|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 132—A

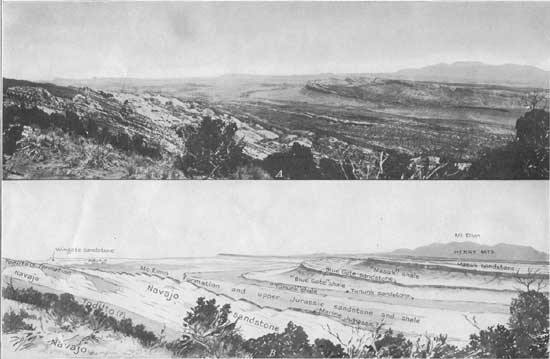

Rock Formations in the Colorado Plateau of Southeastern Utah and Northern Arizona |

SEDIMENTARY ROCKS.

(continued)

JURASSIC SYSTEM.

General features.—Red, brown, tan, and gray sandstones of Jurassic age form the most prominent outcrops in the area under consideration. The units were traced almost continuously, and their relations for this portion of the plateau were determined without question. There still exists some degree of doubt as to the proper terminology to be applied in the Jurassic section, however, and the reasons for this uncertainty will be discussed briefly.

In the eastern part of the Navajo country Gregory recognized three Jurassic formations,28 which he thought were equivalent to the La Plata sandstone of southwestern Colorado. For the lowest unit he adopted Dutton's term Wingate sandstone, considering it identical with the section in the Zuni Plateau,29 to which this name had been applied, and he called the upper formation the Navajo sandstone. In western New Mexico and eastern Arizona these two thick, cross-bedded formations are separated by beds of hard limestone and limy shale, at no place aggregating a thickness of more than a few feet, but so persistent that they were recognized as a distinct unit and named the Todilto formation, from Todilto Park, N. Mex. In his reconnaissance survey Gregory was not able to trace the Todilto continuously to the west, but along the San Juan and in the vicinity of Navajo Mountain he recognized a distinct threefold division that appeared to correspond to the three formations observed farther east. The middle unit along the San Juan contains more sandstone than the typical Todilto, but limestone and limy shale are present at numerous places, and the sandstone formations above and below appear to be identical with the Navajo and Wingate of western New Mexico. Accordingly, Gregory applied the name Todilto to the middle unit tentatively, realizing that the correlation was not certain but only very probable.30 His Wingate and Navajo of the western Navajo country correspond respectively to Powell's Vermilion Cliff and White Cliff sandstones in the region north of the Grand Canyon and Marble Canyon, but no intervening formation is recognized in that region.

28Gregory, H. E., Geology of the Navajo country: U. S. Geol. Survey Prof. Paper 93, pp. 52-59, 1917

29Dutton, C. E., Mount Taylor and the Zuni Plateau: U. S. Geol. Survey Sixth Ann. Rept., pp. 136-137, 1885.

30Gregory, H. E., op. cit., pp. 55-56.

Emery worked with Gregory in the eastern part of the Navajo country and later made a survey of the Green River Desert, east of the San Rafael Swell, where he recognized three distinct Jurassic formations and applied to them Gregory's names Wingate, Todilto (?), and Navajo.31 The Todilto (?) of Emery contains fossils and is known to be at the horizon of the marine Jurassic. He noted an apparent threefold division of his Wingate in different sections, the middle member consisting of thin-bedded sandstone and shale; but the height of these thin beds above the base of the Wingate varies at different localities, and therefore he believed that the beds were lenticular and did not represent a constant horizon. Later work, however, indicates that the beds occur at a definite horizon and that the variation, in height above the base of the Wingate merely represents a variation in thickness of that formation, perhaps due in part to the unconformity at the top of the Chinle. The thin-bedded unit was traced by Mr. Moore along the San Rafael Swell and the Waterpocket Fold, and other contributors to this report followed the beds continuously in other parts of the region, tracing them to the San Juan and to Rainbow Bridge and other localities where the beds form the unit correlated with the Todilto by Gregory. (See Pl. II.) It appears, therefore, that Gregory's usage has priority and should be retained for the present. It remains for future field work to determine the exact horizon of the Todilto at the type locality. If Gregory's tentative correlation along the San Juan should prove to be correct, then his terminology should be kept permanently and new names should be given to the formations designated Todilto (?) and Navajo by Emery. If the type Todilto is found to be at the horizon of the marine Jurassic, then Emery's tentative usage of the name will be established; but in that case his use of the names Wingate and Navajo should be reconsidered, for it appears that the name Navajo might well be retained for the sandstone that is typically exposed in Navajo Canyon and at Navajo Mountain, and the series of thin beds beneath it (Gregory's Todilto of the San Juan) deserves a new formation name.

31Emery, W. B., The Green River Desert section, Utah: Am. Jour. Sci., 4th ser., vol. 46, pp. 551-577, 1916.

In the following descriptions the three names are used in Gregory's sense, with the reservation suggested above regarding the Todilto. Emery's Todilto (?) will be referred to as "gypsiferous shales and sandstones" and his Navajo will be designated "varicolored sandstones and shales." Gregory, during field work since the publication of his reports on the Navajo country, has recognized these two units but has applied only temporary field names to them.

Wingate sandstone.—The Wingate sandstone is the most conspicuous cliff-maker in the region. (See Pls, IV, B; V, A; VI, B; VII, A; and VIII.) It is from 250 to 500 feet thick, and commonly the greater part of the total thickness appears as a single massive unit, which is cut by vertical joints and presents an impassable wall at the top of Chinle slopes. In some sections the lowermost beds are lenticular, in part conglomeratic, and apparently fill slight depressions in Chinle shale. These lower beds are obviously waterlaid. The massive, cliff-making portion, which averages about 300 feet in thickness, has indistinct and discontinuous bedding and is cross-bedded on a large scale. These structural characteristics, as well as the universal fineness and roundness of grain, suggest an eolian origin for this principal member. The only fossils reported from the formation are a few dinosaur tracks observed by Mr. Miser on surfaces of the lower lenticular beds at a locality several miles above the mouth of San Juan River.

The color of the sandstone on exposed surfaces gives the cliffs a striking appearance even in a "painted desert"; but the color is reddish brown rather than vermilion as suggested by the old formation name. On unweathered surfaces the rock is typically buff-colored, the darker shade ordinarily seen on cliffs resulting from weathering.

This sandstone forms the Vermilion Cliffs in western Kane County, Utah. Together with the overlying Todilto (?) formation it corresponds in age to Gilbert's Vermilion Cliff group in the Henry Mountains.32 But the massive sandstones of the Vermilion Cliffs near Lees Ferry, Ariz., and of the Echo Cliffs are made up not only of the Wingate sandstone but of the Navajo sandstone; the Todilto (?) formation has not been recognized and is apparently absent there.

32Gilbert, G. K., Report on the geology of the Henry Mountains, pp. 5-7, U. S. Geog. and Geol. Survey Rocky Mtn. Region, 1880.

Todilto (?) formation.—The character of deposits in the formation tentatively correlated with the Todilto varies considerably both vertically and horizontally; but the formation is sharply distinguished from the underlying and overlying sandstones by comparative thinness of beds and by undoubted evidence of deposition in water. Measured sections of the formation in the region under discussion range from 125 to 249 feet in thickness. Layers of flint limestone and of calcareous shale are present in most localities, except perhaps to the north and west, but everywhere sandstone makes up the greater part of the thickness. The lower part is commonly very lenticular and contains considerable conglomerate with small sandstone pebbles. These beds, as well as others higher in the formation, were probably deposited by streams with rapid, shifting currents. The layers of shale and limestone are found for the most part in the middle and upper portions. The shale forms a zone of weakness that commonly causes the overlying Navajo sandstone to retreat behind the Wingate cliffs, leaving benches floored by the lower resistant sandstone of the Todilto (?). (See Pls. VIII, B, and IX, A.) The limestone beds are lenticular and range from a few inches to 2 feet in thickness. The material is dense, hard, and cherty and is probably of fresh-water origin.

|

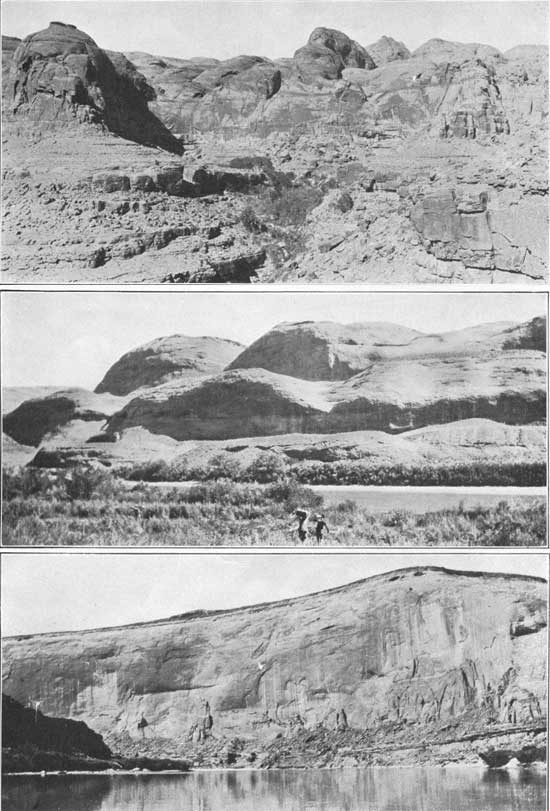

| PLATE IX—A (top), VIEW LOOKING NORTHEAST TOWARD WILSON MESA FROM POINT ON WILSON CREEK NEAR SAN JUAN CANYON, UTAH. Showing bare domes and "mosques" of Navajo sandstone. Todilto (?) formation underlies platform in foreground. Photograph by Robert N. Allen. B (middle), VIEW LOOKING ACROSS COLORADO RIVER OPPOSITE SMITHS FORK, UTAH. Showing colossal domes of Navajo sandstone. Photograph by Sidney Paige. C (bottom), SHEER CLIFF OF NAVAJO SANDSTONE AT WARM SPRING CREEK ON COLORADO RIVER, UTAH. Photograph by Sidney Paige. |

In some sections the transition from the massive Wingate to the thinner beds above appears to be gradual, but at many localities along the Colorado a distinct erosional unconformity separates the two formations, lenticular fluviatile beds filling valleys on the surface of the Wingate. In a cliff the lower sandstones of the Todilto (?) are readily distinguished from the light-colored Wingate by their dark-maroon or reddish-brown color. At higher horizons the Todilto (?) beds vary in color through shades of brown, tan, and lavender. The limestone layers are usually gray.

Navajo sandstone.—Many of the picturesque and grotesque erosion forms common in southern Utah and northern Arizona are carved in the Navajo sandstone of Gregory, which is essentially equivalent to Gilbert's "Gray Cliff group" and to Powell's White Cliffs sandstone. It is exposed over large areas along the Colorado and the San Juan, in the Waterpocket Fold and the Circle Cliffs, and farther west in south-central Utah and forms great tracts of almost impassable badlands, in which domes, "mosques," and "minarets" are common features. (See Pls. VI, B; VIII, and IX.) Caves, alcoves, and arches are conspicuous in cliffs of this sandstone, and it forms a number of natural bridges, notably the Rainbow and Owl bridges, near Navajo Mountain.

The thickness varies between wide limits, reaching a reported maximum of 1,800 feet in western Kane County, Utah, and a minimum of about 500 feet south of the Henry Mountains. Along the Colorado and the San Juan the thickness is commonly from 600 to 800 feet, but a few sections measure 1,000 feet. From the Waterpocket Fold westward the thickness is generally above 1,000 feet. There is also a marked change in color from east to west. From the Waterpocket Fold westward a large part of the formation is commonly gray or creamy white, whereas in the region south of the Henry Mountains, around Navajo Mountain, at Lees Ferry, and in Comb Ridge the sandstone is typically tan or buff.

This sandstone is frequently cited as a typical eolian deposit. Cross-bedding of the "tangential" type and on a very large scale characterizes the greater part of the formation, and the laminae of the cross-bedded structure show the abrupt and repeated truncation so commonly seen in "living" sand dunes. True bedding planes are present but not distinct, so that the entire formation stands in some cliffs with the appearance of a single massive layer. Beds of compact limestone from 2 to 5 feet thick lie at several horizons but chiefly in the upper half of the formation. These beds extend laterally from a few hundred feet to half a mile and probably represent deposition in shallow pans or basins. In view of the general high porosity of the sandstone, it would seem that these deposits required a high ground-water level, at least locally.

Gypsiferous shales and sandstones.—The series of beds here designated gypsiferous shales and sandstones is exposed at Bluff, in the Henry Mountains, and farther north, between Kaiparowits Plateau and Escalante River and along the Colorado below the mouth of the San Juan almost to Lees Ferry. (See Pl. X, A.) It is also found west of the Kaiparowits Plateau at several localities, notably in western Kane County, Utah, where it is apparently represented by about 100 feet of bluish-gray marl with considerable gypsum. In typical sections the beds consist of gypsiferous shale intercalated with layers of sandstone and some limestone, with an average total thickness of about 75 feet. In 1918 W. B. Emery33 studied these beds in the Green River Desert and reported the occurrence of marine Jurassic fossils in some of the limestone layers. This fossiliferous series had been noted previously by Gilbert34 and by Lupton.35 In some sections there are indications of an unconformity between these beds and the underlying Navajo sandstone.

33Op. cit., pp. 568-569.

34Gilbert, G. K., Geology of the Henry Mountains, p. 6, 1880.

35Lupton, C. T., U. S. Geol. Survey Bull. 628, p. 24, 1916.

The beds deserve a formation name, but it appears best to postpone assigning a definite name until the Todilto problem, discussed above, has been finally solved by further field work.

Varicolored sandstones and shales.—The thick series of beds here termed varicolored sandstones and shales includes the greater portion of the rocks in Gilbert's "Flaming Gorge group." These beds reach a maximum thickness of approximately 1,430 feet in the Waterpocket Fold. (See Pl. X, A.) Along Colorado River between the mouth of the San Juan and the Crossing of the Fathers the series appears to have a thickness as great as 500 feet, and near Bluff it is from 170 to 270 feet thick. Complete and partial sections are exposed at many localities south and west of the Henry Mountains and northeast of the Kaiparowits Plateau. The series contains a massive cross-bedded sandstone member, tan, red, and gray, which has some resemblance to the typical Navajo sandstone. Other parts of the section consist of thin-bedded sandstone, much of it shaly. East of the Waterpocket Fold the predominant colors are red and tan, but in western Kane County, where the stratigraphic position of the series is occupied chiefly by sandy shale, many of the beds are gray and bluish gray.

Emery considers that this series of beds, as well as those at the horizon of the marine Jurassic, corresponds to the La Plata sandstone of Cross. Gregory limits the La Plata group to his Wingate, Todilto, and Navajo formations.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pp/132-A/sec2d.htm

Last Updated: 08-Aug-2008