|

ANTIETAM National Military Site |

|

APPENDIX

The Emancipation Prodamation

On August 22, 1862, just one month before Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, he wrote a letter to Horace Greeley, abolitionist editor of the New York Tribune. The letter read in part:

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the National authority can be restored, the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was." If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time save Slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy Slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy Slavery. . . . I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty, and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free. . . .

For some months before the Battle of Antietam, as his letter to Greeley indicates, Lincoln had been wrestling with the problem of slavery and its connection with the war. He became convinced that a new spiritual and moral force—emancipation of the slaves—must be injected into the Union cause, else the travail of war might dampen the fighting spirit of the North. If this loss of vitality should come to pass, the paramount political objective of restoring the Union might never be attained.

Another compelling factor in Lincoln's thinking was the need to veer European opinion away from its sympathy for the South. A war to free the slaves would enlist the support of Europe in a way that a war for purely political objectives could not.

Thus, slowly and with much soul searching, Lincoln's official view of his duty came to correspond with his personal wish for human freedom. The outcome of these deliberations was the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Federal victory at Antietam gave Lincoln the opportunity to issue the proclamation—a dramatic step toward eliminating slavery in the United States.

By this act, Lincoln stretched the Constitution to the limit of its meaning. His interpretation of presidential war powers was revolutionary. It would become a precedent for other Presidents who would similarly find constitutional authority for emergency action in time of war.

More important, the proclamation was to inaugurate a revolution in human relationships. Although Congress had previously enacted laws concerning the slaves that went substantially as far as the Emancipation Proclamation, the laws had lacked the dramatic and symbolic import of Lincoln's words. Dating from the proclamation the war became a crusade and the vital force of abolition sentiment was captured for the Union cause, both at home and abroad—especially in England.

The immediate practical effects of the Emancipation Proclamation were negligible, applying as it did only to those areas "in rebellion" where it could not be enforced. But its message became a symbol and a goal which opened the way for universal emancipation in the future. Thus the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution are direct progeny of Lincoln's proclamation.

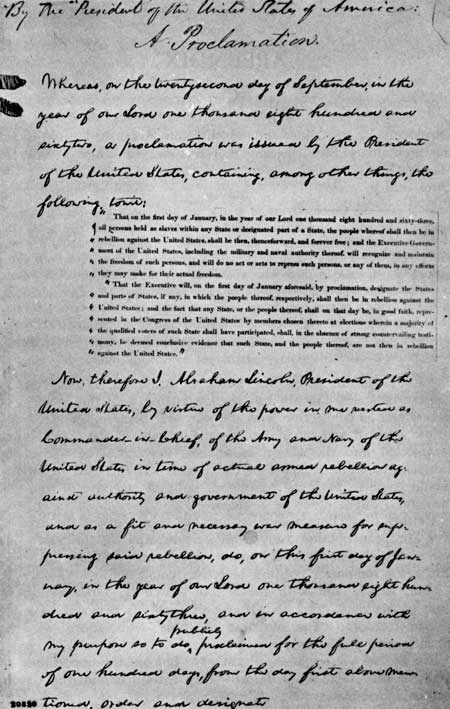

First page of Lincoln's handwritten draft of the formal

Emancipation Proclamation.

Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Any document with the long-term importance of the Emancipation Proclamation deserves to be read by those who experience its effects. Following is the text of the formal Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863:

BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A Proclamation.

WHEREAS on the 22d day of September, A.D. 1862, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and for ever free; and the executive government of the United Stares, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the executive will on the 1st day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State or the people thereof shall on that day be in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such States shall have participated shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State and the people thereof are not then in rebellion against the United States."

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, and in accordance with my purpose so to do, publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days from the first day above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof, respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the parishes of St. Bernard, Paquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkeley, Accomac, Northhampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Anne, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts are for the present left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States and parts of States are, and henceforward shall be, free; and that the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service,

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgement of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

|

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |