|

FORT DAVIS

Administrative History |

|

Chapter Seven:

Refining the Message, Defending the Resources: The Quest for Institutional Support, 1980-1996 (continued)

Given the ongoing problems of operating an historic site with limited staffing, Doug McChristian decided in December 1981 to speak forthrightly about the "core mission declaration" requested by the Southwest Region. He oversaw a park unit with some 120 buildings and ruins, not to mention "an unknown number of structure sites, especially with regard to the First Fort area, [that] remain to be located precisely within the 460-acre site." The superintendent also commented that "by the very nature of the historic fabric, largely adobe along with wood and stone, the primary resource is extremely fragile and subject to deterioration from natural and human causes." McChristian anticipated that Fort Davis would welcome "approximately 95,000 visitors during the target year [1982]," and suggested that he and his staff would keep open as many facilities as possible without new personnel. This meant that little if any work could be conducted on historical research or artifact cataloguing, which McChristian estimated at 30,000 items. [9]

The regional office's concern over Fort Davis' ability to meet the demands of visitors prompted a visit to the park in August 1981 by Joseph Sanchez, chief of the SWR division of interpretation and visitor services. Sanchez had worked for one month at the park in early 1980 as its acting superintendent, receiving high praise from the staff for his "keen interest in better cultural resource management and historical accuracy," the latter including his advice on "the revision of the park brochure so that it better reflects the role of the Black troops at Fort Davis." Sanchez, who in the late 1980s would direct the NPS-funded Spanish Colonial Research Center at the University of New Mexico, noted upon his arrival at the park that "Fort Davis is exceptionally and professionally run." He credited the staff with being "especially attentive to visitors," and saw them presenting "a positive image for the National Park Service." Sanchez reported that better access to the refurbished quarters could be provided to the handicapped (a situation that Superintendent McChristian agreed to correct), and then closed by commenting upon the problems of the location of the visitors center in the barracks building north of the administrative offices. "Because the administrative center is the building visitors approach first and often enter," said Sanchez, "it occurs to park management that the circulation pattern to the museum is illogical and confusing." The staff discussed with him the reversal of facilities "to provide a safe emergency exit for visitors to the museum which currently has no rear exit." In addition, "the electrical system in the museum is near the entry way and itself would become affected . . . if something would go wrong." Reversing the order of visitor and administrative facilities would obviate the phenomenon, said Sanchez, where "confused visitors approach the Superintendent's office first." [10]

One feature of Fort Davis' interpretive work that contributed to the glowing report of Joseph Sanchez was the dedication service for the Commanding Officer's Quarters. Some 400 guests arrived at the park on the morning of May 16, 1981, to join with NPS personnel from the Southwest Region, the Denver Service Center, and the Harpers Ferry Center. The COQ had been a favorite of local residents; a tie strengthened by the presence in the area of two of Benjamin Grierson's sons in the community for many years after the closing of the fort. The public speakers included Bruce Dinges, acting editor of the publication, Arizona and the West, whose specialty was the life of General Grierson, and Robert M. Utley, recently retired as assistant NPS director for park historic preservation (as well as deputy executive director for the President's Advisory Council on Historic Preservation). Utley offered the keynote address on "Fort Davis' role in westward expansion;" a subject that he had championed two decades earlier in the initiative to create the park. [11]

Doug McChristian's first two years as Fort Davis' superintendent had a salutary effect upon visitation, as patrons appreciated the ambition of the park staff and its willingness to overcome obstacles. McChristian's second year saw an 11 percent increase in visitor totals, which he attributed to the "stabilization of gasoline prices, increased attention on the Davis Mountains area due to articles in leisure magazines, and increase in population centers such as Odessa and Midland, which are experiencing rapid growth as oil producing centers." This volume of visitors also prompted record sales in the SPMA book exhibit, which increased 49 percent over 1980. In return, the Tucson-based SPMA donated over $7,000 for such items as library materials, "a wayside exhibit for the chapel to include information on the Court Martial of Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper," a "five-day training course for interpretation of the Indian Wars enlisted soldier," and to "improve women's living history attire for the site's interpretive program." Special visitation included "ten members of the State of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department," who attended a one-day seminar on living history interpretation. Superintendent McChristian also recognized the growing contribution of the park's volunteers (23), who donated over 1,000 hours as tour guides, living history interpreters at the historic buildings, and as aides in the library and photograph collection. [12]

Emphasis on the story of Fort Davis also drew the attention of scholars, donors, and public and private agencies devoted to the promotion of tourism and travel in the region. Superintendent McChristian became intrigued at the work of Dr. Robert F. Newkirk of the Cooperative Programs Study Unit in the Department of Recreation and Parks at Texas A&M University. Newkirk sought potential research projects for his students at the College Station campus, and the Fort Davis staff was only too eager to oblige. Mary Williams compiled a list of topics that included the history of the Overland Trail, the development of the town of Fort Davis, an administrative history of the park, work on the sub-posts around Fort Davis, and oral histories of descendants of military personnel stationed at the fort. McChristian himself expressed to Newkirk the need for "a historical base map covering the 460-acre site." "Considering the current low emphasis on studies," said the superintendent, "it will probably be some time before funding is available for this project." McChristian also wondered about Newkirk's interest in "a good military and structural history of the First Fort Davis." The superintendent's inquiries of the Texas A&M professor were also stimulated by the suggestion of the regional office in October 1982 that history departments might have graduate students willing to conduct the research and writing that the park service could no longer support. "Perhaps the [regional] Division of History could act as a 'clearing house' for such requests," said McChristian, as "most history related studies seem to get low priorities these days." [13]

The need for this research activity was apparent to Charles McCurdy, SWR's chief of interpretation and visitor services, who came to Fort Davis in July 1982 on the regional office's annual inspection of the park's historical work. McCurdy, who had last spent time at Fort Davis in November 1980, walked with the superintendent and his interpretive chief, John Sutton, through the refurnished COQ, the post commissary, and the hospital. "The park staff," said McCurdy, "has done a nice job in making the hospital accessible through means of a catwalk passing through it and interpreting it by means of small easels that reveal facets of the world of the hospital in the late 1880's." "Park visitors seem to enjoy themselves at the Fort," the regional official noted; a condition that he attributed to the staffs "good training and good reading." Earning special mention from McCurdy was the portrayal of the soldiers, who "made a nice counterpoint to the refurnished buildings that draw so much interest." He did express concern that the 30,000 artifacts, many of which had been unearthed in the 1969 archeological survey, "remain uncatalogued and many need conservation treatment." Superintendent McChristian informed McCurdy that he would convert a maintenance position to a museum technician who could "do maintenance-type chores." Another issue for the regional interpretive chief was that "the [museum] exhibits are due for a change." Robert Utley's design, which had charmed Lady Bird Johnson at the 1966 dedication, now seemed in the 1980s to "convey more of a story about the development of the Fort than the purpose of the Fort and events on the Indian campaign." McCurdy sympathized with the constraints placed upon the staff, and suggested that the regional office provide Fort Davis with "career interpreter training [in] curatorial methods, and interpretive operations management." He could not resist closing with admiration for the location of the park, noting that "the area looked well cared for," and that "altogether, it's a nice experience to spend the day there and see a well run operation." [14]

One comment made by McCurdy that the park took to heart was his call for an "Interpretive Prospectus," which John Sutton drafted in November 1982. Superintendent McChristian asked Edwin C. Bearss, chief historian for the park service, to review Sutton's ideas. Bearss turned to a former park historian at Fort Davis, Ben Levy, then senior historian on Bearss' staff. Levy's remarks, however, left McChristian confused about their endeavors to define the park's standing in the NPS. Levy commended Sutton for his "well intentioned" ideas, but reminded the park staff that "these issues . . . need to be addressed against the backdrop of history and the reality of policies and costs." The NPS senior historian criticized what he called "the inexorable development from stabilization through rehab [rehabilitation], restoration, reconstruction, and refurnishing even though more limited objectives were the stated intention originally." Levy disliked the fact that "stabilization and restoration" had become "a cloak for more expansive ends," and he stated: "A halt should be called once and for all to the refurnishing objective." He called it "contrary to the policy and the exception that it is needed for interpretive purposes is not justified." As for the vaunted efforts to refurnish the officers' quarters at Fort Davis, Levy saw these as "essentially conjectural." "There are already questionable furnishings installed" at the park, and others concurred in his judgment. "I say let's call a halt and go back to the original intention of preserving the fort essentially through minimum protective measures," wrote Levy. The discussion about the visitor center/administrative offices location prompted Levy to remark: "I too, recognized the foolishness of placing the Offices in the south end of HB-20 and the Museum in the north end." At the same time, Levy disagreed with park staff that the "wordiness" of the museum's label copy alienated visitors. "My observation," reported the senior NPS historian, "was that the adults found every word interesting and followed the story line in an unhurried fashion." He found more irritating the park service's recent shift to "so-called open museums [a reference to the technique of displaying artifacts in open space, rather than in some pattern for visitors to follow]," with their "unacceptable visitor confusion." Levy instead called upon Fort Davis to "refurbish the existing museum," move it to the south wing, and "utilize another area for the innovative display." [15]

When Superintendent McChristian contemplated Fort Davis' achievements for 1982, high on his list were ideas for meeting the criticisms of Ben Levy and others about interpretive programs and facility enhancement. He took great pride in the fact that the park had hired its first black seasonal, James Montgomery of nearby Pecos. Montgomery majored in social studies at Sul Ross, and offered Fort Davis someone who could "interpret to park visitors the lifestyles and history of Black soldiers," either through "a barracks scene or a cavalry program with horse and Cavalry field equipment." More space was devoted in the post hospital to telling the story of health care on the nineteenth-century frontier. This helped McChristian when he brought to the park in May some 31 interpreters from around the region to participate in his Indian Wars camp of instruction. Attendees came from several NPS military parks, the Texas state parks system (Fort Richardson), the New Mexico state parks of Forts Selden and Sumner, and the Wyoming state parks system (Fort Bridger). The Institute of Texan Cultures in San Antonio also sent personnel, as did Fort Concho in San Angelo. McChristian made special mention of the participation of Fort Davis staff in the April centennial parade of the community of Alpine, wherein three staff members and two volunteers rode horseback the 35 miles from the park to the Brewster County seat "as if they were in the field with the frontier Army." Six staff members and one volunteer also traveled in June to San Angelo to join the annual Fort Concho fiesta. All these activities demonstrated the commitment of Fort Davis to keeping the story of the western military alive, and contributed to another good year of attendance, with a five percent increase (75,056). In like manner, these visitors patronized the SPMA book exhibit handsomely, resulting in an 18 percent rise in book sales. The only cautionary note about visitation in 1982 was the decline of Mexican visitors, which McChristian believed resulted from "the devaluation of the Mexican peso." [16]

By 1983, the park staff had realized, as had the NPS in general, that there would be little new money for continued expansion of the legislative mandate that Congress had given to Fort Davis. The national economy had slumped in the winter of 1982-1983 to its lowest point since World War II, and unemployment stood at its highest level since the depths of the Great Depression (nearly 11 percent). Thus the park service began serious discussions about solicitation of private funds to improve the quality of NPS programs and units. Fort Davis already had a private organization that had assisted in the creation of the park two decades earlier (the Fort Davis Historical Society). Unfortunately, as Doug McChristian would recall in 1994, the society "had become more social than advocates for Fort Davis." The group was aging, and few younger people joined. Thus McChristian decided in 1983 to create a new entity, the "Friends of Fort Davis." Their first task, the superintendent determined, would be to seek private funds to restore HB-2 1, the barracks building to the north of the museum/visitors center. McChristian had an estimate made in October 1982 of the cost of restoration (($176,000) and refurnishing ($30,000-40,000). He predicted that such an endeavor would rank low in priority with the NPS, but that a private campaign would "allow the people of West Texas and other interested parties a chance to have a personal hand in developing Fort Davis." McChristian further predicted in January 1983 that such a foundation "could very well turn into a long-term association that could provide financial support for a variety of activities at the Site, particularly by providing financial aid to continue living history programs here." [17]

The irony of McChristian's decision was that the quest for private funding of a public historic site energized the park in ways not seen since the early 1960s. By selecting the enlisted men's barracks as the target of rehabilitation, and by embracing the story of black troopers as never before, Fort Davis once again gained national attention for its innovative ideas and methods of interpretation. This in turn contributed to new monies (both public and private) for restoration and maintenance; all to be linked to the tradition of park service standards and procedures for hiring, design and construction, and visitor services. The synergy of staff commitment, funding, scholarly attention, and visitors' patronage, joined to give the park a new lease on life and validate the efforts of the park planners to make Fort Davis a showcase of western military history.

Figure 43. Restored Enlisted Men's Barracks

(Late 1980s).

Courtesy Fort Davis NHS.

Figure 44. Interior of estored Enlisted

Men's Barracks (ate 1980).

Courtesy Fort Davis NHS.

The first step in moving the park towards McChristian's goal was selection of members of the "Friends" group. The superintendent realized that he needed a mixture of local activists and nationally prominent figures to lend legitimacy and lustre to the pursuits of the board. Local residents who accepted McChristian's offer of membership were rancher Pansy Espy, descendant of one of the first ranching families in the Davis Mountains (who also agreed to serve as treasurer); Donna Smith of Ft. Davis; Thomas Bruner of Midland, vice president and trust officer of that community's Texas American Bank; and Bob Dillard, editor of the Alpine Avalanche and the first president of the board. Joining them from other parts of the country were Dr. John Langellier, curator of the Army Museum at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; Sara D. Jackson, employee of the National Historic Preservation and Records Commission in Washington (a branch of the National Archives and Records Administration [NARA]); William Leckie, professor of history at the University of Toledo and the author of Buffalo Soldiers; and Robert Utley, now a free-lance writer of historical works living in Santa Fe with his wife, Southwest Region chief historian Melody Webb. Superintendent McChristian informed each board member from out of town that they should expect to meet at least once per year in Fort Davis, and that they would be asked to identify pertinent funding sources for a $250,000 restoration and refurnishing project. An example of the scope of the work expected from the board came in McChristian's letter to Thomas Bruner, wherein he informed the Midland banker that the barracks project had been part of the original master plan, drafted 20 years earlier. He also told Bruner that "quite honestly, Fort Davis offers the only opportunity for the black Regulars to be represented in the National Park System." Other frontier posts were preserved within the NPS, but McChristian made clear that the racial character of military service at Fort Davis would be central to any proposal to private funding agencies. [18]

Before the board came to Fort Davis for their first gathering, the superintendent asked the Denver Service Center to review the original plans for barracks restoration. A DSC staff member came to the post on June 9,1983, and offered both technical advice and guidance on fundraising. In a letter to the board members soon thereafter, McChristian said that "by using private funds [the NPS] can drastically reduce the usual amount of overhead and can reduce the amount even further depending on how much of the preparatory work we might accomplish with the park maintenance staff, day labor, volunteers, and by contribution." Thus the 1978 estimate that restoration would require $176,900 (without furnishings) "may come out closer to $100,000." McChristian himself calculated the furnishing budget to be some $25,000, and had initiated conversations with donors and replica manufacturers to receive special gifts and rates because of the nature of the barracks project. The superintendent wanted the board to meet as soon as possible, perhaps during the September meeting at Fort Davis of the Order of the Indian Wars, to which several board members belonged. Among his reasons for the accelerated pace of work were the need to establish tax-exempt status, to plan strategy, and to avoid the inevitable delays (which McChristian called the "ever-present red tape") connected to "complex government accounting procedures." [19]

To further the efforts of the Friends board, McChristian and the park staff in the spring and summer of 1983 pursued other avenues of support for the historical mission of Fort Davis. Most prominent among these was the release of a contract for $392,000 to Roof Builders, Inc., of El Paso to reshingle 20 of the historic structures, redeck all porches on Officers Row, and other work on the walkways, landings and porches of the row. This money came from the "Park Rehabilitation and Improvement Program," (PRIP), which also permitted Fort Davis to hire a temporary carpenter to assist the maintenance staff. In the area of historic interpretation, the park installed a new "photo-metal" wayside exhibit at the post chapel to "interpret the multifunctional chapel as well as commemorate the court-martial trial of 2nd Lieutenant Henry 0. Flipper." Funds for this activity came from the SPMA. A third area of interest that summer for the staff was planning for a new "park headquarters." They wanted "a more formal reception area," "separate sound-proofed offices for key personnel," "a staff room large enough to accommodate meetings and training activities," "a larger and more isolated library," "a separate, yet convenient, room for xeroxing and office supplies," and "an office for the maintenance foreman." Finally, the park began to address the backlog of unaccessioned artifacts, which would increase dramatically once excavation began on the barracks, by hiring as a museum technician Judith M. Hitzman, most recently a staff member of the NPS' Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Montana. McChristian directed Hitzman to bring order to the cataloguing process, and to train cooperative education students for collections work, as well as to instruct volunteers in "historic housekeeping techniques." [20]

When the Friends group assembled at the park on September 14, 1983, they faced both a challenge and an opportunity. In order to commence their own task of fundraising, the board needed specifications and plans drawn by the Denver Service Center, and quickly. Unfortunately, the park could commit no funds to this endeavor. Thus Superintendent McChristian suggested that they raise the sum of $10,000 immediately to pay the DSC to send staff to Fort Davis and prepare the planning documents. The board authorized the solicitation of memberships (at $2 per year or $25 for life members), while the staff placed a donation box in the visitors center. By year's end the Friends had collected some $4,000 toward the DSC planning. McChristian asked his staff to conduct as much maintenance work at the barracks as possible to reduce the length of time and the amount of money needed to begin rehabilitation. The most critical feature of the early phase of barracks work, however, was the use of an archeological consultant to identify the existing historic resources. The DSC had no one available at short notice to send to Fort Davis, but suggested that McChristian seek a contractor to perform the survey work. Fortunately there resided in the town of Fort Davis a married couple, Ellen and Dr. J. Charles Kelley, who had moved to the Davis Mountains after retiring from Southern Illinois University (she as curator of collections for the university museum for 23 years; he as a professor of archeology for 25 years). Each summer the Kelleys had maintained a home in the Davis Mountains, and conducted archeological digs in the Big Bend area and in Mexico. By agreeing to oversee the survey without compensation, and by utilizing a team of volunteers "Junior Historians" from Alpine High School, the Kelleys managed to complete the digging within the space of three months in the winter and spring of 1984, saving the Friends and the park some $20,000 in the process. [21]

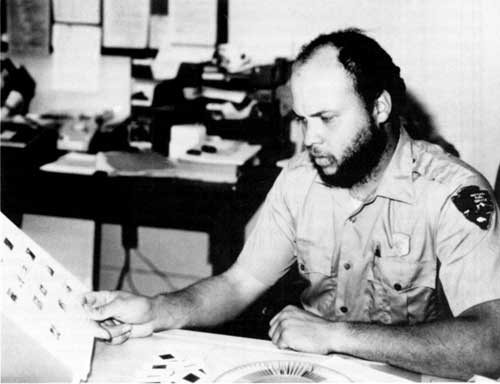

Whether it was by coincidence or by design, the escalating pace of work at Fort Davis, especially its emphasis on the story of the black soldier, brought to the park in November 1983 William "Bill" Gwaltney as park technician (with primary duties as a ranger and law enforcement officer). Gwaltney was one of the few black NPS employees with an interest in the history of the West; a circumstance that he attributed in a 1994 interview to his family's heritage of service in the armed forces (including a grandfather who had been one of the famed "Buffalo Soldiers" of the late nineteenth-century). Gwaltney would spend three years at Fort Davis, in which time the park generated much information and publicity about the place of black troopers in the service of their country. When he first arrived in Fort Davis, Gwaltney soon recognized both the "invisibility" of the black soldier in the minds of community members, as well as the ambivalence of the staff towards interpreting the black experience with white personnel. Gwaltney decided to "normalize the dialogue" about black soldiers, realizing that to most visitors the park symbolized what he called "Texas nationalism" rather than the competing forces of discrimination and opportunity that military service implied. [22]

Throughout the spring and summer of 1984, the Fort Davis team of Bill Gwaltney, Mary Williams, Doug McChristian, and supervisory ranger John Sutton addressed all manner of historical and cultural issues at the park. The superintendent prepared a furnishings plan for the barracks, and coordinated the fundraising strategies of the Friends board. McChristian also learned of new initiatives in documentary filmmaking about the Buffalo Soldiers, especially one promoted by WHNM, the public television station of predominantly black Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Figure 45. Park Technician William "Bill"

Gwaltney (1980s).

Courtesy Fort Davis NHS.

The park wished to update its 1960s-vintage orientation film to reflect the sensibilities of the civil rights era, and WHNM's "The Different Drummer" seemed a logical choice to replace the existing video. Mary Williams continued to research and develop women's history activities for the park, and Bill Gwaltney approached a series of scholarly and popular journals and magazines to interest them in the black soldier story. Gwaltney and McChristian also corresponded with other NPS sites with black history themes to encourage them to incorporate western history in their slide shows and displays on black America. [23]

These initiatives led McChristian, Gwaltney and the Friends group to focus more closely on promotion of the black perspective on Fort Davis history in their applications to private funding agencies for the barracks restoration project. The most noteworthy of these efforts came with the Meadows Foundation of Dallas. Pansy Espy remembered how the Friends sat down with directories of philanthropic organizations nationwide, and members Bob Dillard, Tom Bruner, and herself wrote over 130 applications. The Meadows Foundation, created in 1948 by Algur H. Meadows, the founder of the General American Oil Company of Texas, had never worked before with a federal agency on a grant proposal, but they found fascinating the strength of the black heritage at Fort Davis. McChristian, Gwaltney, and Sara Jackson of the National Archives thus travelled to Dallas in July 1984 to plead their case to the Meadows board, asking for $50,000 to defray the expenses of the barracks restoration. The seriousness of the Friends' message, and the reputation of their board nationally, led the Meadows Foundation to grant their request in October of that year. The $50,000, plus some $10,500 raised that summer by the Friends at the park, helped attract other monies as well: $3,000 from the Burkitt Foundation, $2,500 from donations at the visitors center, and $35,000 in "in-kind" (non-cash) services provided by the Southwest Region's "Cultural Resources Preservation Crew." One distinctive feature of fundraising was the institution of the Labor Day weekend "Barracks Restoration Festival," which in 1984 contributed $6,000 to the private donations to the project. Overall, by January 1985, Superintendent McChristian could claim that the Friends had raised $101,000 (the total cost of barracks restoration), with the furnishings plan next for the Friends to consider. [24]

While it would have been tempting to focus all of the park's energies on the barracks restoration project, Superintendent McChristian also faced issues of management that were no less crucial to the success of his staff. Early in 1984, the superintendent asked the Southwest Region to assist him in securing funding for an historic base map and "General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan [GMP/DCP]." This latter request emanated from news that the Denver Service Center had prepared "Historic Preservation Guides" for the park that McChristian believed could serve as "the foundation of a Maintenance Management Program," which in turn would "better enable management to plan and program cyclic maintenance needs." The superintendent continued to monitor claims that Holloman AFB wished to increase its supersonic flights over the Valentine area. McChristian reported to his superiors in Santa Fe that "the environmental impact statement issued by the Air Force was hotly contested by local groups, particularly the Council for the Preservation of the Last Frontier."

Encroachments upon the air space of the park were matched by fears that Mrs. J.A. Hanchey of Lake Charles, Louisiana, would sell her tract of land adjacent to the site's south boundary, near the base of Sleeping Lion Mountain. McChristian noted that "various superintendents, past and present, have expressed concern over the development potential of this tract." The property, less than five acres in all, "lies only a few yards from the parking lot and within a few feet of the site of the Post Trader's Store," "virtually on the front doorstep of the Site." McChristian entered into conversations with Mrs. Hanchey, whom he reported "concurs completely with management's concerns and said that she would be more than happy to work with the Service in any way to see the boundary protected." [25]

These latter two issues dramatized the realities of management at Fort Davis, especially its inability to halt the intrusions of the military or the private sector because of the limited financial resources of the NPS, and the power of the armed forces in the years of the Reagan-era defense buildup. In early 1985, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) announced that it would, at the insistence of U.S. Representative Ronald Coleman, an El Paso Democrat, and U.S. Senator Jeff Bingaman, a New Mexico Democrat, investigate the report that the environmental impact statement released by Holloman AFB would include as many as 750 sonic booms per month over the Davis Mountains. New Mexicans were outraged that the Air Force also had targeted the Gila Wilderness area known as the "Reserve MOA [Military Operations Area]," and that both the Valentine MOA and Reserve would undergo an increase of overflights of 1,000 percent (or 14,000 flights per year). The level of protest did halt the overflight expansion, but the Air Force's insistence that it needed ever more open space for testing rankled Superintendent McChristian, much as it did his colleague at White Sands National Monument, Donald Harper, who had the air base as a neighbor in the Tularosa basin of southern New Mexico. [26]

At the close of his fourth year of service as Fort Davis' superintendent, Doug McChristian had much to consider when the NPS asked him to comment upon the topic: "Where the National Park Service is Going." Buoyed by his experiences with private fundraising, yet burdened by limited operating budgets, McChristian wrote in November 1984: "I cannot escape the feeling that the Park Service is losing something, a spark or optimism that it once had." This McChristian blamed on the NPS' "becoming increasingly pre-occupied with things like regulatory compliance, 'special emphasis' programs, needless paperwork, and personnel problems." While this could be nothing more than "an inescapable syndrome inherent with being a Federal agency," yet McChristian hoped that the NPS "and its people" could be "reoriented, redirected to the traditions upon which the Park Service is founded - resources and visitors." The 15-year veteran of NPS employment conceded that "the agency must grow with and adapt to a changing and increasingly complex world." Nonetheless, said McChristian, "we should make every effort to hold fast to our principles," which he defined as "the dedication, attitudes, and ability of our employees." McChristian worried particularly about the impact of the expanded paperwork on small parks like Fort Davis, and the need for "greater understanding and cooperation between central office staff and field personnel." The superintendent had "worked on both sides of the fence," and had concluded about the regional office: "I know how they can hinder our ability to get the job done." [27]

The Southwest Region of the NPS had to recognize the sincerity of McChristian's words, given the success of his park in raising funds for the barracks restoration. Thus deputy regional director Donald Dayton, himself a former superintendent at parks like White Sands and Carlsbad Caverns, cited Fort Davis in January 1985 as "one of the few consistently well run parks in the Region." "Such compliments don't come down the line very often," McChristian told his staff, and he thanked them for their contributions to the park's recognition. "The credit for this," said the Fort Davis superintendent, "falls to each and everyone of you for doing your utmost in the big things as well as the countless details you may feel go unnoticed and unappreciated." McChristian long had felt that Fort Davis was "an above average operation," and the staff needed to know the thoughts of the regional office as it moved towards the second half of the 1980s. [28]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foda/adhi/adhi7a.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2002