|

FORT UNION

Historic Structure Report |

|

| PART I |

Chapter V:

THE ARSENAL (continued)

A Temporary Move. In June, 1862, when most of the troops at Fort Union occupied the second fort (star fort), Shoemaker's old friend General Canby transferred the "old Hospital building" (probably HS 140, possibly HS 126) at Fort Union to the ordnance department on a temporary basis. The building was to be used for storage of ordnance stores. [45]

Undoubtedly due to changes that occurred during 1862 and 1863, little correspondence appeared in the files concerning the ordnance depot during those years. Like all of the operations of Fort Union and its depots, it, too, was temporarily moved over to the earthworks. By 1864, however, Shoemaker was back at his buildings around the first fort and writing his superiors in Washington requesting that Fort Union Depot's name be formally changed to Union Arsenal to prevent confusion with the quartermaster and commissary depots located a mile and a quarter away from his ordnance depot. [46]

Shoemaker and Construction. M.S.K Shoemaker was an efficient bureaucrat who took great care in watching over his stores and in expediting working procedures of the army. In 1864, he wrote to department headquarters in Santa Fe and recommended that the post commander direct his troops to requisition six months supply of stores to be drawn at one time because the paperwork for the small requisitions had to be sent first to department command in Santa Fe and then to Washington for approval. [47] This was typical of his way of running operations.

He remained sensible about construction of the new arsenal. In his annual estimate for 1865, he only included enough building materials to repair his old storehouses and quarters from the first fort construction. Although he did plan on building a simple adobe storehouse in the spring of 1865 on the site of his present arsenal, he intended to wait to construct new good buildings for his arsenal when he could use the appropriation for it. The price of materials and labor had skyrocketed during the war, so Shoemaker did not feel that the work that needed to be done justified the expenditures. Also, he was concerned about the pulse of the territory. He wrote: ". . . if this neighborhood should be again invaded as it was by the Rebels in 1862, when we had to remove all the Ordnance to the Field Works, the Arsenal buildings however odd they might be, would be subject to abandonment & destruction." He intended to keep the extant buildings as serviceable as possible with as little cash outlay for their repair as possible to "protect the stores until after the country becomes settled and new buildings can be erected at a reasonable cost." [48]

On June 8, 1865, Shoemaker wrote to department headquarters in Santa Fe and requested that the adjutant general issue an order to have all ordnance and ordnance stores "not absolutely necessary for the use of the troops and posts in this military department sent in to this arsenal with proper invoices with as little delay as practicable." [49] Shoemaker based his request on General Orders 77, which called for reducing expenses and which his superior, the chief of ordnance in Washington, had brought to his attention. This must have caused some consternation, because other power plays ensued.

Carleton had requested that Shoemaker return to him all monies, expenditures, contracts and the like for Union Arsenal. In June of 1866, the chief of ordnance in Washington wrote to Carleton and enclosed a letter signed by General Grant reminding Carleton that "Disbursement of Ord. appropriats. are under exclusive control of the Chief of Ordnance, and no Dept. — or Dist. Commander should interfere with the same." [50]

By early 1866, Shoemaker was well into the study of appropriate building technology for the Fort Union vicinity. He wrote:

In reply to your inquiry as to whether the purpose of covering of earth on the upper floors of the buildings is necessary and why, I will state that, owing to the dryness of this climate, where no rain or snow falls for four or five months at a time, the roofs become so dry & shrink so much that the first rains, which fall very heavily about midsummer, are certain to run through. To a greater or lesser extent, the leakage is thus absorbed by the dry earth before it reaches the upper floor. This earth overhead also preserves the temperature of the rooms, and when the building is well constructed, it renders it almost fireproof. The roof and entire superstructures might burn off without a spark of fire getting below the upper floor, which itself is a second roof. Tin roofing may obviate the necessity of the earthen covering, but I see that it is the practice in the QM General Department at Fort Union Depot when they are building extensively to put heavy layers of concrete under their tin roofs. [51] it is no better & costs ten times as much as earth. If it is determined to cover the magazines with Tin and I do not advocate it, it will be necessary to send mechanics here that understand the business of putting it on. This will augment the expense of the buildings, and my experience here leads me to the conclusion that it is unnecessary. [52]

Ordnance Reservation. Although Shoemaker had been referring to his arsenal as an arsenal, the land was not officially assigned for it until 1866. General Orders No. 28 stated that "a portion of the Military Reservation at Fort Union, New Mexico to the extent of one mile in length and a half a mile in breadth is hereby set apart as a site for the Arsenal at that Fort. This portion of the public land is appropriated as an ordnance Reservation and will be laid off so as to include the site of the old Fort in mid center." [53]

The assignment of land for a separate ordnance depot angered the head of the quartermaster depot at Fort Union. In a letter to the quartermaster general in Washington, Fort Union's quartermaster criticized the fact that the ordnance reservation included the cemetery. Also, he expressed his concern that the new reservation could include some of the most important springs of water in the vicinity depending on who made the survey. He concluded in his remarks that all of the depot officers had shared equal rights and privileges up until that time, and that if any depot deserved a separate reservation, it was the quartermaster depot because of the large number of stock it had that were dependent on the reservation for grazing. [54]

Shoemaker permitted a small sutler's store to be established within the limits of his post. He justified its establishment saying that it was for the good of the service and that the other sutler's store was a mile away. [55] He also assured his superiors in Washington that he had nothing to do with the business of its operation. [56]

New Arsenal Construction. The formal assignment of land for the ordnance reservation allowed Shoemaker to pursue construction of his depot. In October, 1866, his detachment had completed the construction of two magazines for fixed ammunition (HS-109, HS-110). Also, his men had nearly completed the large storehouse (HS-103). The enclosing wall around the magazine compound was under construction, and only several hundred feet of it remained to be completed. Shoemaker explained that they had lost some adobes to rain, and then the weather became too cold to make them. [57]

The onset of winter did not slow down Shoemaker's pace. By January he had employed a local mason. Shoemaker hired him to construct cisterns (any or all of HS-117, HS-121-123). The workman had done some of the finest work of that type that he had seen in New Mexico. Although he was still waiting for approval to construct the cisterns, Shoemaker asked the chief of ordnance to arrange for six barrels of hydraulic cement to be shipped from Fort Leavenworth to Fort Union by the first wagon train. He believed that was enough cement for the cisterns he proposed to make: two cylinders 12 feet in diameter and 18 feet deep. He proposed constructing the ducts from the building to the cisterns of stone lined with cement. He intended to have the water pass through a charcoal filter. By using this method of construction, he would not need cast iron pipes. He estimated that the cisterns would each hold 15,000 gallons of water and would cost $500 each to construct. [58]

In May, 1867, Shoemaker was recommended to be appointed Colonel by brevet because of his loyalty to the Union during the Civil War. The justification for his breveting included a description of his accomplishments at the arsenal. The statement said that Shoemaker started with a small group of deteriorated log houses and, through economical expenditure, he constructed warehouses sufficient for all of the arms and ammunition under his care. Shoemaker carefully oversaw the construction of the adobe buildings, and Colonel A.J. Alexander, author of the recommendation, wrote that the adobe buildings were the best constructed that he had ever seen and that they were built at two-thirds the cost of the ones that the quartermaster depot constructed. Alexander went on to say that "The interior of the warehouses are models of neatness, the ventilation is perfect and the security against fire as great as can be effected with the materials." [59] Although the breveting did not come through, Shoemaker did increase his power when he was appointed chief ordnance officer of the District of New Mexico on September 1, 1867. [60]

Even as late as 1868, Shoemaker was still using the old buildings of the first fort. Rather than using his appropriated funds for completing the adobe walls that enclosed the compound, he wanted to build the arsenal barracks. He wanted his men to be more comfortable than they were in the old huts. When sending in his letter requesting permission to build the barracks, he noted that the plans for the barracks were authorized by the War Department in 1860, and that the plans for them were in the Ordnance Office in Washington. [61]

