Administrative History

|

Hopewell Culture

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER FIVE

Relations with the Community (continued)

| Veterans Administration |

One of the closest management relationships Mound City Group National Monument has actively cultivated for five decades is with the Veterans Administration (VA). The VA hospital inherited a large segment of Chillicothe's federal reservation following the World War I-era demise of Camp Sherman. As early as January 1947, Superintendent Clyde King reported the first fire caused by the VA's incinerator building: "The Veteran's Hospital has an incinerator at the northeast corner of this area, just over the boundary. When [the] wind is out of the north or northeast it is not unusual for entire newspapers to come out of the smokestack and ignite while sailing through the air. One of these started a fire which was extinguished before it got beyond the negligible stage." [1] VA administrators were amenable to relinquishing the incinerator and the surrounding 10.5-acre tract. Congressional approval of the land transfer came on April 3, 1952, along with an easement for the VA to continue using the incinerator and its access road until an alternative refuse disposal system became available. In the meantime, landscaping, reforestation, and restoration of a Hopewellian borrow pit by the National Park Service could commence on the new tract as funding permitted.

In the late 1950s as part of MISSION 66-related master planning efforts, Northeast Regional Office personnel focused their attention to solving issues related to Mound City Group, in concert with planned development. Assistant Regional Director George A. Palmer visited in June 1957 to meet with VA officials and discuss not only incinerator and road easements, but the VA's Baltimore and Ohio (B & O) railroad spur line and right-of-way that bisected the national monument itself. Discussions with Dr. H. H. Botts, VA hospital manager, revealed his frustration at not securing funding to move the incinerator building to another location. He welcomed National Park Service efforts at the Washington level to urge VA managers to fund the project. As for the railroad spur, Botts agreed that it should be relocated outside the national monument, but that the National Park Service would have to pay for it. The spur gave the VA a contracting advantage in bids for supplies traveling via rail, and especially for coal to fuel its central heating system. For annual maintenance, Botts estimated the spur required about four thousand dollars and carried 244 railcars. [2]

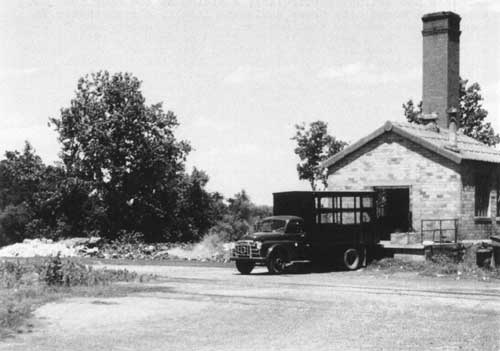

While an ultimate solution to the B & O Railroad spurline intrusion would have to wait, progress came swiftly on the incinerator. In 1959, the VA commenced its own landfill operation and stopped using its incinerator. In late September, the VA authorized NPS to close the paved access road from State Highway 104, and in January 1960, this same road along the original north boundary was obliterated. In July 1960, the VA declared the building surplus to its needs, and on August 24, authorized demolition. Clyde King lost no time in ridding his park of the eyesore. By the end of September, a contractor razed the building and restored the site to natural conditions. [3]

Figure 51: Veteran's Administration incinerator within Mound City Group National Monument's boundary. (NPS/1956) |

War Department funds paid for the 1920s construction of a spur from the B & O's mainline in Chillicothe north across the Federal Reformatory, Mound City Group National Monument, and terminating at the VA hospital. B & O operated the spur under a revocable permit. As National Park Service officials explained the need to have the intrusion removed in time for the visitor center's dedication, particularly a siding of the spur that cut across the Mound City Group enclosure itself, a sympathetic VA expressed its need to continue use. Superintendent John C. W. Riddle convened a meeting in his office on June 14, 1963, to discuss the issue with the VA, Federal Reformatory, Ohio Highway Department, and the B & O Railroad and laid the groundwork for eliminating the spur. In April 1965, two hundred feet of rails were detached from the siding of the B & O spur that bisected the mound enclosure. VA maintenance workers completed the cleanup of railroad ties the following month, filled in the cuts, and landscaped the grounds to the park's satisfaction. [4]

Final removal of the entire railroad spur through Mound City Group took another six years. In 1970, the VA began installing a gas-fired boiler to replace its coal-powered heating plant, thereby obviating use of the spur. VA hospital director Benjamin S. Wells requested that Superintendent George F. Schesventer put the National Park Service's request for the spur's removal in writing for the benefit of Wells' national managers. In his letter, Schesventer argued that a significant burial discovered under the tracks could not be removed. Because the railbed remained, funds could not be programmed to continue research and interpretive development. Finally, rising visitation increased chances for an accident and subsequent tort claims against both agencies as long as the hazard remained. [5]

Schesventer's effort succeeded. On June 16, 1970, Wells informed Schesventer that the VA would not require use of the B & O spur after September when the new boiler plant went on-line. Conditional to the line's removal was the VA's need to dispose of a crane and coal car already declared surplus. Problems with the conversion from coal to gas and surplusing the equipment caused a one-year delay. During the summer of 1971, the B & O spur permit was revoked, and the VA and National Park Service worked cooperatively to remove the tracks and railbed within their respective boundaries, and to revegetate the scar. Because the Chillicothe Correctional Institute required use of the spur from the B & O mainline, its part remained intact. [6]

(NPS/late 1960s) |

Monument staff became adept at steering away from park visitors those mentally unbalanced patients who occasionally wandered away from the VA hospital's neuro-psychiatric facility. Visitors reported one man in November 1962 wandering the mounds wearing a gun. Rangers found upon investigation the man wearing a toy pistol placed in a shoulder holster. In August 1968, a patient found his way to the maintenance utility building where he was given a soft drink and a cigarette, and to further mollify him, the superintendent's four-year-old son, Carl Schesventer, entertained him until VA orderlies arrived. Such patients were usually easy to identify because they were dressed in white clothing. Some met tragic deaths by attempting to swim the Scioto River. On February 19, 1984, one VA patient drowned on the monument's eastern boundary. On May 7 the same year, another patient was discovered floating downstream only semi-conscious. In 1989, yet another psychiatric patient cut his own throat while on park property, but his suicide was thwarted by VA police officers. [7]

Water and sewage treatment services for all government installations on Chillicothe's federal reservation were supplied by facilities at the Federal Reformatory. In the fall of 1966, this free service ended as the facility converted to a central water softener plant with metered service. National Park Service usage was set at 200,000 gallons per month and, based on total output, the charge came to $20 per month, plus a sewage treatment fee. The change came just prior to the state's conversion of the prison into the Chillicothe Correctional Institution (CCI) in December 1966. Managers negotiated a contractual agreement between CCI and Mound City Group National Monument during 1967. [8]

Securing an independent water supply became of prime importance in the early 1980s and prompted both agencies to find a common solution. Both the VA and national monument's water supply system was dependent on the Federal Reformatory and its successor, Ohio-owned and operated CCI. When the federal penitentiary transferred to the state, the VA agreed to find its own water supply, but continued to use CCI's sewage system. Increased water demands from the second prison built across State Highway 104 mandated not only the VA, but Mound City Group National Monument to look for new water sources. One option was to get water from the Ross County Water Company, but the utility lacked funds to build new lines to reach these potential customers. Preliminary park plans called for drilling a well at the maintenance area and establishing the monument's own system, complete with a small treatment plant. Another viable solution called for the two agencies to work together to solve the water dilemma. Because of the prohibitively high cost for obtaining water from the local utility company, VA engineers advocated drilling their own wells, using the existing VA water treatment plant, and permitting the national monument to tap into the VA system utilizing existing lines for a nominal fee. Ken Apschnikat recommended deferring a decision until VA planning progressed further. [9]

In the meantime, Apschnikat arranged to secure sewage and water for fire protection lines and irrigation purposes only from CCI. Agency managers agreed to maintain the $240 annual fee established in 1974 as a baseline sewage charge figure. In 1986, the monument installed a meter and shutoff valve on the CCI water line entering the maintenance shop. [10]

