|

The Geologic History of the Diamond Lake Area

|

|

GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF THE DIAMOND LAKE AREA (continued)

THE ERUPTION OF MT. MAZAMA

From the close of the Pleistocene, some 10,000 years ago, to the present, the geologic history of the Diamond Lake area has been dominated by Mt. Mazama. Mt. Mazama is the name given to the vanished mountain peak whose collapse created the caldera now occupied by Crater Lake some 15 miles to the south of Diamond Lake. The major growth of Mt. Mazama was accomplished during the Pleistocene; and the volcano remained active until a few thousand years ago. After the ice receded, Mt. Mazama's smoking summit stood an estimated 12,000 to 14,000 feet above sea level.

A few thousand years ago Mt. Mazama began to erupt volcanic ash and pumice. At first the eruptions were weak and irregularly spaced, but they gradually increased in intensity and frequency. For a period of several weeks these eruptions continued. Pumice fragments ranging in size from fine dust to several inches in diameter were hurled from the vent. At the time of these eruptions the prevailing wind was toward the northeast. The pumice was light enough to be blown in that direction. The coarser fragments fell on the slopes of the volcano while the finer material was carried farther by the winds. In the Diamond Lake area the pumice fragments are mostly between 1 and 4 inches in diameter. Farther to the northeast, the material becomes progessively finer.

As the pumice fragments become smaller away from their source the thickness of the deposit diminishes. The thickness of the pumice blanket has been mapped by the use of isopach lines, which are lines representing equal thickness of the deposit. At every point beneath the 5-foot isopach, for example, the pumice is 5 feet thick.

After the pumice eruptions, which probably lasted for several weeks, the landscape around Mt. Mazama must have presented a grim appearance. The pumice covered the land like a blanket of dirty snow. Heat from the frothy glass killed the vegetation for miles around Mt. Mazama and produced a desolate wasteland.

|

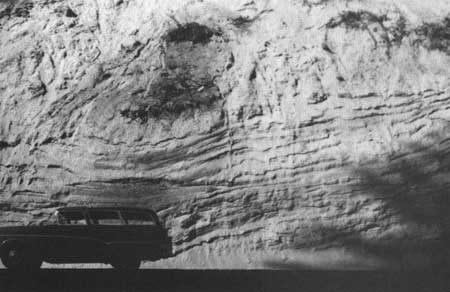

| Road cut in washed pumice deposit. |

The pumice accumulated to a depth of 5 feet in the immediate vicinity of Diamond Lake, Cinnamon Butte, Kelsay Point, and Windigo Pass. To the north and west the deposit becomes progressively thinner, and has a thickness of only 6 inches in the Fish Creek Desert and Toketee Falls areas. The 6-inch isopach line extends northeast to the vicinity of Bend, Oregon, some 70 miles from Mt. Mazama.

When the eruptions of pumice ceased, Mt. Mazama was silent for a period. Later, a few spurts of steam and pumice spouting from the vent signaled renewed activity. The eruptions rapidly increased in intensity; then came a series of stupendous explosions that must have been audible for hundreds of miles. A foamy mass of incandescent pumice and hot gas bubbled over the lip of the crater. Unable to overcome the force of gravity as had the earlier, less voluminous eruptions of pumice, the foamy mass rushed down into the valleys surrounding the volcano, with velocities approaching 100 miles per hour. This rushing cloud of frothy, glowing, pumice fragments and rapidly expanding gases—a glowing avalanche—enveloped the countryside.

The high content of hot gas gave the glowing avalanche extreme mobility. A portion of the gas and pumice that boiled over the lip of the volcano rushed down the Rogue River valley a distance of 35 miles; some flowed to the northeast as far as Chemult, 25 miles distant; and part of it flowed across the low saddle to the north of Mt. Mazama and rushed on toward Diamond Lake. The topography to the north of the saddle channeled the avalanche toward the south end of Diamond Lake. Somehow, the glowing avalanche passed over the surface of Diamond Lake, was funneled through the gap at the northwest corner of the lake, and continued down Lake Creek. Wells dug near the summer homes on the west side of Diamond Lake reveal the glowing-avalanche deposits in that area are between 25 and 30 feet thick. The avalanche flowed down Lake Creek as far as its confluence with the North Umpqua River. This is the present site of Lemolo Lake. Part of the material was diverted westward across Toolbox Meadows and continued down the drainage of Lava Creek and the Clearwater River. This fork of the avalanche came to rest about halfway between the Lake Creek drainage and Toketee Ranger Station.

