|

VICKSBURG National Military Park |

|

This remarkable wartime photograph, taken by a

Confederate Secret Service agent, shows Grierson's cavalrymen near the

end of their 600-mile raid behind the Confederate lines.

From

Photographic History of the Civil War.

The Vicksburg

Campaign: Grant Moves Against Vicksburg— and

Succeeds (continued)

THE RIVER CROSSING. Grant's plan was to make an assault landing at Grand Gulf, a fortified road junction on the bluffs at the mouth of the Big Black River. On April 29, the Union gunboats pounded the Grand Gulf fortifications for 6 hours, seeking to neutralize the defenses and clear the landing for 10,000 Federal infantry aboard transports just beyond range of the Confederate cannon. The naval attack failed to reduce the Confederate works, and that night Grant marched southward along the Louisiana shore to a landing opposite Bruinsburg. There he was met by the fleet which then slipped downstream under cover of darkness. By noon of the following day, April 30, Grant was across the Mississippi, experiencing

a degree of relief scarcely ever equaled since. . . . I was now in the enemy's country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships, and exposures, from the month of December previous to this time, that had been made and endured, were for the accomplishment of this one object.

Grant's landing was unopposed, partly because of two diversionary movements and partly because of Pemberton's decision to hold his army close to Vicksburg and fight a defensive campaign. Both diversions were completely successful. On April 17, the day after Porter's running of the batteries had indicated Grant's strategy of striking from the south, Col. B. H. Grierson with 1,000 cavalrymen moved out from southwestern Tennessee on one of the celebrated cavalry raids of the war. They rode entirely through the State of Mississippi behind Pemberton's army to a junction with Union forces at Baton Rouge, La. In 16 days Grierson covered 600 miles, interfering with Confederate telegraph and railroad communications and forcing Pemberton to detach a division of infantry to protect his supply and communication lines. Sherman, whose corps had not yet made the march from Milliken's Bend, made an elaborate feint above Vicksburg. Loading his men aboard every available gunboat, transport, and tug, he landed at Haynes' Bluff, north of Vicksburg, leading Pemberton to expect the real attack from that direction. Both moves helped screen Grant's true objective.

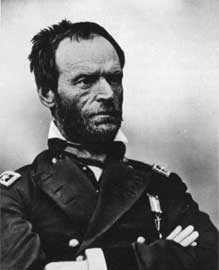

Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, commanding the Union XV Corps. Courtesy National Archives. |

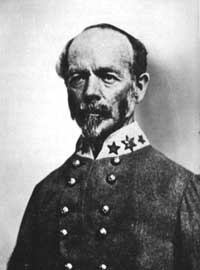

Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, commanding Confederate military operations in the West. Courtesy National Archives. |

The events immediately following Grant's landing revealed a basic difference in tactical concepts between Pemberton, commanding the Army of Vicksburg, and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, his superior, who was in charge of Confederate operations in the West. Johnston believed that to defeat Grant it would be necessary for Pemberton to unite his whole force in order to smash the Union Army, preferably before Grant could consolidate his position on the east bank. Accordingly, he wired Pemberton on May 2 "If Grant's army crosses, unite all your troops to beat him; success will give you back what was abandoned to win it."

It was Pemberton's concept that holding Vicksburg was vital to the Confederacy and that he must primarily protect the city and its approaches. To have marched his army to meet Grant "would have stripped Vicksburg and its essential flank defenses of their garrisons, and the city itself might have fallen an easy prey into the eager hands of the enemy." This inability of Pemberton and Johnston to reach agreement upon the tactics that might thwart Grant's invasion seriously affected subsequent Confederate operations and prevented effective cooperation between the two commanders in the Vicksburg campaign.

THE BATTLE OF PORT GIBSON. McClernand's Corps, immediately upon debarking on April 30, headed for the bluffs 3 miles inland. By night fall the Federal soldiers had reached the high ground and pushed on toward Port Gibson, 30 miles south of Vicksburg. From this point, roads led to Grand Gulf, Vicksburg, and Jackson. Maj. Gen. John S. Bowen moved his Grand Gulf command toward Port Gibson to intercept the threat, and, at daylight on May 1, leading elements of the Union advance clashed with Bowen's troops, barring the two roads which led to Port Gibson.

The battle of Port Gibson was a series of furious day-long engagements over thickly wooded ridges cut by deep, precipitous gullies and covered with dense undergrowth. While greatly outnumbering Bowen, McClernand was prevented by the rugged terrain from bringing his whole force into action. Slowly forced backward, Bowen conducted an orderly retreat through the town, which he evacuated. The holding action had cost Bowen 800 casualties from his command of 8,000; Union losses were about the same from a force at hand of about 23,000. Pemberton determined not to contest Grand Gulf lest he risk being cut off from Vicksburg and withdrew across the Big Black River. Thus he permitted Grant to occupy Grand Gulf and gave him a strong foothold on the east bank of the Mississippi.

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |