|

FORT DAVIS

History of Fort Davis, Texas |

|

CHAPTER FIVE:

THE CIVIL WAR YEARS

From the moment of their incorporation into the Union, Texans had long criticized the federal government's inability to protect citizens of the Lone Star state from Indian attacks. Indeed, members of the state's secession convention listed this failure as one of their justifications for leaving the Union. Thus the Civil War would not only force the soldiers of the regular army to examine their loyalties, it would test the skill of state officials in raising, equipping, training, and leading the volunteers so acclaimed by Texans throughout the 1850s.

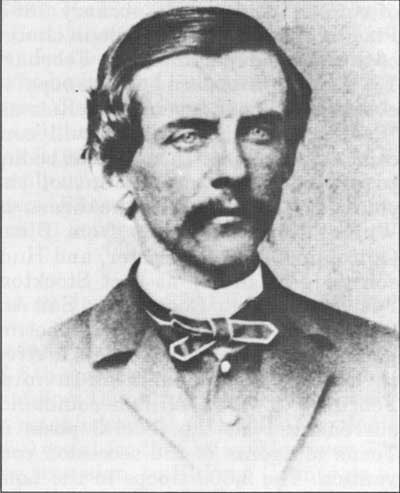

As the dark clouds of secession formed, the immediate question centered upon the fidelities of the frontier regulars. As early as 1856 at least two officers destined to serve at Fort Davis expressed concern over the potential for split allegiances. Both Lt. Edward L. Hartz and Asst. Surgeon DeWitt C. Peters sympathized with former Pres. Millard Fillmore's American Party, but supported the Democratic candidate, James Buchanan, as the man who might heal the nation's sectional wounds. The two officers sternly criticized extremists on both sides. "If he [Buchanan] is elected & our machinery does not work smooth the only thing to be done is to put Massachusetts & South Carolina in ruins," wrote Peters, a native of New York. The Pennsylvania-born Hartz sharply attacked the Republicans and their candidate John C. Fremont. "Men whose only cares are money, money!! money!!! . . . are now striving soul and body to rupture the Union of the states by the accursed fanatical interference in slavery and their support of such an unprincipled scoundrel as John C. Fremont," concluded Hartz, who also lambasted "the fanatic portion" of the South. [1]

Four years later, as rumors of Abraham Lincoln's election and the secession of South Carolina and the lower South swept through Texas, U.S. army officers voiced mixed reactions. Now stationed at Camp Hudson, Hartz blasted both the Republicans and the secessionists. From Fort Mason, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee wrote: "I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union." Yet Lee, a native Virginian who had served his country faithfully for thirty years, decided that "if the Union is dissolved, and the Government disrupted, I shall return to my native State and share the miseries of my people." On the other hand, Rhode Island's Lt. Zenas R. Bliss paid little attention to the recent talk of secession, thinking it was simply more of the same bluster which had characterized national politics for years. Bliss did admit, however, that officers with Southern roots expressed more concern than their Northern brethren. [2]

When a state convention met in Austin on January 28, 1861, to consider relations with the United States government, federal troops in Texas could no longer ignore the issue. Although many Texans, including Gov. Sam Houston, opposed disunion, the convention voted 166-8 to secede on February 1, a decision later ratified by a popular vote. Residents of Fort Davis, heavily dependent on federal protection and the local military establishment, voted 48-0 against secession; likewise, Presidio reported a 316-0 count for the Union. However, El Paso precincts returned some 800 votes for secession, so El Paso County as a whole carried the measure by a healthy majority. The decision led Daniel Murphy, Fort Davis Unionist, to conclude that "there is a poor chance for us for getting any protection in this section of the country." [3]

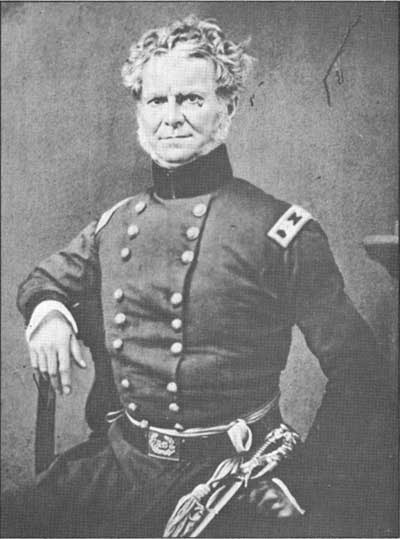

David E. Twiggs, commanding the Department of Texas, acted with dispatch if perhaps not loyalty in response to the situation. Commissioned at age twenty-two during the War of 1812, Twiggs had devoted his life to the service of his country. He had fought in the Seminole Wars, defended Augusta, Georgia, against the South Carolina nullifiers of 1832, and compiled a distinguished record during the Mexican War. Yet the Lincoln election disillusioned the Georgia native, already disgruntled after repeated run-ins with commanding general Winfield Scott. Without informing the War Department, Twiggs initiated correspondence with the governor of Georgia for a position with that state's troops and began negotiations for the army's withdrawal with the secession convention of Texas. [4]

Rightly suspicious of Twiggs's loyalties, the War Department relieved him of command in early February 1861. Placing Col. Carlos A. Waite in charge of the Texas department, on February 15 the army ordered his troops to evacuate to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. "Preliminary thereto, you will concentrate the troops in sufficient bodies to protect their march out of the country," commanded the brass in Washington. Garrisons from Bliss, Quitman, Davis, Lancaster, and Hudson were to gather at Fort Stockton; Fort Clark, Camp Cooper, and San Antonio were other projected meeting points. But the flurry of orders arrived in San Antonio too late. In mid-February, Twiggs, still in command, surrendered all the federal posts in Texas to agents of the secession convention. The 2,600 troops in the Lone Star state, comprising nearly fifteen percent of the United States regular army, were to keep their small arms and to be allowed safe passage to the North. [5]

|

| Fig. 5:12. Gen. David E. Twiggs, commander of the Department of Texas, 1857-61. Photograph 111-B-4024 courtesy of National Archives. |

In conjunction with the surrender, Twiggs ordered post commanders to turn federal property over to state commissioners and to concentrate their forces for a march to the coast. Confused by the abrupt capitulation, officers and men contemplated their loyalties. Twiggs, for one, returned to a hero's welcome in New Orleans and a major general's commission in the Confederate army. Lee, promoted to colonel in mid-March, placed his fate with that of his beloved Virginia; upon the Dominion's withdrawal from the Union in the spring, Lee resigned his federal commission. Farther west, Edward Hartz condemned Twiggs, the Republican Party, and the state of Texas. Although he cast his lot with the Union, Hartz blasted the "Black Republicans" as "fanatics who regard the principles of a political party as paramount to the interests of their country and the welfare of a few miserable negroes of more importance than the perpetuity of the American Union." He also saved a few parting shots for the Lone Star state: "Texas has already cost the U.S. Government millions upon millions and has never brought anything into the Union but her worthless self, her quarrels and her debts." [6]

From Fort Davis, Assistant Surgeon Peters joined a chorus of officers criticizing Twiggs's surrender as "humiliating." "I am one of those . . . who cannot longer regard Genl Twiggs as a veteran, or a Hero," wrote Peters. In contrast to Hartz, however, Peters wished no ill will upon the Lone Star state. "Many of the people in the State are poor beyond means," he noted, and feared that the federal withdrawal would open up the western frontiers to a series of devastating Indian raids, a feeling heartily echoed by local citizens. As for the troops, Peters reported that "every officer & soldier is cheerful & if anything, more loyal than usual." [7]

|

| Fig. 5:13. Asst. Surgeon DeWitt C. Peters. Photograph AA-63, Fort Davis Archives. |

Peters went on to admit that "a few officers have resigned but that is to be expected." Indeed, secession sharply divided army officers in Texas. Of the thirty-one stationed at Fort Davis before the Civil War, ten ultimately joined the Confederate army. Six of the ten were born in states that seceded; John G. Taylor and Edmunds B. Holloway hailed from Kentucky, a slave state that tried to remain neutral. Robert P. Maclay (Pennsylvania) and Philip Stockton (New Jersey) completed the list of those who joined the gray. Of the former Davis officers in the Confederate army, three—Maclay, Thomas M. Jones (Virginia), and Horace Randal (Tennessee)—became brigadier generals. [8]

But twenty-one officers who had served at Fort Davis remained with the Union. Eighteen had been born in Northern states; another, Theodore Fink, was from Germany. Washington Seawell and Richard I. Dodge hailed from slave states but continued their federal service. Of those remaining in the U.S. army, ten won general's stars; two, William Hazen and Zenas R. Bliss, became brevet major generals. The enlisted personnel stationed at Fort Davis at the time of the crisis, belonging to H Company, Eighth Infantry, and the recently disbanded G Company, remained overwhelmingly loyal to the Union. [9]

While considering their options, the troops in West Texas readied for the upcoming move. Insufficient numbers of wagons and draft animals meant that much property would be left behind. Sutler Alexander Young undoubtedly suffered the greatest tangible loss. He loaded as much of his merchandise as he could on available transportation, but sold the rest at absurdly low prices. The small civilian population could not possibly afford to buy all the possessions left behind by the departing military personnel. Surgeon Peters took his own losses philosophically. "Poor people can afford to be charitable," wrote Peters, "& we will give our furniture &c to those who need them & are our friends." [10]

Confusion grew as the isolated Trans-Pecos commands anxiously awaited official news of the national crisis. The lack of specific orders infuriated army personnel. Troops at Fort Quitman received conflicting instructions; their course was finally decided by the arrival of evacuees from Fort Bliss in early April. The two groups united and headed for San Antonio via Fort Davis. Under the leadership of Capt. Edward D. Blake, the Davis garrison seemed more certain of its orders. In April, as advance elements of secessionist troops approached the post, the federal soldiers began their march toward San Antonio. Although he was a native South Carolinian who subsequently joined the Confederate service, Blake cut down the Davis flagstaff in a final act of defiance to the opposing Rebels. The Federals left little behind—"flour about one months rations for a company, no meat, a few 25 lb cans of desicated vegetables, some salt, one bbl vinigar, [and] some wagon sheets." [11]

As the Texas state troops arrived, they found that E. P. Webster and Dietrick Dutchover had been left in charge of protecting the post against vandalism. A Mr. McGee, the sutler's clerk, and Jack Woodland, civilian guide, also stayed at Fort Davis. Two stagekeepers and a handful of Mexican families remained just outside the fort. Otherwise, "our neighbors at the post are few," reported one Confederate. The postmaster had resigned, leaving Daniel Murphy in charge of the mail. The confused new mailman found that his predecessor had taken the mailbox key. "I do not know what to do," Murphy confessed. Meanwhile, the federal troops pressed on toward San Antonio. Led by Bvt. Lt. Col. Isaac V. D. Reeve, the six companies included officers and 366 rank and file. More than 1,300 regulars had already evacuated Texas, with another 800 well on their way to the port of Indianola. [12]

News of the firing on Fort Sumter in mid-April ended the uneasy truce in Texas. About twenty-two miles west of San Antonio near San Lucas Springs, the Union force encountered fifteen hundred Texas troops led by Col. Earl Van Dorn, himself recently resigned from the U.S. Second Cavalry Regiment. Reeve took possession of a large stone house owned by one "Mr. Adams" and barricaded the road to Castroville with his wagons. Van Dorn deployed his troops and a battery of six cannon across Reeve's front and demanded that his foes surrender. Reeve refused to give up until satisfied that the Southerners enjoyed overwhelming strength. Van Dorn met the demand by allowing Lt. Zenas R. Bliss to inspect the Rebel forces. Upon receiving Bliss's report confirming Van Dorn's superiority, Reeve ordered his men to stack their arms. [13]

On May 9, 1861, Reeve officially surrendered his command. The prisoners were distributed at several locations in Texas. Many officers, for example, found themselves sent to San Antonio. Confederate recruiters offered inducements to the captured troops. A few bluecoats joined the Rebel armies; Assistant Surgeon Peters reported that he and two other lieutenants accepted the parole offered by Confederate authorities. Claiming poor health and accompanied by his long-suffering wife, Peters explained that "I understand they [U.S. authorities] do not approve of the course taken . . . but we were tired of having a halter in perspective & so came away on any terms for there was no chance of a fight for us." [14]

Peters also assailed his former captors. They "need a good thrashing. I can never forgive them of their rascally treatment of us. . . . Liberty of speech is gone in the South & they are all crazy as loonies," he asserted. Those who remained in confinement later complained of inhumane treatment. "They were subjected to degrading labors, supplied with scanty food and clothing, and sometimes chained to the ground, or made to suffer other severe military punishments," according to one Eighth Infantry historian. [15]

One of the Confederate guards remembered a far different story. Assigned to oversee prisoners at Camp Verde, he recalled that his charges occupied "comfortable huts" and were "allowed their liberty within a quarter of a mile from the flagstaff." "I had a friendly feeling for the poor old soldiers and did what I could to make their confinement as light and pleasant as possible," he wrote after the war. He claimed that the prisoners attended roll call twice daily and received the same rations as did the Confederates. According to the guard, the Yankees could borrow guns for hunting and leave the camp to attend miscellaneous needs. [16]

Several Union officers initially rejected any favors offered by their Confederate captors. Bomford, Bliss, and several others refused commutation of living allowances offered by the Confederacy. But they gradually accepted parole—Bliss and Bomford were released in April 1862, as was James J. Van Horn, another Fort Davis resident. Colonel Reeve took parole in August. [17]

The enlisted men waited longer for their freedom. At least two soldiers, Stephen O'Connor and a fellow prisoner named Wilson, escaped from near San Antonio in December 1862. They made their way some eight hundred miles to Matamoros, Mexico; there, O'Connor found a U.S. naval vessel which took him to New Orleans, where he promptly reported for duty. Those who accepted a more orthodox release were rewarded in February 1863. On the twenty-fifth of that month, nine noncommissioned officers and 269 men, including many Fort Davis veterans, were exchanged in Louisiana for Confederate prisoners. The soldiers then returned to active service with the Eighth Infantry, their extended stay in Texas finally over. [18]

Having long complained about the federal government's inability to defeat the Indians, Texans now found themselves responsible for their own protection and free to act according to their own policies. In accord with the instructions of the secession convention, military authorities ordered Capt. Trevanion T. Teel's company to occupy forts Clark, Duncan, Lancaster, Stockton, and Camp Hudson. In addition, twenty men of Capt. Powhatan Jordan's troop, led by Lt. Samuel Williams McAllister, were mustered into Confederate service on February 27 at San Antonio and were on their way to Fort Davis within the week. Shortly thereafter, McAllister received a promotion and began raising troops for his own command, enlisting three men at Fort Clark and thirty-two at Fort Davis beginning on April 1. McAllister and several others returned to San Antonio in late August, their six months' obligation at an end. At least fourteen of the men who assembled at Davis remained in the Confederate service, including newly elected Capt. James Davis, 1st Lt. John Kinszley, 1st Sgt. John B. Denton, and Cpl. John Wade. [19]

Supply deficiencies troubled the first Confederate garrison at Fort Davis. Although Daniel Murphy provided a few rangy cattle, the men of McAllister's company nearly mutinied over the lack of proper rations. "It is said there is seven great wonders in the world," wrote D. W. Merrick facetiously. "And our receiving some rations of flour & beans . . . from Ft. Stockton is the 8th wonder." Clothing also ran short, with trousers a particularly scarce commodity. "We are now begining to cast about to remedy the situation," noted a Confederate diarist in late May, although "by keeping out of sight of the Murphy residence we could get along fairly with our shirts." [Mrs. Murphy was at the time the lone woman on the post itself.] Fortunately a former sailor teamed with a tailor in the garrison to fashion some wagon sheets left behind by the departing Federals into rudimentary trousers, thus resolving the immediate crisis. [20]

Several Indians came in to investigate the new occupants of the Trans-Pecos. On May 31 H. W. Merrick reported that the venerable old Apache chief Espejo came in for a "confab" with Captain McAllister. Supposedly 106 years old, Espejo was accompanied by two elderly Indian women. Espejo spoke excellent Spanish, and recounted not only the old days during Mexican rule but also his tribe's warfare with the Comanches. "The Comanches claimed all the country on the east [of the Pecos River]," wrote Merrick, "and his people were not strong no more." [21]

Other Apaches followed the venerable Espejo. Nicholas, a notable Mescalero chief, offered at least one Confederate the opportunity to join his tribe by marrying one of his daughters. The Indians traded mescal cakes, bows, shields, arrows, lances, and clothing in return for scrap iron, ore, and liquor. According to Merrick, Espejo "loves" whiskey, but admitted that it rendered younger warriors "fools." [22]

The Confederates quickly became bored with life along the Limpia. Occasionally rumors of fighting back east or moves to the west excited the recruits. Four soldiers wasted a day hunting for copper, silver, and big horned sheep. Several troopers idled away July 4 by firing off a few shots with the unit's howitzer. One of the boys "did not elevate the piece quite enough. The shell struck the edge of the bluff and came ricocheting down the mountain in a direct line with the gun. And the boys in a direct line away from it." "Exploded at the foot of the mountain," wrote one diarist nonchalantly. "He had cut his fuse too long." [23]

Meanwhile, department commander Van Dorn set out to clear up the confusion resulting from secession. On May 24 Van Dorn formally ordered the reoccupation of the Federal forts in West Texas. Lt. Col. John R. Baylor, a noted frontiersman and second in command of the Second Texas Mounted Rifles, headed the first occupation forces. If possible, Baylor was also to seize Fort Fillmore, forty miles north of El Paso. [24]

Company D of Baylor's regiment had helped capture Colonel Reeve's column west of San Antonio in May. As part of Baylor's drive into New Mexico, D Company reached Fort Davis on July 7, 1861, thereby reinforcing McAllister's forlorn garrison. Capt. James C. Walker commanded the outfit. Born in London in 1812, Walker emigrated to the United States while still a child. He attended West Point from 1828 to 1831, but "a deficiency in mathematics" led him to quit the Academy to study medicine. He served in the war with Mexico, and moved to Lavaca County, Texas, in 1854. There Walker helped recruit his company, which was mustered into Confederate service on May 23, 1861. [25]

After briefly occupying Fort Davis, Walker and most of D Company continued west with Baylor to El Paso and New Mexico. Baylor occupied Mesilla, New Mexico, captured the Union forces which had concentrated at Fort Fillmore, and organized the Confederate Territory of Arizona. Meanwhile, Lt. William E. White and Lt. Reuben R. Mays took charge of Fort Davis until the arrival of Capt. William C. Adams, commander of C Company, Second Regiment of Mounted Rifles. Hoping to protect the western frontiers, Adams had raised his command in February 1861, upon the authority of Ben McCulloch. "You had better get such men as wish to join the service for twelve months," McCulloch had advised. "Get the best horses you can & get them in good order." [26]

State and Confederate authorities sought to establish order amidst the excitement and confusion following the onset of the Civil War. Baylor already held parts of southern New Mexico and Arizona but needed more men to consolidate his gains. Back in Texas, John S. "Rip" Ford, former Ranger and pioneer, commanded the Rio Grande line from Brownsville to El Paso. Van Dorn warned Baylor and Ford of the presence of several hundred U.S. soldiers within range of El Paso. With the aid of the five or six cannon seized at Davis, Quitman, and Bliss, Van Dorn believed prompt action might bag the entire enemy force. [27]

Although Baylor defeated the Federals above El Paso, delays in organizing, equipping, and training recruits prevented the Confederates from exploiting the early advantage. Col. Paul O. Hebert, who replaced Van Dorn as commander of the Department of Texas, noted that "although volunteers are anxious to serve, the people are poor and the state without money or apparent credit. . . . [A]rms, ammunition, provisions and equipments are wanting." Disciplining the independent-minded Rebels seemed a dubious but necessary proposition. Gambling, horseracing, and stealing from civilians must immediately end; "if any gamblers come to the posts or about them to filch the troops of their earnings [you] will order them to stop their gambling or require them to leave at once," wrote one frontier adjutant. Though retaining their individual approach to warfare, Adams's men were decently armed, their commander having drawn sixty-five cavalry musketoons and a similar number of Colt revolvers from Confederate stocks in San Antonio. [28]

Baylor impatiently pressed ahead. On July 12, 1861, he ordered Captain Adams to move most of his command to Fort Bliss, leaving only twenty men and a second lieutenant at Davis. As one delightfully semiliterate Confederate remaining at Davis remarked, "ther are only 20 men at the post now the others are gone with the Captin to Fort Filmore to Col Baylor in persait of them northern troops." Realizing that this might leave the Trans-Pecos open to Indian attack, Baylor sought a truce with Chief Nicholas, a local Apache leader. After briefly meeting an Indian delegation at Fort Davis, Baylor wined and dined the chief at El Paso. The colonel also issued food supplies from Fort Davis to Nicholas's people. In return the Apache chief agreed to make peace. But as his stagecoach approached Davis, Nicholas stole two pistols and made a daring escape. [29]

The shaky truce was shattered by early August. "We have just com from a five days scout yesterday we kild two Indians and tuck one with us a Life he is hear with us now," scribbled a Fort Davis trooper, who believed two hundred Indians roamed the area. On the night of August 4 the Apaches killed or captured fifty animals belonging to sutler Patrick Murphy. Lt. Reuben E. Mays set out in pursuit the following day with six men of D Company, Second Texas Mounted Rifles—Thomas Carroll, John H. Brown, Samuel R. Desper, Frederick Perkins, Samuel Shelby, and John S. Walker. Juan Fernandez, another unnamed Mexican, and five Anglo civilians—John Turner, post guide; P. H. Spence, stage keeper; John Woodland, a former Ranger; Joseph Lambert; and John Deprose, clerk to Patrick Murphy—joined the soldiers. [30]

Lieutenant Mays followed the Indian trail for more than one hundred miles to the southeast. On August 10 Mays captured a hundred Apache horses, but blundered into a neatly laid ambush the following day. Only one of the party, a Mexican guide named Juan Fernandez, escaped the Indian trap. Fernandez stumbled back to Fort Davis, where Lt. William P. White sent out nineteen men, including nine members of the garrison, as a relief party. From Fort Stockton, Captain Adams also took up the pursuit, with Fernandez as guide. Adams and his men nearly ran out of water in the desolate region south of present-day Alpine as they vainly searched for the Indian raiders. The Fort Davis team located the site of the disaster, but found only the body of John Deprose, scraps of tattered clothing, and a few miscellaneous personal items. [31]

Baylor learned of the disaster by August 25. Formerly the colonel had been satisfied with stationing small detachments of twenty to thirty men at each of the Trans-Pecos forts. But in light of the recent defeat, Baylor ordered Captain Adams to concentrate his entire company at Fort Davis. Such a move, he hoped, might better protect the road to El Paso. Baylor also demanded reinforcements for his operations in New Mexico and western Texas. In accord with Baylor's instructions, Adams returned to Davis on September 7, finding Lieutenant White, Sgt. J. B. Hawkins, and fourteen privates at the post. By the end of the month, the beefed-up garrison included officers Adams, White, and Lt. Emory Gibbons, five privates left behind as sick by other companies, fifteen men from D Company, and forty-eight men from C Company, Second Texas Mounted Rifles. [32]

In early October, Captain Adams rode back to Fort Lancaster to guide additional recruits to Fort Davis. In the meantime Colonel Baylor ordered the capture of one A. F. Wulff, a contractor to Fort Davis who also operated a store in Presidio del Norte, Mexico. According to Baylor, Wulff was "a spy." "I want him enticed over on this side of the river and taken prisoner and sent to these headquarters [Dona Ana, New Mexico] in irons," wrote Baylor. The order reached Fort Davis on the eleventh; in Captain Adams' absence, Lieutenant Gibbons assumed responsibility for carrying out these instructions. Oddly, Gibbons requested that Richard C. Daly, a former soldier now serving as clerk at Pat Murphy's trading house, read the message aloud. Daly did as he was told, with several bystanders at the store overhearing the contents of the letter. [33]

Taking nine men, Lieutenant Gibbons left Davis the following day. On the fourteenth, four of his party, traveling incognito, appeared at Wulff's store in Presidio del Norte. They returned again that afternoon, further quizzing Wulff. The storekeeper later claimed that he believed the men to be Confederate deserters and was as such suspicious of their motives. Captain Adams, however, pointed out that since Wulff and Pat Murphy were business partners, the latter had undoubtedly passed a warning on to his associate ahead of the Gibbons scout. [34]

Several Confederates remained on the Mexican side of the border that evening, attending a dance with Joseph Leaton, son of the deceased land baron Ben Leaton. Six men—five soldiers from Fort Davis and Joe Leaton—banged on Wulff's door about three o'clock the next morning. Gibbons claimed that they had been invited to spend the night there. Cautiously, Wulff opened the door. Two Confederates grabbed Wulff and threatened to shoot him if he did not come quietly. Fearful for his wife and family, the accused spy promised to cooperate. [35]

As the Confederates dragged Wulff through the streets, his wife screamed for help. On the alert after hearing about the open reading of the Baylor letter at Fort Davis, Wulff's brother-in-law formed a posse which chased down the Americans. Shots rang out in the early morning streets of Presidio; when the smoke finally cleared, two of the soldiers (Thomas B. Wren from Uvalde and John B. Boles from San Antonio) and an unidentified Mexican were killed. Wulff broke free and escaped unharmed. As he later informed his friend and partner Murphy, "Providence seems to protect me—this time I did not expect to see my family again. . . . Joe Leaton was the one that laid the plot no doubt." [36]

Adams had returned to Fort Davis on the fourteenth, the day before the incident at Presidio del Norte. He dispatched Sgt. T. L. Wilson and five men to recall Gibbons, "but too late to remedy the evil the lieutenant has caused." Adams blamed the fiasco squarely on Lieutenant Gibbons, whose decision to have Daly read the letter accusing Wulff of espionage "entirely ruined the success of the undertaking." Upon Gibbons's return to Fort Davis on October 18, Adams placed the lieutenant under arrest. [37]

Available evidence can prove neither Baylor's allegations that Wulff was a spy nor the latter's claim that Joe Leaton had instigated the attempted abduction. The incident did, however, lead Wulff to abandon his contracts with the Confederates at Fort Davis. He and Murphy had been supplying the post with hay, were just beginning to fulfill a contract for one thousand bushels of corn (at three dollars per bushel), and had also agreed to furnish small quantities of wood to the Confederates. But in the wake of his near escape, Wulff concluded that "we might just as well give up furnishing Fort Davis." From New Mexico, Colonel Baylor agreed. On November 15 he ordered Captain Adams to make no more contracts with Murphy and Wulff. [38]

The misadventure also helped to oust Patrick Murphy from the Davis sutlership. In accord with the original surrender by General Twiggs of federal posts in Texas, Rebel officials tried to locate the proper landowners. Although Patrick Murphy initially claimed the sutler's post at Davis, John James was renting the store at Davis for twenty dollars a month to the firm of Moke and Brother by September 17. Despite the James lease, Murphy apparently contested the case until early December, when authorities ordered Captain Adams to give "Moke and Brother" the sutlership. As late as March 1862 Adams was still defending himself against charges that he had delayed recognizing the Moke and Brother claim. [39]

By the end of October the Confederate garrison at Fort Davis had settled into more routine duties. Acting Asst. Surgeon C. E. R. King had relieved W. J. McClain as post doctor. Captain Adams claimed the commanding officer's quarters formerly occupied by Captain Walker, who later notified his successor that he had left the house "in disorder & everything strewn around expecting to be back in a few days." Walker continued, "I hope you [Adams] have my goods & things stored away, & [have] taken care of as many of them as are of value to us." Another Texan, John Draper, had already grown tired of military life. "I think when ever I git home," he speculated, "I will be able to bye me a farm and settle myself for life for I think the war will be all over by that time and if it is not I know not what I shel do." Corn and hay were plentiful, but the paymaster was long overdue. Draper hoped he would be paid "sum day." [40]

The garrison was still woefully small. Of C Company's officers, only Adams was present and ready for duty at Fort Davis. Gibbons remained under arrest; Lt. John C. Ellis was at Fort Lancaster; Lt. John M. Ingram had accompanied Baylor as far as Fort Bliss. Fifty-one of the company's enlisted men lived at Davis, with thirty-one others at Fort Stockton. Although eleven troopers on detached service from D Company lent added strength, the sixty-two men stationed there scarcely inspired confidence in the young nation's ability to defend West Texas. For one, Captain Walker feared that an impending Union offensive would force Baylor to fall back to Fort Davis and gather reinforcements. [41]

Indeed, the combination of losses to Indian attack and the threatened Federal invasion worried many Confederates. Like Walker, John Draper predicted major changes in the near future. The Fort Davis garrison had only twenty-five rounds per man. He calculated that even after Baylor's projected retreat, a mere eight hundred Rebels would be up against twenty-five hundred Yankees. "But I think we can whipe them two to one," Draper exclaimed, "for they ar all Greasers or one half of them." Already bloodied by the loss of several acquaintances in the fighting, Draper urged friends back home to "do soum thing for [their] country." [42]

More troops were indeed on their way. Henry H. Sibley, inventor of the famous Sibley tent and veteran of more than twenty years' distinguished service in the United States Army, had resigned his commission to join the Confederay in May 1861. Formerly stationed at Taos, New Mexico, Sibley rushed to Richmond, Virginia, where he met with Pres. Jefferson Davis. Something of a romantic, Sibley believed that a Rebel invasion of New Mexico could be self-supporting. Furthermore, it might precipitate a Confederate push to California. Impressed by the presumed ease of such a move, Confederate officials authorized him to raise two regiments (Sibley later increased that number to three) and one battery of howitzers and to seize New Mexico. [43]

