|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

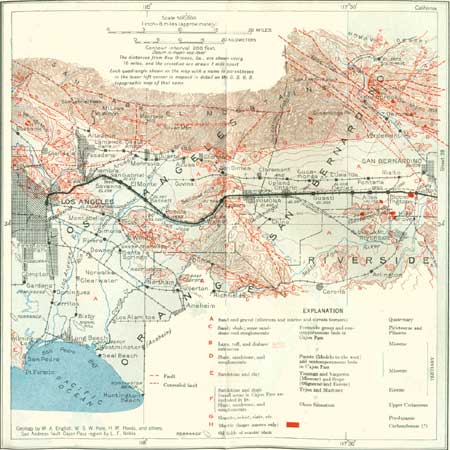

SHEET No. 29 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

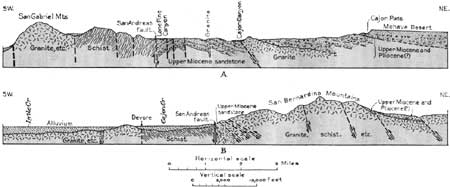

Northwest of Colton is Cajon Pass (see fig. 66), a great break between the San Gabriel Mountains on the west and the San Bernardino Mountains on the east, which is utilized by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway and by the highway that crosses the Mohave Desert. Through it also passed the Mormon trail, much used by the gold seekers of 1849. The pass is due to erosion along several parallel faults, of relatively recent age geologically, that cross diagonally the axis of the general mountain range extending across southern California. These faults include the southern extension of the San Andreas fault, movement along which in 1906 caused the San Francisco earthquake They define the north side of the San Gabriel Mountains, and southeast of the pass they extend eastward for many miles along the south foot of the San Bernardino Mountains. There are several planes of movement, not far apart, with huge slivers, or narrow blocks, of schist and soft sandstone between them. (See pl. 46, B.) The erosion of the sandstone on the down-thrown blocks is the principal cause of the pass. (Noble.)

|

| FIGURE 66.—Sections northwest of San Bernardino, Calif. A, Through Cajon Pass; B, near Devore siding. After Noble. For location see sheet 29. |

Near Redlands the faults present many features indicating recent movement, notably at one place where a ravine has been offset abruptly. The movement was mostly vertical, but in some of the faults there has been a horizontal displacement. For some distance a strip of Tertiary strata lies on one of the slivers between the faults, bordered on each side by the old schists. In general in this vicinity the faults are bordered on the north by sandstone of Tertiary age lying on gneiss or schist, and on the south side is schist more or less heavily covered by young gravel. (Noble.)

Although the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains contain similar rocks, are separated only by Cajon Pass, present identical relations to the valley of southern California and to the Mohave Desert, and are both uplifted fault blocks, they are very dissimilar in configuration. The San Gabriel Mountains are deeply cut by canyons containing graded streams and are made up of separate sharp peaks and knifelike ridges of various heights; no level areas remain, either about the summits or in the valley bottoms. The higher part of the San Bernardino Mountains has a very different character, for its west end, at least, presents a strikingly level sky line, mostly at elevations from 5,000 to 6,000 feet, and the range contains many broad valleys, some with meadows and lakes, separated by rolling ridges, a topography of an old and well-reduced type. According to recent observations by Noble this condition is due largely to the relatively recent removal of Tertiary deposits from the plain on which they were laid down. Remnants of these strata remain in places. To the east, where the elevation increases, San Bernardino Mountain and San Gorgonio Mountain rise considerably above the general level. Along the lower margins of the range the forms are strikingly new, and several of the streams are not reduced to grade but after meandering through the broad uplands plunge over falls into steep canyons in the front of the range. These differences in the configuration of the two ranges are not related to rock texture, drainage pattern, or difference in precipitation; it is suggested that the San Bernardino fault block was uplifted much later than the block constituting the San Gabriel Range, which has preserved none of these old forms. (Mendenhall.)

|

Bloomington. Elevation 1,090 feet. New Orleans 1,948 miles. |

Bloomington, a small place 4 miles west of Colton, is in the midst of a thriving irrigation district with many groves of oranges and olives. To the north is a fine view of the San Gabriel Mountains,90 with their imposing high peaks and deeply incised canyons. Along the foot of the range is the main fault, but it is everywhere buried under valley fill. Just south of Bloomington are the Jurupa Mountains, rising about 1,000 feet above the plain; they consist of quartzite, schists, and crystalline limestones, all metamorphosed sedimentary deposits, penetrated by granitic and other igneous rocks. Their length is about 5 miles, and they are surrounded by valley lands. Beyond the west end of this range is the north end of the high Santa Ana Mountains,91 which extend southeast from Corona.

90The San Gabriel Mountains consist of granite rocks of several kinds and a variety of other crystalline rocks, mainly schists, some of which were originally shales and sandstones but have been altered (metamorphosed) by great igneous intrusions and compression. It is believed that the range was uplifted in greater part in late Tertiary time. Apparently the uplift consisted of the rise of a huge block of the earth's crust along fault lines mostly trending N. 60° W. The main block is traversed by minor faults which make the structure very complex.

91In the Santa Ana Mountains the oldest rocks are Triassic slates and sandstones with some limestone lenses, intruded by dikes of andesite. They are overlain unconformably by a coarse conglomerate and in places by basic lavas and tuffs, and all are cut and altered greatly by masses of andesite, granodiorite, and diorite which have been intruded in a molten condition. Next above there is a westward-dipping succession of Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary strata. In general, the mountains consist of a tilted fault block with local flexures. There has been a long series of repeated uplifts, but in the development of the present topography the hardness of the rocks has been the principal factor. Some of the lower terraces are marine. (B. N. Moore.)

|

Guasti. Elevation 958 feet. Population 164. New Orleans 1,959 miles. |

From Bloomington to Ontario there are several settlements occupied with the extensive culture of grapes, lemons, peaches, and other fruits. In this region the San Bernardino Plain is more than 20 miles wide, extending from the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains to the Santa Ana River which flows near its southern margin. It is bordered on the west by the San Jose and Puente Hills, which make a barrier trending north-northwest, beyond Pomona. To the north near Guasti are fine views of Cucamonga Peak (elevation 8,911 feet), one of the high summits of the southern ridge of the San Gabriel Mountains, and the still higher San Antonio Peak (elevation 10,080 feet) is farther back on the northern sky line. Deep canyons lead out of these mountains at short intervals, and most of them contain streams whose water, if not diverted by irrigation ditches, sinks at the mouths of the canyons and passes as a general underflow into the gravel and sand of the slope beyond. In times of freshet the streams flow greater or less distances across the slope, carrying much sediment, which is dropped as the water spreads out on the plain. Occasional great floods cross the plain, but much of the large volume of water they carry at such times is absorbed by the porous gravel of the stream beds. The courses of these ephemeral streams across the plain are marked by dry washes, usually shallow sandy channels, many of them splitting up irregularly and some of the branches rejoining. One effective method of conserving water in this region, where it is so valuable, is to divert flood waters near the canyon mouth, causing them to spread out widely over the coarse deposits, where they sink, thus adding to the volume of underflow tapped by many wells.

|

Ontario. Elevation 991 feet. Population 13,583. New Orleans 1,963 miles. |

Six miles northwest of Ontario is the mouth of San Antonio Canyon, one of the larger drainage outlets from the San Gabriel Mountains, which furnishes considerable water for irrigation. On the plain the creek bed spreads into half a dozen irregular "washes," which are crossed by the railroad near Ontario. From the gravel and sand under the plain a large amount of water is pumped for irrigation. The water is conveyed in canals lined with concrete and is distributed in underground pipes so as to prevent loss by leakage and evaporation.

Ontario, with its companion settlements, North Ontario, San Antonio Heights, and Upland, extends widely across the valley slope and up the foothills of the mountains. The settlement is traversed by a handsome tree-shaded boulevard, Euclid Avenue, which runs north to the foot of the mountains. Ontario is surrounded by many orange and lemon groves and other products of irrigation, and one of its chief industries is a fruit-canning establishment, claimed to be the largest in the State.

|

Pomona. Elevation 855 feet. Population 20,804. New Orleans 1,967 miles. |

Pomona is a commercial, residential, and educational center, built on the western margin of the plain that extends from San Bernardino to the San Jose and Puente Hills. It is surrounded by extensive groves of oranges and other fruits and produces large amounts of walnuts and grapes. About Pomona were grown the first oranges shipped from California. The underground water supply is utilized for irrigation by pumping from hundreds of wells. Much attention has been given to making the landscape lovely with trees and gardening. At Claremont, not far north, are the Claremont Colleges, one of the most beautiful and outstanding institutions of learning in the coast region, and the Greek Theater, which seats 4,000.

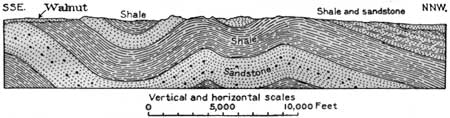

Three miles west of Pomona the railroad passes over a low divide between the San Jose and Puente Hills and descends the canyon of San Jose Creek. The San Jose Hills, to the north, consist mainly of a thick succession of shales and sandstones of the Puente formation (middle and upper Miocene). At their northeast end, 2 miles northwest of Pomona, there is granite92 overlain by lava flows and volcanic tuffs and agglomerates at the base of the Tertiary section, and a similar succession on the south side of the railroad constitutes the northeast corner of the Puente Hills. A section of the San Jose Hills north of Walnut is given in Figure 67.

92The granite is well exposed in Ganesha Park, in the northwestern part of Pomona. It is much weathered, but its coarse crystalline texture is apparent. West of Pomona on both sides of San Jose Creek the granite is overlain by igneous rocks of Tertiary age containing flows of white, purple, and brown lavas and intrusive sills of dark basic rocks. Agglomerate, vesicular flows, and tuffaceous sandstone are also found in the area north of San Jose Creek constituting the east end of the San Jose Hills. South of Spadra a few blocks of sandstone are included in the intrusive rocks, and there is a vein of coarse calcite traceable for a mile or more, which was burned for plaster by the early Spanish settlers. (See p. 293.)

|

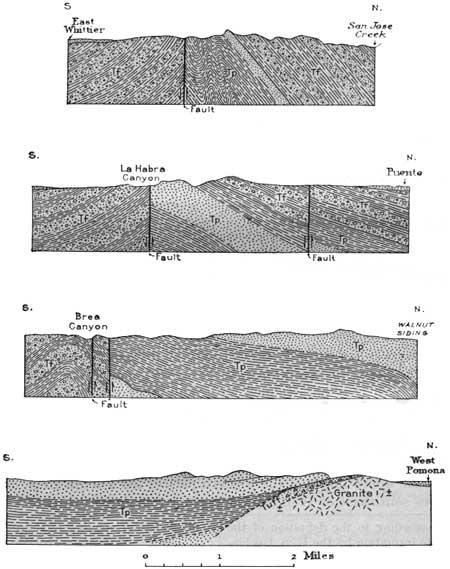

| FIGURE 67.—Section of San Jose Hills about 7 miles west of Pomona, Calif. After English and Kew. All Puente formation. |

The Puente Hills consist of sandstones and shales of the Puente formation,93 2,600 to 3,400 feet thick (middle and upper Miocene), with smaller exposures of underlying and interbedded shales, having the relations shown in Figure 68. The granites and slates of pre-Cretaceous age at the east end are separated from the sandstone member of the Puente by tuffs and tuffaceous sandstones, somewhat as shown in the lowest section in Figure 68. The Puente formation of this region (regarded as equivalent to the Modelo formation of the region to the west) is made up of an alternating succession of coarse and fine materials with many thick members of shale and sandstone. The upper shale includes beds carrying the remains of minute marine plants and animals, principally diatoms and Foraminifera; the more richly diatomaceous portion is nearly white and of chalky texture. At the west end of the hills, south and west of Puente, overlying shales and sandstones of the Fernando group (Pliocene) are extensively exposed, and they are dropped by a fault extending along the south side of the Puente Hills, passing just north of Whittier and along La Habra, La Brea, and Olinda Canyons. The Fernando group carries a fauna of marine shells of Pliocene age and is nearly 5,000 feet thick. (English and Kew.)

93According to the definition of the Puente formation by the U. S. Geological Survey, in the Puente Hills and Los Angles district it comprises the following members:

Upper shale, 300 to 2,000 feet. Earthy chalky shale and sandy gray shale, weathering pink to chocolate-brown, with a few beds of fine yellow sandstone. Is overlain unconformably by Fernando group.

Sandstone member, 300 to 2,000 feet. Moderately coarse gray to tawny-yellow thick-bedded sandstone with beds of shale; some conglomeratic members containing granite boulders.

Lower shale, 2,000 feet. Chiefly earthy shale, mostly gray to black, including thin beds of fine-grained sandstone from top to base and lentils of limestone.

|

| FIGURE 68.—Sections across Puente Hills, Pomona to Whittier, Calif. After English and Kew. Tf, Fernando group (Pliocene and Pleistocene), Tp, Puente formation (Miocene) |

On the upper slopes of the western part of the Puente Hills, about 5 miles southwest of Walnut, was the old Puente oil field, one of the earliest fields discovered in California. The first well was completed in 1880, and at the end of 1912 there were 470 producing wells with an annual output of 7,000,000 barrels and an aggregate production of 41,000,000 barrels. The wells were in the outcrop area of the thick body of shales constituting the lower half of the Puente formation, and the oil is thought to have migrated from the great oil fields to the southeast. The depths of the wells were mostly from 1,000 to 2,000 feet. The large oil production of this general region now comes from the Santa Fe, Whittier, Brea Canyon, Coyote Hills, and other fields along the south slope of the Puente Hills or south of them.

|

Puente. Elevation 320 feet. Population 1,034. New Orleans 1,982 miles. |

Puente is the center of a great walnut district which produces more than 13,000,000 pounds of walnuts a year (1929). Near Puente the railroad leaves the valley of San Jose Creek and the Puente Hills and passes into the wide basinlike plain bordering San Gabriel Wash, into which flows the San Gabriel River, a stream that rises in deep canyons far back in the San Gabriel Mountains. This wash is crossed a mile west of Bassett, but there is usually little water in it here except during rainy seasons. The river water is used for irrigation, but much of it is underground, where it is available for pumping. Some of this underflow comes out again in Lexington Wash, near El Monte. In times of freshet a large volume of water passes down San Gabriel Wash, as may be inferred from the large boulders in its bed. These boulders are crushed for road material.

From Bassett to San Gabriel the railroad goes northwest across a broad plain, most of which is in a high state of cultivation, with numerous fruit and walnut orchards, beautiful gardens, and verdant fields, all irrigated by water pumped from the underflow.

As the train progresses northwestward the San Gabriel Mountains are approached and there are fine views, notably of San Gabriel Peak (elevation 6,152 feet). This great mountain range consists of a huge block of the earth's crust uplifted along profound breaks, one of which, the Sierra Madre fault, follows the south foot of the range, and another, the San Andreas fault, extends along its northern margin. These are very recent faults, for the main upheaval was at the end of Tertiary (Pliocene) time. Doubtless there was a prior mountain range in front of the site of the present San Gabriel Mountains, which furnished sediments to the pre-Pliocene formations, but the form and relations of mountains and plains at that time can hardly be conjectured. An uplift of this kind may have progressed very slowly. There was not only the general axial uplift of the range but cross faulting, which has broken the main block into huge fragments with varying degrees of tilt and amount of uplift. The planes of the main faults dip steeply to the south, at least in the west end of the range, so that the granite and gneiss of the range are relatively thrust over the strata of Tertiary age, which are considerably flexed and in places also faulted. (M. L. Hill.) In the portion of the range north of Los Angeles the rocks are schist, quartzite, and marble, old sediments greatly metamorphosed and penetrated by a large amount of igneous rocks. Granite invades the metamorphic rocks very extensively, and there are also large masses of diorite and granodiorite and some hornblendite. (W. J. Miller.)

|

San Gabriel. Elevation 415 feet. Population 7,224. New Orleans 1,992 miles. |

The old San Gabriel Mission is a few rods south of the tracks at San Gabriel station. It was the fourth of the many missions established by the Franciscan friars between San Diego and San Francisco and is in an excellent state of preservation. It was started by Padres Cambón and Somera, under the direction of Fray Junípero Serra, September 8, 1771, and the building is typical of the architecture introduced by the friars. Early in its history a ditch was built to bring water for irrigation and for horses, cows, pigs, sheep, and chickens. The region was then inhabited by Indians, who were stolid, mild mannered, and rather ugly in features. They were not forcibly Christianized but were treated so well that many desired to live at the missions and be instructed. As the community prospered and settlers came in, the poor little hovels of adobe and reeds were replaced by finer buildings. The present village is in the midst of groves of oranges, avocados,94 and walnuts, with many fine gardens. In 1850 Roy Bean, later famous as "the dispenser of the law west of the Pecos" at Langtry, Tex. (see p. 83), ran a dance hall and gambling saloon at San Gabriel, at that time a typical frontier town. The history of the beginnings of California is pictured yearly in the Mission Play by the poet John Steven McGroarty, done in the beautiful playhouse adjoining the San Gabriel mission.

94The fruit called aguacate by the Mexicans and other Spanish-speaking people now has the commercial name "avocado" to replace the former "alligator pear," which was a decided misnomer, as the fruit is not a pear and is in no way associated with alligators.

|

Alhambra. Elevation 456 feet. Population 29,472. New Orleans 1,995 miles. |

Alhambra is an extensive settlement largely devoted to the growing of fruits, vegetables, and walnuts. There is a branch railroad from Alhambra to Pasadena, a city of 76,086 inhabitants a few miles to the north. This large and beautiful city is a most interesting business, residential, and educational center. In the eastern part is the California Institute of Technology, founded in 1891, which now includes among other buildings or departments the Bridge Laboratory of Physics, the High Potential Research Laboratory, the Gates Chemical Laboratory, the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory, the Seismological Research Laboratory, the Dabney Hall of Humanities, and the Kerckhoff Biological Laboratories. Near by is the great Huntington Library and Art Gallery. The observatory on Mount Wilson, one of the units of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, is equipped with the world's largest reflecting telescope.

Pasadena lies in a "rincon," or corner, between hills and mountains, so that it has protection from winds and a slightly greater rainfall than some of the regions farther east and south. The name is an Indian word meaning crown of the valley. To the north are the high San Gabriel Mountains, with two conspicuous summits, Mount Lowe (elevation 5,650 feet) and Mount Wilson (5,750 feet), from both of which there are extensive views of the Los Angeles Plain. (See pl. 47).

|

| PLATE 47.—LOS ANGELES PLAIN, CALIF., FROM ECHO MOUNTAIN. Looking southwest. Pasadena in middle ground; Los Angeles at right; San Pedro in distance. |

The Repetto Hills west and south of Alhambra consist of sandstone, conglomerate, soft siltstone, and shale of Miocene, Pliocene, and possibly Pleistocene age, flexed in basins and arches. Part of the shale of upper Miocene age is diatomaceous. These rocks are of marine origin and indicate that during the later part of Tertiary time the region was submerged by the sea at intervals, and sand and mud were deposited in wide estuaries and along beaches. There was a long epoch of general subsidence, so that a great thickness of these materials accumulated. They have since been consolidated, uplifted, flexed, and faulted, and later terraces and plains have been developed on their surface. (Reed.)

After passing out of this narrow belt of hilly country the railroad enters the coastal plain that extends south and west to the Pacific Ocean. This plain consists of lowlands abruptly margined to the north by the Santa Monica Mountains, Repetto Hills, Puente Hills, and Santa Ana Mountains. Much of the region is a plain sloping gently seaward, but its continuity is interrupted by hills and ridges of considerable prominence, such as the Baldwin Hills, Dominguez Hill, and Signal Hill. In general it is floored with alluvium derived from the adjoining highlands and the mountains to the north. In a few places, however, the rocks have not yet been covered by alluvium. The plain is widest in the Los Angeles region, where it extends 25 miles south from the Santa Monica Mountains and with an area of nearly 2,000 square miles constitutes the combined delta of the Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana Rivers. At its inner edge its elevation is mostly from 200 to 300 feet, and the seaward slope is 10 to 20 feet to the mile. This plain, with its fertile soil and delightful climate, is covered with settlements, cultivated fields, vineyards, and vast orchards of oranges, lemons, walnuts, olives, and other fruits. Shade trees and flowers are extensively cultivated. To this wealth of resources on the surface is added a large production of petroleum, which has been developed most profitably at many places.

The Los Angeles River is crossed in the eastern outskirts of the city of Los Angeles, and the train proceeds slowly through streets for about 3 miles to the depot. Most of the city is built on low river terraces and on the inner edge of the coastal plain, but the newer sections extend onto the hills of folded and faulted Tertiary sandstone and shale that rise to the north. The Los Angeles River, like many other streams of the Southwest, is ordinarily of small volume, but during heavy rains it is considerably swollen, and at times it becomes a deep torrent capable of doing considerable damage.

|

Los Angeles. Elevation 253 feet. Population 1,235,048. New Orleans 2,002 miles. |

Los Angeles is the largest city of the Southwest, in area, population, and business. Founded in 1781 by a garrison of Mexican soldiers the mission of San Gabriel, in 1831 it had a population of 770, and as late as 1880 it was an easy-going semi-Mexican town of 12,000 inhabitants centered about the old plaza with the mission church of Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles (Our Lady the Queen of the Angels), from which the City takes its name.

At La Mesa battlefield, now the stockyards on Downey Road, there was on January 9, 1847, a battle between the Americans and Californians which resulted in the capture of Los Angeles by the American forces.

Among many historical episodes in Los Angeles one of the most important was the truce signed on January 13, 1847, by Gen. Andrés Pico, which when ratified gave to the United States all of the territory west of the Rocky Mountains south of Oregon. This event occurred at Campo de Cahuenga, now 3919 Lankershire Boulevard. At the southeast corner of Los Angeles and Aliso Streets is the building in which General Frémont had his headquarters while he was military governor of California, and here the city of Los Angeles was organized in 1850.

With the coming of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway in November, 1885, homeseekers began to arrive, and a great increase in property values and growth of the city followed. The census showed that Los Angeles made a greater percentage of increase in population from 1880 to 1900 than any other city in the United States, and there has been a remarkably rapid increase since that time, amounting to nearly 115 per cent in the decade 1920-1930. The city is the largest in area in the United States, comprising within its limits 442.5 square miles. In addition to the salubrity of its climate, which attracts citizens from all over the United States, two important factors in its growth have been the generation of electricity from mountain streams as far as 226 miles away and the availability of cheap petroleum fuel. The economical power thus available has developed a very large manufacturing center.

Los Angeles has had to provide a vast amount of water for its rapidly growing population. At first local supplies were used, but later an aqueduct was constructed to bring water from Owens Valley, 226 miles distant, at a cost of about $25,000,000. Its capacity is 250,000,000 gallons a day. As still more water will be required in the future, it is planned to bring in a supplemental supply from the Colorado River at Parker after the Boulder Dam is completed. (See p. 241.)

Los Angeles County, with an area of only 4,115 square miles, claims to be the richest county in the United States in value of farm property and agricultural products. According to the United States census reports it produces more than one quarter of the oranges, lemons, and walnuts (nearly 20,000,000 pounds), and more than 10 per cent of the grapefruit (157,500 boxes) grown in the State. The milk production in 1929 was more than 47,000,000 gallons. The mean annual temperature of Los Angeles is 62°.

The harbor at San Pedro, called the Port of Los Angeles, on the ocean 25 miles south of the center of the city, has a large coast and trans-Pacific trade. Its exports in 1929 were valued at $166,328,683 and the imports at $63,685,483 (U. S. Department of Commerce). Los Angeles has four large educational institutions—the University of Southern California, the University of California at Los Angeles, Loyola College, and Occidental College. The Public Library is a handsome edifice and, besides the usual material, contains a large collection of hooks of reference.

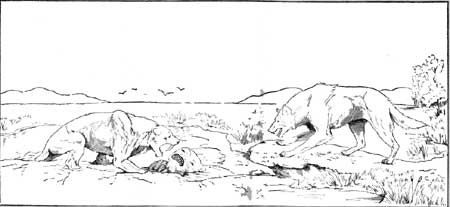

The Museum of History, Science, and Art in Exposition Park has fine collections in many fields and controls the remarkable fossil bone deposits in the asphalt springs of Rancho La Brea (pl. 48, B), about 8 miles directly west of the center of the city. These springs of tarry material due to seepages of petroleum which have oozed up from an underlying stratum have been for centuries most effective animal traps. The asphalt has accumulated to depths of 15 to 30 feet and has preserved the bones of thousands of extinct as well as modern animals which were caught in its sticky pools.95 The skeletons of elephants, camels, ground sloths, lions, saber-toothed tigers, wolves, bears, and myriads of smaller animals, including 50 species of birds, have been dug out and set up in the museum. (See fig. 69.) Carnivorous quadrupeds predominated, a fact which indicates that animals venturing out on the seemingly solid surface were caught in the viscid asphalt and served as a bait to lure their bloodthirsty neighbors, who in their turn were also trapped and unable to extricate themselves. These animals lived mostly during the Pleistocene epoch, when the northern part of this continent was buried under great fields of ice, but some of them represent later times. In one pit was found a skull of a human being, who may have lived 10,000 years or more ago, contemporaneously with some of the later animals now extinct, but is regarded as belonging to a later date than most of the animals.

95According to Stock, the most abundant mammals are the saber-toothed tiger (Smilodon californicus) and the dire wolf (Arenocyon dirus), which are represented by thousands of bones. There were also the great lionlike cat (Felis atrox), the coyote (Canis ochropus orcutti), and the short-faced bear (Tremarctotherium californicum). Among the herbivores were the mammoth (Archidiskodon imperator), mastodon (Mammut americanum), horse (Equus occidentalis), bison (Bison antiquus), camel (Camelops hesternus), antelope (Capromeryx minor), and several kinds of ground sloths (Mylodon harlanii, Nothrotherium shastense, and Megalonyx jeffersonii). Among the great numbers of condors, vultures, eagles, and hawks is the largest bird of flight, a condorlike vulture (Teratornis merriami).

|

|

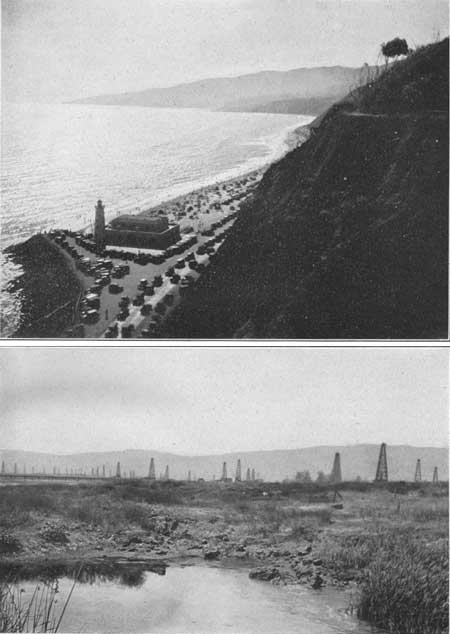

PLATE 48.—A (top), SHORE OF THE PACIFIC OCEAN AT SANTA

MONICA, CALIF.. B (bottom), ASPHALT PITS AT LA BREA, IN THE WESTERN PART OF LOS ANGELES, CALIF. Oil field in middle ground; Santa Monica Mountains in distance. |

|

| FIGURE 69.—Restoration of saber-toothed tiger, sloth, and dire wolf at La Brea, Calif. By E. Christman. |

The Los Angeles region is underlain by a thick succession of Tertiary and Cretaceous strata, some of them deeply buried and others presenting prominent outcrops, especially in the hills and mountains. They are flexed, tilted, and faulted and vary considerably in character from place to place. The eastern part of the Santa Monica Mountains, projecting into the northern part of the city, contains an extensive uptilted succession of the rocks that underlie the region. At the base are old slates and schists (Triassic?) cut by granites and granodiorites, similar to those in some other ranges of southern California. They are overlain by a thick body of conglomerate, sandstone, and shale of Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary age.

Formations in Santa Monica Mountains

[H. W. Hoots]

| Formation | Thickness (feet) |

Age |

| Shale, with beds of sandstone and ash (Modelo formation). | 4,500 | Upper Miocene. |

| Unconformity (folding, faulting, and basalt intrusions). | ||

| Sandstone, conglomerate, shale, basalt flows, and other volcanic rocks (Topanga formation). Basal 1,000 feet of conglomerate east of Cahuenga Avenue may be vaqueros. | 4,500-7,500 | Middle Miocene. |

| Light-gray and red conglomerate (Vaqueros? and Sespe? formations). | 3,500-4,000 | Lower Miocene and Oligocene(?). |

| Unconformity. | ||

| Shale and sandstone; some fossiliferous sandstone (Martinez formation). | 250+ | Lower Eocene. |

| Conglomerate, sandstone, and dark shale, fossiliferous (Chico formation). | 8,000± | Upper Cretaceous. |

In the hilly region southeast of the Santa Monica Mountains, and mainly in the east-central part of Los Angeles, younger formations are also present, notably sandstones, conglomerates, and clays of Pliocene age, which overlie the Miocene beds. These are in turn overlain unconformably by the terrace and alluvial deposits of the Los Angeles Plain, above referred to.

The east end of the Santa Monica Mountains is an open anticline, the axis of which is in a broad central area of Santa Monica slate (Triassic?) and plunges westward from the main granite mass just north of Hollywood. Although the general structure is anticlinal, the original folding is much complicated by faults, flexures, and igneous intrusions. Post-Modelo flexing resulted in widespread anticlinal uplift. In the Martinez formation, and possibly also in the Chico formation, are prominent reefs of limestone 50 to 60 feet thick, the largest one being 500 feet long. (Hoots.) The Santa Monica Mountains extend to the Pacific Ocean at Santa Monica. (See pl. 48, A.)

In the central part of Los Angeles are many exposures of Miocene beds, including shale filled with diatom remains. On Hill and First Streets above the tunnel are exposures of these shales overlain by dark, massive sandy shale of Pliocene age. Good sections of the Topanga formation (middle Miocene) appear on Glendale Boulevard between the Los Angeles River and Los Angeles, where the formation is 2,000 feet or more thick and the beds dip to the south. A conspicuous Miocene sandstone is exposed in Elysian Park. The general structure about Los Angeles is that of a syncline or basin bordered in part on the north and east by faults.

At Elysian Park, along the west side of the Los Angeles River, the railroad cuts expose sandstones of middle Miocene age overlain by upper Miocene shales. These beds are on the south limb of an extensive anticline whose axis lies in the bed of the river farther north. On Fifth Street, opposite the Public Library, upper Pliocene fossiliferous beds are well exposed. The strata east of the river consist mainly of highly folded middle and upper Miocene beds. (Kew.)

The hills in northern Los Angeles and western Alhambra consist of a thick succession of Miocene, Pliocene, and Pleistocene strata comprising conglomerate, sandstone, siltstone, and shale. In the upper Miocene are many beds of siliceous and diatomaceous shale. The total thickness of these strata is apparently 11,000 feet. They lie on the older granites and metamorphic rocks. The Miocene rocks are exposed in many street cuts east of Lincoln Park adjacent to Valley Boulevard. Upper Miocene (Puente) shale and interbedded sandstones are exposed near City Terrace. (R. D. Reed.)

In the central part of Los Angeles is a belt of petroleum-producing territory 5-1/2 miles long, covering an area of 2 square miles. Here hundreds of derricks have been erected in close proximity to dwellings. This field was discovered in 1892 by a 155-foot shaft sunk near a small deposit of brea or asphalt on Colton Street. The first good strike of petroleum was made in a well on Second Street, and by the end of 1894 there were 300 producing wells from 500 to 1,200 feet deep. The wells have been small producers, averaging 2-1/2 barrels a day each by pumping, and now much of the area is drained of its oil. The Salt Lake field is also within the city limits, about 4-1/2 miles west of the business center. It was started in 1901 and has been a notable producer, having 700 wells in 1914. The wells are mostly from 1,200 to 3,000 feet deep, and in most of the area there has been considerable gas, which caused the wells to gush in the early part of their life. The average production per well was 23 barrels a day, and the total production from 1894 to the end of 1931 was over 60,000,000 barrels. (Hoots.) The oil has been mainly useful for fuel. The petroleum in the Los Angeles district is derived largely from the upper 500 feet of the Miocene and the basal beds of the Pliocene. The oil pools are thought to be related to slight arching along the younger displacements. (Eaton.) Faulting has had much to do with the accumulation of the oil. The most productive fields are on anticlines having the form of elongated domes, but some of the folds are of the plunging variety, with their upper ends sealed by asphalt or by an overlapping impervious bed. (Kew.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec29.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007