|

John Day Fossil Beds Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Four:

SETTLEMENT (continued)

Subsistence Living

For decades, those who settled in the John Day country, or those who were born into families residing in that region, shared basic elements of a recognizable lifestyle. Almost all, particularly those living in rural areas but even those living in small towns, engaged in unceasing labors for survival. They lived close to the land, knew and used its potentials, and confronted numerous challenges. Weather — the heat of summer and bitter cold of winter — and flash floods, lightning strikes, falling rocks, forest and prairie fires, rattlesnakes, and rabid animals were realities they had to confront and endure. Illnesses and lack of professional medical care catapulted home doctoring and nursing to a higher significance than in other parts of the region. Life, for a long time and for some a lifetime, was a scramble and a test.

Isolation was a common feature for the scattered residents of Grant and Wheeler counties. Until the 1910s, most of the region was linked to the outside world only by a system of trails and rudimentary wagon roads. Lack of electricity and telephone lines perpetuated isolation far longer than in other areas. Residents used candles, kerosene lamps, carbide lamps, and their own electrical plants. Larger ranches such as that of James and Elizabeth Cant by the 1910s had their own generators to provide a few hours of electricity each day to run shearing equipment, operate electric lights or, by the 1920s, to power a radio. "Yeah, we spent lonely days," recalled Rhys Humphreys, "but we didn't know any better. It was lonely here; the only people that we ever visited was neighbors" (Humphreys 1984a: 4, 21). Isolation for some was a function of labor. The dozens of men who tended sheep and prospectors and miners frequently lived alone or far from society for days and weeks.

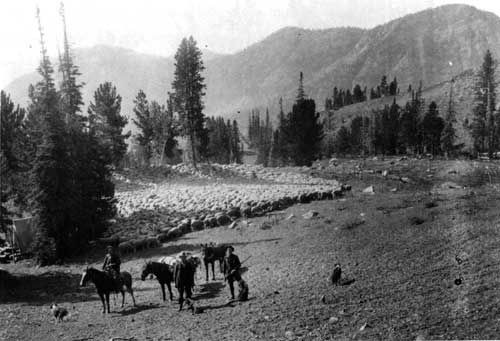

Fig. 17. Herders with flocks at summer

pasture in the mountains of Eastern Oregon, ca. 1915 (OrHi 5,

139).

Daily labors in an era of subsistence living were often gender specific. Women customarily carried nearly total responsibility for maintaining the household and child-rearing. Their tasks — backbreaking and monotonous — involved cooking, washing, mending, making clothing, food preservation, and cleaning. They planted and weeded vegetable gardens, drove away birds and rabbits, picked foodstuffs, dried and parched foods, canned dozens of pints and quarts of home-grown fruit and vegetables, and recycled materials. Their fingers turned old clothing into quilts and rag rugs. They watered stove ashes in hoppers to make lye to process fat and bacon grease into soap. They raised chickens and collected eggs and milked cows and made butter. Any surpluses they carried to town to barter for dry goods and staples. They worked constantly and lived frugally (Jackson 1984: 24-25; Murray 1984a: 64).

Fig. 18. Ranch house of the Henry

Wheeler family, on SR 207 between Service Creek and Mitchell, one mile

south of Twickenham junction Ca 1910 (Courtesy Fossil Museum)

Men shouldered other responsibilities. They cut, hauled, and stacked wood to fire cook stoves and heat dwellings. In winter they sawed blocks of ice and hauled them to insulated ice houses for use in subsequent months for food preservation and for cooling beverages. They dug cellars, lined them with stone, and filled bins with potatoes, turnips, and apples wrapped in newspapers. Hard labor duties for men included stock tending, sheep shearing, branding, fence construction and maintenance, building houses and barns, blacksmithing, moving herds to markets, and digging ditches. Irrigation was critical in an arid environment. Men hand-dug canals and ditches, planted willows, locust, and poplar along their courses to stabilize their banks, and worked each year to clean the ditches of slide debris and weeds and to repair washouts. Men repaired wagons, harness, mowing machines, plows, harrows, and tools. They hauled foodstuffs in wagons, on pack teams, in touring cars, and in trucks. They changed oil and gaskets, repaired flat tires, and rebuilt engines (Cant and Cant 1984: 21-22; Jackson 1984: 22; Murray 1984a: 38, 60-66; Murray 1984b: 2).

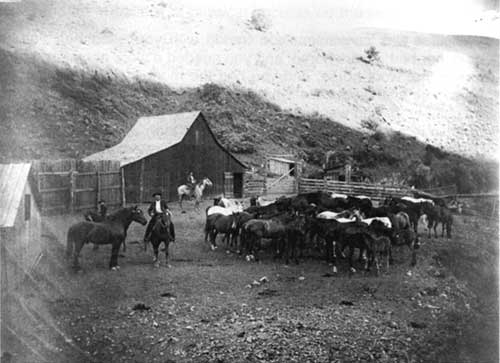

Fig. 19. Men at work on the Bob Wright

on the Parrish Creek Ranch, n.d. (Courtesy Fossil Museum).

Men also contributed to the family diet by hunting, fishing, planting, and pruning fruit trees as well as butchering cattle, sheep, and hogs. They constructed smokehouses and tended fires to preserve meat as jerky and hams. Some worked with their wives to stuff intestines with ground meat fragments and spices to make sausage or head cheese. They hauled wheat to grist mills and brought home flour and corn meal. They tilled the vegetable patch and helped guard the plantings from hungry deer and rabbits. They tanned hides and bartered with Indians from the Warm Springs Reservation for gloves and moccasins. When they lacked cash, a common occurrence, they bartered labor, goods. and livestock for necessary commodities, tools, or food (Cant and Cant 1984: 28; Humphreys 1984b: 25; Murray 1984a: 29-30).

John Murray, a lifetime resident of the area, described the common barter system:

Well, if it was convenient you traded with your neighbor, yes. If your neighbor had a work horse, and you needed a work horse, and he wanted to sell that work horse, and you had the money, you could buy the work horse, or vice versa, or whatever. Or if you had an extra piece of machinery, or you wanted to buy a piece of machinery, and he happened to have it, and if you could buy it cheaper than you could buy it new, why you bought it because you didn't have any money anyhow (Murray 1984a: 29).

The residents of the upper John Day region were perhaps less affected by the impact of the Great Depression. Most lived frugally and had the means to survive through their own hard work. Many raised or procured large amounts of their own foodstuffs. None had high expectations. In several instances young adults remained at home a few years longer, securing housing from their parents and helping work the ranch. The Grant County Bank in John Day, a central point of deposit and loans for many, was shored up by the Oliver family and others and remained solvent, closing only for the national Bank Holiday. Its stability provided a security for the residents of the region not experienced by millions of Americans in other parts of the country (Humphreys 1984a: 26; Murray 1984a: 37).

Subsistence living demanded hard work but it engendered satisfaction. Through the first half of the twentieth century, the rural population of Grant County and Wheeler County remained sparse but relatively constant (Mark 1996: 28). Those who stayed were satisfied with their lot, and considered living in the region with its stark beauty and personal freedom a sufficient reward for confronting its daily challenges.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/hrs4h.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002