Overly optimistic planning and inadequate supplies plagued the Sibley expedition from the outset. Marching in small groups to best exploit the area's limited water, elements of the Fourth Regiment Texas Mounted Volunteers reached Fort Davis in late November and early December. One enlisted man noted that two officers "stayed behind and tanked up considerably." Ignorant of the terrain, the company passed Barrel Springs and made a dry camp on the open prairie. Further misfortune awaited the unfortunate Texans at Van Horn's Wells—an earlier wagon train had taken all the water! Troops with the Fifth and Seventh Regiments entered Limpia Canyon in mid-December. Disheartened by the poorly conducted, treeless march so far, the local terrain proved a welcome change for many of the exhausted soldiers. "Some pretty tall mountains for Texas," jotted W. R. Howell. "Mountain scenery very fine—so likewise the water—trees all round." [44]

A mutiny, apparently stemming from the lack of bread, shook Howell's camp on December 14. In an effort to mollify the restless troops, officers issued passes to Fort Davis the following day. Many of the poorly clad soldiers purchased all available clothing from the post sutler; others seized the chance to "get tight." A few, including the more cerebral Howell, mailed letters via the increasingly irregular but still operable postal system in West Texas. The brief interlude provided a welcome respite for these members of the Sibley Brigade, who resumed the march west on the sixteenth. [45]

Normalcy returned as the main columns departed. Sporting an exotic array of uniforms, personal clothing, materials purchased from the sutler, and garments supplied by friends, relatives, and citizens' groups back home, the Confederate garrisons of West Texas were too small to undertake much formal military training. The variety of their arms paralleled the wide assortment of clothing; musketoons, Springfield rifle-muskets, Sharps carbines, and Colt pistols were the most prevalant weapons used by the Confederates. At sister post Lancaster, Texas, soldiers played an early version of baseball called town ball. [46]

Food became more plentiful, with rations resembling those of the U.S. troops who had preceded the Texans. Lt. J. C. Ellis purchased 36 lbs. of beef, 110 lbs. flour, 10 lbs. coffee, 10 lbs. sugar, 2 quarts salt, 2 lbs. 5 oz. tea, 1 lb. 4 oz. molasses, and 2 lbs. soap from the sutler for the officers' mess during December, his account totaling $13.69. The purchases of Captain Adams between August 1861 and January 1862 suggest that Moke and Brothers maintained a sizeable stock of merchandise. In addition to his normal rations, Adams bought tobacco, a wash bowl and basin, a pitcher, shoes, socks, envelopes, a pocket knife, sugar, tea, a tin pan, and a wool hat. Canned delicacies included pineapples, sardines, preserves, green peas, pickles, oysters, and strawberries. Cognac, two bottles of brandy, and four bottles of champagne rounded out Adams' grocery list, which totaled $72.60. [47]

On December 27 an Indian raid on Patrick Murphy's cattle herd reminded the troops of their exposed position. Lieutenant Ellis's pursuit party left only Captain Adams, Lt. John M. Ingram, Assistant Surgeon King, and twenty-one enlisted men at Davis. The rest of the company were either at Fort Stockton or in the field with Lieutenant Ellis. Another four men from the Sibley columns remained at the Davis hospital; eleven other soldiers were there on assorted escort duties. Smallpox swept the post in early January; from Fort Lancaster, an apprehensive Rebel private noted that "Fort Davis is the next Post above here. The Small Pox is getting rather close to be comfortable." [48]

Next to eluding the mysterious smallpox virus, avoiding boredom remained a chief concern at the Davis garrison during the first months of 1862. Several enlisted men ran up impressive bills with local merchants. By May, Patrick Murphy claimed that Pvt. G. T. Haney owed him $119.67 for clothing and other articles; W. O'Bryan nearly matched the prodigal Haney with a bill of $115.18. Escorts, mail parties, and soldiers in need of medical care arrived periodically as the West Texas garrisons were reshuffled. Captain Adams departed the post for San Antonio on March 13. Lieutenant Ingram led a detachment of C Company to Fort Lancaster two and a half weeks later, leaving Ellis as the only combat officer at Fort Davis. Between March and May an average of only twenty-nine soldiers guarded the post on the Limpia. The small number of troops precluded any significant military activity. [49]

Few records document the activities of the dependents of the Confederate garrison. Captain Adams brought his family out to Fort Davis. A few women and children lived in the outlying settlement, although contemporary writers largely ignored their presence. The ladies of the area did win the gratitude of one private for the friendly reception they gave the Sibley Brigade. [50]

But the destiny of Fort Davis now lay with Sibley's twenty-five-hundred strong Army of New Mexico. Notorious for his heavy use of alcohol, Sibley expected that his men could rely on local sources of supply. But it was now too late in the season. Stuck in New Mexico in mid-winter, his army found obtaining food, ammunition, and clothing increasingly difficult. Too, Federal opposition organized by Col. Edward R. S. Canby proved stronger than anticipated. Although victorious at the Battle of Valverde (February 21, 1862), the loss of the Confederate supply train at Glorieta (March 28, 1862) forced Sibley to abandon his dreams of conquest. Burying most of their cannon and leaving those soldiers most in need of medical attention behind, the Confederates began the long trek back to Texas. [51]

Sibley's once proud Army of New Mexico disintegrated as a fighting force during the retreat. Shortages of food, medicine, clothing, and water ruined morale. In the words of one Rebel, "Be it known that we did not march in line, but every man for himself and the wagons take the hindmost." Another reported bitterly:

We ate for breakfast this morning a rib or two of an old broke-down work ox we had along, without salt. Yesterday two men were left on the road, too sick to be moved. We also left two in the mountains near [Fort] Craig. They were thrown out of the wagons by Major [Richard T.] Brownrigg and one out of [the] end of Sibley's wagon. Sibley is heartily despised by every man in the brigade for his want of feeling, poor generalship, and cowardice. Several Mexican whores can find room to ride in his wagons while the poor private soldier is thrown out to die on the way. The feeling and expression of the whole brigade is never to come up here again unless mounted and under a different general. [52]

Of the twenty-five-hundred-man invasion force, only some eighteen hundred effectives returned from New Mexico. Sibley and his headquarters staff departed El Paso in June. Col. William Steele's rearguard followed shortly thereafter, thanks to the excessive caution of the Union commander Canby, who feared that his spearhead detachments might become overextended. Most of the Rebels gladly left New Mexico. One officer labeled the territory "one of the most miserable God forsaken countries on the face of the earth. . . . The miserable God forsaken race of human beings which now inhabit it . . . ought to have it, and so far as I am concerned they are welcome to my share of it." Indian raiders multiplied the plight of the rabble by filling Trans-Pecos water holes with dirt and sheep caracasses. [53]

State and Confederate officials desperately tried to relieve the starving Sibley Brigade. Department commander Paul O. Hebert ordered Col. X. B. DeBray to march to Sibley's relief in early May. Flour was to be delivered at Fort Davis and beef taken on the hoof between San Antonio and El Paso. Fort Davis was designated a receiving station for the sick and wounded. In conjunction with the proposed move, Capt. Angel Navarro organized a company to take over the garrison there. Navarro instructed prospective recruiters to secure volunteers who "have a horse and if possible good armament." Capt. H. A. Hamner's H Company of the W. P. Lane Rangers also briefly occupied Fort Davis. [54]

In accord with these efforts, Fort Davis became a crucial supply depot for Sibley's haggard command. Moving in small detachments, the ragged groups found ample supplies at the outpost on the Limpia. One soldier, Theo Noel, remembered that his party secured enough wood to bake coarse flour into dough. They also "'gourmandised sumptuously' on fat beef, the first for many a long day." Legend also holds that the exhausted Rebels buried two cannon somewhere near Fort Davis. Although the two fieldpieces have not been located, the confused nature of the retreat makes such action plausible. [55]

As Steele's rearguard abandoned the Trans-Pecos, the Confederate occupation of Fort Davis ended. General Hebert had long ago revoked his previous instructions ordering DeBray to move into West Texas. From Mesilla, Colonel Baylor's last-ditch efforts to end the Indian threat by extermination also failed. In March, Baylor had called upon a subordinate "to use all means to persuade the Apaches or any tribe to come in for the purpose of making peace, and when you get them together kill all the grown Indians and take the children prisoners. . . . Leave nothing undone to insure success, and have a sufficient number of men around to allow no Indian to escape." Upon learning of his extermination policy, Confederate authorities stripped the over-eager Baylor of his command. [56]

Capt. Angel Navarro's detachment probably represented the last permanent Confederate garrison at Fort Davis. As the Rebels abandoned the post, Diedrick Dutchover remained behind along with several civilians, one of whom was quite ill. The Apaches quickly seized the chance to destroy the white man's outpost. For two days and nights, Dutchover and the refugees hid on the roof of a building while the Indians looted the fort. The terrified Dutchover group finally abandoned the sick man and began the ninety-mile trek to Presidio. The escapees arrived safely in the border town; one body, apparently that of the sick man, was found by a subsequent stage party and later by advancing Federals. [57]

Texans braced themselves for the worst in the wake of the Sibley debacle and the growing likelihood of amphibious invasion along the Gulf coast. General Hebert declared martial law. And as Union troops under Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton began moving against Fort Bliss, Hebert ordered that all posts west of Fort Clark be evacuated. "To invade in that direction the enemy have a desert without water to cross," he assured the worried governor of Texas, Francis R. Lubbock. [58]

Carleton began his counterthrust on August 16, when he advanced on Fort Bliss with three companies of cavalry. At the little settlement of Franklin, he found twenty-five sick and disabled Confederates left behind by Steele's rear guard. Carleton's troops also recovered twelve wagonloads of medical and quartermaster's supplies. The Yankees then moved against Fort Quitman; elements of his command hoisted the Stars and Stripes over the old post on August 22. In explaining his move down the Rio Grande, Carleton noted:

The object of my march was to restore confidence to the people. They had been taught by the Texans that we were coming among them as marauders and as robbers. When they found we treated them kindly and paid them a fair price for all the supplies we required they rejoiced to find, as they came under the old flag once more, that they could now have protection and will be treated justly. The abhorrence they expressed for the Confederate troops and of the rebellion convinced me that their loyalty to the United States is now beyond question. [59]

On the twenty-second, Carleton ordered Capt. E. D. Shirland to take his Company C, First California Cavalry, to occupy Fort Davis. The reconnaissance was occasioned by rumors that Steele had left fifty to sixty wounded there under the guard of Captain Navarro's "company of troops of Mexican lineage." Hampered by the fouling of several waterholes by Indians, Shirland nonetheless reached Barrel Springs on the twenty-sixth with twenty men. He dispatched two soldiers and a Mexican guide to reconnoiter Fort Davis the next day. [60]

Upon the scouting party's return, Captain Shirland proceeded to Davis with the balance of his little command. The Federals found one arrow-ridden body at the overland mail station. After burying the corpse, the Union detachment inspected the post. Shirland compiled a detailed report of the remaining buildings, at least three of which he found burned or destroyed. All property save some iron, a wagon full of lumber, a few horseshoes, two wagons, several wagon wheels, empty barrels, some chains, and a number of dilapidated hospital bedsteads had been removed. Finally, the captain informed superiors that he had been told "that the entire fort was sold by the Confederate States officers to some party at Del Norte, Mexico." [61]

Shirland departed Fort Davis on August 30. The next day, six mounted Indians carrying a white flag approached his column ten miles west of Dead Man's Hole. Twenty-five or thirty more mounted men soon appeared, followed by a large party on foot. "Wishing to get rid of the footmen, I made a running fight of it, expecting the mounted men to follow," reported Shirland. "Finding it too hot for them, they returned," he noted, leaving behind four dead. The captain claimed twenty Indians wounded. As he continued his retreat to El Paso, Shirland, for unspecified reasons, also arrested two Mexicans who were en route to the east. [62]

General Carleton praised Shirland's gallantry and execution of orders. Supply shortages and the impending withdrawal of much of his command, however, prevented Carleton from continuing his move into the Trans-Pecos, save the continued occupation of El Paso. He paroled more than one hundred captured Confederates and established his departmental headquarters at Santa Fe. Carleton then focused his attention on Navajos and Mescalero Apaches in New Mexico, whose attacks on non-Indian settlements had increased since the outbreak of the Civil War. [63]

