Administrative History

|

Hopewell Culture

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER FOUR

Administering the Mound City Group (continued)

| History of NPS Archeological Research |

Figure 42: Raymond S. Baby, curator of archeology, Ohio Historical Society. (NPS/Betty White, May 1974) |

National Park Service archeologists who compared the Squier and Davis survey with the restoration work performed by Mills and Shetrone in the early 1920s noticed that the extant configuration differed from the historic plan. An early 1960s report prepared by Northeast Regional Archeologist John L. Cotter made five recommendations to rectify the discrepancy. First, Cotter called for restoration of the borrow pits, one to the north of the rectangular enclosure, the other outside the northeast corner. Second, the earthen wall itself required restoration by finding the cross sections at each corner as well as on the north side. Third, Cotter wanted all mounds that lacked adequate excavation data to be base-tested to verify extant post molds because original mound circumferences were on or slightly within the post mold circles. These included mounds 1, 4-6, 10-11, 14-17, 19, and 21-24. Two small mounds outside the enclosure, north and south of the visitor center, also required verification. Fourth, other mounds needed to be checked for precise location and restored in height and shape per 1848 data. Fifth, Cotter called for the area to be tested again to corroborate 1848 and 1920s claims that no habitation evidence existed within or near Mound City Group.

Cotter recommended that NPS contract the work to the Ohio Historical Society's curator of archeology, Raymond S. Baby. He estimated that the excavation work would require two, six-month seasons, performed by about twenty laborers. Earthen restoration would cost $60,000, including $25,000 for investigation and research. As Cotter first conceived it, the contract would run from May 1963 to October 1964, with a final report due in 1965. [65] As work progressed, however, NPS ultimately expanded the project to span a dozen years.

Funding came almost immediately. The Kennedy administration's Accelerated Public Works Program made available $85,000 in January 1963, and the contract work began May 1. Contract supervisory archeologist James A. Brown from the Illinois State Museum served as Baby's onsite project manager, with Mound City Group Archeologist Richard D. Faust looking after NPS interests. In the first month, the team found the charnel house and a cremated burial of Mound 10 beneath Camp Sherman's Toledo Avenue. Below grade of the charnel house was a subfloor tomb, which in addition to the crematorium, were a copper headdress, adze, and beads, as well as shells and freshwater pearls. Workers subsequently picked up and moved the 1920s Mound 10 reconstruction to its proper location. During the second month, Superintendent Riddle reported his pleasure at increased local press coverage, stating the new finds "have changed a somewhat static [public] attitude" toward the park and spawned increased demand for an interpretive program. Indeed, locals were intrigued by the discovery of a previously undocumented borrow pit near the earthwall's exterior southeast corner that yielded the first skeletal Hopewellian burial ever found at Mound City Group. Placed with the skeleton were nine flint knives. [66]

Figure 43: Excavated Mound 10 revealed a post mold pattern of a structure as well as a ditch associated with a Camp Sherman street, visible as a dark linear stain. (NPS/ca. 1963) |

Figure 44: On the southwest corner periphery, archeologists discovered and restored a previously unrecorded borrow pit. (NPS/John C. W. Riddle, September 1963) |

Work performed in August 1963 ascertained that the entire south earth wall had been incorrectly sited during the 1920s restoration, including its opening leading towards the river. Archeologists did not remove a skeletal burial partially exposed outside the south earth wall because it rested beneath the railroad spur right of way. In September, reexcavation of Mound 13 occurred with the south enclosure wall accurately located thirty-five feet away. Archeologists ascertained Mound 13's true configuration, and restoration of the in situ exhibit, known as the "great mica grave," was deferred until 1964, its outline marked by wood posts protruding a few inches above the restored mound's surface. A "carbon 14" date performed on charcoal from the cremation burial found in Mound 10 produced an A.D. 178, plus or minus fifty-three years, result. The new test provided the "closest and best authenticated carbon 14 date for Mound City Group and one of the key dates for the entire Hopewellian culture." Regional Archeologist Cotter further reported at the conclusion of the first field season:

The work beneath Mound 13 has now revealed two complete charnel house floors, one rectangular and one square with double wall post molds. At the margin of the Mound, but associated with Hopewellian occupation, an extended burial has been found in good condition. The individual has an undeformed head, long in proportion to width, indicating a true Hopewellian physical type.... The outline of Mound 13 has been determined accurately to have been 70 feet rather than nearly 100 feet as reported by Squier and Davis, and its estimated height according to the 70 foot diameter would be 14 feet.

It is now beginning to be apparent that the original placement of the Mounds within the enclosure was symmetrical and with a well-defined pattern rather than the haphazard one apparent to the visitor in the faulty restoration of 1923. Present indications are that when the restoration is completed Mound City Group will take on a far more meaningful appearance and will interpret more accurately the true intention of its builders. [67]

Figure 45: Excavation and recording of Mound 13. (NPS/John C. W. Riddle, October 1963) |

Figure 46: Mound 13 post patterns and remnants of original floors indicated the presence of two structures, one built earlier than the other. (NPS/May 1963) |

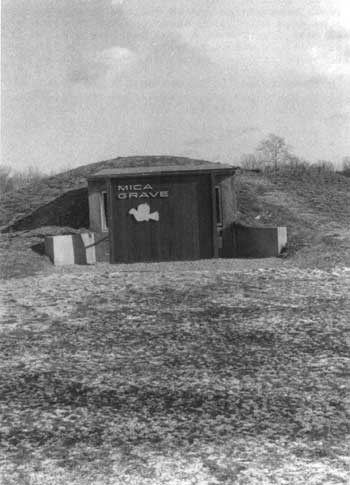

Figure 47: Construction of the Mica Grave Exhibit necessitated installation of a vertical panel to reduce glare on the glass. NPS removed this exhibit and restored Mound 13 in 1996. |

With a six-man crew employed by the Ohio Historical Society and Richard Faust as supervisory archeologist, the second phase of restoration work began on July 29, 1964. Work focused on restoration of Mounds 4 and 5. Excess earth taken from the construction of the great mica grave exhibit, also underway in 1964, went to Mound 4 in addition to a new load of dirt obtained to restore the mound to sixty feet in diameter by three-and-a-half-feet high. Contemporary disturbances at Mound 4 had all but obliterated it, save for post molds and its charnel house. [68]

Construction of the mica grave exhibit concrete structure continued through the winter of 1964-65, with the glass front installed in mid-1965 to reveal in situ ashes in four burial pits. Securing an additional $2,500, NPS extended the Ohio Historical Society's contract to perform additional location work on Mound 5, restore the northwest corner of the enclosure wall, and excavate Camp Sherman debris out of the borrow pit at the same corner. Work on this phase began on September 27, 1965, with new Park Archeologist Lee Hanson overseeing the project. Mound 5 proved to be fifty feet west of where the 1920s restoration placed it, and twelve times larger. The work for this phase ended in early November 1965. [69]

Two Ohio Historical Society reports on the excavation/ restoration work were accepted by NPS in 1966. [70] However, archeological work yet continued. Park Archeologist Hanson, using power equipment wielded by the maintenance crew, restored a borrow pit north of the enclosure wall. Jim Ryan of the Ohio Historical Society assisted in the June 20-22, 1966, work that saw the removal of a large cottonwood tree and fill removed from the pit and stored for use in future restoration activities.

In October 1966, Hanson completed the excavation and restoration of the east gateway in the enclosure wall, with the incorrect gateway filled back in with soil. During the 1920s restoration, a depression caused by a Camp Sherman waterline was mistaken for the opening, while the correct one was filled in. Hanson made two recommendations that he directed be accomplished prior to siting an interpretive trail through Mound City Group. First, one of four mounds along the northern tier should be taken down and its charnel house pattern exposed to enhance visitor understanding. Second, whereas Squier and Davis recorded twenty-three mounds at Mound City Group, and Mills and Shetrone restored twenty-four, the mound in dispute required testing to authenticate it. [71]

Figure 48: Charnel house of Mound 5 appears in center of post molds marked by newspaper. (NPS/Lee Hanson, October 1965) |

No archeological work transpired during 1967, but resumed in 1968 with the Ohio Historical Society's excavation and relocation of mounds 17 and 23. Directed by Barbara S. Saurborn, the archeologists quickly determined that Mound 23's exact location was just to the south of where its 1920's position had been. Mound 17 took longer to pinpoint, but it was relocated to the southeast and its configuration proved to be larger. Baby announced the significant discovery that the charnel houses of mounds 17, 3, and 23 were in direct alignment through the center of Mound City Group. [72]

Figure 49: Elmo Smalley, Sr., uses heavy equipment to remove Mound 17. (NPS/Nicholas Veloz, Jr., April 29, 1968) |

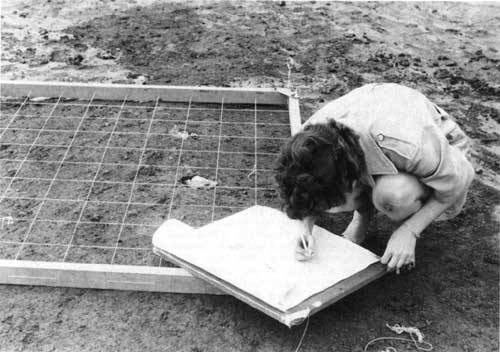

Figure 50: Ohio Historical Society's Martha Potter plots the post molds of Mound 17. (NPS/Nicholas Veloz, Jr., May 1968) |

With six of the twenty-four mounds verified, NPS wanted to extend the work to include the remaining eighteen mounds. A management appraisal report prepared in early March 1968, called for guidelines for the archeology program that "can be consistently followed by Northeast Regional Office and the changing superintendents and park archeologists." Acting Regional Director George A. Palmer informed Director Hartzog that the 1958 decision to retain Mound City Group was "based upon the premise that it would be an interpretive site. During the interim period it has been demonstrated that there were archeological deposits that had not been destroyed in the past and could be uncovered." Because the 1960's work proved successful in yielding new information, Palmer advocated "a thorough study and recommendation from the Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation" on the park's collection and research policies that constantly shifted with changes in park personnel. He observed the collection included an array of artifacts not directly associated with Mound City Group, gathered by off-duty personnel or donated by citizens. [73]

Ernest Allen Connally, chief of the office of archeology and historic preservation, directed NPS to continue its practice of cataloging artifacts excavated by the Ohio Historical Society, and advocated continued verification of mound locations. He acknowledged that artifacts the society previously excavated were unquestionably federal property, but "to make any real efforts to secure the collection at this time, when our relations... are excellent, would only have very unfortunate public relations repercussions." NPS facilities for curation and research at Mound City Group and Ocmulgee continued to be inferior to the society's. Connally recommended Park Archeologist Nicholas F. Veloz begin compiling an archeological research management plan to address outstanding issues. [74]

Another contract with the Ohio Historical Society in 1969 resulted in mounds 1 and 19 relocated to their original sites. Society employees involved in the effort were Baby, Assistant Curator Martha A. Potter, and Ohio State University students Wayne Haulpert and Steven Stathes, while Veloz and Edward Wolford represented NPS. Phase two, involving mounds 6, 20, and 24, came in 1970. [75]

A fortuitous discovery in 1970 yielded the location of Squier and Davis's field notes along with fifty pictorial plates. Long-standing efforts to locate the materials bore fruit when an astute researcher noticed in a 1954 reference book that the long-lost papers were in the Library of Congress. A request to the manuscript division yielded the response that not only did it possess numerous boxes of Ephraim G. Squier's papers, but it was in the process of microfilming all of it. [76]

Mound 24 testing conducted by Dr. Baby in 1970 revealed no subsurface features, thereby demonstrating that Mound 24 never existed. Mills and Shetrone mistakenly constructed it in 1923. Baby attributed the discrepancy to the Squier and Davis map that depicted twenty-three mounds, while the narrative stated there were twenty-four. In October 1970, workers removed Mound 24, and mounds 6 and 20 were moved slightly to the south to conform to their post hole patterns. In April 1971, excavation and relocation of Mound 12 began. It proved to be the most productive work in terms of artifacts since the investigations began in 1963, an unusual finding since the mound had previously been disturbed and excavated. Mound 12 also proved significant because of its charnel house pattern and single, not double, post holes. Experts speculated that the mound could represent one of the earliest constructed at Mound City Group.

Additional archeological work performed under contract by Ohio Historical Society in 1971 involved mounds 11 and 16, the last of the mounds north of the enclosure's center to be relocated to their true positions. Baby's work uncovered two nearly intact clay pots inserted into two postholes. Mound 11 had a charnel house with a single, not a double, doorway that opened to the east covered with a large canopy. It had nine interior roof supports, not the typical seven. Mound 11 proved to be twenty-five feet north of its original placement, while Mound 16 was only slightly off. Following up on the recommendation first made in 1966, the archeologists advocated Mound 15 not be reconstructed, but to have posts placed in postholes for visitors to see and better comprehend what lay beneath the mounds. [77]

Nineteen seventy-two saw the removal of the railroad spur through the mound group and restoration of the area. Removal of the ballast beneath the rails provided the opportunity to excavate the skeleton of an Indian woman initially uncovered in 1963 while probing for the southeast corner borrow pit. [78]

General Superintendent Birdsell found sufficient funds ($4,500) in the Ohio NPS Group's budget to accomplish research and restoration of Mounds 14, 21, 22, and the completion of interpretive exhibit Mound 15. Dr. Baby found the charnel house of Mound 15 to be rhomboidal-shaped with a north-south orientation directly aligned with Mound 3, which gave additional credence to his theory of mound alignment. Mound 15 proved to be 120 feet east of its 1920s predecessor. Treated wooden posts were installed to mark its post hole pattern, and a May 1974 dedication brought four hundred people to view the new exhibit. During the event, archeologists demonstrated their restoration and relocation methodology to quell persistent rumors that the mounds were being arbitrarily moved about. The same season saw Mound 14's restoration sixty-six feet southwest of its previous site, and among the scattered artifacts were pieces of sheet mica. Workers resited Mound 22 forty-four feet southeast of its previous location. This mound featured the second rectangular charnel house yet discovered. Orientation of the charnel house's long axis was to the west gateway of the earthwall enclosure. In the last project of the 1974 season, archeologists determined Mound 21 to be 180 feet off its correct site and filled with large pieces of Camp Sherman debris. [79]

Commiserate with the shift in NPS regional boundaries brought a move to assign project cost estimates based upon Denver Service Center (DSC)-devised figures. When DSC arbitrarily assigned restoration costs at $15,000 per mound, Birdsell exploded. Citing the Ohio Historical Society's niggardly $3,000 to $4,000 estimates, Birdsell complained to Midwest Archeological Center chief F. A. "Cal" Calabrese, "It greatly disturbs us to have an exorbitant and unsubstantiated amount programmed for each of these excavations when we have on record a lower relative firm estimate to accomplish this work." Birdsell feared that the high estimates would prevent Mound City Group from receiving programmed funds. The park would be forced continuously to siphon money from its own operating budget, supplemented by surplus Midwest Archeological Center monies, to keep its archeological program alive. [80]

Times had clearly changed as the professionalization of what became known as "cultural resources management" occurred in the 1970s. With the burgeoning field of public history thriving, thanks to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, universities and their allied partners in state historical societies and museums no longer dominated. That meant without traditional subsidization by academia by using students and volunteers, the true cost of such work emerged. With cultural resources management becoming standardized throughout the federal government, the cheap, good old days vanished. In archeology, this became acutely apparent. [81]

The 1975 season proved to be the capstone of the twelve-year archeological program. In the spring, an Ohio State University team of archeologists and anthropologists, led by Raymond Baby, excavated Mound 9 and relocated it ten feet north. In September, Baby's team investigated Mound 8, the site where Squier and Davis in 1846 uncovered nearly two hundred effigy stone pipes. Mounds 8 and 9 were in alignment east to west. Baby noted with the season's work, "major errors have been corrected" in restoring mound alignments at the park. He observed, a "deliberate orientation of the [charnel] house structures" with mounds 23, 17, 19, and 1 aligned 120 feet from one another. Carbon-dating analyses determined structures at Mound 10 at 179 A.D., the south earth wall at 61 A.D., and Mound 17 at 358 A.D. [82]

After 1975, there was only one additional mound excavation at Mound City Group. In early 1975, the Midwest Regional Office discovered activities in its Ohio parks were not in conformance with section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Section 106 guidelines, promulgated in the early 1970s, provided the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation an opportunity to comment on federal projects determined to affect National Register-eligible resources. With the passage of the 1966 legislation and the creation of the National Register of Historic Places, cultural units of the national park system, including Mound City Group National Monument, were automatically listed on the register. So as not to derail the 1975 season, Cal Calabrese pointed out to the Advisory Council that the work was being conducted by the Ohio state historic preservation officer's own agency, the Ohio Historical Society, and secured a verbal "no adverse effect" determination for work to be performed on mounds 8 and 9. [83]

The section 106 legal requirement coincided with a realization that final archeological reports produced by Ohio Historical Society contained scant administrative, interpretive, or scientific information beyond mound location and size of post molds. Issues of significance within the larger mound complex were not addressed. Upon Fagergren's recommendation, the Midwest Regional Office rejected Baby's report for mounds 14 and 22 until it contained adequate professional content per the purchase order agreement. Further, Fagergren called for Midwest Archeological Center's assistance in clarifying the park's management of its cultural resources, stating, "It is our belief further archeological investigations should not occur unless they can provide information useful to management and interpretation of the area. Past research has done little beyond verifying mounds locations and a greater cost-benefit ratio should be shown for justification of future work." NPS also pressed for Raymond Baby to submit long-overdue reports. Once received, a comprehensive synthesis of all past archeological work would yield research questions to fill remaining gaps in knowledge related to Mound City Group. Only then could responsible archeological excavations resume. [84]

David S. Brose of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History led a survey team in 1976 in areas identified for potential landscaping work to determine the presence of significant resources, and thereby eliminate those sensitive areas from consideration. The survey took place beyond the immediate mound group itself, and yielded conclusive evidence of Hopewellian activity. Brose noted,

A more significant result of these archaeological investigations is their demonstration of the presence of prehistoric Hopewellian activities beyond the walls, possibly associated with the ceremonial activities within the Mound City Group enclosure. Whether such occupation represents domestic or ritual behavior, and whether it is to be associated with some construction or post-construction phase of mound-building Hopewellian cultural behavior remains uncertain given the limited excavation and the extensive recent disturbance of the area. However, it is now clear that models of Hopewellian ritual, subsistence-settlement pattern, or regional exchange cannot justifiably use missing data as true negative evidence for occupation from the vicinity of the major Hopewell ceremonial centers. Hopefully, future archaeological investigations of Ohio Hopewell sites will concentrate less on the mounds for the dead than on the excavation of evidence for the living culture. [85]

Fagergren's discussions with Brose over books for the park's sales area led to a more grandiose scheme for the first professional conference devoted to Hopewell archeology. Held March 9-12, 1978, in Chillicothe, the conference received joint sponsorship by Mound City Group National Monument and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History with an objective of "providing adequate and current regional and topical data for discussion of the Hopewellian complex in Eastern North America." Proceedings of the conference did provide a sales item at the park. [86]

In 1977, the stone steps to the summit of Mound 7 were removed, thus eliminating visitor confusion concerning their origin and resulting in random use patterns within the mound group. Maintenance workers repaired the eroded scar and reseeded the following year. In 1979, excavation of Mound 9, in the program pipeline since 1975, took place and received its correct siting. Bruce Jones and Bob Nickel of Midwest Archeological Center first used a proton magnetometer at Mound City Group in August 1979 on areas to determine magnetic differences between Camp Sherman remains and less disturbed areas. [87]

Working with Martha Otto, curator of archeology at the Ohio Historical Society, Fagergren tracked down long-forgotten purchase orders and firmly pressed for completion of outstanding mound excavation reports. Reports for mounds 11, 12, and 16 were approved for payment in 1980, with the remaining reports on mounds 21 and 24, following soon after. [88]

