|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

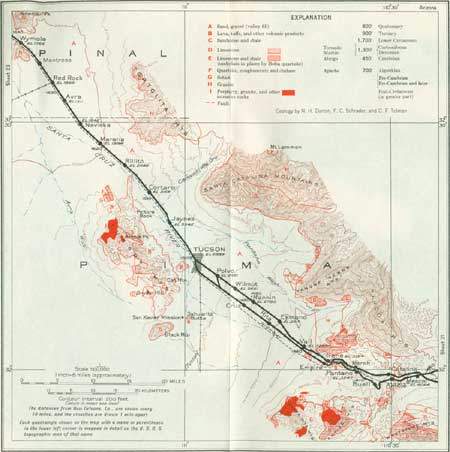

SHEET No. 22 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

TUCSON TO PICACHO, ARIZ.

|

Tucson. Elevation 2,389 feet. Population 32,506. New Orleans 1,499 miles. |

Tucson, the second city in size in Arizona, is the oldest settlement in the State and can boast of a colorful history. For many years it was a small, rough frontier town, preponderantly Mexican in population and appearance. Now it is a well-ordered city containing the State University, with an enrollment of more than 3,000 students, many high-class hotels, clubs, and a large residential district of particular beauty and charm. These features, in addition to the mild, healthful climate, attract many new residents, as well as tourists.

The State University, which is now accredited by the American Association of Universities, was built on ground donated by three leading gamblers of the city, and the first building was constructed before there was a high school in the Territory; during its first years students had to be taught the prerequisites to its freshman course. The university includes the Arizona Bureau of Mines, which is making investigations of the mineral resources of the State, and the Stewart Observatory for astronomical research. An important investigation conducted by Prof. A. E. Douglas has established a chronology of tree rings, which gives a key to the age of logs used in aboriginal houses and even to some that occur in petrified condition. There are at Tucson also the Desert Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution and a seismologic observatory of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey.

According to long observations by the United States Weather Bureau the average annual precipitation at Tucson is 11.8 inches, usually with the maximum rainfall in July. The precipitation shows wide variation, however, sometimes falling considerably below 10 inches (5.26 inches in 1885) and occasionally exceeding 15 inches (24 inches in 1905). The mean annual temperature is 67.3, and the humidity is generally considerably under 50 per cent. The daily range in temperature ordinarily varies from 32° to 57°. The average number of sunshiny days in the year is 309. Snow is rare in the valley but often falls heavily on the surrounding high mountains.

Tucson is built on the nearly level desert on the east bank of the Santa Cruz River, a wide watercourse which is dry most of the time. In every direction are fine views of the splendid mountains that encompass the far-reaching desert flat. To the north is the high Santa Catalina Range, which rises more than a mile above the slopes at its base; its highest summit, Mount Lemmon (elevation 9,150 feet), is in plain sight. This range is continued far to the east in the Tanque Verde and Rincon Mountains. To the south are the Santa Rita Mountains and the Sierrita Range, separated by the valley of the Santa Cruz River, and to the west and northwest are the pinnacled Tucson Mountains, not high but very rugged. Beyond the Sierrita Mountains is a distant view of the prominent Baboquivari Peak (bah-bo-kee-vah'ree).

There was considerable mining in the general region about Tucson by Spaniards, Mexicans, and Americans down to 1861, when all industry ceased. It was revived in 1878 with the discovery of rich ores at Tombstone. Several productive mines are now in operation in the Empire, Santa Rita, and Sierrita Mountains. In the Twin Buttes, on the east side of the Sierrita Mountains, there are mines producing ores of silver, copper, and lead.

The Santa Cruz River rises in Mexico south of Nogales, and on the rare occasions when it carries a large flood it empties into the Gila River southwest of Phoenix; its total length is thus about 200 miles. With the advent of the missionary-explorers, in the early days, its valley became an important artery of travel from the western part of Mexico to Arizona and the north and west. The first of these explorers of whom there is authentic record was the heroic German Jesuit Eusebio Francisco Kino, who spent 20 years in constant journeying, often entirely alone, throughout the Indian region as far west as the Colorado River. He left Mexico City in 1687 and, after founding several missions in northern Mexico, reached the Indian rancherías of Guevavi and Bac, on the Santa Cruz River, in 1691. In the next few years he reached the coast of the Gulf of California and also discovered Casa Grande, on the Gila River. He visited Mexico City in 1695. In 1696 he reached Quiburi (kee-boo'ree), the Indian settlement on the San Pedro River. He visited this place again in 1697 and followed the San Pedro and the Gila to and beyond Casa Grande. He returned by Bac,37 9 miles south of Tucson, where he laid the foundation of the church of San Xavier in 1700. At that time Bac had a population of 830, with 176 houses, extensive wheat fields, and much well-tended livestock; it was the largest ranchería in the Pima country.

37Bac, a Pima word frequently encountered, means house, adobe house, or a ruined house.

In 1700 also Kino descended the Gila River to its mouth, and in 1701 he returned to the vicinity of Yuma and crossed the Colorado River on a raft. The observations made on these explorations convinced him that California was not an island. In 1702 he made another journey to the mouth of the Colorado and other places. He continued his travels for a few years more, taking his last view of the Gulf of California in 1706. He died at Misión Dolores in Mexico in 1710 or 1711, at the age of about 70 years. In some of these great journeys he was alone; in others he was accompanied by Father Juan María Salvatierra and Capt. Juan Mateo Mange. At that time there were no other Spaniards in the Southwest, so that these journeys were lonesome and hazardous, but Kino found the Indians perfectly friendly and eager to learn, and they gave him guidance and supplies. His persistence and endurance were phenomenal.

A mission was conducted at Bac by the Jesuits from 1701 to 1767, when that order was expelled by the Spanish Government and the Franciscans placed in charge of all missions. One of the Franciscan missionaries located in San Xavier was Padre Francisco Garcés, the great explorer whose journeys down the Santa Cruz Valley and over a wide region as far as Utah and California during a period of 13 years constitute one of the most brilliant chapters of American history. Born in Spain in 1738, he was 30 when he entered upon his heroic career as missionary to the Indians of Pimería Alta. His first "entrada," in 1768,38 was from Bac to the Gila River, and later he proceeded down that stream to its mouth and crossed the Colorado, finally reaching the Mission San Gabriel in California. In 1775 he accompanied Captain Juan Bautista de Anza's expedition to found San Francisco as far as the Colorado River and then made a great trip alone, circling to the north and returning to Bac by a route that gave him a glimpse of the Grand Canyon, being thus the first white man to approach that great spectacle from the west. He gave it the name Puerto de Bucareli. In 1779 he established his ill-fated colony in the Yuma region and was massacred with it on July 19, 1781. He is now buried in San Pedro de Tubutama, in Sonora. A coworker, Padre Pedro Font, has written of him: "He is so fit to get along with the Indians and go about among them that he seems just like an Indian himself. In fine, God has created him, I am sure, totally on purpose to hunt up these unhappy, ignorant; and boorish people."

38Garcés' travels have been described in detail by Coues (Diary and Itinerary of Francisco Garcés, 1775-1776, 2 vols., Harper, 1900).

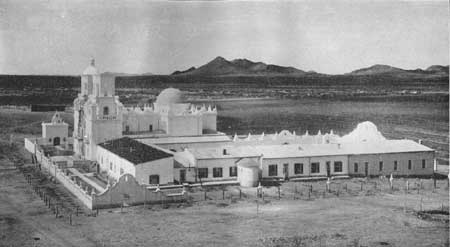

The present beautiful and interesting church of San Xavier at Bac, shown in Plate 21, was rebuilt very near the site of the first church, which was destroyed in the Indian outbreak of 1751. It was begun probably in 1783 and finished in 1797 (the date carved on the sanctuary door), during the period of comparative peace and prosperity that extended from 1786 end of the Spanish rule in 1822. The church is still in use, together with a school for the Indian children of the neighborhood.

|

| PLATE 21.—THE OLD MISSION OF SAN XAVIER DE BAC. Ten miles south of Tucson, Ariz. |

In the immediate vicinity of the present Tucson there were several early Indian villages which doubtless were passed by Father Kino in his journey to Casa Grande in November, 1694. The first Spanish settlement in the immediate neighborhood appears to have been San Agustín de Tucson, located on a low ridge 3 miles northwest of the present city hall, some time prior to 1763. It led a precarious and intermittent existence owing to Apache depredations, as did also the small Indian village of "San Cosine de Tucson,"39 which sprawled at the foot of Pinnacle Peak, now familiarly known as "A" Mountain, from the great white initial annually inscribed upon it by university students. Here under the guidance of Padre Garcés an hacienda and small settlement were established in 1776; this was known as El Rancho de Tucson and later as El Rancho del Padre. Half a mile northwest a mission was built under the name San Jose de Tucson. About this time the Spanish garrison was transferred from Tubac, 44 miles away, to San Agustín de Tucson and later to the present site of Tucson. Around the presidio at Tucson was built an adobe wall 12 feet high with low towers and parapets, one corner of which is marked by a bronze tablet. This diminutive walled city became the metropolis of the Southwest and for a long time marked our extreme western frontier. The valley was richly productive, mining was successful, and the hills were covered with herds of wild cattle. On the withdrawal of soldiers and missionaries from southern Arizona before and after the war of Mexican independence, the Apaches resumed their depredations, killing many persons and destroying 100 houses and several settlements. At this time from 3,000 to 4,000 settlers left the country, only a few remaining at Tucson. It is stated by Lockwood that in 1848 the population of Tucson was 760 and Tubac 249 and that Tubac was abandoned at the end of that year.

39The name Tucson means "the foot of a black hill," from the Papago Indian words tjuik, meaning black, and son, meaning foot of, or "the place dark springs," from the Sobaipuri name "Stookzonac." (Lockwood.)

Even under American rule it was not until after the Civil War that Apache and other warring Indians were finally conquered and banished to reservations. Fort Lowell, the old United States Army post, of which the ruins still stand 7 miles northeast of Tucson, was established in 1862, abandoned in 1864, reoccupied in 1865, and moved in 1873. It was named for Gen. C. R. Lowell, of the United States Cavalry. After the Gadsden Purchase Americans began to arrive, not a few being encouraged to journey thither by sheriffs and vigilance committees of neighboring States. With these came sturdier citizens with true pioneer spirit, but no white woman resided permanently in Tucson until 1870.

On the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 Tucson was seized by Confederate troops from Texas, who in turn withdrew on the approach of the Union volunteers from California (the "California Column") under Colonel Tarleton. (See p. 154.)

The stage from San Antonio to San Diego began making two trips a month late in 1857. For a while it passed through Tucson, but later it followed a more northern route in the Gila Valley. Tucson was on the oldest highway from the Rio Grande to Yuma and the Pacific coast, and traders and Government wagons with supplies for the various army posts in the Apache country were constantly on the move. The railroad arrived in 1880, and this fact was heralded to the world by telegrams from the proud citizens to the President at Washington and the Pope at Rome.

Near Tucson there is a small settlement of Papago (pah'-pa-go) Indians (527 in 1932) at the mission of San Xavier at Bac, and there are also two small settlements of Yaqui Indians from Mexico on the western and southern margins of the city.

The Indians now known as Papagos live mostly in a large reservation in the desert southwest of Tucson (4,914); on the Gila Bend Reservation, west of Phoenix (224); and in the Chiu-Chiuschu Reservation, south of Casa Grande (349). The Indians of this region claim descent from the builders of Casa Grande (see p. 197), and they are a branch of the Piman family. The "Pimas" lived in the Gila and Salt River Valleys, the Papagos in the Santa Cruz Valley and west into Sonora, Mexico. Another Piman tribe, the Sobaipuri, now extinct, occupied the San Pedro and Santa Cruz Valleys during Kino's time, when it was estimated that the total Pima population was about 12,000. The Papagos ("bean people") are a large-framed, well-formed people of dark skin and rather bold, heavy features. The women are of more delicate mold than the men, and some of them are decidedly handsome. The bravery of the Papagos has been proved in many conflicts with the Apache and other predatory Indians, and they have been uniformly friendly to the whites. Many of them are industrious and good workmen. Their life is closely adjusted to the arid region in which they live, especially in the matter of water supply for themselves, the use of flood waters for irrigation, and the utilization of the scanty natural food resources. They often have had to move to places favorable to their interests, and at times starvation has taken many lives. Mesquite beans and the fruit of the sahuaro, pitahaya, and agave, besides acorns and camote, an edible root, are important food resources, especially in poor seasons; formerly there was considerable game. One of their principal trading commodities is salt, which they gather from lagoons on the shore of the Gulf of California. The Papagos are divided into clans, two of which are included in the "red velvet ants," who are regarded as the original owners of the country, and the others in the "white velvet ants," who have come later. Descent in these clans is by the male line, which is contrary to the custom of the Pueblo Indians. The Papagos of San Xavier apparently absorbed the Sobaipuris, the last of whom, Encarnación Mamaxe, died at San Xavier Mission early in 1932, at the age of 106 years. The Papagos regarded the sun as the "Father," and their principal deities were the "Elder Brother" and the "Earth Magician," but most of them are now Catholics.