Test drilling for water on VA land proved unsuccessful. Hydrologists determined the aquifer from which CCI drew its water existed between the east side of State Highway 104 and the Scioto River, within the national monument. In April 1985, the VA began pressing the National Park Service for permission to drill test wells within park boundaries. Omaha officials determined that Superintendent Apschnikat possessed the authority to allow ingress to the VA, but urged the conditions be spelled out in advance, including following the advice of Midwest Archeological Center in Lincoln, Nebraska, in order to stay away from significant, subsurface cultural resources. Initially, Midwest Regional Office cultural resources specialists pressed the VA to conduct section 106 compliance review under the National Historic Preservation Act, and stipulated keeping drilling, well lines, and all construction activity within the abandoned railroad bed corridor. The land upon which the wells were to be drilled would be leased, not transferred, to the VA. Upon closer examination, Omaha officials quickly withdrew approval and asked Apschnikat to approach the VA with new concerns. [11]

In mid-June 1985, Apschnikat informed his counterpart that the tract in question, added to the national monument in 1982 because of a Hopewellian habitation site, possessed automatic National Register of Historic Places designation as a component of Mound City Group National Monument. The amount of ground disturbance required to drill a number of wells and to lay water and utility lines once potable water was found could have long-term impacts on significant archeological resources. Apschnikat urged the VA to exhaust all other alternatives, including adjacent state land, before considering National Park Service property. [12]

Three months later, VA officials were back with the same request. CCI refused to consider such a proposal, citing its own agricultural and facility expansion needs. The VA proposed moving the test drilling to the heavily disturbed gravel pit area in the monument's northeast corner where there were no known resources. Section 106 compliance, accomplished through the Midwest Regional Office, resulted in a "no effect" determination. A special use permit issued in January 1986, authorized VA drilling in the old gravel pit. By mid-February, drillers found a sufficient water supply and the VA requested an interagency agreement be negotiated to allow installation of production wells and water distribution systems. Negotiating the agreement took most of 1986 to achieve, with the National Park Service unwilling to grant an easement. Protection stipulations that would normally be written into an easement were incorporated into the final interagency agreement signed in November 1986. [13]

A primary component of the interagency agreement, for the VA to extend use of its facilities and certain privileges to National Park Service employees in exchange for obtaining one hundred thousand gallons of water per day, was estimated to save the small park's budget up to three thousand dollars annually. The 1986 agreement only formalized a practice that was already in place. In fact, the close association and special relationship dated to the days of Clyde King who found he could always rely on the VA to loan equipment or provide a critical service. In 1964, the VA began providing exams and licensing Mound City Group employees with government drivers' licenses when the first park assigned vehicle arrived. VA firemen and equipment responded to park fire alarms and drills, and staged cooperative fire prevention activities on monument grounds. In 1979, the VA's gymnasium became available to park employees two mornings each week. In 1983, permanent park employees were invited to join the VA's credit union. A year later, the monument issued a special use permit and joined the VA in staging what became an annual disaster drill on monument land. In 1986, the VA installed a special crystal on its radio system permitting expanded monitoring and radio communication with National Park Service law enforcement rangers, a service that became especially vital during emergencies and after park operating hours. [14]

Within the first year of the agreement, the monument received the loan of heavy equipment, locksmith services, road striping, welding services, hazardous tree removals, access to training programs, and VA employee association membership. In 1988, VA police joined park rangers in investigating an attempted burglary at the visitor center. The aforementioned services continued, but also included film processing, vehicle and equipment repair, metal shop services, and grounds and landscaping support. In 1989, the VA surveyed and produced drawings for a new sewer line, provided a dethatching unit for the lawn areas, took air samples to test for asbestos, and repaired the visitor center's door. In 1990, VA surveyors worked at the Hopeton unit to establish and re-establish park boundary markers. Coordination between the two agencies remains remarkably intimate. [15]

CONTINUE >>>