|

FORT DAVIS

Administrative History |

|

Chapter Five:

Encounters with the Ghosts of Old Fort Davis: Interpretation and Resource Management, 1966-1980 (continued)

Smith divided his time between managing the affairs of Fort Davis and commuting the 220 miles by car to the west Texas city of El Paso. His work at an historic site that had undergone substantial construction excited Smith with the possibility (one that few NPS superintendents ever had) to shape the future of a second unit of the park service. Determined also to fulfill LBJ's dream of a new order in ethnic relations along the U.S.-Mexican border, Smith spent a good deal of time acquainting himself with the distinctive ecology, economics, and cultural complexity of the larger Rio Grande basin. Among these efforts was his request to his superiors to fund a Spanish language training course for himself at the NPS' Albright Training Center at the Grand Canyon, and the use of Fort Davis' Hispanic employees at Chamizal. He would take his chief of maintenance, Pablo Bencomo, with him on occasion to El Paso, as Smith admired his skills at construction and personnel management. Eventually, Smith asked Bencomo to work full-time at Chamizal, offering him a higher pay grade at the much-better funded urban park. Bencomo, however, declined the invitation, as he planned to retire one day and live in his hometown of Fort Davis. Smith also brought to Chamizal Richard Razo, a former NYC staffer of the 1960s at Fort Davis, to serve as ranger. In addition, he linked programs of films and education between the two parks, and at times utilized Fort Davis funds for Chamizal purposes when appropriations for the latter were delayed. [20]

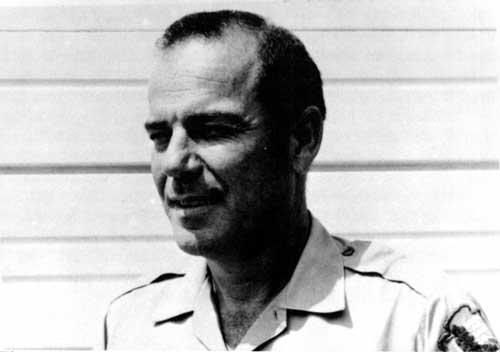

Figure 41. Superintendent Derek

Hambly.

Courtesy Aggie Hambly.

By dividing his time between Fort Davis and El Paso, Frank Smith could not devote all of his attention to either site; a situation that the Southwest Region corrected in August 1971 by transferring Derek O. Hambly from Padre Island National Seashore to the old military post. His background as a naturalist differed from Smith's work in museums and historical interpretation. For that reason Hambly deferred to his staffs expertise in history, which proved fortuitous because of the presence in the early and mid-1970s of several ranger-historians: Mary Williams, Nick Bleser, and Doug McChristian. Williams first came to Fort Davis in 1969 as a seasonal hire, with a master's degree in colonial U.S. history from the University of Connecticut. Bleser would serve as the "supervisory park ranger" until 1972, replaced by McChristian, the recipient of a history degree from Fort Hays State College in western Kansas. Bleser had developed the first "living history" program at Fort Davis, and wanted someone dedicated to this form of historical representation that had become popular in the 1960s. [21]

Superintendent Hambly faced the same issues of budget reductions, hiring practices, and community relations that had bedeviled Frank Smith in the years after the park dedication. His supervisory park ranger, Nick Bleser, set the tone for the 1970s when he wrote in January 1972 to James White of Phoenix, Arizona, who sought information about employment in the park service. Calling the situation "bleak," Bleser told White that "we have recently been ordered to cut back on approximately 500 permanent positions within the Service." This extended to promotions, which were "pretty much at a standstill." As for applicants for permanent positions, "[those] who have passed the Federal Service Examination with scores of 95 or better number in the thousands," while "we have already received more applications for summer employment during the past week than we received in several months of last year." Continued efforts by the administration of President Richard Nixon to reduce what was then considered "rampant" inflation (five percent) and federal spending led Bleser to conclude: "We have nothing here, and the whole outlook throughout the National Park System is rather grim." [22]

Because of the pressure to find employment in the face of continuing budget cuts, even the federally sponsored youth and minority programs came under close scrutiny. Alex Olivas wrote to Representative Richard White in July 1972, asking that his son Danny be hired at Fort Davis as a summer seasonal. It seemed that Danny Olivas had thought he would work at the post, only to discover that he was assigned to the nearby Davis Mountains State Park. In an interesting twist on race relations in the Trans-Pecos region, Alex Olivas charged that Hambly had hired Mexican nationals rather than his native-born son. "We hire our youths," said Bleser, "on an unbiased, combined balance of ability, interest and economic need." The youths whom Alex Olivas had challenged were American citizens of native-born Mexican parents. "We wish it were possible," Bleser wrote to White, "to hire every kid in town full-time permanently." The park informed the El Paso congressman that "we invite and welcome criticism," and believed that the Olivas inquiry demonstrated that "this must be a successful program and a good place to work if people are fighting to get in." [23]

While the youth programs appeared healthy at Fort Davis, Superintendent Hambly had fewer kind words for the change in status of rangers undertaken by the NPS in light of budget cuts. In September 1972, Hambly wrote disparagingly to the Southwest Region of the decision made in Washington to shift many positions from professional to technical status. This permitted the NPS to hire individuals with lesser educational and employment credentials, and to pay them reduced salaries. Fort Davis also could not permit the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) in 1972 to maintain a camp on the grounds. "I would not want to commit my staff to this program," Hambly informed the SWR director, "unless we have assurances that the money is available for the camp construction or improvement." Then in March 1973, the superintendent learned that the U.S. Department of Labor would no longer fund the NYC program for the park service. Hambly did note that the NYC would try to continue its recruitment of American Indian youth. While his park could use employees with such ethnicity, he realized that the heavily Hispanic population of the Fort Davis area meant that "the insertion of more manpower into the area from outside sources would not be in the best interests of the local program." [24]

While Derek Hambly could not solve the problem of declining revenues for summer employment, he did receive good news about local relations in April 1973, when Robert Utley nominated Barry Scobee for the "National Park Service Honorary Park Ranger Award." As the NPS champion of creating Fort Davis National Historic Site, Utley commended the former justice of the peace "for encouraging tourism into the region and awakening public awareness of, in particular, the national historical significance of Fort Davis." "Mr. Scobee's remarkable knowledge of history," Utley wrote, "gathered during more than a half century of research, has contributed immeasurably to our understanding of the history of both Fort Davis and Big Bend National Park." Utley, who wrote a good deal about the old frontier military post himself, further praised Scobee: "Without his knowledge and assistance--and his eagerness to answer any call for advice or information--our grasp of the region's history would be much weaker." Scobee's "contributions to the Service, to the people of the United States, and to the cause of historic preservation," said the NPS director of the Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, meant that the longtime historian of the Davis mountains would be recognized by the agency that had benefitted from his 40 years of advocacy. [25]

Robert Utley's nomination of Judge Scobee found a receptive ear in Washington, where the NPS agreed to honor the "father" of Fort Davis with its honorary ranger award. Scobee, whose relationship with Bob Utley had been strained by the latter's skepticism over the Indian Emily legend, nonetheless thanked the former SWR regional historian for his "fine, tiptop, superb, and superexcellent recommendation for me." The judge considered it "an honor indeed, and a flower in my lapel for my many remaining years--I'm only 88." Scobee, who had since moved to a nursing home in Kerrville, Texas, could take pride in the high-level NPS recognition of his efforts. "Your labor of a long lifetime," said Utley in a letter to Scobee, "has borne rich fruit in Fort Davis National Historic Site and it is only proper that your achievements have been acknowledged." Four years later, upon the announcement of Scobee's death (March 18, 1977) at the age of 91, Superintendent Hambly spoke for many within and outside the park service when he wrote to Frank Mentzer, public affairs officer for the Southwest Region: "The town of Fort Davis, and those staff members of Fort Davis National Historic Site that were privileged to know him, will always remember Mr. Scobee and his contributions to the historical heritage of this area and to the people of the United States of America." [26]

Where Superintendent Hambly had nothing but praise for Judge Scobee, his attitude towards the conditions of employment changed as the decade of the 1970s advanced. For his fulltime staff, Hambly complained about the lack of funds for travel, housing, and failure of the NPS to maintain cost-of-living standards. For the youth programs, however, Hambly began to echo the growing conservatism in the nation and within the NPS about continued reliance upon these "Great Society" social welfare programs. "For the last three years," Hambly wrote to the SWR director in July 1974, "I have been utilizing the subject programs that I inherited from the former administration of this area." Frank Smith's successor conceded that "we have received a significant amount of relatively cheap benefits from the [youth] program," but Hambly was "not . . . at all satisfied that the overall benefits are justifying the time and energy it takes to administer the program." [27]

What had triggered the superintendent's retreat from Smith's commitment to minority hiring was his discontent with the current group: "Youngsters that were barely fourteen years of age in some cases." Such employees were "too young to deal with the public effectively," said Hambly, and they were also "too juvenile to entrust with other chores such as cleaning and caring for artifacts." Even when assigned to the information desk, the superintendent complained, "it was necessary to have an older person with them at all times." Compounding Hambly's personnel problems was the fact that "the YOSSC program was supposed to have been primarily for those who were interested in going on to college." Over time the "financial limitations of the program" had caused Hambly to "pick them [the student hires] primarily from former NYC ranks." This created the belief in town that "we are expected to supply jobs automatically," resulting in "a lack of incentive and the attitude that the positions are a right rather than a privilege." From this, said Hambly, came "a degree of irresponsibility and idleness." The superintendent's corrective was "phasing out the [NYC] program in favor of hiring college students who we believe to be more responsible and more able to relate to the public." These he identified as students "from the local college [Sul Ross] in conjunction with the recently completed contract there." [28]

In the summer of 1974 Superintendent Hambly assessed the value of recruiting ethnic minorities in any capacity at his park. "While black history is a part of the total story at Ft. Davis," he reported to the SWR regional personnel officer, "it is only a part and not the whole ball of wax." Hambly had asked Sul Ross placement officials to "look for at least one black student to work in the cooperative education program." Whether Sul Ross had any such students, the superintendent informed his regional superiors: "I am not going out of my way to hire black students just because black troops were at the Fort for a period of time." Reflecting the national mood of discontent with the liberal demands of the preceding decade, Hambly further stated: "Neither am I going out of my way to hire chicanos or anglos or any other ethnic group." Rejecting the argumentation of his predecessor, Hambly contended that "we have enough worthy students of all denominations here to do the job we need to do." Thus he saw little value in making "a special effort to recruit just black students other than the effort we have already mentioned." [29]

As for his NPS-funded employees, Hambly spent a good portion of his tenure in the 1970s battling to resist the slide in working conditions and morale that eventually prompted the systemwide report entitled, State of the Parks-1980. Pay raises were few and far between, and housing in the Fort Davis area worsened as the Trans-Pecos region witnessed the oil boom that occurred in response to the quintupling of crude oil prices during the twin "embargoes" and "energy crises" of 1973 and 1979. The region had what was considered the finest crude oil in the nation (West Texas Intermediate Sweet Crude) that rivalled the quality of the Persian Gulf Arab nations that forced energy prices to rise exponentially. The situation for housing and other social services throughout west Texas grew more competitive with the high salaries paid to white collar and production workers alike, and in 1976 the NPS sent to the Fort Davis-Big Bend area a team of observers led by former Fort Davis superintendent Michael Becker to assess the crisis of living costs. Hambly took exception to Becker's decision to use housing prices and wages from Fort Stockton as the baseline data for his study, as he preferred nearby Marfa as more reflective of the situation in Fort Davis. The superintendent considered the difference crucial, as he would have to seek in the next budget the additional funds to match these higher costs of living; a situation that might jeopardize his requests for monies to correct other pressing problems of maintenance and operations. [30]

In matters of community relations, Superintendent Hambly's concerns about offending the Anglo majority in the region with minority hiring did him little good when charged by county commissioners with conspiring with federal officials to close the town garbage dump. For the first dozen years of its existence, the park had taken its trash to the open dump on the historic site property, where it was incinerated. In March 1973, the Southwest Region learned from the Texas Air Control Board that NPS use of such dumps at Fort Davis and Lake Meredith were not in compliance with federal and state clean-air regulations. Hambly became upset when he learned that other state agencies in the area, as well as local citizens, continued to use the dump, when the NPS had to pay the cost of transporting its refuse the sixty-five mile roundtrip to Alpine. The superintendent complained to local and state officials of this oversight, leading the Texas Air Control Board in the spring of 1975 to close the Fort Davis dump to all users. This led the county commissioners' court in July to call Hambly before them to inform him of their intent "to write a letter to my supervisor asking that I be removed as Superintendent." Hambly went before County Judge Wanda Adams with documents from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Texas Air Control Board explaining the problem. "Evidently," Hambly told the SWR director, "the Commissioner[s] are locked into the idea that I am meddling in affairs that are of no concern to me." They wanted to know "by what right I had to complain about the dump," and whether the superintendent "knew what the cost would be to relocate the dump." Hambly managed to elicit from his accusers the concession that "they had not explored that facet [funding a new dump] either and one commissioner stated that they had been aware of the problem for five years." The superintendent then "pointed out that personal attacks on me would not alleviate the problem, that there were other avenues to examine, and that such organizations as the newly formed Fort Davis Chamber of Commerce and the West Texas Council of Governments were two possible sources of ideas." [31]