The Desert Laboratory occupies 860 acres on the Tumamoc Hills in the western part of Tucson. It was established in 1903 with the belief that this location offered the greatest opportunities for studying desert vegetation and the problems of its growth, its enemies, and soil relations. In 1905 it was made the headquarters of the department of botanical research of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. It has obtained a large amount of most valuable information regarding plant growth, soils, and water conditions in the desert. The State Agricultural Experiment Station at the university has branches in various parts of Arizona, studying many problems of crop, fruit, cotton, and nut production.

Tucson obtains its water supply from wells that draw from the underflow of the Santa Cruz Valley south of the city. In the Rillito Valley (ree-yee'toe), just north of Tucson, underground water is pumped for irrigation. When old Fort Lowell was located in this valley, at the mouth of Pantano Wash, the cavalry horses were fed with hay cut from the flood plain, which is now dry and deeply trenched.

From Tucson a branch line of the Southern Pacific system ascends the Santa Cruz Valley to Nogales, on the international boundary, and thence goes to Guaymas (10 hours), Guadalajara (48 hours), and Mexico City (65 hours). At 44 miles south of Tucson it passes the ruins of the old Spanish presidio of Tubac, which dates prior to 1752 and was erected to protect the neighboring missions. At this place in 1858 to 1860 a small group of Americans and Mexicans partly restored the ruins and published the "Weekly Arizonian," the first newspaper in the Territory. A short distance beyond Tubac is the old Tumacacori Mission (too-ma-ca' co-ree), established by Father Kino in 1702, now a most interesting national monument under Government protection.

Westward from Tucson the railroad crosses the southwestern portion of Arizona, a region presenting geologic and topographic features such as characterize the Basin and Range province of the Southwest. While the geology has not been mapped in detail, the principal features have been ascertained by reconnaissances by Bryan, Ross, Wilson, Lausen, Darton, and others. Many of the ridges consist of the pre-Cambrian granites and schists of a "basal complex." In places these are overlain by sandstone of Cambrian age, limestones of Devonian and Carboniferous age, sandstone and shale of Cretaceous age, conglomerate, lavas, and sands of Tertiary age, and thick beds of Quaternary sand and gravel. Igneous rocks of various ages cut the schists and sedimentary rocks, and some of the younger granitic rocks are not very different from the pre-Cambrian granites. The sea covered much of the area for at least a part of Carboniferous time, for there are remnants of limestones of this age at many places. Outliers of Apache rocks indicate that there was deposition of sediments in the region during part of Algonkian time, the products of which may have been much more widespread than is indicated by the small remnants that are exposed. The features most striking to the traveler are mountains or knobs of schist or granite and ridges and mesas made up of a thick succession of lavas and other volcanic rocks. Many of the knobs rising above the valley floor are the summits of ranges which are now nearly buried under the thick valley fill of sand and gravel washed from the mountain slopes for a million years or more. Before the extrusion of the Tertiary volcanic matter the region presented an irregularly eroded surface, doubtless a desert, some areas of which were occupied by sands and boulder deposits of earlier Tertiary age. These deposits consisted largely of detritus from ridges and were mostly laid down by torrential streams under conditions similar to those of the present time. The lavas came to the surface through craters and cracks at various places and spread widely, probably filling broad valleys and desert flats. Doubtless some of the earlier ridges were not entirely buried. At intervals a great amount of ash, tuff, and other fragmental material was blown out of some of the vents. The succession of sheets of lavas and fragmental material is 2,000 feet or more thick in some areas, but it varies considerably from place to place in thickness and in the character and order of its rocks. The lavas were later uplifted, tilted, flexed and faulted, and widely removed by erosion, so that their original extent is not evident. Much of their detritus, together with that of older formations, makes up the thick alluvial fill of the present valleys.

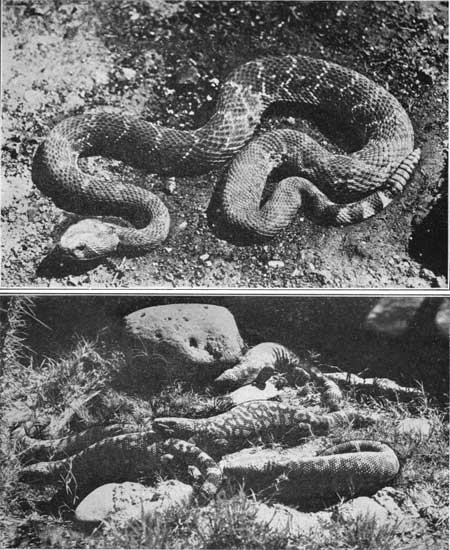

The great deserts of the Southwest at first sight seem nearly destitute of animal life, but actually they are the habitat of many animals in considerable variety, most of them, however, small and not often in sight. Most numerous perhaps are the kangaroo rats, which live in large colonies in the sandy areas, but they are nocturnal, and most of their associates have the same habit. Coyotes, foxes, and bobcats frequent many localities. Various lizards and the bold little horn toad (Phrynsoma platyrhinos) are abundant, and in places there are rattlesnakes (see pl. 23, A), including the variety known as the "sidewinder" (Crotalus cerastes), a name referring to his sidelong motion both in locomotion and attack. The rare tiger rattler lives in the rocks in out-of-the-way places, and the Sonoran coral snake (Elaps euryxanthus) is occasionally found. The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) (see pl. 23, B), a clumsy black and pink lizard a foot or more in lengthy is of frequent occurrence in southwestern Arizona from the San Pedro River to the Colorado. He carries poison about the teeth in his lower jaw, and his bite is fatal to small animals. The larger lizard known as chuckwalla (Sauromalus ater) occurs near the Colorado River, and the Indians find him as palatable as chicken. Jack rabbits and cottontail rabbits are plentiful, especially in the vicinity of the arroyos, and there remain a few of the rare antelope jack rabbits, a taller, more slender species than the common one. A few antelopes, deer, wild sheep, and lions remain in the mountains; formerly these animals were abundant, especially the antelope, but vigorous hunting has greatly reduced their number. The tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) roams over some of the desert areas, and his empty shell is a common sight. The average size is 8 to 10 inches. These tortoises are usually found far from water holes and evidently are not dependent on water. This is true also of the other desert animals, which obtain from plants the small amount of water that they need. Experiments made with desert mice appeared to prove that they will not drink water at all. Quail are abundant in most seasons, and doves thrive in the irrigated areas and near water holes. Cranes and similar birds are found along the rivers, and crows and buzzards congregate rapidly when food is in sight. The road runner (Eolaptes chrysoides mearnsi) is frequently seen. It eats rats, birds' eggs, and snakes. It runs very fast and stops quickly, using the long tail as a brake. Tarantulas (large hairy spiders), centipedes, and scorpions occur in many places; though their bites or stings are painful and probably somewhat poisonous, they appear not to be fatal.

|

|

PLATE 23.—A (top), RATTLESNAKE. Common throughout

western Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. B (bottom), GILA MONSTERS. Found in many places in southwestern Arizona. |

The Tucson Mountains, west of Tucson, are the Frente Negra, or Black Face Mountains, of Garcés. The range is of moderate height and consists mostly of volcanic rocks in widely extended sheets and several stocks, erupted from craters or possibly from some cracklike vents in early Tertiary time.40 On the east slope of the mountains is an old quarry in light-colored volcanic tuff which has been used for building one of the university buildings and many houses in Tucson.

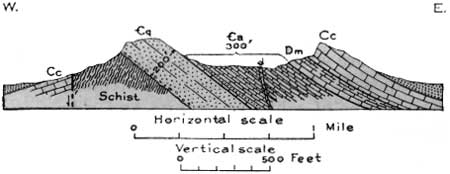

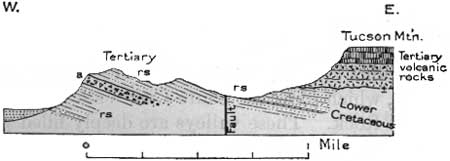

40Rhyolites and andesites, in part porphyritic, are the principal rocks, with some tuff and basalt. Amole Peak (ah-mo'lay), the highest summit, and some other knobs consist of intrusive rhyolite. Granite and granodiorite, apparently intrusive, occur on the west side of the north end of the range. Picacho de la Calera, an outlying butte to the northwest, consists of limestones of Carboniferous and Devonian age (Escabrosa and Martin) with abundant fossils. These limestones are underlain by 300 feet of typical Abrigo limestone with trilobites and other fossils of Upper Cambrian age, and at the base, lying on pre-Cambrian schist, is 200 feet of Bolsa quartzite. The section in Figure 48 shows the relations at this place. Along the foot of the southwest side of the Tucson Mountains are extensive exposures of sandstone and shale believed to be of Lower Cretaceous age. They lie nearly level and are overlain by the Tertiary volcanic succession to the east and by a sheet of rhyolite to the west. Farther north they are faulted against a thick body of red sandy shale and arkosic sandstone with an included bed of agglomerate with much volcanic material of Tertiary age. Figure 49 shows the relations in this part of the area.

FIGURE 48.—Section at Picacho de la Calera, 16 miles northwest of Tucson, Ariz. €q, Cambrian quartzite; €a, Abrigo limestone; Dm, Martin limestone; Cc, Carboniferous limestone; d, dike

FIGURE 49.—Section of the west aide of the Tucson Mountains, Ariz., about 3 miles south of the Ajo road, or 2 miles south of Amole Peak. a, Agglomerate; rs, red sandy shale

The Tumamoc Hills, an outlying knoll of the Tucson Mountains just west of the city, consist of a succession of lava flows (andesite, rhyolite, tuff, and basalt) and several intrusive masses that are probably of Pleistocene age.

|

Cortaro. Elevation 2,156 feet. Population 80.* New Orleans 1,511 miles. |

From Tucson the railroad follows the wide flat adjoining the Santa Cruz River, which has a sandy bed of many braided channels, usually dry. At times of rain the Santa Cruz carries considerable water. According to records of the United States Geological Survey the flow at Tucson aggregated 57,200 acre-feet in 1914 and 24,700 acre-feet in 1915. The Santa Cruz is an affluent of the Gila, which its channel reaches in the neighborhood of Phoenix, but even in Garcés' time it sank into the sands near Picacho Peak, and at present it rarely flows even that far. However, there is considerable underflow in the sand and gravel of the valley fill, especially below the mouths of Rillito Creek and Cañada, del Oro, and this water is pumped for irrigation. The irrigated area, is entered near Jaynes, a short distance out of Tucson, where there is a State experimental farm; it continues with some interruptions nearly to Naviska. The area under cultivation is about 7,000 acres. The water is supplied by many shallow wells operated by electric power from Tucson, and there are some flowing wells. The water is carried by canals, mostly cement lined. Much cotton and alfalfa are raised, together with various other crops. Cotton is a native plant (Cabeza de Vaca was presented with cotton garments by the natives in 1535), but the wild variety gives only a small yield of the fiber. The cultivated cotton yields about a bale to the acre. The average crop in the valley requires from 20 to 24 inches of water, but alfalfa, which is cut five or six times a year, requires 36 inches. There is considerable dairying to supply milk for Tucson and other places.

|

Tortolita. Elevation 2,069 feet. Population 32.* New Orleans 1,516 miles. |

Northeast of Rillito is a conspicuous range of buttes and ridges known as the Tortolita Mountains (tore-toe-lee'ta). They consist of pre-Cambrian granite and schist and rise abruptly from long slopes of gravel, sand, and other detritus. On the south edge of the range are volcanic rocks. To the south and southwest from the railroad near Naviska siding there are fine views of the rugged ridges of the Roskruge, Coyote, Quinlan, and Baboquivari Mountains, the last culminating in the square tower of Baboquivari Peak (elevation 7,740 feet), 50 miles away. To the west are the Silver Bell Mountains. These are all on the west side of the wide desert of Avra Valley, which joins the Santa Cruz Valley a short distance southwest of Red Rock. These valleys are deeply filled with gravel and sand.

From Tucson to Picacho the railroad follows the route pursued by Padre Garcés and the expedition of Captain Anza in 1775 on their long overland journey to establish a colony at San Francisco. They traveled, however, on the left bank of the stream as far as Red Rock. According to Padres Garcés and Font, the Anza expedition consisted of 30 soldiers and 136 other persons, including women and children. It followed the Santa Cruz River through Bac and Tucson. Rillito lies at the place they called Llano del Azotado (meadow of the flogged man), because a deserting muleteer taken into custody was here given 12 lashes. Passing near the present Red Rock station to a point beyond Picacho Peak, it turned to a more northerly course, approaching the Gila River about 2 miles west of Casa Grande, which the friars visited and minutely described. Several camps were made on the Gila River in this very populous Indian country, where wheat, Indian corn, and cotton were being raised. The course then swung southwestward around the south end of the Sierra Estrella across the "Dry Wash" (apparently Waterman's Wash) and through the pass in Maricopa Mountains now followed by the railroad to modern Gila Bend, a route which later became the emigrant trail. Near Gila Bend they found an Indian village, called by Padre Garcés the Pueblo de los Santos Apostóles San Simón y Judas.

|

Marana. Elevation 1,994 feet. Population 75.* New Orleans 1,520 miles. Red Rock. Elevation 1,868 feet. Population 40.* New Orleans 1,531 miles. |

Rillito and Marana are small settlements sustained by irrigation water pumped from the underflow of the Santa Cruz River. West from Naviska siding the region is a wide desert. Occasional sahuaros are in sight from Avra siding and westward nearly to Picacho. The village of Red Rock is on this wide desert plain, which extends north to and beyond Phoenix and far to the west. This plain is floored with sand and gravel, in most places very deep, and the subsurface geology is not known. The embankments at intervals along the railroad in this vicinity were built for protection from flood waters. Many steep-sided mountains rise out of this plain, mostly of granite, schist, or volcanic rocks, their rugged outlines indicating rapid disintegration.41 The valley floor bears a sparse vegetation of small mesquites and other plants, widely spaced on account of the arid climate.

41Rock disintegration proceeds rapidly in the desert regions of the Southwest. The great difference of temperature between hot afternoons and chilly dawns is an important agent, causing expansion and contraction, and frosts of midwinter are potent in aiding disintegration. Leaching of limestones and decomposition of minerals in crystalline rocks are factors which produce large results in a few centuries. Most rocks are traversed by joints or cracks, and along these disintegration progresses. It finally isolates spalls or blocks of the rock, and these fall and eventually crumble into detritus, which is worked down the slopes and becomes valley fill or is carried by freshets into and along the larger streams. Running water containing sediment in suspension is a powerful erosive agent, and wind-blown sand is especially effective in removing decomposed or soft rock.

Joints in rocks are cracks, generally not of great length, due to shrinkage in cooling if the rocks are of igneous origin, or to strains of various kinds, especially earth movements. They may run in various directions or may be arranged in sets of nearly parallel cracks which intersect other sets at approximately constant angles. Joints differ from faults in being much smaller fractures that show little or no slipping or vertical displacement of the rock along the break.

A railroad branches to the southwest from Red Rock to Silver Bell, 18 miles distant, a small town with a large copper mine. The workings are in a group of high ridges, consisting in part of rhyolite and tuff of volcanic origin, and a succession of 3,700 feet of quartzite and limestone, the latter containing Carboniferous fossils (C. F. Tolman). An extensive intrusion of alaskite porphyry carries blocks of the limestone, one of which, according to Stewart, is nearly 2 miles long and 2,000 feet wide, and there are later dikes of andesite and trachyte porphyry. The ore reduction works at Sasco are visible from Red Rock. The Waterman Mountains, a small range 6 miles southeast of Silver Bell, consist of porphyry, quartzite, and a limestone that contains fossils of Permian age (Naco limestone).

|

|

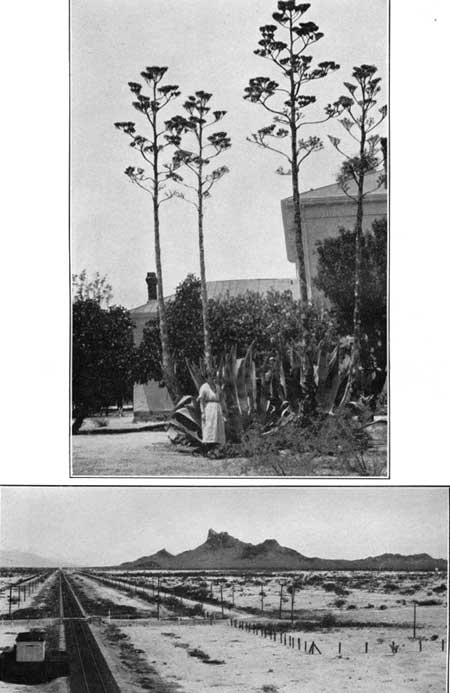

PLATE 22.—A (top), MAGUEY (AGAVE PARRYI). Abundant on

many limestone hills in the Southwest. About 7 years is required for development,

