|

SCOTTS BLUFF National Monument |

|

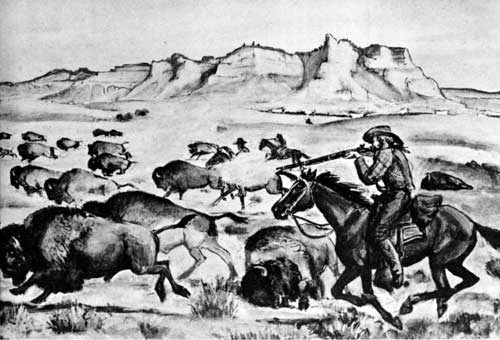

Hunting buffalo at Scotts Bluff.

Original

sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

Hunters, Miners, Cowboys, and Homesteaders

The ruthless hide-hunters were effective allies of the U. S. Army in ending resistance of the Plains Indian to the white man's advance. The American bison, or buffalo, had been the staff of life and the major source of food, clothing, and shelter for the Indians. Once vast buffalo herds, blackening the landscape, crossed and recrossed the North Platte River. The many expeditions and the emigrants on the California Road killed the huge shaggy beast wholesale. As a result, most of the herds withdrew to the southern Plains.

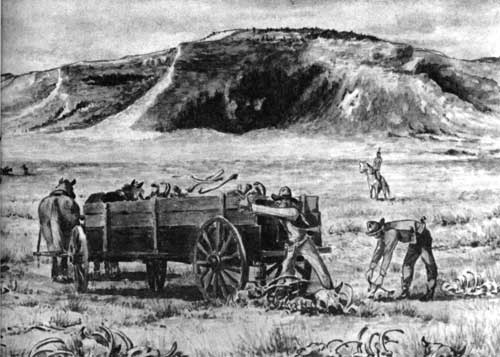

Loading buffalo bones at Scotts Bluff.

Original

sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

Construction of transcontinental railroads and the addition of new military posts along their route created a huge demand for fresh meat; in the East there was a good market for buffalo robes. The result was an intensive campaign of slaughter by professional hunters, armed with heavy Sharps and Ballard buffalo rifles. The stupid creatures were easy game for the hunter, who ran after them Indian fashion or calmly mowed them down from a prone position, as they grazed. In the mid-seventies the Kansas Pacific Railroad alone hauled out the carcasses of 3 million buffalo. It is estimated that more than 30 million buffalo were destroyed during the two decades, 1860-80. Descendants of the few creatures that survived this slaughter are now to be found only in zoos and in Government preserves, such as Yellowstone National Park.

The Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876 by-passed Scotts Bluff. Hopeful prospectors rode the Union Pacific Railroad to Sidney or Cheyenne, then followed trails northward to the diggings. The Sidney-Black Hills route crossed the North Platte over a private toll bridge at Camp Clarke, near modern Bridgeport. The Cheyenne-Deadwood Trail crossed a new Army-built iron truss bridge over the North Platte at Fort Laramie.

The last chapter in the pre-settlement history of Scotts Bluff could be entitled "The Cowboy Era." The open range cattle industry really began during Oregon Trail days, when sharp traders in the Fort Laramie area discovered that there was profit in exchanging one head of fat cattle for two that were worn out. They also discovered that oxen wintered well in the Laramie River Valley. Demand for cattle increased with the big Utah overland freighting business of the 1850's.

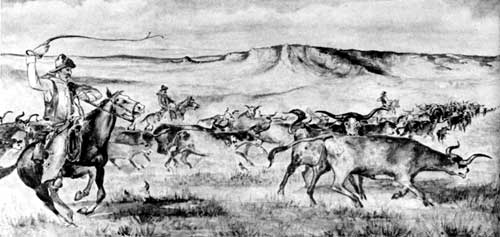

Cowboys driving longhorn cattle past Scotts Bluff.

Original sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

After the Civil War herds of half-wild longhorn Texas cattle were rounded up for the long drive northward to shipping points on the Kansas Pacific and Union Pacific Railways. In 1868 Texas cattle reached Kearney, North Platte, and Ogallala.

In the 1870's ranchers began to appropriate lush grazing lands in the North Platte Valley and its tributaries. It is said that by 1872 there were 60,000 head on Horse Creek, near Scotts Bluff. After the mop-up of hostile Sioux bands in 1876-77, thousands more were driven from Ogallala past Scotts Bluff toward the vast ranges in the northern Plains. Pratt and Ferris, Swan Land and Cattle Company, and the Coad Brothers were among the big outfits who grazed cattle in the Scotts Bluff area. Rapid inflation of the cattle market, overstocking and overgrazing, coupled with the disastrous hard winter of 1885-86, hastened the end of this short-lived but much publicized era.

In 1885 the first homesteaders, or grangers, arrived to stake out their claims in the Nebraska Panhandle. Gering was platted in 1888. In 1900 the Burlington Railroad was built up the north side of the Platte and the town of Scottsbluff was born. In 1910 a Union Pacific branch line was built up the south bank.

Where buffalo once roamed there are now irrigation ditches, sugar beet, alfalfa, and potato fields, and prime Herefords. The wily Sioux have become peaceful citizens. The dusty roads of the covered wagons have been replaced by broad paved highways and fast automobiles. Bullboats and Conestoga wagons have been replaced by long freight trains and cometlike aircraft. Scotts Bluff, named for one of General Ashley's fur traders, the brooding sentinel of the Oregon Trail, now belongs to history.

|

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |