Administrative History

|

Hopewell Culture

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER SEVEN

Maintenance of Mounds and Park Infrastructure (continued)

| History of the Physical Plant |

The small MISSION 66-era visitor center and museum building became the monument's key visitor services point following its 1960 opening. To accent the modern complex, a new stone entrance gate and sign replaced the original configuration in October 1961. One of the earliest "glitches" concerning the new construction concerned its septic tank in that it proved to be too close to the ground's surface. This resulted in turf failure and planting bushes to screen visitor's views of the bare spot from the observation deck. [39]

Water seeping along the edges of the visitor center's skylights came in September 1962. While the building's original contractor made those repairs, no one anticipated that the flat-designed roof would continue to leak so badly throughout its lifetime. Two years later, Superintendent Riddle reported that leaks over the restroom areas had to be patched and the "Other Outstanding Mounds" exhibit required leak-related repairs. Laborers replaced the fifteen-year old roof in 1975 and new skylights were also installed, but leaks persisted. Park maintenance continued to perform roof-patching chores each season. Exasperated by delays working through the Denver Service Center to discover the sources of water leaks, Superintendent Fagergren cancelled the assistance request by stating that his own staff plugged the suspected entry points. [40]

So stingy on space was the visitor center that it lacked sufficient storage areas for maintenance supplies and small equipment. In 1963, maintenance workers erected for such a purpose a small metal building measuring both six-foot, eight-inches wide and long by eight-feet high at the visitor center's northwest corner. Regularly supplied hot water did not arrive until mid-1971 when workers installed a small hot water heater in the utility space between the two restrooms. An incredulous Bill Birdsell exclaimed upon the new addition, "Having hot water available for building maintenance is very helpful, and at least we are not having to heat scrub water in the office coffee-pot!" [41]

In October 1977, the Denver Service Center prepared a task directive for expansion of the visitor center as part of the Bicentennial Land Heritage Program. The expansion accommodated an additional 2,900 square feet of space as follows:

| artifact basement storage and library | 400 square feet |

| auditorium | 1,200 square feet |

| interpretive workspace | 150 square feet |

| office space (six interpreters) | 440 square feet |

| stairs, mechanical, circulation | 700 square feet |

According to the directive, construction drawings were to be generated in 1979. [42]

Appropriations for the expansion failed to materialize and construction planning documents were not prepared. In the vain hope that dropping the auditorium from the request might move the project up to a higher priority for funding, Fagergren believed that slashing the cost might make the project a reality. While the January 1970 Interpretive Prospectus had first recommended an auditorium, Fagergren deemed a late 1970s video presentation in the museum as sufficient and stressed more basic needs as essential. Fagergren's first concern was to provide a stable environment for the archeological collection. His second consideration envisioned providing an external area for interpretive events during inclement weather by using the patio, the spot for the proposed auditorium, as a covered veranda. His third basic need involved having adequate administrative work space for park staff. [43]

Funding for the necessary additions did not arise. A critical over-crowding of the administrative office area came in May 1979. A new floorplan for the compact twelve- by twenty-four-foot office called for new furniture to accommodate five permanent and three seasonal employees. Funding from the retiring maintenance leader's lapsed position in the fall of 1979 allowed the purchase of space-efficient furniture, but office conditions remained cramped in the visitor center for the next nine years. [44]

Visitation continued to grow and increasing numbers of heavy vehicles such as school buses and large touring coaches needed to be accommodated, but overflow parking resulted in unsightly ruts and damage to the lawn. No one wished to expand the already sizeable lot. A compromise solution involved converting a 3,000 square foot grassy area to serve as an overflow lot. The informal area received stability for parking purposes by installing a pattern of "turfstones" in 1981. [45]

After years of applying patching material to fix the sieve-like visitor center roof, the National Park Service awarded a roof replacement contract in 1984 to Rebel Roofing Company of Colonial Beach, Virginia. It represented the building's third and last flat roof. Contractor delays resulted in one time extension and work began on July 30 during the middle of the heavy visitation season and concluded five weeks later. Not satisfied with the quality of work, particularly after a new leak developed, Omaha contracting officials granted another contract extension until the end of November. When attempts to find and stop the leak failed, the agency declared Rebel Roofing in default on December 24. [46]

The defaulted roof contract yielded negotiations locally for a new contractor to conduct repairs. On March 25, 1985, Alexander Roofing Company of Chillicothe removed roofing material over the suspected leak, exposing damage over a 214 square foot area. Repairs were finished the following day. [47]

Figure 67: The flat visitor center's roof perpetually leaked, despite repeated attempts to repair it. Extensive interior water damage and disturbance of an asbestos ceiling necessitated a radical redesign. (NPS/September 1984) |

The same month that the defaulted roof contract occurred, the monument learned more bad news. After consulting with the Ross County engineer, Ken Apschnikat reported severe splitting at the base of the four outside steel beams supporting the visitor observation deck. While there was no immediate danger of structural failure because there was no evidence of bowing or bulging at any weak points and the four inside supports were undamaged, the condition called for a solution. Apschnikat hoped that it would also contribute to halting the water intrusion problem.

As early as August 1981, the park had requested funding to replace the aging concrete and steel observation deck. Freezing and thawing contributed to the concrete slab's deterioration and the steel I-beams began rusting as water penetrated through hairline cracks. In order to prevent pieces of the rusted metal ceiling falling on visitors walking beneath the deck, maintenance workers began applying temporary patches to prevent the hazard. Such efforts did nothing to halt rusting caused by trapped moisture between the concrete slab and metal ceiling. In 1983, a contractor replaced the concrete deck, made necessary repairs, and installed heated floor mats to eliminate freezing and thawing. [48]

Roof woes resumed on February 1, 1988, when heavy rains pooled water on the visitor center roof's northeast corner, causing extensive water damage to the interior walls, ceiling, and floor coverings. Damage concentrated in the superintendent's office south to the outer administrative office. It raised new fears of catastrophic ceiling failures and releasing deadly asbestos fibers into the work areas. Emergency repair work included installing a rubber membrane over the building's northeast corner. [49]

Figure 68: The pitched, red metallic roof gave a dramtic facelift to the MISSION 66-era visitor center. (NPS/Rebecca Jones, fall 1996) |

The incident prompted calls for a radical redesign of the flat roof, but not before another pooling episode on April 1, 1990, in the same area brought water cascading down on the park's library. Moved from the maintenance utility building's basement following conversion of the residence to the new administrative offices, the library had returned to the newly spacious visitor center only to be met with a third of the shelved volumes suffering water damage. After air-drying the soggy books, park maintenance placed the entire archive in boxes and moved it for safekeeping to the administration building until permanent roof repairs were made. [50]

In late 1990, a contract called for four alternative design concepts to retrofit the failed roof. Selecting the preferred design, the agency awarded the contract on October 7, 1991, for a raised metal seam roof to shed rain and snow to Brothers Construction Company of Columbus, Ohio. Difficulties in securing the required bonds delayed construction work until mid-1992, and all the while employees were using buckets and plastic tarps to prevent further interior damage until the work concluded later that year, including removal of the hazardous ceiling. [51]

Because the park budget could no longer endure the $550 annual payment to the telephone company to maintain the public telephone booth adjacent to the visitor center parking lot, Bill Gibson requested it be removed on January 4, 1990. Local workers at the Veteran's medical center and prison employees used it to make personal phone calls, and only occasionally did non-local park visitors make use of it. Gibson reasoned the annual expense could not be justified, and visitors with legitimate calling needs would be permitted to use agency telephones inside the visitor center. When no action resulted, Gibson learned that the company released the monument from its payment obligation and wanted the telephone booth to remain in place until its removal in 1993. [52]

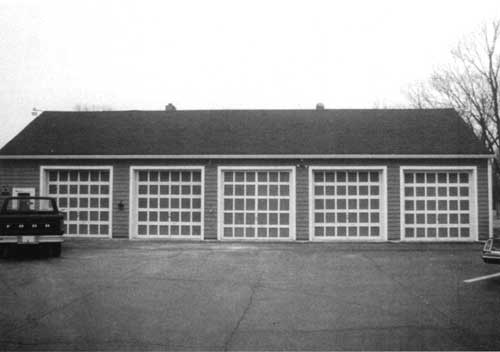

Figure 69: The old maintenance utility building. (NPS/February 1989) |

Figure 70: Modern maintenance building. (NPS/Rebecca Jones, spring 1996) |

Substantial remodeling and redesigning of the cramped visitor center began in the summer of 1994, resulting in its closure through November of that year. Addition of the long-awaited auditorium seating fifty people occurred as a component of visitor center redesign. Future development plans include further expansion or new construction of Hopewell Culture's principal visitor center. [53]