after which it dies. Allied species are the source of the Mexican drinks mescal

and pulque. B (bottom), PICACHO, A NOTABLE LANDMARK NEAR WYMOLA, ARIZ. A mass of volcanic rock of Tertiary age. Looking southeast. |

Northwest of Red Rock, on the left side of the railroad, is the prominent peak known as Picacho or Saddlerock Picacho (see pl. 22, B), which becomes conspicuous near Avra siding and is a landmark for many miles in all directions. Its elevation is 3,374 feet. It consists of lavas steeply tilted to the north, and it may also include the neck or vent of an old volcano. The railroad passes very near this peak at Montrose and Wymola sidings. According to Garcés, it was called Cerro de Tacca by the Indians. Near it, in ancient days, was a Pima settlement or ranchería called Akutchiny ("mouth of the creek"), located at the sink of the Santa Cruz River.

|

Wymola. Elevation 1,766 feet. New Orleans 1,538-1/2 miles. |

In the pass a few rods east of Wymola siding there is a 10-foot monument just south of the tracks with the inscription "Lieut. J. Barrett and Privates G. Johnson and W. S. Leonard, killed April 15, 1862, in the only battle of the Civil War in Arizona. Erected by the Arizona Historical Society and Southern Pacific Railway, April 15, 1928." These men and a few others, members of the California Volunteers, had an encounter with Confederates who had just evacuated Tucson.

The Picacho Mountains, a high rocky range rising out of the desert plain north of Wymola, culminate in Newman Peak (elevation 4,529 feet). They consist of schist, all of which in this general region is believed to be of pre-Cambrian age.

Beginning near Wymola and extending for about 5 miles west is a very fine assemblage of cacti, growing mostly on the rocky slopes along the south side of the railroad. There are many stately sahuaros, barrel cactus (biznaga), cholla (cho'ya), and other desert species.

The region extending west from the San Pedro River to the Colorado River and the Gulf of California, constituting the northern part of the Province of Sonora, was known to the early explorers as Pimeria Alta (pe-may-ree'ah). When the Spaniards found that its northern and northwestern extension was occupied by the Papago Indians they called this portion Papaguería (pa-pa-gay-ree'ah), to distinguish it from the region of the more sedentary Sobaipuris of the Santa Cruz and San Pedro Valleys. With a mean annual rainfall on the lower lands ranging from 3 to 10 inches and a mean annual temperature of 67° at Tucson and 72° at Yuma, it is one of the warmest and most arid portions of the United States. In places the summer maximum temperatures are as high as 126°. The vegetation is a striking assemblage of peculiar plants in which large cacti, small desert trees, and many shrubs are present, but all widely spaced. No part of the region is so dry as to be without plants except a few areas of drifting sand. Where the ground water is near the surface, as in the wider plains subject to occasional flooding by rains, there is considerable mesquite, but this plant also grows in many places where the amount of water is very slight for most parts of the year. Mesquite, like a few other desert plants, has a very long tap root that penetrates to sands containing some moisture, and also a system of wide-spreading lateral roots that quickly absorb water near the surface when there is rainfall. Creosote bush, iron wood, paloverde, ocotillo, grasses, and scattered cacti of several kinds are the more noticeable plants in the valleys and along the dry mountain slopes.

The topography is of the Basin and Range type, with high, bare rocky ridges, mostly narrow, separated by wide, flat valleys. The larger features trend north and south, although there are many local exceptions to this trend. The valleys range from about 3,000 feet above sea level in the northeast to 250 feet in the Yuma Desert. The mountains are bare and desolate, and the broad desert valleys with terrifying scarcity of water seem formidable to travelers. For many persons, however, the region possesses an intense interest and charm—often referred to as the lure of the desert.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec22a.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007