|

John Day Fossil Beds Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Seven:

PALEONTOLOGICAL EXPLORATION (continued)

Early Twentieth Century Research

In the twentieth century a new generation of collectors and writers worked with the specimens of the upper John Day region, expanding knowledge of the relationships between vertebrate faunas and the basin's stratigraphic sequence. John Campbell Merriam of the University of California, subsequently president of the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D. C., began his fieldwork in 1899. The first University of California expedition included Merriam, its director, Loye H. Miller, a naturalist, F. C. Calkins, geologist, Leander Davis, local guide and (by then) sawmill operator out of Baker City, and George B. Hatch, a hunter and fisherman. The party traveled via The Dalles Military Road into the Bridge Creek area. The men established a base camp at Allen's Ranch, noted as six miles south of the mouth of Bridge Creek and two and one-half miles southeast of the wagon road. The group made at least two more camps in Turtle Cove to work the John Day Formation (Anonymous 1899). Merriam's work concerned the relationship of fauna to geology. His discerning observations led to descriptions of several salient features of the deposit areas: river terraces, Columbia lava, John Day Series, and the Clarno, Mascall, and Rattlesnake formations.

Merriam's integration of fauna and geology influenced his students, Eustace Furlong, Chester Stock, and Ralph Chaney who mounted additional expeditions in 1900, 1901 and 1916. They published a collaborative work, "The Pliocene Rattlesnake Formation and the Fauna of Eastern Oregon" (Merriam, Stock and Moody 1925). Erling Dorf of Princeton University recalled in 1979 that he had served as an assistant for Ralph W. Chaney in the Mascall and Clarno formations, "probably in 1926 or 1927," (Dorf 1979).

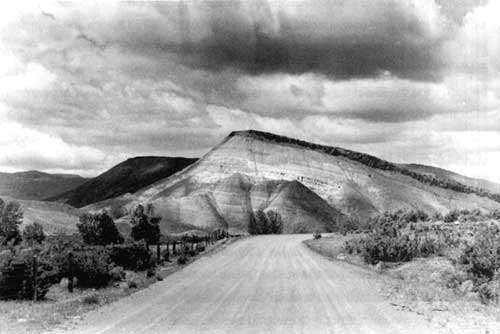

Fig. 56. View of Carroll Rim on Bridge

Creek, Painted Hills Unit (OrHi 57789).

Geologist Ralph Chaney devoted much of his field time and research to the flora of the lower John Day Formation found in the Bridge Creek region. "It soon became clear," noted J. Arnold Shotwell, "that this basin provided an ideal set of circumstances for sequencial [sic] floristic studies and in the next forty years Chaney took advantage of these to produce a series of highly significant papers providing the basis for much of modern paleobotany" (Shotwell 1967: 13). Chaney's works included "Quantitative Studies of the Bridge Creek Flora" (1924), "Geology and Paleobotany of the Crooked River Basin" (1927), and "The Ancient Forests of Oregon" (1948).

In 1906 the University of Kansas sponsored an expedition to the John Day region. C. E. McClung, Martin, Baumgartner, and Hoskins — members of the Zoology Department — crossed the Blue Mountains to the John Day on July 1 and established a base camp at Turtle Cove. "Almost all colors of the rainbow may be seen, but the prevailing ones are chocolate red and pea-green," wrote McClung. The Kansas contingent worked diligently. "It is a very difficult matter to remove the bones in good condition because of the lack of homogeneity in the matrix," observed McClung, but he hastened to add that the bones were "in an excellent state of preservation and make beautiful specimens." The specimens went to the holdings at the University of Kansas (McClung 1906: 67-70).

During the summers of 1925, 1930, and 1934 the California Institute of Technology mounted expeditions to the John Day region. In 1940 its students and professors joined an expedition with the Carnegie Institute of Washington, D.C. The specimens were transferred in 1959 to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (Whistler 1979).

Deposits near Clarno, Oregon, provided important paleobotanical information. The deposits were first discerned about 1890 and led to the publication of "Fossil Flora of the John Day Basin" (Knowlton 1902), a monograph discussing twenty-two forms of leaves. In 1942 Thomas J. Bones commenced his paleobotanical work in the Clarno deposits. Bones later stated that over fifty different genera had been identified but that "many hundreds of species are now extinct, rendering identification to modern genera difficult to impossible" (Bones 1979: 5). In 1942, dedicated amateur geologist Lon Hancock found a fossil tooth in the Clarno "nut beds" along Pine Creek. R.A. Stirton of the University of California soon identified the tooth as from the rhinoceros Hyrachyus in the first account of animal remains from the Clarno beds (Shotwell 1967: 14). In 1956, Hancock discovered mammal fossils about one mile from the nut beds, and subsequently excavated a large site now known as the Hancock Mammal Quarry. Investigations at the mammal quarry continued into the 1980s, yielding a highly diversified fauna (Fremd, Bestland, and Retallack 1994).

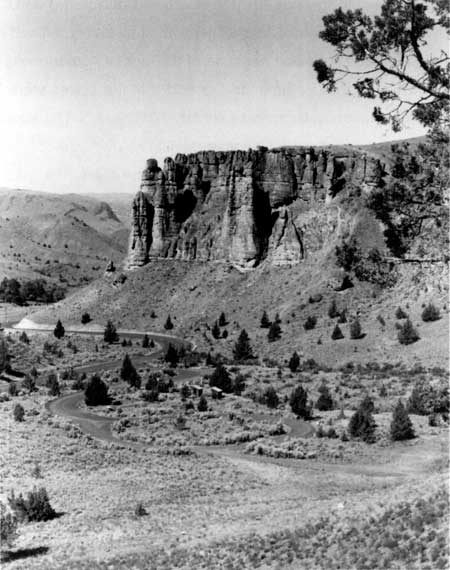

Fig. 57. View of eroded rock palisades

at Clarno Unit (OrHi 101197)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/hrs7b.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002