|

KINGS MOUNTAIN National Military Park |

|

The Battle of Kings Mountain

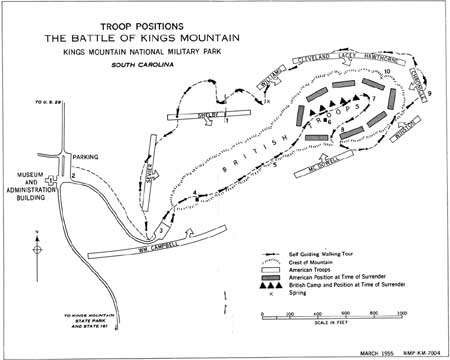

After passing through Hambright's Gap, the frontier detachments moved rapidly into their preassigned positions around the ridge. Seeking cover in the wooded ravines, the patriots advanced, and Campbell and McDowell hurriedly passed through the gap at the south-western end of the ridge. They took positions respectively on the southeastern and eastern slopes. Sevier formed along the western slope, while Shelby took position on the northwestern slope. Meanwhile, the other patriot detachments were forming along the bottom of the ravine leading around the northern and northeastern base of the ridge.

Ferguson's main camp was near the northeastern end of the ridge, but his picket line extended along the crest nearly to its southwestern end. About 3 p. m., as the patriots began to encircle the ridge, Ferguson's pickets sounded the alarm and engaged the advancing mountaineers in a brief skirmish. Then, as they reached their positions, Campbell and Shelby almost simultaneously opened the main attack. From the crest the Tories and Provincials replied with a burst of trained volley firing. But Campbell's and Shelby's men moved steadily up the slope Indian fashion, from tree to rock. For 10 to 15 minutes they maintained their attack, while the other patriot detachments moved into position around the ridge.

Troop Positions of The Battle of Kings Mountain.

(click in image for an enlargement in a new window)

While the trained Tory force "depended on their discipline, their manhood, and the bayonet," the mountain men relied upon their skill as marksmen. According to an eyewitness account of this phase of the battle "the mountain appeared volcanic; there flashed along its summit and around its base, and up its sides, one long sulphurous blaze." Ferguson believed steadfastly in the effectiveness of the bayonet charge, but the terrain at Kings Mountain proved "more assailable by the rifle than defensible with the bayonet."

As the two patriot commands neared Ferguson's lines, the Tories charged and drove them down the slope at the point of the bayonet. Though they had no bayonets, the patriots rallied at the foot, and the unerring markmanship of their deadly Kentucky rifles forced their pursuers to retire. Slowly following the retreating Tories and Provincials, Campbell's and Shelby's men were again driven down the rugged incline by the Tory bayonets. Taking cover behind trees and rocks, the two patriot commands again forced the Tories to retreat toward the crest.

Much of the volley firing of the Provincials and Tories, with their muskets and a possible scattering of Ferguson breech-loading rifles, was aimed too high. It passed harmlessly over the heads of the two patriot detachments, which now pushed even higher toward the crest. As the Tories began their third bayonet charge upon Campbell and Shelby, they were suddenly attacked along the northern and eastern slopes by the other patriot detachments. Moving to meet the patriot attack from these quarters, the Tories allowed Campbell and Shelby to gain and hold the southwestern summit.

Now completely surrounded, Ferguson's disorganized and rapidly decreasing force was gradually pushed toward its campsite on the northeastern end of the ridge. In this desperate situation, with attacks and counterattacks raging on all sides, the piercing note of Ferguson's silver whistle urging his forces on continued to be heard above the shooting and shrill whoops of the mountaineers. Suddenly, Ferguson attempted to cut through Cleveland's lines near the northeastern crest, but was struck from his horse by at least eight balls fired by the mountain sharpshooters. He died a few minutes later.

Capt. Abraham de Peyster, second in command to Ferguson at Kings Mountain. Courtesy New York Historical Society. |

Captain de Peyster assumed command and attempted to rally the confused surviving Tories and Provincials, but his efforts were useless and he ordered a surrender. During the bloody 1-hour engagement that raged along the heavily wooded and rocky slopes, the mountaineers gained a complete victory. They were veterans of countless frontier clashes, even though untrained in formal warfare and, with a slight loss of 28 killed and 62 wounded, had killed, wounded or captured Ferguson's entire force.

Order and quiet were not immediately restored to the rugged battlefield. A number of patriots continued to fire into the group of defenseless Tories, because it was not known that a surrender had begun. Others fired upon the Tories to avenge the merciless slaughter of Col. Abraham Buford's patriot force by Col. Banastre Tarleton's British raiders at the Waxhaws in South Carolina, on May 29, 1780.

While Dr. Uzal Johnson of Ferguson's corps tended the wounds of patriots and Tories alike, others buried Ferguson's body and those of the Tory dead on the battlefield. Of the patriots killed in the engagement, only four—Maj. William Chronicle, Capt. John Mattocks, William Rabb, and John Boyd—are buried there. They share a common grave at the site of the Chronicle markers.

"The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, 19 October

1781."

From a painting by John Trumbull. Courtesy Yale University' Art

Gallery.

The patriots rested on the battleground overnight. On Sunday morning, October 8, they started the homeward march. One week later they reached Bickerstaff's plantation near Gilbert Town with their prisoners. The frontiersmen had not dared delay their march, for they feared Cornwallis would send Colonel Tarleton in pursuit to avenge Ferguson's defeat. At Bickerstaff's, a court martial was held and 30 Tories were condemned to death; of these, 9 were hanged and the remainder spared. Since an investigation showed that these 9 Tories had robbed, pillaged, and committed more serious crimes, the patriots believed they were justified in this action. They also wished to retaliate for similar types of rude justice rendered so often in the past by the British.

The patriot detachments reached Quaker Meadows on October 15 with the prisoners. From this point they were marched northward toward Virginia; this was in accordance with the instructions of October 12 from General Gates, the American commander in the South. On October 26, Colonel Campbell entrusted Colonel Cleveland with the safekeeping of the prisoners and, with Colonel Shelby, called upon General Gates to determine the fate of the remaining Tories.

Meanwhile, the volunteer army melted away. Most of its members lost no time in returning to their home settlements. As the number of troops guarding the prisoners declined, escape became easy. After a long period of indecision, the remaining Tory prisoners were finally moved to Hilisboro, N. C., and exchanged. The mighty army of mountain men whose very existence confounded Ferguson, now vanished as quietly as it had gathered.

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |