|

FORT DAVIS National Historic Site |

|

These views show Fort Davis in 1875, by then a post tolerably

comfortable for the times and place. Above is the commanding officer's quarters.

The two officers in the foreground are 2d Lt. Charles G. Ayers, 10th Cavalry,

and 1st lt. H. B. Quimby, 25th Infantry. Standing in the left lattice opening is

2d Lt. James C. Ord, 25th Infantry, and in the right is 2d Lt. Henry H. Landon,

25th Infantry.

National Archives

Life at Fort Davis

LIFE AT FORT DAVIS DIFFERED little from life at other frontier posts of the time. Scouts, patrols, escort duty, and campaigns were part of the life throughout the period of Indian hostility. For most, these were welcome diversions, for the routine of garrison existence accounted for the greater share of one's service. Day after day, official activities followed the same monotonous pattern: mounted and dismounted drill, target practice, care of weapons and stock, fatigue labors, guard duty, inspections, parades, and a variety of other tasks.

Under the post commander, each officer and man had his part to play. The post adjutant and the sergeant major were the administrative voices of the commanding officer, with whom they shared offices at post headquarters on the north edge of the parade ground. Most of the commander's orders were transmitted through these men. The post quartermaster officer and sergeant were responsible for clothing, housing, and supplying the garrison, the post commissary officer and sergeant for feeding it. They occupied offices and warehouses south of the corrals during the 1870's, then moved to new buildings north of the corrals in the 1880's. The post surgeon, aided by the noncommissioned hospital steward, presided over the hospital behind officers' row and also looked after the sanitary condition of the fort. Each company was supposed to have a Captain and two lieutenants, but this was an ideal rarely achieved. Company officers could be found supervising their units in the field or occupied with paper work in the company orderly room in the barracks. Sergeants and corporals of the line usually stayed with the troops. Numerous enlisted specialists—blacksmith, farrier, saddler, wagoner, wheelwright—worked in shops that formed part of the quartermaster and cavalry corrals. At specified times of the day, an infantry bugler or cavalry trumpeter blew the appropriate calls that regulated the routine of the military community.

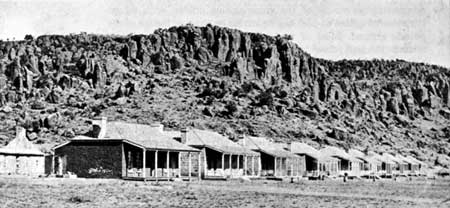

At top is officers' row, and to the left of it is the roofless ruin of

stone barracks, built in 1856. The bottom photo surveys the post from the southwest. In

front are barracks and behind are the quartermaster and cavalry corrals.

National

Archives

The troops ate their meals in buildings housing kitchen and messroom adjoining each set of barracks. Staple fare had changed little since the 1850's. In 1877 the meat ration consisted of three-tenths bacon and seven-tenths fresh beef. Beans and flour were purchased locally, and bread came daily from the post bakery. Scurvy swept the garrison in the spring of 1868, and the surgeon, Dr. Daniel Weisel, stressed the necessity of including plenty of fresh vegetables in the diet. In 1869 he persuaded Colonel Merritt to start a post garden. Two were planted, one of 4 acres on Limpia Creek for the post and one of 3 acres at the spring southeast of the corrals for the hospital. These gardens flourished year after year until abandonment of the fort in 1891. Some of the officers' wives kept chickens, but Major Bliss thought that they made the post look unmilitary, and he decreed that "On and after Feb. 1, 1874, no fowls will be kept within the limits of this garrison." Dr. Weisel thought it worth noting that, unlike white troops, Negro soldiers customarily ate their entire ration.

Water for all purposes was hauled from the Limpia in water wagons. The troops suffered from chronic dysentery, and everyone blamed the water. Dr. Weisel, however, insisted that it was pure and that "the water is made a shield of carelessness and neglect in enforcing necessary hygienic and sanitary measures." Nevertheless, in 1875 the spring was substituted for the Limpia as the source of water. By 1878 the drainage ditch leading to the spring had become "the resort of pigs" (chickens were probably back, too, now that Major Bliss had been transferred), and the water took on impurities. Finally, in 1883, construction began on a new water system, with a well and a steam pump on the Limpia and pipes leading into the post.

The state of sanitation was a constant worry to the post surgeon. Dr. Weisel complained that the squad rooms in the barracks were "very untidy, dirty and disorderly," that the kitchens and messrooms were equally dirty, that the sinks were "in a very bad condition," and that "offal and slops" were not hauled away as often as necessary. The doctor also tried to get orders issued requiring every soldier to bathe in Limpia Creek at least twice a week during the summer, but he appears not to have been successful. "The difficulties of a medical officer . . . at a frontier post," he wrote, "can only be fully estimated by actual and trying experience." And, he added, "much more might be said."

The regimental band provided entertainment as well as martial

inspiration at the frontier post. The 9th Cavalry band served at Fort Davis

in the 1870's. here it is shown in the plaza of Santa Fe, N. Mex., about 1885.

Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe

For diversion, the troops had a band, a library, a chapel, and a school, the last usually presided over by the chaplain. But the chief off-duty pastimes were gambling, drinking, and sampling the pleasures of the village of Chihuahua, just off the reservation. Boasting a population of about 150 Mexicans and 25 Americans, all dependent on the Army or the stage line for a living, Chihuahua was the scene of frequent violence. In October 1870, for example, someone shot Pvt. Anderson Merriweather with an army pistol. The bullet tore up his stomach, and Dr. Weisel could not save him. Several months later Pvt. John Williams got into a scrap with a comrade and was killed instantly with a butcher knife. Similar incidents occurred regularly. Diversions took their toll on officers, too.

On January 16, 1870, a captain died "of acute inflammation of the stomach produced by intemperance." Major Bliss tried to put a stop to some of this sort of trouble. In November 1873 he issued two general orders, one forbidding gambling on the post, the other forbidding enlisted men from "carrying concealed weapons of any description, especially knives, razors, slingshots and pistols."

There were also wholesome forms of amusement. Especially did the garrison look forward to the annual Fourth of July holiday. After the ceremonies commemorating American independence, the men played baseball and organized competition in foot racing and wheelbarrow racing. An accident marred the celebration of 1873. A soldier fired the salute gun before Pvt. John Jordon had withdrawn the rammer. Jordon received severe powder burns on the face and was speared in the arm by the broken rammer.

Many of the officers had their wives and families at the fort, and the women took an active lead in organizing social diversions. Balls, charades, dinner parties, and weddings were frequent and well-attended events. The arrival of official visitors from other posts or from department headquarters in San Antonio always prompted parties of one kind or another; and such occasions as the inspection of Fort Davis in 1882 by General of the Army William T. Sherman and staff were highlights of the continual war on monotony.

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Fri, Oct 18 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |