|

FORT UNION

Fort Union Memories |

|

|

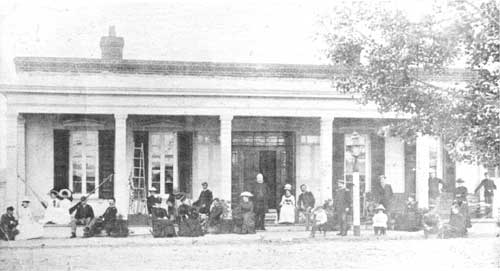

| Fort Union - N. Mex. Post Chaplin's Quarters 1884. Mrs. LaTourrette, Major J. A. M. LaTourrette Post Chaplin, Lt. Col. Henry R. Mixner 10 Inf. Post C. O., Mrs. Gene Lat. Collins |

FORT UNION MEMORIES

By GENEVIEVE LATOURRETTE*

*Daughter of Major James A. M. LaTourrette, Chaplain, Fort Union 1877-1890. Married to Major Joseph H. Collins, Assistant Surgeon, Post Hospital.Submitted for publication by James W. Arrott, Sapello, New Mexico, by courtesy of the late W. J. Lucas, Las Vegas, New Mexico

FORT UNION, N. M., up to the time of its abandonment in 1890, was one of the most important posts on the frontier. It is located on a plateau of many miles of reservation. The quarters are built of adobe—most comfortable both in winter and summer owing to the very thick walls and spacious rooms. The climate is most bracing and healthful, so conducive to health and comfort.

The line of officers' quarters consisted of eight double sets, and facing these across the parade ground were the enlisted men's quarters, mess halls, and the adjutant's office. The line of officers in the quartermaster's depot was separated from the line officers by a road leading to the post traders store and other buildings pertaining thereto. The depot, a continuation of the line officers' quarters, composed of four double sets, followed by quarters of several sets used by the quartermaster sergeants and other employees of the government, and the post quartermaster's office, were separated from the former by a fence which inclosed the q. m. depot on both sides. Opposite the depot officers quarters, across a small parade or square, were the q. m. store houses, and cavalry stables. The hospital was located about four hundred yards outside the post.

Troops stationed at Fort Union during the time my father Chaplain James A. M. LaTourrette was stationed there—September 1877-1890—were the 15th, 9th, 23d and 10th Inf. and the 9th Cav. The Commanding officers of these regiments were—Maj. Edward W. Whittemore, 15th Inf.; Col. G. O. Haller, 23rd Inf., retired for age, and succeeded by Col. Henry M. Black; Col. Henry Douglass, 10th Inf., retired for age, and succeeded by Col. Henry R. Mizner.

The Arsenal, which was about a mile from the post, was commanded by Capt. W. R. Shoemaker, who had held that position during 35 or 40 years, and was very highly respected in the surrounding country. That very courtly old gentleman, who evidently did not believe in the progressiveness of that part of the frontier—could not be persuaded to ride on the Santa Fe R. R. when it made its appearance in 1879, and had not been to Las Vegas for many years. He preferred his seclusive life within a certain radius of the arsenal and the garrison, and was constantly in the saddle, a wonderful horseman, even though in his eighties. His eccentricity, perhaps, was due to his extreme deafness, which was a great detriment, yet he could not be persuaded to use remedies—rather (they used to say) preferred to have the ladies put their arms around his neck in order to make him hear—and very loud they had to speak too!

The arsenal was large and for many years supplied ammunition throughout the territory.

The daily routine of the soldier began with the rising of the sun—firing of the cannon and hoisting of the flag—followed by the bugle sounding call for breakfast—after which there was drilling of various kinds, target practice, etc.; dinner and more drilling, and later in the day recreation—then retreat at sunset—firing of the cannon as the flag was lowered.

I often wonder whether the same flag staff is still standing through all these years since abandonment. I saw the old one fall during a heavy wind storm, several years before we left Fort Union in 1890. It was always the rule of the garrison (and it may be by orders from the War Dept.) to bury beneath the staff various souvenirs or official papers in a box. A box was found when the old staff fell, and I remember witnessing the ceremony with others when the present or last one was put up; however, I doubt whether it is still standing, although one usually lasts many years.

If the flag staff is not there now, the spot where it was could be found directly in front of the commanding officer's quarters which is the center set of the first line of officers quarters, about half way across the parade ground.

The garrison accommodated about twenty-five families—any amount of children—the safest place in the world to bring up children (no automobiles those days). I can remember when a child at Fort Garland the happy days of making mud pies, and riding three at a time on the poor patient burros—the next time I met one of my playmates (the granddaughter of Gen'l. McClellan) was at a reception at the White House in Washington, many years after, where we introduced our children to each other. The social atmosphere in a frontier post, such as Fort Union, in those days, and the happy freedom of all out-of-door life, as well as in, presented an altogether different view with that of the present day. For sports we had horseback riding, tennis, etc.

The remote situation of those garrisons and consequent isolation created an interdependence not found in these days of adjoining large cities and easy formation of friendship in civil life. When so infrequently near cities or small towns where we were able to exchange social courtesies with our civilian acquaintances, it was always a source of regret that Las Vegas was not nearer so that we might see more of our friends who came occasionally, but as a rule only to the larger functions, dinners, dances, and weddings. During the thirteen years of my father's station at Fort Union, there were only five weddings among the officer's families—three daughters of colonels, my sister's and my own. The quarters were well adapted for entertaining—with halls extending from the front door to the back, with large rooms on either side.

In 1885, the prospect of a wedding (my sister Mary's) in the garrison was an event looked forward to with great anticipation, almost everyone taking part in the preparation for the event which was to take place on the 5th of February. The bridegroom elect, 1st Lieut. J. M. Stotsenburg, 6th Cav., was expected to arrive about February 1st.

Out of the clear sky, when everybody was happy and planning for the wedding and all that goes with it, the general assembly was sounded by the several buglers—all running in different directions that all might hear, which means fire or hurried orders to the field of action, and all soldiers fall in formation to receive those orders—generally meaning that Indian renegades were at large. But in this instance orders were received from headquarters at Santa Fe for every officer and soldier who could be spared to leave at sunrise for the opening strip in Oklahoma. Men worked all night, leaving but six enlisted men to care for the post, with two surgeons and the chaplain. As the regiment left, the band, following the usual custom, escorted them out of the garrison quite a distance, playing The Girl I Left Behind Me, which started many a tear to flow. However, the only telegraph instrument left in the garrison (outside of the adjutant's office), in the quartermaster's quarters (the regiment having taken the only operator with it), began to tick about 5 o'clock that evening in a most excited manner, and no one to understand what it meant until the wife of the quartermaster ran from house to house hoping to find someone who could understand the receiving of this message; a young nephew who was visiting us was able to make out enough to let us know the regiment had been stopped at Raton by orders to return to station as it would not be needed. It is useless to say there was great joy in the garrison, as it was very indefinite as to the time of return to their families and it now meant the wedding would after all take place as planned. At sundown the band met the regiment outside the post on its return playing Out of the Wilderness.

A military wedding is a brilliant affair now, and was in this garrison on the frontier of those days: the large halls being spacious and well fitted for such occasions, the entire hall attractively draped with flags and festoons of greens, the band playing both wedding marches and gay music as we left. Officers wore their full uniforms, and relatives and friends in the garrison as well as from Las Vegas attended. No doubt many who are now in that city remember being present at our marriages. Bishop Dunlap (then Bishop of N. M., and living with his family in Las Vegas) officiated at both our weddings. My sister and her husband left for the East immediately after their wedding amid the playing of the band, shoes and plenty of rice being thrown after them. Doctor Joseph H. Collins and myself were married about two years before my sister—we spent two happy weeks at the Old Montezuma Hotel, Las Vegas Hot Springs. On our return to the post, the hop room had been beautifully decorated with flags and greens for a reception by the whole garrison—the usual custom on such occasions, as well as other functions in receiving a bride into a garrison. However, mine was only coming home.

Fort Union was also a center for caring for Indian prisoners until their return to their reservations.

It was in the summer of 1881 that the general assembly call was sounded which sent great chills through the hearts of everybody. On this occasion hurried orders were received by the commanding officer to send all available troops to the field without delay. These orders were sent from headquarters at Santa Fe by request of ranchmen who had been menaced by young renegades who were stealing and killing their bucks. These alarms many times proved to be that they were out more or less for a good time, simply frightening the people rather than to do them harm, and I do not believe they were much worse than our young boys in large cities out for a lark. The troops were off in a few hours—next day was very foggy, so much so we could not see across the parade ground, and while two young Indian prisoners were policing the post they took advantage of the fog and that few men were guarding the post, knocked the sentry down and made their escape. It was said they leaped like two deers through the dense fog, and could not be seen when once in it. They simply flew towards Turkey Mountains, about a mile away, where they hid until dark—making their escape back to their reservation (Mescalero Agency) near Fort Stanton by stealing horses by relays—reaching the Agency in a few days. The result of this great excitement they left behind them, when it was found they were gone, in such mysterious manner, gave the greatest alarm and thrills to each of the twenty-five families, who felt sure they might be hiding in one of their houses. It did not take long for the members of these twenty-five families, mothers, children, to sense something wrong, even the dogs—big and little—whose barking did not add to the serenity of the occasion—only made matters worse. We all started to hunt, for it seemed they really must be somewhere in the post. We went around in bunches, each fearing they might come across them in some crack or corner in their houses or barns, which meant to those who were most nervous sure death, though that would have been more from fright rather than anything else. I know it was the greatest thrill of my life—we even went to the old earth works back of the post, expecting to come face to face with one of them, around one of those corners, where parts were rather deep—when all of a sudden we heard a pistol shot, which proved to be next door to our house. Of course we thought they had been found, rushed home, holding on to each other—only to find that the post surgeon was trying out his pistol to see if it would work in case it was needed. We all drew a sigh of relief, though I am quite sure some of us were almost disappointed that we were not able to prove ourselves a heroine by finding those two young renegades without the assistance of a man—yet secretly in my heart I was glad they escaped without further trouble. That evening was spent in telling of our experiences in the day's excitement. We were all sitting on the end of the porch near the side gate of our yard, when we heard the shuffling of some kind of noise coming toward the gate. All was silent, when a poor little innocent burro poked his head through the gate and gave one of the loudest and most uncanny brays I ever heard—and I had heard many. It can only be imagined what that meant to a flock of frightened women, at a time when we were waiting for something exciting to turn up—however, we drew a great sigh of relief to find it was our nice little old burro; we ended the evening laughing over the affair, but little sleep was enjoyed that night, because we spent the night listening through for noises of all sorts, when all the time those poor Indians were hurrying down to their reservation.

Many times have my thoughts gone back to those days at Fort Union. The numerous interesting events which took place during the 13 years of my father's station there—up to the time of abandonment. An incident happened one day when the mantlepiece of our next door neighbor, which was becoming very loose from the wall, was taken down and replaced. Between the cracks, which evidently were there for many years, articles were found—among them a small old fashioned photograph which proved to be one of my father's cousin—Doctor Peters and family, who had been stationed there about twenty years before we arrived. I have always had the greatest desire to see behind those mantlepieces in every one of those quarters, for I believe many would bring to light other articles of interest—what a tale they might tell.

Toward the latter years at Fort Union, the quarters needed renovating badly. It seemed impossible for the quartermaster to be able to obtain appropriation for repairs. Inspector after Inspector would be sent there to inspect them and even their requisitions would be denied the money by Congress, until the last Inspector came, and that very day we had one of the worst rain storms we ever experienced at the post. Roofs were leaking in the quarters to the extent that we went around with umbrellas. There seemed just one spot in our quarters which was dry where I took my baby in her cradle to the corner of a room. In a few minutes I heard a lusty cry from that corner and found her drenched with rain coming down on her and had to put the top of the carriage up. We really felt compensated to a certain degree that it so happened when the Inspector was there, because it gave him a better idea as to the condition of the quarters. It was not long before an appropriation was forthcoming and all put in perfect condition.

The servant question was a great problem, as we were obliged to send at our own expense to Kansas City and Denver for them, but they would not last long as they married soldiers as soon as possible—until only a few continued to have women servants—finally all but two families replaced with Chinamen for cooks and general housework. Many married from our home—they called it "the Marriage Agency." It happened so many white servants had left that the soldiers did not have enough to continue their weekly dances—their only pleasure of that kind—so they threatened to get rid of these chinese servants by frightening the poor things almost to death by chasing them at night, making them believe they were going to kill them if once they could get them which, of course, was only a scare, but very effective. They would run through our back yards to the front gates, coming out, panting for breath and a smile of relief on their faces, as they saw us on the porch. It was not long before every one of them was gone, and one by one each family returned to their women servants, and the band played on with their dances.

My father, Chaplain James A. M. LaTourrette, arrived at Fort Union, N. M., in September, 1877, from his former station, Fort Lyon, Colorado. It was before the Santa Fe R. R. was built as far as Fort Union. We traveled overland which took a week enroute, and I well remember it was one long picnic, especially after we reached the mountainous region. We had an escort of about ten enlisted men and an officer, for in those days it was not considered quite safe to travel without protection. Our outfit consisted of two baggage wagons (covered), a daugharty, resembling a stage coach, with four mules—the latter was occupied by the family. A new arrival in a garrison in those days was an eventful occasion, and a hearty welcome awaited us. My brother, my sister Mary and myself accompanied our parents, two elder sisters having married some years before. We were entertained, until we were able to move into our own home, by dividing the family into two parts. Col. [and Mrs. John] Dent (Col. Dent was brother of Gen. Grant's wife) was then and had been post trader at Fort Union for some years. They were packing preparatory to leaving for the East. It was fortunate for us as well as for them that my father bought quite a good deal of their furnitureVamong it a bedroom set, the four poster of which they said Gen. Grant had often slept on.

When my father had become established in his new station he very soon was able (in addition to his military duties in the post) to start with his missionary work outside, and did much to promote the interest of the church in that jurisdiction, working in connection with the different bishops of N. M. His services were immediately in demand, especially for weddings—many coming from the country around in addition to those in the garrison. Many an amusing incident happened in connection with these marriages—sometimes the participants coming to our home for the ceremony. Often some of the family would be called in as witnesses. On one occasion, I remember, the bride walked into the room, dressed in a wedding gown made of a nottingham lace curtain—court train, which was very impressive and most effective—the bride looking supremely happy. After the ceremony, while receiving congratulations, one very timid man (a friend they brought with them) wished "many happy returns." He seemed perfectly unconscious of what he had said, and they all left for their farm home very happy.

Another marriage was to take place as soon as the enlisted man's time had expired. The bride elect told with great glee how she used to trot this future husband on her knee when he was a baby. She had recently received quite a sum of money from the Louisiana Lottery, and with this she said they were going on their wedding trip to Albuquerque, and to the grave of her former husband who, some years before, had been hung for murder—they thought it would be so romantic to go there.

My father led a very lonely life in a garrison—there not being any other clergyman nearer than Las Vegas, and those he did not often see; at any rate it was not as though he were in the town, so he enjoyed anyone he could find to talk to, getting into conversation with Mexicans and Indians who came around selling vegetables, blankets, etc. He often amused them for he could not speak Spanish fluently, but did make them understand by mixing a little French, English and some Spanish. However, they seemed to enjoy him and always made it a point to see him, and he always bought something from them whether he needed it or not.

Having been stationed in New Mexico and Colorado for 25 years, with only an occasional trip East, his health became impaired and he contracted heart trouble from living in that high altitude too long. The War Department granted him a leave of one year to recuperate and regain his health. After his arrival in the East, rest and recreation kept him occupied the greater part of the time. He preached all of that summer at St. John's Church, Washington, just opposite the White House, thereby giving the rector of that church a much needed rest, and he also gave many talks in New York, Baltimore, and Washington on the Indians in whom he always took the greatest interest. At Fort Garland, the Utes used to make their stopping place in our back yard, and smoked their pipes with my father in his sitting room. As a result of these lectures on the Indians he was given a number of scholarships at Hampton Institute, Va., and the Carlisle, Pa., Indian School.

Three young lieutenants of the 10th Infantry, who were at one time stationed at Fort Union, became Major Generals in the World War—Gen. R. E. Bullard, Gen. A. W. Brewster, and Gen. E. H. Plummer. All were retired not long after the war.

It also may be interesting to know that our family is now represented by the fourth generation in the army. My father and mother had one son and four daughters. The son went into civil life and the four daughters married in the army. The granddaughters also married in the army, and there are now fifteen great-grandchildren and one great-great grandchild. In 1904 it was said that our family, with one exception, was the largest in the army. My mother and three daughters were left widows—my sister Mary (Mrs. Stotsenburg) and myself are the only ones left.1

1. Mrs. Collins died in 1930. Col. Harry La Tourrette Cavanaugh to W. J. Arrott, November 12, 1950.

| <<< Previous |

memories/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 16-Feb-2010