|

Animal Life in the Yosemite

|

|

|

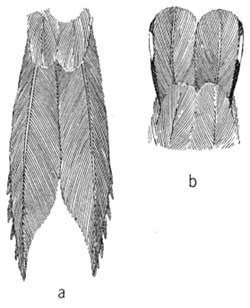

THE BIRDS SIERRA CREEPER. Certhia familiaris zelotes Osgood Field characters.—Less than half size of Junco; tail as long as body, each feather stiffened, and pointed at tip (fig. 58a); bill slender and curved. Coloration above dark brown streaked with white; under surface of body plain white. (See pl. 10h). Hitches jerkily, upward, on trunks of trees. Voice: Fine and wiry; song of male see', see', se-teetle-te, see'; call note, see, often somewhat prolonged, uttered at irregular intervals. Occurrence.—Common on west slope of Sierra Nevada. Permanently resident in Transition Zone, where recorded from Smith Creek (six miles east of Coulterville) eastward to floor of Yosemite Valley. Present in Canadian Zone at least during summer season when noted from Chinquapin to Porcupine Flat and Merced Lake. Wanders to higher altitudes (as on Dana Fork, 9500 feet) and to east slope of mountains (Walker Lake and Williams Butte) during fall. Winters in small numbers in western foothills, as near Lagrange. Forages on trunks and larger branches of good-sized trees, and nests in crevices behind loose bark. Solitary or in pairs. The Sierra Creeper is one of the least conspicuous of the common birds found in the Yosemite region. This is not due to any special reclusiveness on the part of the bird, for it often forages in situations quite open to view. Its effacement is due to its special scheme of coloration together with its peculiar manner of movement. Even experienced observers are sometimes put to considerable effort in locating and following one of the birds. The brown back with its narrow streaking of light color harmonizes closely with the warm tones and up-and-down pattern of the bark. (See pl. 10h). Only in side view, when the white under surface shows, and then especially if the bark be wet and so darkened, is the creeper likely to be seen easily.

The Sierra Creeper keeps closely to one restricted sort of environment, namely, the trunks and larger branches of trees. In our experience we do not recall a single exception to this rule. True enough, one of these birds was seen scaling up the slabs of cedar bark covering the exterior of the Camp Curry dining room, but even there the bird was obviously in its proper niche. The creeper's whole scheme of existence, its manner of foraging and of nesting, is more limited and specialized than is that of almost any other bird in the region. When on the trunk of a tree the creeper's progress is always upward. Sometimes it moves sidewise a short distance, though always with steeply diagonal a posture; often it spirals around the bole while ascending, and occasionally the bird will drop down a step or two; but it never runs down the tree or even turns head downward, as do the nuthatches. After ascending to near the top of one tree the creeper flies down to near the base of the same or a neighboring tree and there starts a fresh ascent. It moves spasmodically, hopping or 'hitching' upward a few steps, then stopping to make inspection when it sees anything of possible service such as food. The tail with its stiffened and pointed feathers is used habitually to give the bird support (fig. 58a). The bird turns its head this way and that, peering into crannies in the bark, and by means of the slender curved bill, used as tweezers, readily picks out insects from the deeper crevices. The creeper seems never to be at rest. Whatever the time of the day, it is on the move. The query arises: Do these birds need to forage incessantly, do they have to keep continually active in order to get sufficient nourishment? Or is part of their activity a matter of habit or an expenditure of excess energy really unnecessary? Whatever the answer, the fact is that the creeper, like many other small insectivorous species, whenever seen is always on the go. If the bird watcher in the field had to depend upon eyesight alone, the Sierra Creeper would be one of the 'rarest' birds in our forests. Fully half of our own notebook records have resulted from locating the bird first by hearing. The fine and 'wiry' note which it uses as both call and alarm note, see, or zeetle, is given practically throughout the year. In the spring season, there is added the song of the male, a series of notes of the same general character as the call, and of the same high pitch, see', see', se-teetle-te, see'. The voice of the creeper, especially its call note, is sometimes confused with that of the Golden-crowned Kinglet, and indeed the two are much alike although to the experienced ear there are points of difference. A beginning student should follow up individual birds of the two species and listen to their notes until he learns to distinguish them. It is not unlikely that certain notes of the creeper are so high as to be above the limit of hearing for some persons; this is known to be the case for the Golden-crowned Kinglet. The nesting activities of the Sierra Creeper are carried on in exactly the same surroundings that afford the bird its food and shelter at all times of the year. The space left where a slab of bark has split away from the trunk a short distance, affording a deep but narrow opening, is the place most often chosen to harbor the nest. Such sites are more common near the bases of trees where the bark is thicker and older and the outer portions often more furrowed and split. It is not surprising, therefore, that creeper nests are often within a very few feet of the ground. Once the site has been selected, both members of the pair busy themselves in bringing the materials needed for the nest. The form of the structure varies with the nature of the crevice which has been chosen, but in all cases the general plan is the same. The lower part of the crevice is filled with various kinds of coarse material such as sticks, old flakes of bark, moss, and rotted wood, until firm enough to support the superstructure. On top of this there is made a shallow cup, longer than wide, somewhat the shape of a narrow gravy dish. This part is composed of soft substances, most often weathered shreds of the inner bark of the willow. Creepers make direct approach when visiting their nests; the birds practice no subterfuges for keeping secret their location. Hence it is not difficult to follow a bird directly to its home. This was well illustrated by some observations of ours on a pair of creepers in Yosemite Valley on May 22, 1919. The birds had chosen a location about 12 feet above the ground in a large (30-inch) yellow pine. Entrance to the nest site was gained in this instance through a hole about an inch in diameter in one of the large slabs of bark. Both male and female were at work gathering moss from the trunks of black oak trees in the vicinity and carrying this material directly to the nest. When one of the birds entered the nesting cavity it would stay but an instant, and so it seemed that little attention was being given to the arrangement of the material at this, probably early, stage of construction. A nest was seen in the Valley on May 31, 1911, in a crevice at the tip of a burn on an incense cedar trunk. This was 14 feet above the ground and scarcely 20 feet from the busy office of one of the large camps. Evidence pointed to the presence of young. If young were there, the beginning of nesting must have been close to the first of May. A nest of the Sierra Creeper which could be studied in detail was found at about 4500 feet altitude near Indian Creek, below Chinquapin, on June 11, 1915. It was in a fire-scarred incense cedar, which had a large plate of bark sprung outward from the base of the tree. Behind this plate, at a height of 7-1/2 feet from the ground, the nest was hidden. The space between the bark slab and the body of the tree for a distance of 21 inches below the eggs had been filled with loosely laid flakes of cedar bark, and a few stray ends of these pieces of bark, projecting beyond the edge of the crevice, had given the observer who had noticed one of the birds his first clue to the exact location of the nest. The nest proper was a mass of felted inner bark of willow, silvery gray in color, longer than wide, about 4 by 2 inches, and was put together in more substantial manner than the underpinning. There were 6 eggs in which incubation had just begun. When the nest was first discovered the female was covering the eggs, while her mate was gathering insects on a tree 30 feet away. As the projecting slab of bark was lifted to gain better view of the nest, the sitting creeper left and joined her mate. Then, while examination of the nest continued, the two birds came down to as close as 8 feet from the observer and voiced their wiry protests almost continually. As will have been inferred, the Sierra Creeper is an exceedingly local bird, in that, having once selected a favorable neighborhood, it carries on all of its activities within a very short radius. Indeed, at nesting time, once an adult bird is seen, the observer may be confident of finding its mate and its nest close by. The materials for the nest, and the food for both parents and young, are gathered within a remarkably small circle. |

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

Animal Life in the Yosemite ©1924, University of California Press Museum of Vertebrate Zoology grinnell/birds184.htm — 19-Jan-2006 | ||