Apparently the barracks (HS-113) were constructed, for in future letters to the ordnance department in Washington, Shoemaker requested $10,000 for construction. He planned to use the money to complete the adobe walls around the complex and to build simple quarters for men with families. He wrote that the commanding officer's quarters were sufficient for the time being, and that his former estimates were too low. [62]

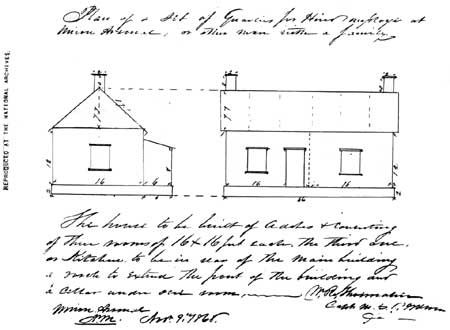

The following month, Shoemaker requested approval on a set of plans for quarters for hired personnel (figure 11). The single set of quarters was to consist of an adobe building with three rooms, each 16x16 feet. Additional aspects of the building included a kitchen to the rear, a porch across the front of the building, and a cellar under one room. In the letter that accompanied the drawings, Shoemaker wrote that his civilian employees lived in the "old log huts that were built in order to shelter the men about fifteen years ago. They stand in the way, and have become almost unlivable, requiring constant repairs." He went on to say that his plan included three sets of quarters, and he intended to complete those and the enclosing wall (HS-100) around the arsenal for $10,000 during 1869. [63]

|

| Figure 11. In November, 1868, Shoemaker submitted this plan of quarters for a hired employee to the ordnance office in Washington for approval. The caption under the drawing reads: "The house to be built of adobes & consisting of three rooms of 16x16 feet each. The third one, or kitchen, to be in rear of the main building a porch to extend the front of the building and a cellar under one room." |

In June 1869, Forts Lowell and Sumner, New Mexico, were abandoned and discontinued as military posts. All of the ordnance and ordnance stores from those forts were transferred to Fort Union Arsenal. [64] Apparently Shoemaker's physical plant was able to absorb all of the property transferred to him. The closing of these two forts, however, was indicative of changes occurring throughout the west.

In 1869, Fort Union Arsenal underwent an inspection for the office of the Inspector General. The inspection described the arsenal as follows:

Buildings: The storehouses and shops are of quality constructed of adobe and shingles of sufficient capacity and convenient in their arrangement. A part of them, including magazine enclosed by an adobe wall.

Quarters: The quarters for the Commanding Officer is an old log building of inferior quality and will soon be required to be replaced by a better building.

Cisterns: Cisterns are being constructed at this Arsenal. Water is supplied by water tanks and hauled from a spring some half mile distant.

Fire Engine: There is an old hand fire engine here which is of little or no account.

Improvements: The cost of the permanent improvement is estimated at $30,400. [65]

Shoemaker continued on with his construction. Appropriations sometimes lagged behind necessity, so he was writing to headquarters in Washington fairly frequently asking for approval to start spending his anticipated appropriation for construction—which usually happened around the end of June. The problem with that, he pointed out, was that he needed to have his primary building material—adobes—dried and ready to go before the rains came, usually in the months of June and July. [66] Shoemaker repeated his request in May, 1870, and stated that the adobes were progressing rapidly. He said at that time that he did not want to anticipate or ask for anything irregular, but that if he were allowed to undertake the construction work on the adobe wall at that time he could save the Army money. [67]

He did receive approval to proceed with the work. By June, 1870, the officer's quarters that he had started in April and the adobe wall around the arsenal that was started in June were coming along fast. At that time all of the adobe walls and the roof were finished on the quarters, and half of the foundation was laid for the adobe wall around the arsenal compound. [68]

In September, 1870, a circular was issued that forced Shoemaker to discharge all of his hired force with only a few exceptions. Because of that order, the officers quarters that were under construction at the time were left unfinished despite their advanced state. Also, his ordnance workshops were closed. [69] Shoemaker followed up with a letter to General Alexander B. Dyer stating that in order to construct the new officers quarters at the arsenal, it was necessary for him to take down two of the chimneys and close all of the windows on one side of the old quarters he occupied. Shoemaker again begged to complete his new quarters through the employment of carpenters, a mason, and a painter for three months so that they could finish his quarters. Otherwise, he and his family literally would be out in the cold for the winter. [70]

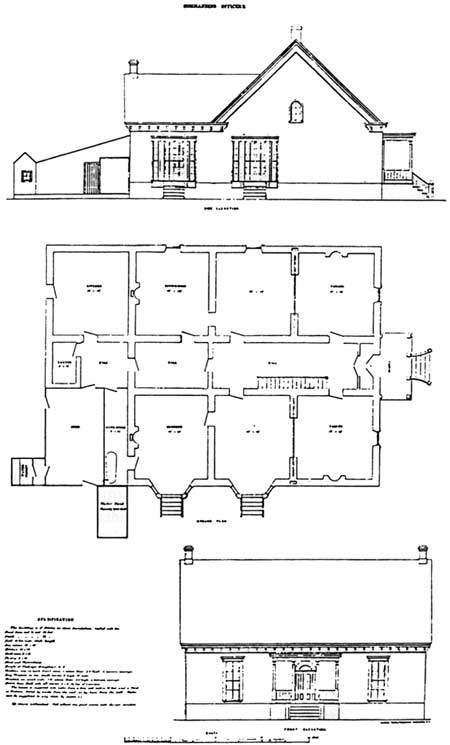

The following spring (1871), work had not yet been completed on the commanding officers quarters (figure 12, HS-114), but from the tone of the correspondence, the work was nearly done. In his estimate to complete the arsenal plans, Shoemaker suggested replacing the office building and the adjoining clerk's quarters. Both were constructed partly of adobes and partly of logs. He recommended that both of those buildings be constructed first, followed by the permanent walls and outhouses, and a small cistern connected with the commanding officers quarters. [71]

By June, 1872, the construction was nearing completion for the arsenal. The appropriation for Fort Union Arsenal for fiscal year 1873 (starting July 1) included $3,500 for "repairing storehouses, magazine, barracks, workshops, office, quarters, enclosing wall, and fences." [72] No monies were included for outright construction.

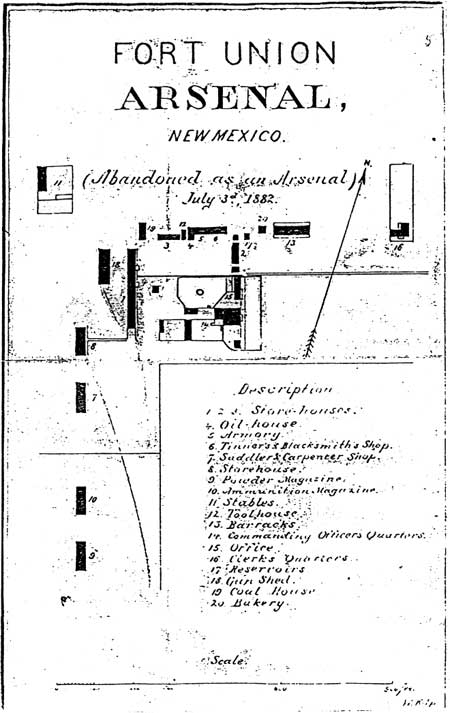

By 1873, the arsenal was virtually complete. In a report for surgeon general, Captain Shoemaker described his feifdom as follows:

Fort Union Arsenal New Mexico is situated one mile due west of Fort Union on a reservation belonging to the ordnance department, one half mile in extent. The arsenal is enclosed by a wall [HS-100] on four sides of one thousand (1,000) feet each. The buildings consists of one set of officers quarters [HS-114], 54 feet front by 75 feet deep, an office [HS-115] 45 feet front by 18 feet deep, one set of barracks [HS-113], 100 feet front by 26 feet deep, with porches front and rear, one set of clerks quarters [HS-116], one armorer [HS-105] and one smith shop [HS-106], one carpenter [HS-108] and one saddlers shop [HS-107], one main storehouse 216 feet long with basement story [HS-101], three smaller storehouses [HS-102, HS-103, HS-118], two magazines for ammunition [HS-109 and HS-110], one stable for public animals with corral [HS-111], small temporary outbuildings to each set of quarters, barracks, shops and storehouses also enclosures.