Carleton urged Col. Christopher Carson to "make war upon the Mescaleros and upon all other Indians you may find in the Mescalero country, until further orders. All Indian men of that tribe are to be killed whenever and wherever you can find them." In addition to ruthlessly defeating the Indians, Carson should post small parties to watch approaches to New Mexico via the Pecos River, the Hueco Tanks, and Fort Quitman. Rumors of another Confederate offensive in West Texas were evident by mid-November, when Union agents reported that Baylor was organizing six thousand men at San Antonio to link up with secessionists in El Paso. Though increasingly skeptical of such information, Carleton planned a scorched earth policy in case of a renewed Rebel thrust. By gathering all the grain in the region at Mesilla, the Confederates would be unable to cross West Texas without massive preparation. [64]

Union authorities near El Paso were not so sure. They worried that the Confederates might secure supplies from Chihuahua. Henry Skillman, the former overland mail boss, seemed a particularly dangerous foe—this "noted desperado" "dropped from the clouds" into El Paso in late November 1862, fueling additional rumors about Confederate intentions. Skillman certainly dressed the part. "He carries several revolvers and bowie knives, dresses in buckskin, and has a sandy hair and beard. He loves hard work and adventure, and hates 'Injuns,'" one observer had written in 1858. From Mesilla, Col. J. R. West stepped up his patrols in West Texas by dispatching "Brad. Daily and Captain Parvin" to watch the Horsehead Crossing of the Pecos. Carleton journeyed to the El Paso area to investigate the talk of Confederate aggression; he returned convinced that the Indians remained the greatest threat to Federal control over New Mexico and Arizona. [65]

Despite Carleton's assurances, the possibility of Confederate assault haunted Federal officials in El Paso through the spring of 1863. Maj. David Fergusson rode to Chihuahua to speak with Mexican officials and to establish contacts with local businessmen who maintained connections in San Antonio. He also convinced Union sympathizers in Mexico to scout the Trans-Pecos, including abandoned Fort Davis, for signs of an impending Confederate advance. Also vigilant was J. R. West, now commanding Union troops outside El Paso. In addition to sending a Mexican spy down to Presidio del Norte to watch for the passage of supplies to Texas, West ordered Captain Shirland back to Fort Quitman and maintained a picket at Hueco Tanks. Convinced that his position was in danger, West asserted "that sooner or later this summer a large force from Texas will be moved against this Territory." [66]

Carleton remained calm. "I cannot believe any large force from Texas is en route to invade New Mexico and Arizona at this season of the year," he advised superiors on April 23. Carleton's assessment proved correct. Although a few diehard Confederate sympathizers like Skillman and long-time Presidio resident John D. Burgess assured Southern authorities that such a thrust could be supplied, Texas could scarcely defend herself, much less launch another offensive. Sibley's brigade had returned from New Mexico an unarmed mob. Deeply concerned about the Union occupation of Galveston and the threatened assault on the southern coast of Texas, department commander Hebert pleaded for additional men. A poorly armed, poorly organized Frontier Regiment of Texas State Troops grimly hung on to a line of posts from Fort Clark to Montague County. [67]

Unconcerned about a new Rebel offensive, Carleton was keen on bringing the attempted kidnappers of A. F. Wulff to justice and wholeheartedly supported efforts to clean up the "ruffians" based at Fort Leaton. He authorized the governor of Chihuahua to cross the river and arrest the gang. Among the gang's ringleaders was Edward Hall. Claiming to be an authorized Confederate agent, Hall sold property looted from Fort Davis in Chihuahua. "Justice has a strong claim on this bad rebel," reported Major Fergusson. Carleton proclaimed that Hall "should be dealt summarily with. A stern example should be made of such a ruffian." [68]

In April 1864 Union troops took care of the problem. Under the guidance of Capt. Henry Skillman, a few Confederates had maintained an irregular communication with Southern supporters in Mexico. On the third, Capt. Alfred H. French and twenty-five men of A Company, First California Volunteer Cavalry, marched to Presidio del Norte via Fort Davis. Twelve days later French surprised Skillman's "Texas spy and scouting party" at Spencer's Ranch. The Federals routed the astonished Rebels, who lost three killed (including their commander), two others mortally wounded, and four men and nine animals taken prisoner. French reported no losses. [69]

Both sides launched occasional forays into the Trans-Pecos throughout the Civil War. Texas state militiamen defeated a collection of deserters, adventurers, and California-bound emigrants west of Fort Lancaster in April 1864. W. A. Peril led a cattle drive from Fort McKavett to Mexico past Horsehead Crossing, Fort Stockton, and El Paso. In the absence of permanent military garrisons, however, non-Indian movement across the Trans-Pecos was a risky undertaking. A Mexican salt train, for example, was attacked near Fort Quitman. Apaches killed all thirteen men, burned their wagons, and captured their oxen. [70]

Without the assistance of federal troops and with her own energies largely devoted to events to the east, the Lone Star state had been unable to defend her western frontiers. In January 1865 migrating Kickapoo Indians embarrassed a force of Texas militiamen at the Battle of Dove Creek. Civilians abandoned their frontier settlements or desperately "forted up" in hastily constructed blockhouses against Indian attack. The situation grew worse as it became impossible to devote arms, ammunition, or manpower for western service. Texas's collapse proved complete in early June 1865 when, following the capitulation at Appomattox of Robert E. Lee, Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the Trains-Mississippi Department. [71]

Indians and looters had long since vandalized and burned the military buildings comprising the federal fort on Limpia Creek. The regular army's efforts during the 1850s to protect the overland trail, encourage non-Indian settlement of the Trans-Pecos, and defeat the region's indigenous peoples had come to naught. At the onset of the war, troops stationed at Fort Davis generally cast their lots with the Union, although a significant number of former officers associated with Davis joined the Confederate cause. After the federal evacuation, state and Confederate forces occupied the post, using it as a supply, recruiting, and medical center for the ill-fated Sibley invasion of New Mexico. By mid 1862, however, the Confederacy's western empire had collapsed, and the Rebels left the western Texas frontiers in disarray. As major theaters of the sectional conflict emerged elsewhere, both sides left the Trans-Pecos virtually unoccupied. Only the hardiest residents and overland emigrants braved the new wave of Indian attacks which reigned down upon West and Central Texas. Texas, like the United States government before it, had failed to overcome Indian opposition to outside authority.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

foda/history/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2008