus remained off-limits. [68]

Ray Loesche was another guide who lost territory. Loesche was a licensed big game hunting guide who had been operating across the Alaska Peninsula since the mid-1950s. His camps were located on Upper Ugashik Lake and Alinchak Bay. Prior to the expansions, he had hunted extensively all around the park perimeter: in the Douglas River drainage, the Kamishak and Strike Creek drainages, the areas surrounding Kulik and Kukaklek lakes, and the Kejulik River drainage. All but the latter area were eliminated by the 1978 expansion. With the passage of ANILCA, only the Kukaklek area was reopened to hunting. [69]

Ben White, who represented Far North Guide and Outfitters, was yet another victim. White, who had an exclusive permit to hunt in Area 9-80, had been leasing Battle Lake Camp from Wien since 1971 if not before. [70] Most of his hunting area was eliminated by the 1978 monument expansion. Then, with the passage of ANILCA two years later, he regained control of most of his hunting area because it was designated part of Katmai National Preserve. Alaska lands legislation, however, does not appear to have impinged upon his operation. According to advertisements in Alaska Magazine, the elderly White did not promote hunting at the camp after 1975, and his operation appears to have shut down in 1977. [71] Battle Camp reopened in 1980 and 1981 under Wien's direct control, but guided hunting was not one of the featured attractions during that two-year period. [72]

Several other hunting guides were also affected by the 1978 monument expansion. At the southern end of the monument, around Alinchak Bay, boundary changes deprived Mario Salimchak of part of his hunting territory, while off to the northwest, Jim Cann also had his hunting area reduced. Others who had led guided hunts within the newly-expanded part of the monument included Denny Thompson, Reinhold Thiel, and Jack Myers. As of 1972, 15.5% of all Alaska Peninsula guides who registered bear camps located those camps within areas proposed for expansion. These camps were well-placed, because 42 brown bears (15.3% of the total peninsula harvest) were taken that year within the same area. [73]

Hunting was one of several activities which brought guided visitors onto national park lands without permanent structures being built. Therefore, hunting was regulated by Commercial Use Licenses beginning in 1981. Thereafter, the NPS and the state shared jurisdiction over the territory allotted to hunting guides. The Alaska state government, through its Guide Licensing and Control Board, controlled the allocation of hunting districts (both exclusive and joint-use districts) throughout the state. But the National Park Service controlled access and land use within areas under its jurisdiction. [74]

Because relative few hunting permits encompassed the lands included within Katmai National Preserve, a small number of companies conducted hunts during the early and mid-1980s. Commercial Use License records indicate that four companies obtained sport-hunting CULs between 1980 and 1988. Two of those four did not take advantage of hunting privileges. Ben White's Far North Guide and Outfitters, mentioned earlier, held an exclusive state permit for Area 9-80. Even though the size of the guide area which remained after the passage of ANILCA was substantially smaller than had existed until 1978, it still encompassed more than three-fourths of the preserve. White obtained a CUL for use of the territory from 1981 through 1984. NPS records indicate, however, that he never exercised his state hunting permit during the 1980s, an action that incurred the wrath of the state's Guide Licensing and Control Board. [75]

Another inactive guide was M. Edward King, owner of King Flying Service. King had lost most of his hunting rights in 1978; in 1980, however, he regained the right to hunt in that portion of the preserve located south of the Nonvianuk River. King apparently conducted several hunts in that area during the 1980s; due to a lack of accurate maps, however, Katmai staff did not feel that his area was within the preserve boundaries. Shortly after King's death in early 1988, his son Jay requested that the company's CUL for the area be amended to allow sport hunting. In May 1989, park staff belatedly recognized the company's legitimate right to hunt within the preserve. [76]

The other two CULs were active on a limited basis. Between 1983 and 1988, Katmai Guide Service was given permission to invite hunting parties into the "open" portion of the preserve (that is, that part of the preserve which had not been assigned by the state to another guide). The company's activity in the area, however, was limited to three moose-hunting trips in 1983 and 1984. Rainbow River Lodge, operated by Chris Goll and Marie Toler, used the area more extensively. In March 1985, guide Chris Goll obtained Ben White's state permit to Guide Area 9-80. The permit has been used at various times thereafter for the May bear hunt, the August caribou hunt, the September moose and caribou hunts, and the October bear hunt. [77]

On October 15, 1988, the system under which the state allotted its hunting areas was rent asunder. The Alaska Supreme Court wrote an Opinion in response to a suit filed by guide Kenneth D. Owsichek. That Opinion declared it unconstitutional for an appointive body (such as the Guide Licensing and Control Board) to assign exclusive commercial hunting areas. [78]

The abolition of such a system opened the door to an unrestricted number of hunting parties being allowed access to each of the state's national preserves. To forestall such a consequence, the Service quickly moved to establish an interim program for guided hunting. That program involved the issuance of concession permits, the number of which was limited to that which had existed previously. The concession permit system was intended to last only until the state could reestablish a sanctioned system. But such a system has not yet been implemented; therefore, the Service's interim system remains in force today. [79]

To guarantee the same degree of exclusivity which they had previously enjoyed, a new relationship had to be established between the NPS and the new permit holders. The permits, which were designed during the winter and spring of 1989, demanded a significantly stronger regulatory framework. It also required higher fees: $500 in 1989 and $1000 in 1990 instead of the $75 annual fee required of CUL holders. [80]

Companies which had held active CULs for sport hunting during the 1988 season were given an opportunity to apply for 1989 Concession Permits. At Katmai, two companies qualified. The Rainbow River Lodge, which held a CUL since 1985, obtained its permit in May 1989. The King Flying Service, which had not conducted hunts in recent years but had applied for a CUL in May 1988, obtained an approved permit in September 1989. [81]

Since that time other guides have tried to enter the hunting business in the preserve, but Rainbow River and King Flying Service have remained the only two businesses with valid permits. [82] Both companies obtained "satisfactory" ratings in 1989 and 1990 for their adherence to the conditions listed in the concession permits; King Flying Service gained a positive rating in 1989 even though it conducted no hunts that year. Both were awarded one-year permit extensions in January 1991. The new permits were similar to those issued in 1989, the only major difference being that the cost of the permit was changed from a flat fee to a $500 fee plus one percent of the guide's annual gross receipts. [83]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

katm/tourism/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 13-Oct-2004