Administrative History

|

Hopewell Culture

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER SIX

Exhibiting the Hopewell Culture (continued)

| Exterior Exhibits |

Following construction of the visitor center museum building in 1960, it soon became apparent that visitors required interpretive signage in the outdoor areas of significant cultural and natural resource interest. The April 1963 installation of "The Mound City Necropolis" wayside exhibit immediately attracted visitor attention and appreciation. Placed just inside the entrance to the west wall of the mound enclosure, it helped orient visitors to the prehistoric topography surrounding them. [48]

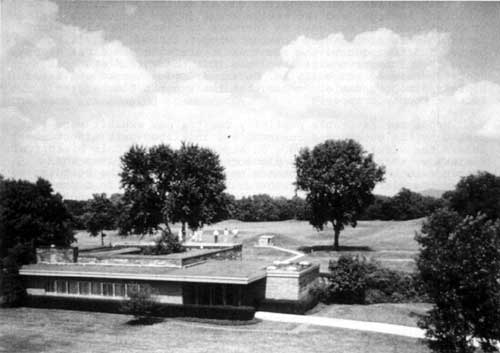

Figure 58: A button-activated audio program assisted visitor understanding while surveying Mound City Group on the visitor center observation deck. (NPS/Sprague Photography, ca. 1965) |

Figure 59: "The Mound City Necropolis" wayside exhibit. (NPS/Sprague Photography, ca. 1965) |

An interpretive audio program atop the observation deck during after-hours saw its first use in August 1965. In its first weeks of service, park employees noticed that its principal usage came in the early morning hours instead of in the late evening as anticipated. Upgrading audio messages to meet sound and quality standards came in 1973 through the efforts of Mound City Group Interpretive Specialist Robert F. Holmes working with the Harpers Ferry Center. [49]

A sign plan contained within an intepretive prospectus completed in the mid-1970s determined that the self-guided trail mapped out in the park's brochure was not adequate in interpreting key features to visitors. With the necropolis wayside moved outside the mound enclosure closer to the visitor center, the only other sign depicting the charnel house outdoor exhibit was temporary and did not meet standards. In 1976, six cast aluminum panels were developed: "Mound of the Pipes," "Death Mask Mound," "Scioto River," "Camp Sherman," "Charnal House Exhibit," and "Ohio & Erie Canal Stone." All six were installed in April 1977, and the mound area signs were placed close to the ground, abutting the slope of individual mounds. Others were mounted to metal stanchions. Maintenance workers mounted the panel on the Scioto River trail atop a stone pedestal specially constructed for the purpose in 1975.

The signs dramatically improved the self-guided visitor experience in the mound area as well as Scioto River trail. Fifty small metal photographic and text signs were installed throughout the area identifying native plants and relating how American Indians and white settlers used them in their daily lives.

According to the interpretive prospectus, intentions for the charnal house exhibit included full-scale reconstruction of such a prehistoric structure on either Mound 10 or Mound 15. However, National Park Service policy regarding any reconstruction changed in the 1970s in response to criticism that past efforts contained inaccuracies or were blatantly false. Official policy included rigorous criteria which had to be met prior to funding a reconstruction. Because archeologists could only speculate as to the above grade configuration of a charnal house, plans for the reconstruction were cancelled in 1976. Instead, the charnal house pattern post molds were highlighted on the ground. In turn, this became a maintenance dilemma attracting weeds and debris. In response, in 1985 a local Boy Scouts of America troop spread sand in the charnal house exhibit area as well as in front of other interpretive wayside signs. [50]

Figure 60: Charnel house exhibit. (NPS/ca. 1970s) |

Figure 61: "Pipe Mound" wayside exhibit. (NPS/ca. 1970s) |

By far the most visible exhibit within the Mound City Group enclosure was the mica grave at Mound 13. Begun in 1963 with Accelerated Public Works Program funding, the Ohio Historical Society designed and built the in-place exhibit as a component of its contractual partnership with the National Park Service to perform archeological excavations and restorations at Mound City Group National Monument. Archeologists chose Mound 13 for this intensive interpretive treatment because of the quality and quantity of its cultural resources. Its documentation by discoverer William C. Mills in 1920 proved to be another contributing factor in Mound 13's selection. The exhibit's purpose was to portray a group of Hopewell burials as they were discovered inside the prehistoric mound, including original cremated remains, four-by-six-inch mica sheets, replicas of copper head-dresses, and mica "mirrors" associated with two of the four burials.

Cy Webster of the Ohio Historical Society directed the mica grave construction, a concrete foundation with concrete block walls and a copper roof. The exhibit included a push button-activated audiotape recording, two ventilation fans, two florescent lights, and two floodlights. Construction work ended in October 1964, but because the exhibit window faced west, direct sunlight made the exhibit impossible to see. Substantial glare and reflection problems on the temporary glass panel necessitated a quick design change to incorporate a redwood baffle erected two feet in front of the exhibit. Accomplished the following month, the feature helped reduce the visibility problem and had the added attraction of identifying it for visitors by featuring "Mica Grave" in solid brass lettering accompanied by a Hopewell depiction of a falcon. Installation of permanent "Herculite" glass came on April 20, 1965, effectively completing the exhibit. [51]

Figure 62: Construction of the Mica Grave exhibit. (NPS/October 1964) |

Figure 63: The Mica Grave, directly behind the visitor center, attracted visitors inside the Mound City Group enclosure wall via a connecting concrete walkway. (NPS/early 1970s) |

Although the modern structure constituted an unmistakable intrusion on the prehistoric scene, its immediate popularity with visitors ameliorated those concerns. Despite its design flaws, the Ohio Historical Society expressed pride in the exhibit. On September 28, 1965, Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes visited Mound City Group National Monument with an entourage of twenty-five other dignitaries. His stop was one of several on a tour of historic, natural, and recreation areas in his "Wonderful World of Ohio" campaign designed to increase tourism. Superintendent James Coleman accompanied Governor Rhodes through the visitor center and then out to the mound enclosure with the first stop being the mica grave exhibit. Told that the Ohio Historical Society designed and built it, Governor Rhodes turned and told society director Daniel Porter that the exhibit "looks like a Jackson County crapper!" [52]

Hopes for favorable publicity for the new exhibit were dashed by the governor's remarks, and initiated park efforts to lessen the visual intrusion. On August 25, 1966, Ohio Historical Society workmen returned to place removable covers over the entrance to the exhibit, connecting the baffle to the building to reduce the glare problem further. Five days later in hopes of making it less intrusive, park maintenance painted the concrete blocks green. Coleman reported, "Everyone seems to agree that the appearance of the exhibit is much improved." [53]

In May 1979, severe deterioration in the form of leaking concrete walls and water accumulating within the mica grave exhibit threatened the burials and artifacts themselves. Within one week of reporting the emergency situation, the Midwest Regional Office provided funding and park maintenance workers removed the mound from around the building to expose its foundation and footings for cleaning, sealing, and installation of drain tiles. Taking advantage of the ground disturbance, park employees re-interred a partial skeleton previously donated to the monument. They subsequently restored Mound 13 to its correct configuration. [54]

Destruction of the redwood baffle in 1980 by vandals brought about its replacement with pine boards backed by plywood for added strength. By the late 1980s, the overall condition of the exhibit required rehabilitation to meet standards. Park maintenance treated the exterior in 1990, making it handicapped accessible, reduced glare, helped precipitation runoff, and replaced the sidewalk. In early 1991, Harpers Ferry Center via a contractor accomplished the interior exhibit rehabilitation. A freak lightning strike on May 18, 1991, damaged electrical outlets and melted wiring, but harmed nothing else. [55]

Until 1996, the mica grave was the most popular exterior exhibit at Mound City Group. With the previous removal of cremations, consultation with American Indians found the intrusive structure objectionable. NPS promptly removed all exhibit items and began planning alternative means of treating the mica grave using other media. [56]

CONTINUE >>>