There is a fine well conveniently situated to supply the Post with an abundance of pure good water, also two cisterns of eighteen thousand gallons each always full in case of fire, with pumps operated by machinery. The buildings, walls and outworks are of adobe, set on permanent stone foundations. The walls of all are heavy and well constructed.

This arsenal is the Depot for supplying the Territory of New Mexico and parts of Texas, Arizona, Colorado and the Indian Territory adjacent thereto. There is a detachment of U.S. Ordnance stationed here, consisting of a commanding officer and 14 men, whose dependence for supplies of Quartermaster Commissary and Medical attendance is on the Depot and Hospital at Fort Union. [73]

Besides overseeing construction of all of the arsenal buildings, Captain Shoemaker took pride in the landscape of his immediate territory. One youthful visitor to the arsenal in 1877 remembered the arsenal as his favorite place. He described the area as having lots of water, fountains with ducks, and flowers. [74] Other documentation included mention of a cut stone sun dial in the "yard" of the arsenal. Shoemaker's men presented him with it. The sundial was removed from the arsenal in 1882. [75]

At about the same time, another observer noticed a few other aspects about Shoemaker the man which she noted in her reminiscences years later. Genevieve LaTourette, daughter of the post chaplain wrote the following:

The Arsenal, which was about a mile from the post, was commanded by Capt. W.R. Shoemaker, who had held that position during 35 or 40 years, and was very highly respected in the surrounding country. That very courtly old gentleman, who evidently did not believe in the progressiveness of that part of the frontier—could not be persuaded to ride on the Santa Fe R.R. when it made its appearance in 1879, and had not been to Las Vegas for many years. He preferred his seclusive life within a certain radius of the arsenal and the garrison, and was constantly in the saddle, a wonderful horseman, even though in his eighties. His eccentricity, perhaps, was due to his extreme deafness, which was a great detriment, yet he could not be persuaded to use remedies—rather (they used to say) preferred to have the ladies put their arms around his neck in order to make him hear—and very loud they had to speak too! [76]

|

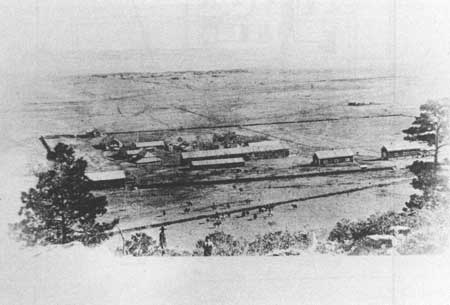

| Figure 14. This photograph (ca. 1882) shows the arsenal installation at about the time of Shoemaker's retirement. He had completed all construction by this stage. Arizona Historical Society. |

Another of his acquaintances remembered him fondly as a deaf widower who had the finest quarters at the Fort and gave superb dinner parties. Because of a spring on his grounds, she recalled, he irrigated his land and had a superb garden. He rode a beautiful Arab horse—unusual for the time period and that part of the country—and allowed special visitors to ride another horse that he kept called "Julieka" after his late wife, Julia. His acquaintance recalled: "I suppose we rode with him nearly every day, the Colonel and I. He had been terribly in love with his wife and yet he never spoke of her, though the garden indeed all that he did, was more or less a kind of going over the things she loved. He showed me her miniature once, a thing he had never done to anybody else out there, then." [77]

By 1882, the railroad had reached that area of New Mexico and the need for a standing army in the west was diminishing. Despite the social changes in the west and his advancing age, Captain Shoemaker continued to oversee his arsenal with the care and control he had always exercised. In the spring of 1882, he wrote to the chief of ordnance in Washington complaining that it was impossible to hire good workers for the arsenal because the mines and the railroads paid higher wages. Those same high wages in the private sector also discouraged men from enlisting in the army. Shoemaker requested some tried and true old soldiers from other arsenals to come to Fort Union Arsenal. He entreated: "It is absolutely necessary to keep the detachment at this Arsenal at its full strength. . . the safety of the public property requires this." [78]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

foun/hsr/hsr5a.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006