The maintenance utility building has perhaps seen the most change throughout the park's history. It, too, suffered from poor design, possessing an over-bearing, two-story height that dominated the park's landscape and dwarfed the adjacent residence. From its inception, both state and federal managers recognized the building's undesirability and recommended its replacement. Discussions in early 1949 held in the Region One Office determined that the building could be altered more economically than building a new fireproof structure. Richmond planners developed a new floor plan as well as a scheme to eliminate the second floor, its six dormer windows, and lower the roof. They planned to replace the hinged swinging doors, impractical for Ohio's snowy winters, with lift-type garage doors.

A decade passed before MISSION 66 development funds were available to implement the 1949 plans. By 1959, the Philadelphia Planning and Service Center exhibited "considerable hesitation" in undertaking the extensive rehabilitation, preferring the new construction route, but Regional Director Daniel J. Tobin overruled the office of design and construction. Clyde King concurred that the rehabilitation was more practical, the second floor space was not needed for storage, and that a lower roofline would help screen the building from the prehistoric Mound City Group. The work occurred during the summer of 1959. [54]

Few alterations to the maintenance building occurred during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1966, Maintenanceman Acton removed the inefficient coal-burning furnace for a contemporary model. In 1975, the building received a new roof. Both the utility maintenance building and the superintendent's residence were stained matching gray with white-painted trim to unify the complex. New gutters were also installed. [55]

To increase facility development and accommodate the expanded national historical park, construction of a new 3,200 square foot maintenance building came in 1994, providing three work and storage areas, a multipurpose room, and office space. NPS placed the long-awaited facility immediately to the east of the former maintenance and utility building, which workers began converting to operational use by resource management specialists in what became called the Resource Management Building. [56]

Since Clyde B. King's arrival on November 2, 1946, the residence served as required park quarters for the superintendent and his constant presence served to provide a degree of protection to the monument. A management inspection in 1961 recommended housing be provided to the park's archeologist. A similar inspection in 1962 noted the wisdom of including a second required housing proposal, but questioned its likelihood in light of the Kennedy administration's strict Bureau of the Budget and General Accounting Office fiscal views. [57]

Keeping a good coat of paint on the 1930s park buildings proved problematic. Paint applied to the redwood kept blistering and peeling, causing endless maintenance attention. The white buildings were frequently unsightly. Bill Birdsell's 1972 request for vinyl siding met with Philadelphia's rejection in favor of chemical stripping and repainting. In 1974, the contractor who performed the work damaged the existing aluminum doors and windows as well as the surrounding vegetation, and replaced the structural items at no charge. The extensive paint job also failed, yielding charcoal gray steel siding four years later. [58]

Birdsell's call for an air-conditioning system for the residence received sympathetic attention. The quarters suffered from humidity problems and became stifling during frequent air pollution blanketings by Chillicothe's paper manufacturing plant. Birdsell wrote, "We shudder to think of having to live through future summers here with mildewed furniture and clothing and to wake up at night because of the factory fumes. This, combined with the paint peeling off the walls and the house soggy with moisture, seems to us to justify proceeding with the installation." [59] Following the system's June 1973 installation, a grateful Bill Birdsell reported the humidity levels were finally under control, stating "This has made a big difference inside the house. The carpets are no longer buckled, the furniture is no longer 'sticky' and mildewing, the paint on the walls has stopped peeling, and even the basement is now dry and usable." [60]

In the late 1980s, NPS converted the residence into the park's administration building, foreshadowing radical changes to the physical plant with the creation of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. In anticipation of new construction, utilities work in 1993 at Mound City Group included natural gas pipeline installation to connect all buildings and replace the existing, inefficient heating and air-conditioning system. The same ground disturbance also accommodated telephone line installation to upgrade the outdated system. [61]

Renovation of the administrative headquarters followed in 1995, providing adequate space for copying and fax machines, a mailing center, central files, and a paging system. Work on the same structure in 1996 included remodeling the front entryway into a reception area and contracting to replace the building's windows and siding. The park library, shuffled from building to building and at one point suffering water damage, emerged from its boxed-up slumber in storage when volunteers organized it in the remodeled Administration Building. The new library room also featured work space for researchers and park staff. [62]

CONTINUE >>>