In 1982, Regional Archeologist Mark Lynott, assisted by Sue Monk, Bob Nickel, and Chris Schoen, surveyed surplus Department of Justice land north of the park boundary designated for addition to the monument. Their survey demonstrated the area contained a significant Hopewell occupation site, most likely related to Mound City Group. Monk's work at the park with faunal remains indicated a disproportionate number of rib cage sections were brought into the mound enclosure, thereby bolstering the hypothesis of Mound City Group not ever having been permanently inhabited. [89]

The report and subsequent work has established that no one previous to A.D. 900 or 1000 in the Eastern United States were true agriculturalists. While the Hopewell may have used maize for gardening, they did not practice dedicated farming. Most Hopewellian peoples practiced a fully agricultural economy, but it focused on a suite of native annual seed-bearing plants. [90]

By the early 1980s, the National Park Service lacked basic data only on Mounds 3, 7, and 18. None of these had been re-excavated since the 1920s, nor had two other mounds to the west outside the earthwall enclosure. The latter mounds were suspected of being 1920s fabrications, approximately sited to mimic mounds which appeared on Squier and Davis' map. Modern archeological methods would certify the authenticity of these unrestored mounds. [91]

James Brown of Chicago's Northwestern University received custody of some of the Mound City Group archeological collections to produce a contracted synthesis of past research and excavation efforts. In response to Brown's concern regarding the condition of the collection, Mark Lynott and Melissa Connor, both of the Midwest Archeological Center, met with him to discuss the issue in November 1983. The archeologists noted mistreatment of the collection by "improperly trained personnel" resulting in "considerable damage to the research value of the collection." Lynott recognized curation and cataloging practices performed on the archeological collections "without insuring that basic provenance information about the artifacts is preserved." The consensus recommendation was either to add a professional archeologist to the park staff to manage the collections or to transfer the artifacts to Midwest Archeological Center to ensure proper care. [92] The curatorial concern remained until the transformation of the monument into a large, multiple unit national historical park. Following a two-decade absence, the park added a term-appointment archeologist to its staff in the mid 1990s.

The combined body of twentieth-century archeological reports related to Mound City Group excavations are of poor quality, lacking basic, detailed information, and in many cases, maps. Contemporary experts find reconstructing an informed history of Mound City Group archeology nearly impossible based upon the hastily-prepared reports, most of which were accomplished by the Ohio Historical Society. This observation applies to most other reports of the pre-1970 period, including those of the National Park Service. Future excavations will have to be based upon legitimate research questions in areas such as chronology and persistent cases of verifying mound placements. [Archeology related to Hopeton Earthworks appears in Chapter 10.] [93]

A minor footnote to the archeological history of Mound City Group is the National Park Service's role in the controversial work of Arlington Mallery related to the mysterious "iron furnaces" found in the western half of Ross County. Intrigued by his search for pre-Columbian stone masonry, Mallery visited Spruce Hill in 1948, discovered what he determined to be iron slag, and began formulating his theory of a pre-Columbian Iron Age in North America. Mallery began excavating more than a dozen archeo-pyrogenic sites, or iron furnaces, and as press coverage spread news of his findings, public curiosity grew. Mallery attempted to lend credence and prestige to his findings by declaring his iron materials would be displayed by the National Park Service at Mound City Group National Monument. Mallery did so in the absence of Superintendent King. Upon his return, King restricted the viewing to scientists and consigned the display area to the maintenance building, thereby limiting and controlling the publicity. In the Chillicothe area, the publicity proved largely negative.

Mallery and his display were at Mound City Group from November 23 to November 30, 1949. Other than a few scientists, no more than twenty-five individuals viewed the materials. Raymond Baby denounced Mallery's findings, stating "The evidence does not warrant any of the claims." Dr. S. L. Hoyt, metallurgist, declared it "interesting but not conclusive." [94] Ralph Solecki of the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology, in the area conducting river basin surveys along Deer Creek and Paint Creek for flood control along the Scioto, also visited. Solecki even inspected the Mallery sites themselves and denounced the Norse or Viking furnaces as "nothing more than lime-burning pits which probably date from the period of the construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal in about 1835." [95]

Undaunted, Mallery went on to publish his work in 1951 in a book titled Lost America, which gained even more popularity when a related article appeared in National Geographic Magazine. An updated version, co-authored by Mary Roberts Harrison in 1979, eleven years after Mallery's death, was titled The Rediscovery of Lost America. In assessing Mallery's work, David Orr criticized it as "sloppy even by contemporary standards" in that he demolished sites in his zeal for corroborating evidence. Further, Orr charged Mallery "stacked one questionable claim upon another until he could conclude exactly what he had hoped: that the pre-Columbian New World had been visited by a superior race of people--undoubtedly of European" origin. [96]

Although some individuals and organizations still herald Mallery's claims, no professional archeologists have been willing to examine extant evidence or search for more. References and inquiries to Mallery's work, however, still occupy Park Service attention and will continue to do so as long as the mystery of the iron furnaces persists. [97]

Following up on the successful 1978 Hopewellian conference, "A View from the Core" took place in Chillicothe on November 19 and 20, 1993. Co-sponsored by Hopewell Culture National Historical Park and the Ohio Archeological Council, more than 250 individuals attended and heard papers presented by noted archeologists and anthropologists. One session saw Park Ranger Robert Petersen discussing how interpreters convert raw archeological research into material for public education. Participants were also able to tour the new units of the national historical park. [98]

Archeologist Bret J. Ruby, who began working at Hopewell Culture on a term appointment in January 1995, soon reinvigorated the park's archeology and cultural resource management program. Giving the program increased visibility, Ruby initiated a monthly archeology column in the Chillicothe Gazette. Some 1995 accomplishments included hosting an Ohio State University-Midwest Archeological Center field school at Hopeton designed to salvage Hopewellian occupation sites. The public benefitted from weekly public lectures by noted scholars connected with the field school. Ruby helped facilitate surveys adjacent to Hopewell Mound Group to determine if the boundary adequately encompassed archeological resources. Conducted through the cooperative agreement with Ohio State University, Dr. William S. Dancey performed inventory and evaluation work that continued into 1996. Ruby led park personnel in similar activities at Spruce Hill Works, part of a special resource study mandated by Public Law 102-294 to determine the suitability and feasibility of adding it to the national historical park. With the assistance of outside researchers, Ruby directed geophysical surveys at High Bank and Hopeton.

To spearhead interest in the Hopewell culture, Midwest Archeological Center in the mid-1990s launched a newsletter entitled "Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio Valley." Designed to attract widespread professional attention in the field, the newsletter also effectively consolidated into a single format news of recent site preservation developments, research conducted, and published material pertaining to the Hopewell. [99]

In the summer of 1996, Archeologist Ruby undertook investigations at Hopeton Earthworks, utilizing staff and students from Milton Hershey School in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Assisting with the special field school were Forest Frost and Karen Archey of Midwest Archeological Center. This effort concentrated on excavating in the northwest corner of the large square earthwork. Using radiocarbon dating, three construction periods were noted, the earliest commencing circa A.D. 20. The crew also uncovered prairie soils beneath the earthworks giving additional clues as to natural conditions during the Hopewellian era. During the same season, NPS also surveyed sixty-five acres along the high terrace west of the earthworks and found assorted small sites of prehistoric and historic occupations. They employed remote sensing technology to find, using the Squier and Davis map, an almost undistinguishable circle and ditch enclosure near the southeast corner of the large Hopeton square. Throughout the field season, interpreters delighted in presenting public bus tours, evening programs, and special talks for the Archaeological Society of Ohio and other groups.

The 1996 archeological season yielded completed fieldwork at Spruce Hill Works for the congressionally-mandated special resource study. Results determined that "1) the site retains a high degree of overall integrity despite some localized areas of disturbance; 2) portions of the 'stone wall,' especially the gateways, are human-made and represent a monumental investment of human labor in construction; 3) Woodland period ceramics and Hopewellian stone tools were found in direct association with one of the gateway features, strongly supporting the conclusion that the site was built by Hopewellian peoples between ca. A.D. 1 and A.D. 400; and 4) several locations in reaching temperatures in excess of 1100 degrees Celsius. However, their cultural affiliation remains open to question." [100]

Evaluation of resources within and around 1992 designated boundaries is ongoing with adjustments expected at Hopewell Mound Group and Seip Earthworks.

CONTINUE >>>