|

Katmai

Tourism in Katmai Country |

|

CHAPTER 1:

EARLY HISTORY OF KATMAI NATIONAL MONUMENT

Katmai National Monument was created in 1918. Although those responsible for the creation of the monument foresaw its commercial possibilities, the area's remoteness caused it to be largely ignored for over thirty years. The onset of World War II, and the growing interest in the territory's sport fishing possibilities, reduced that remoteness. During the immediate postwar period the National Park Service, which has allowed the park to remain dormant, came under increased pressure to establish a presence in order to reduce illegal activities and justify park values. One of the people who knew the Katmai area best during this time was Ray Petersen, a one-time bush pilot who had recently organized the dominant airline in southwestern Alaska.

Development of the Katmai Country Before

1950

President Woodrow Wilson, through Proclamation No. 1487, established Katmai National Monument on September 24, 1918. The monument was created to protect some 1700 square miles of southwest Alaska. The landscape included was deemed to be "of importance in the study of volcanism," and in addition was felt to be of "popular scenic, as well as scientific, interest for generations to come."[1]

One of the world's largest volcanic explosions had rocked the area beginning June 6, 1912. To investigate the extent of its devastation a scientific team, headed by U.S. Geological Survey geologist George C. Martin, began exploring the area in the summer of 1914. The expedition was sponsored by the National Geographic Society (NGS). The following year, Ohio State University botanist Robert F. Griggs began the first of five annual trips to the area. The wonders encountered on the Martin and Griggs expeditions were published in the National Geographic Magazine, and the publicity generated from those expeditions was in large part responsible for the creation of Katmai National Monument. [2]

The final NGS trip into the area took place in 1930. The course of that trip led Griggs and his party west to Naknek Lake and the Brooks Camp area, which were beyond the western boundary of the monument. Expedition members were so impressed by the primeval countryside and the large numbers of brown bears that efforts began to expand the monument westward.[3] As a result, President Herbert C. Hoover issued Proclamation No. 1950 on April 24, 1931, which more than doubled the size of the monument. The enlarged monument, 4214 square miles in extent, was the largest unit in the national park system.[4]

During his 1916 expedition, Griggs wrote that the wonders of the Katmai district "must be made a great national park accessible to all the people, like the Yellowstone." Despite the creation of the monument and the volcanic and scenic wonders it offered, however, few visited the area before World War II. The Katmai country was largely undeveloped and distant from the major shipping routes. Because of the high expense of travel and the lack of accommodations, few tourists were aware of its existence. Alaska interests had decried the establishment of the monument because of its potentially dampening effect on economic development; Governor Thomas Riggs, for instance, remarked that "Katmai Monument serves no purpose and should be abolished." [5]

A few early efforts were made to develop tourism to the area. Robert F. Griggs, discoverer of Geographic Harbor along the Pacific coast, noted that it would be easy for steamers to land people nearby. He added that "a few miles of road [from the harbor to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes] will render the valley as readily accessible as the geysers of Yellowstone National Park." [6] Shortly thereafter, the Alaska Road Commission responded to Griggs's suggestions by proposing the thirty-mile road, and Governor Scott Bone recommended its construction in his annual reports for 1922 and 1923. He soon learned, however, that because the proposed route traversed a large area of fresh ash deposits (a material which, witnesses noted, had the consistency of either snow or ground coffee) it was too unstable to support road traffic. Bone also learned that the budget for all of the country's national monuments was only $12,500. The Department of the Interior noted, therefore, that it was "not in a position under present circumstances to lay out any sort of development program for Katmai." The road was never seriously considered again, although governors' reports for years afterwards bemoaned the monument's lack of access. [7]

Despite the difficulties in reaching the monument, a few tourists dribbled in before World War II. In 1923, a party of forty spent two weeks exploring the area. As part of their trip, they hiked Mount Katmai. Seventeen more visited in 1924. Throughout the 1920s, Kodiak advertised itself as the outfitting headquarters for trips to the monument, perhaps because it had been the jumping-off point for the various National Geographic Society trips to the Valley of the Ten Thousand Smokes. Tourists heading there crossed the forty-mile Shelikof Strait in small boats. The Alaska Railroad also offered to arrange trips to the monument. [8]

To provide visitors aerial views of the Katmai country, Anchorage Air Transport offered a one-day tour in 1929. For $265, the company offered to fly visitors into the still-active Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and provide them eight hours for exploration and sightseeing. The success of the company's advertising is not known, but in the early 1930s Frank Dorbrandt, a pilot who flew for Anchorage-based Pacific International Airways, took several parties into the volcanic country. Robert Ellis (of Alaska-Washington Airways) and other charter operators also visited the area during the early to mid-1930s. [9] By 1940 John Walatka, a pilot for Bristol Bay Air Service, had also become familiar with the monument. [10]

|

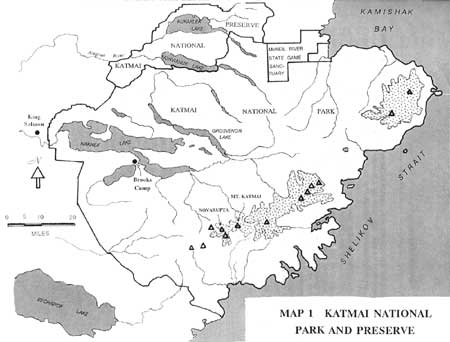

| Map 1. Katmai National Park and Preserve (overview map) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Service showed almost no interest in Katmai in its early years. The monument, officially closed to the public because no staff were available to protect it, [11] was managed as an adjunct to Mount McKinley National Park (now Denali National Park and Preserve). But the first NPS personnel did not enter the monument until 1937 when Grant Pearson, the Chief Ranger for Mount McKinley National Park, flew over portions of it. [12] It was not until three years later that Victor Cahalane and Frank T. Been made the first extensive NPS investigation. Cahalane, an employee of the agency's Biological Survey, and Been, the Superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park, spent most of September 1940 walking, boating, and flying over the monument. [13] Been and Cahalane recognized the tourist potential of the area. Over the short term, they felt that "its remoteness precludes it becoming a tourist center for many years," but noted that "when the beauty of the Naknek, Brooks, Grosvenor and Coville Lakes becomes known and the splendid trout fishing becomes recognized, sportsmen may go to the lakes." [14]

Prior to the Been-Cahalane expedition, government personnel were already stationed at the monument. Personnel of the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, in the U.S. Department of Commerce, had built temporary quarters on the eastern shore of Brooks Lake, pushed a tractor trail to the south side of the falls, and erected a weir at the outflow of Brooks Lake. The present Fish and Wildlife Service building was built a year later. [15]

Usage of the monument rose sharply during World War II. In 1941, the U.S. Army Air Corps established Naknek Air Base (which was renamed King Salmon Air Station in the 1950s). Construction and military personnel soon discovered that the nearby waters, because of their temperature and purity, offered superb sport fishing possibilities. [16] Military authorities reacted by establishing two rest and recreation camps nearby. Rapids Camp (called Annex No. 1 by the Air Force) was located at the foot of the Naknek River Rapids, five miles southeast of the base, while Lake Camp (Annex No. 2) was located at the west end of Naknek Lake, seven miles to the east. [17] Naknek River and the western end of the lake, therefore, were subject to heavy fishing pressure for the remainder of the war, but many plane loads of servicemen also flew into Brooks River, the Bay of Islands and other fishing spots, where they reportedly pulled "thousands upon thousands of trout" from the water. The Service, lacking funds for a ranger staff, was powerless to stop the onslaught. All it could do was arrange with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (the successor to the Bureau of Fisheries) for the enforcement of hunting and fishing regulations. [18]

Word soon leaked out about the fishing potential of the Katmai country, and before long civilians demanded trips into the area as well. As early as 1942, the Ray Petersen Flying Service had begun taking superintendents from Bristol Bay canneries into the Brooks Camp area on recreational fishing trips. [19] Bud Branham, a fisherman who flew out of Kodiak and Fairbanks during the war, was another who visited the monument. The pilots and clients passed the word along to others in southwestern Alaska, and by the end of the war a smattering of fishermen throughout the Territory had heard of Katmai's large, plentiful rainbow trout. [20] Petersen himself piloted many of those flights; as he noted years later, "during [World War II] I fished all of the areas where the concession camps and lodges are now located. It was recognized at that time that these were the choice rainbow streams in Alaska and that the entire [Katmai] area was prolific in many other types of sport fishing." [21]

The Service responded to the new popularity of the park by attempting to establish a presence. Several times during the decade regional officials submitted proposals to fund a part-time ranger, but all attempts were unsuccessful. [22] In addition, officials began laying out plans intended to stimulate visitation to the monument. In 1942, for example, the regional director urged the construction of ten shelter cabins in the monument. [23]

Another idea which surfaced that year was a proposal to restore the Native village of Savonoski, which had been buried during the 1912 eruptions. Frank T. Been, Superintendent at Mount McKinley National Park, felt the project was timely, inasmuch as "the construction of the barabs (native houses) is still readily evident," and urged that $25,000 be appropriated for the task. He further noted that the "restoration should be...done by natives and according to native standards" for reasons of cost as well as cultural continuity. Acting Regional Director Herbert Maier, however, held the project in abeyance, noting that "there is little justification for including it in the program at this time." [24]

The NPS began to develop even more ambitious plans as well. By early 1946, officials at Mount McKinley National Park had commenced planning the locations of a possible Katmai tourist lodge, boat docks, trails, patrol cabins and administrative sites, and had made preliminary inspections of the park with those questions in mind. The location of the proposed sites, however, remains a question mark, and none of the plans came close to being implemented, perhaps because high officials in the Interior Department felt that "there has not been sufficient tourist travel in Alaska to justify the appropriation of Federal funds to provide facilities in this location." [25]

Commercial Access to Katmai,

1945-1950

Some of the first to hear about the excellent fishing in the area were the pilots which serviced the nearby canneries, mines, and villages. The northeastern end of the Alaska Peninsula, distant from Alaska's rudimentary highway network, was supplied by sea as well as by air. Private shipping companies, including the major fish packers, plied a healthy trade between the Lower 48 and the various Bristol Bay canneries, while the Alaska Steamship Company served scattered villages on both sides of the peninsula. Shipping companies, however, had neither an interest nor a means of access to the Katmai sport fishing country. Therefore, area pilots were largely responsible for bringing fishermen into the area.

One of the best known pilots serving that area was Ray Petersen. Petersen, a veteran bush pilot, was born in York, Nebraska, on August 10, 1912. He had been raised on a ranch in Wyoming but had learned to fly in 1929 in the Chicago area. He headed west to Bellingham, Washington, in 1933 and arrived in Alaska in April 1934. [26] He worked for Star Air Service (a predecessor to Alaska Airlines) beginning that September; he served the Lucky Shot Mine north of Anchorage in addition to a scattering of trappers and prospectors. The following February, he began flying for Marsh Airways between Anchorage and Bethel, with occasional trips out to the platinum and iridium mine at Goodnews Bay. By the end of that summer he had become a founding partner in Bethel Airways. His work with Marsh and Bethel airways, while brief, was a portent of things to come, because he spent the rest of his career developing the aviation industry in southwestern Alaska. [27]

A major break came in 1937 when he obtained a contract to haul goods to and from the mine at Goodnews Bay. Consistent work allowed him to form the Ray Petersen Flying Service (based in Bethel) that year, and for the next several years he carried goods from Anchorage to retail outlets, government offices, and individuals in the Lower Yukon and Kuskokwim river regions. [28] The Goodnews Bay mine owners, however, remained a consistent source of much-needed capital, and hauling miners and company supplies proved to be a consistent source of income. By late 1941, he had earned a modicum of prosperity. He moved to Anchorage just before the outbreak of World War II. [29]

Once the war began, the planes owned by many Alaskan pilots were sometimes commandeered to haul military supplies. But Petersen flew primarily for civilian purposes. He flew packed fish out from the Bristol Bay canneries and continued to serve the mine at Goodnews Bay, which remained open because both platinum and iridium were classified as either critical or strategic minerals. [30]

As the war progressed, Petersen and others recognized that Alaska aviation was changing. Increased business, the introduction of scheduled service and improved navigation aids all demanded the purchase of larger aircraft, and only through consolidation could the capital be raised to acquire the necessary planes. In 1943, therefore, Petersen purchased the Bristol Bay Air Service, operated by Bert Ruoff, and the Jim Dodson Air Service, which served Ruby, Beaver, and adjacent points out of Fairbanks. [31]

Before those purchase agreements could be approved, however, Petersen and several other airline companies decided to amalgamate. Included was the Ray Petersen Flying Service, owned by Raymond and Marie Petersen and Glen Dillard; Jim Dodson Air Service, owned by Jim and Mildred Dodson; Northern Airways, owned by Frank and Hazel Pollack and Terrence McDonald; Walatka Air Service, owned by John Walatka; Nat Browne Flying Service, owned by Nathan C. Browne; and Northern Air Service, owned by Robert and William Miller. [32] They entered into a corporate organization agreement on October 22, 1945; three months later, on January 30, 1946, the carriers formally applied to the Civil Aeronautics Board to create Northern Consolidated Airlines (NCA).

On May 8, 1947, the CAB approved Petersen's two airline purchases as well as the four-company consolidation. By that time, NCA had purchased several war-surplus DC-3s, its first large planes. [33] Peterson, the major shareholder, was elected president of the new airline, while Pollack and Miller served as the first treasurer and secretary, respectively. Petersen was to remain at the helm of the company as long as it operated, a total of more than 20 years. [34]

Northern Consolidated Airlines thus emerged as a major carrier for most of southwest Alaska. Although it did not offer service between Anchorage and Fairbanks, it used those two bases as jumping-off points to villages and towns along Bristol Bay, the Kuskokwim River, and along the Bering Sea between Cape Romanzof and Cape Newenham. It also served a few villages along the middle Yukon River and in the Circle-Fort Yukon area. In all, the line boasted three mail routes and served some 45 villages on a regular basis. It also had irregular service authority over a large portion of western and southwestern Alaska. [35] Competitors in its service area included Wien Alaska Airlines, Reeve Airways (later Reeve Aleutian Airways), Alaska Airlines, and Pacific Northern Airlines. [36]

Because of its network, Northern Consolidated was in an excellent position to serve the Katmai area. By 1950, the line was the only carrier which provided direct service from Anchorage to Naknek Air Base (now known as King Salmon), as well as to nearby Koggiung, Egegik, and Igiugig. Two larger airlines, however, also stopped at the same four spots. Pacific Northern Airlines, which boasted the route certificate from Anchorage to Seattle, possessed the mail contract to the four locations. Alaska Airlines, holder of the lucrative Anchorage-Fairbanks route certificate, provided added competition. [37]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

katm/tourism/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 13-Oct-2004