|

GRAND PORTAGE

A Report on Archeological Investigations Within the Grand Portage Depot (21CK6), Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota: The Kitchen Drainage Project |

|

INTRODUCTION

Grand Portage National Monument, located approximately 5 mi (8 km) from the Canadian border in extreme northeastern Minnesota, consists of three distinct elements: the Lake Superior Depot area, the site of Fort Charlotte on the Pigeon River, and the 8.5-mile (13.6-km) portage that connects them. The primary developed area of the Monument, however, is the reconstructed Depot. Today, the Depot contains two reconstructed fur trade buildings, the Great Hall and the Kitchen, which are open to the public seasonally (Figure 1). The interpretive mission of Grand Portage National Monument emphasizes events and personages associated with the fur trade in this region during the years 1731-1802.

|

| Figure 1. The reconstructed Grand Portage Depot as it looked during the 1989 drain installation. |

Since the time those two Depot buildings were reconstructed on their original sites, it has been known that ground water presented a threat to their structural integrity. Over the years, various attempts have been made to mitigate the water problems with only moderate success. Sump pumps beneath both structures served to remove some of the water, but certain problems persisted. This is especially true of the Kitchen structure, which has witnessed warping of its foundation and frost-heaving of its concrete crawlspace floor.

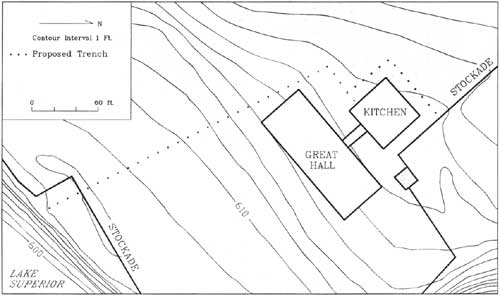

Because of those continuing problems, planners designed a drainage system that they hoped would improve drainage about the Kitchen and convey excess water to the lake (Figure 2). The proposed system entailed installation of an interceptor drain on two sides of the kitchen. Perforated pipe bedded in gravels, which in turn would be encapsulated in a filter fabric, would be buried on the north and west sides of the structure. That line would continue past the Great Hall toward Lake Superior, effectively intercepting ground water near that structure, as well. Downslope from the Great Hall, however, the pipeline would be solid. Furthermore, in order to limit the amount of new ground disturbance, that segment of the alignment was to follow an existing drainage line that was installed in 1975 as part of a sump pump system. It also was believed that an earlier drain (circa 1940) had run through this general area soon after initial reconstruction of the Great Hall.

|

| Figure 2. Plan of the proposed drainage system at Grand Portage. |

In addition to the interceptor drain, the new drainage system was designed to connect with existing sump pumps beneath the two reconstructed buildings. Short leaders of solid pipe would convey collected water from beneath the buildings to the installed line and thence to the lakeshore outlet. Thus, any water that might not be intercepted by the drain field could still be removed from the buildings by pumping it out.

Locational design for the drainage system reflects a conscious effort to place the necessary trenches in areas that were already known to be disturbed. The downslope conduit, for example, was to correspond to an existing drainage line while the interceptor drains north and west of the Kitchen fell within the zone excavated prior to its reconstruction. It was not possible, however, to determine a path that would totally avoid areas that might contain previously unknown cultural resources. In fact, there was some possibility that the drainage line might pass through the remains of a fur trade era structure investigated by archeologists in 1936.

For those reasons, a team of archeologists directed by the author traveled to Grand Portage National Monument for a two-week field project at the end of September, 1989. The Midwest Archeological Center (MWAC) crew excavated a total of seven test units in areas through which the drainage alignment would pass. Four of those units sought to determine whether any remains of the known fur trade structure still survived in the path of the drain. The others were intended to examine areas that were unknown archeologically.

Subsequent to the preconstruction investigations, local and regional National Park Service personnel were concerned that excavation of the drainage trench might still cause damage to resources that were undetected by the testing phase. Accordingly, the author was dispatched again to Grand Portage when the drain was installed in mid-October. All excavations for the drain, whether performed with heavy equipment or hand tools, were observed with an understanding that work would be halted temporarily if any intact archeological resources were noted in the process. The backfilling operation also was monitored in case a section of trench wall might collapse and possibly expose something of significance.

This report summarizes the methods and findings of all investigations carried out in conjunction with the drainage development. Background concerning previous archeological work within the Depot is provided, but more general information concerning the cultural and natural history of Grand Portage has been omitted from these pages. Adequate summaries of those topics already are available in other reports (e.g., Noble 1989; Woolworth and Woolworth 1982), eliminating the need to duplicate efforts.

The 1989 field investigations at Grand Portage resulted in the collection of artifacts representing virtually the entire human history of this region, from prehistoric times to the present. The potential of those objects to yield any significant archeological information, however, is diminished by the very high degree of disturbance at test unit locations. Since materials from various periods are mixed together in the same depositional contexts, it is obvious that they are redeposited and are not in an undisturbed state.

In view of the limited interpretive value of the artifact assemblage generated in 1989, the specimens will not be discussed as part of this report. The artifacts are inventoried in gross tabular format, however, in Appendix A. All materials and attendant field records are now curated at the Midwest Archeological Center facility in Lincoln, Nebraska, under MWAC Accession Number 335.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

noble-90/intro.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jul-2009