It is not clear just how a glowing mass of pumice and gas could pass over the surface of a body of water such as Diamond Lake; but the evidence is clear—the amount of avalanche material exposed below Diamond Lake is sufficient to fill the lake, perhaps many times over. Two theories have been advanced, seeking to explain how this might have happened. One geologist has suggested that the first wave of pumice would have floated on the surface of the lake, providing a carpet across which successive waves flowed. The pumice is light enough to float on water; and the theory is plausible.

Another theory asserts the avalanche occurred during the winter when the lake was frozen. The rushing mass of hot gas and pumice presumably flowed over the ice, which was insulated from the intense heat by the 5-foot layer of airborne pumice that preceeded it. Adding strength to this theory is the fact that the winter winds in the Diamond Lake area blow toward the northeast, which is precisely the direction they must have been blowing at the time the airborne pumice was erupted from Mt. Mazama. As stated earlier, the airborne pumice stretches toward the northeast from Crater Lake. This theory, too, then, offers a possible answer to the puzzle.

|

| Road cut exposing charcoal logs in washed pumice deposit |

The pumice of the glowing-avalanche deposit is easily distinguished from that which earlier fell from the air. Whereas the airborne pumice is well sorted (i.e., all the particles are approximately the same size at a given point), the avalanche material consists of lumps of pumice of varying size, set in a matrix of very fine, dust-like pumice fragments. Some of the largest lumps of pumice have been found at the extreme limits of the avalanche deposits. The airborne pumice is a yellowish tan color; the avalanche pumice is usually pinkish tan. The pink coloration is the result of stains from the iron-bearing gases that it retained after coming to rest. As the glowing avalanche rushed down the stream drainage, it encountered thick forests, though timberline was then at a lower elevation than at present. The force of the avalanche bowled over even the largest trees and swept them along in the turbulent cloud. As the avalanche came to rest, the buried trees were carbonized by the intense heat retained by the pumice fragments and gases. Lumps of charcoal are found scattered through the deposit, and are exposed in road cuts near Clearwater Falls, Lemolo Lake, and White Horse Falls. This charcoal has been identified as remnants of pine and fir trees like those presently growing in the area.

Because the airborne pumice deposits and the glowing-avalanche deposits consist of soft, uncemented particles they are rapidly eroded and washed away by streams. Much of the material has been washed down the North Umpqua and Clearwater Rivers and has been redeposited in stratiform layers. Banks of washed pumice up to 100 feet thick are exposed in road cuts along the North Umpqua Highway west of Toketee Falls. A well dug at the Toketee Ranger Station cut through approximately 75 feet of this material. The washed pumice also contains charcoal fragments. These are abundant in several exposures, including those at Toketee Ranger Station and Slide Creek.

Radiocarbon dating has been performed on several charcoal specimens from the glowing avalanche deposit, though none of these was from the Diamond Lake area. The most reliable date yet obtained is 6,640 years ± 250 years B. P.1 This means the showers of pumice which fell on the Diamond Lake area, and the avalanche of scorching pumice which plunged rapidly down the drainages in the area, occurred about 6,640 years ago.

1Before Present

There is evidence that man watched the fiery holocaust in the area—at least from a distance. Charred Indian sandals have been found beneath the airborne pumice deposit near Paisley, some 80 miles east of the Crater Lake region. It is likely that some forest animals were trapped by the speeding glowing avalanche, but no remains have yet been uncovered in the Diamond Lake area.

Each day the streams remove a little more of the veiling mantle; and each new road cut exposes some new facet of the hidden past. The somber peaks and crystalline waters of the Diamond Lake area continue to reveal secrets jealously kept since their cataclysmic, formative days.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

diamond_lake_geology/sec3d.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jul-2008