|

FORT VANCOUVER

The Administrative History of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site |

|

Chapter One:

OVERVIEW

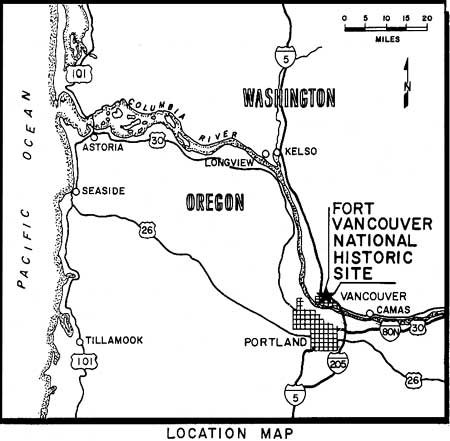

Fort Vancouver National Historic Site has special problems as well as special advantages. Located off of Interstate 5 in Vancouver, Washington, on the north shore of the Columbia River across from Portland, Oregon, Fort Vancouver is an open 208-acre park in the midst of an otherwise urban setting. Though Mt. Hood, to the east, and the nearby Columbia River are reminiscent of the area's older natural setting, two major highways border the site on the west and south. Light industry, a small airport that extends onto Park Service property, and Portland International Airport across the river also remind visitors that the slow pace of the 19th century has been left far behind.

|

| Location Map |

Ironically, this busy urban environment can be attributed directly to the influence of the Hudson's Bay Company's trading post. Between 1825 and 1845, Fort Vancouver served as an important center for the Northwest fur trade. But the site's significance goes beyond the fur trade; Fort Vancouver was also at the western terminus for American settlers traveling the Oregon Trail, thus a symbol for the expansion of national boundaries to the far western frontier of the Pacific Ocean. Many historians have called Fort Vancouver the "cradle of civilization" in the Northwest, both because the Hudson's Bay Company constructed one of the earliest schools in the area and because the fort was a way station or point of departure for missionaries proselytizing among native peoples already settled in what later became the Oregon Territory. Perhaps more importantly, Fort Vancouver's Chief Factor John McLoughlin facilitated agricultural development in the Northwest; European seed stock and fruit trees given to the American settlers helped new gardens and orchards blossom throughout the region.

Though Fort Vancouver was eventually abandoned by the Hudson's Bay Company, the significance of its activities and enterprise lingered in the collective memories of the local people, many of whom were descendants of retired Hudson's Bay Company employees. For years local and state groups fought for legislation to authorize a national monument which would recognize the site as an economic, cultural, and military center of early Pacific Northwest development. [1]

Though everyone could agree that Fort Vancouver should be cherished as a national symbol, not everybody agreed on what form that symbol should take. Indeed, the Park Service could not always agree on appropriate goals for development at Fort Vancouver. When the monument was authorized in 1948, the enabling legislation referenced the 1916 act which established the National Park Service. These acts contained two basic, and seemingly contradictory, directives for Park Service policy: first, the park site must be preserved and second, the public must have use and enjoyment of the site. [2] At Fort Vancouver these policies raised several questions: What was there to preserve? And how could the monument be developed to provide for public use and enjoyment? The answers were never easy or obvious. Without any remaining historic structures or features above ground, the Park Service faced an interpretive puzzle. They had to decide if preserving an empty open space or an on-going archaeological excavation would provide the best use of public space. At Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, the Park Service often found the best management strategy to be compromise.

Today, the prominent attraction at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site is the reconstructed Hudson's Bay Company stockade, including many of the buildings inside the fort: the bakehouse, blacksmith shop, Indian Trade Shop, and the Chief Factor's House where Dr. John McLoughlin once governed the fort. All of these reconstructed buildings are on the List of Classified Structures and the entire site is on the National Register. On a gentle rise overlooking the reconstructed fort is a MISSION 66-style Visitor Center which houses Fort Vancouver NHS' museum and visitor services. The old Vancouver Barracks parade ground provides open space on the northern half of the park for visitors, who also enjoy an uninterrupted view of the fort stockade from the Visitor Center. The Park Service property also includes the site of the historic Kanaka Village, west of the stockade, where most of the Hudson's Bay Company employees at Fort Vancouver once lived. Though nothing of the village, pond, and salmon house, remains above ground, Park Service plans have always included the restoration of a portion of this landscape for interpretation, based on historic and archaeological evidence. Other features of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site include the western half of Pearson Airpark and approximately three-quarters of a mile of Columbia River waterfront, which is separated from the stockade area by SR 14, a frontage road, and the airfield runway.

Though reconstruction and further land acquisition are currently the focus of Fort Vancouver's planning program, they were not always Park Service policy nor the obvious outcome of management decisions at Fort Vancouver. In the 1950s, the Park Service was reluctant to reconstruct at any historic site. Instead, it emphasized restoration of surviving structures or preservation of the integrity of a site. Fort Vancouver National Monument, as it was then designated, benefited from this policy in the late 1940s and 1950s, since the monument's most important cultural resources were the archaeological excavations and the curation of artifacts they uncovered. With Park Service funding, Archaeologist Louis Caywood and Historian John Hussey were able to document thoroughly Fort Vancouver's cultural resources and history up to that time.

Under Park Service policy, the general criteria for reconstruction at a park included the disappearance of the structures which are essential to public understanding and enjoyment, the existence of sufficient historical, archaeological, and architectural data to permit accurate reproduction, and the ability to locate the reconstructed structures on the original site. [3] Fort Vancouver seemed to fit these criteria perfectly. Not only did Louis Caywood locate the original site of the 1840s fort, but together, Caywood and Hussey's labors provided a strong basis for accurate interpretation and structural replication at Fort Vancouver. In addition, community groups continued to demand reconstruction of the Hudson's Bay Company post so they might celebrate the region's past as well as provide tourist dollars for the region's future.

However, the Park Service remained reluctant to reconstruct the fort in the 1950s. Their reticence to embark on a reconstruction was reinforced by two factors: lack of funding and the existence of an avigation easement over the fort site, held by the City of Vancouver, that prohibited any activities or construction that would interfere with the operation of Pearson Airpark. It would take the election of Julia Butler Hansen to Congress in 1960, to overcome these two obstacles. As the representative for Washington State's Third District, she took a personal interest in the monument and, within a year of her election, sponsored legislation that both enlarged the boundaries of the park and changed its designation to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. Throughout her career, Julia Butler Hansen supported the site with funding for specific projects, including reconstruction. With her assistance, the avigation easement over the fort site was modified, allowing a portion of the stockade wall to be rebuilt in 1966. Subsequently, Representative Hansen, as chairman of the House Interior Appropriations Subcommittee, secured funding for reconstruction of the entire stockade and several buildings within.

Besides careful documentation and planning, the fort's reconstruction required the Park Service's cooperation and compromise with the fort's neighbors. Since Fort Vancouver's development plans depended on further land acquisition within the old Vancouver Barracks, the Park Service had to cooperate and coexist with other federal and local agencies whose properties surrounded the historic site, including the Army and the City of Vancouver, which owned Pearson Airpark. Indeed, land and land management has continued to be one of the primary issues in the administration of the Fort Vancouver site: who owns it; who administers it; who uses it and for what purpose; how it is sold or exchanged; and how the boundaries of use and ownership are defined. When it comes to the management of Waterfront Park, the operation of Pearson Airpark, or the recreational use of park grounds, the debates over these questions have been especially rancorous.

The compromises these issues have required have contributed to the identity crisis which has troubled Fort Vancouver since it was established. Yet, Fort Vancouver not only survives, but is continuing to move in directions that reaffirm the congressional mandate to preserve and interpret the Hudson's Bay Company and its role in Pacific Northwest history. For instance, the recently reconstructed fur store is not just a new interpretive venue; it will also serve as a cultural resource study center, which promises to draw scholars, researchers, and archaeologists to examine its collections and deliberate on the cultural importance of Fort Vancouver and the fur trade. The unexcavated portions of the site also represent a potentially rich archaeological source for further information concerning the activities of the Hudson's Bay Company. Finally, a cultural landscape report, currently under development, updates the site's master plan and underscores the long-standing commitment to interpreting Fort Vancouver's historical identity. Though Fort Vancouver is faced with dramatic changes if the Vancouver National Historical Reserve is initiated, the decisions the Park Service makes in the next five years will define Fort Vancouver's role and development for the foreseeable future.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 02-Feb-2000