As if the garbage dump issue were not enough to tax Hambly's patience, the U.S. Air Force in March 1978 sent to Fort Davis two officers from Holloman Air Force Base in southern New Mexico to "gather preliminary data in preparation for a possible impact statement concerning supersonic training flights over portions of west Texas." The Air Force itself had not extended the courtesy of informing Hambly of its intentions, as the superintendent had to learn of the potential overflight problem from members of the Fort Davis chamber of commerce and the McDonald Observatory. Thus Hambly had to write to Brigadier General William Strand of Holloman that "many of these buildings are fragile and could be affected by shock waves from sonic booms." The military had already established a pattern of such flights over the NPS' White Sands National Monument, some 300 miles northwest in the Tularosa basin of New Mexico. Hambly thus sought to avoid the difficulties that White Sands had earlier experienced with its Air Force neighbors during the height of training for the war in Vietnam. Said Hambly to Strand: "This office must do everything in its power to avoid any possibility of damage to these irreplaceable structures of national importance." The Fort Davis superintendent needed from Strand "assurance that the type of training area discussed by your officers during their visit would be far enough from Fort Davis National Historic Site so that no chance of damage from sonic shock waves would be possible." [32]

The best that the Air Force could promise Derek Hambly was to move its training area some 15.5 miles away from Fort Davis. The military in the years after Vietnam had begun to look for larger sections of land in which to prepare soldiers for war, especially with the focus upon air defense that required vast stretches of open space for the high-technology aircraft being designed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Hambly told his superiors in Santa Fe that "I know that a sonic boom can travel more than fifteen miles under the proper conditions." He had learned that "there is some indication that an excess of 150 sonic booms per day would be striking the ground," and that "there might be an overwhelming opposition to the noise that these training operations would create." Fearing "noise pollution" as well as "damaging vibration" from the training program, Hambly again asked the Southwest Region: "Since the National Park Service has had experience with sonic noise at other areas, perhaps such expertise will be able to determine if 15.5 statute miles is enough space" to protect his park from Air Force intrusion. [33]

Hambly's efforts to protect his historic resource consumed much of his time in the last years of his superintendency (1978-1979). In May 1979, Colonel Richard L. Meyer, commander of Holloman AFB, wrote to Wayne Cane, acting SWR director, to inform him of the continued planning for what the Air Force called the "Valentine Military Operations Area." Meyer's staff had prepared a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on the program, and had agreed to "address specific Air Force actions that have been taken to preclude a sonic boom impact upon the town of Fort Davis and the National Historic Site." This did little to satisfy concerned local residents, who approached Representative Richard White at the July 4 celebration at Fort Davis with calls to restrict the Air Force's reach into the Davis Mountains. White surprised his constituents by saying that "he did not think he could stop the proposal, nor was he inclined to do so," citing as his rationale to the Alpine Avalanche his belief "in the defense of America, and we must all make sacrifices." Instead White advised the Jeff Davis County contingent to "pursue a lawsuit to block the flights." He acknowledged that "the Air Force has refused to honor claims of damages to homes unless residents could document the exact time of day the booms occurred." White did promise to try to get the Air Force to move the flights, but he did not think that alternative sites over the Gulf of Mexico (a long distance from the pilots' home base in southern New Mexico) would appeal to the military. [34]

Derek Hambly would leave Fort Davis in the fall of 1979, still unable to gain from the Air Force any promises of protection. Nor was he able to resolve the conflict with Jeff Davis County about the offending garbage dump. These would be issues left to his successor, William F. Wallace, the superintendent of Capitol Reef National Monument in southeastern Utah, with whom Hambly traded positions. Wallace, who would stay at Fort Davis for less than one year, informed the Santa Fe regional office soon after arrival in west Texas that his major concerns for the future of park included "the possibility of U.S. Air Force overflights in the immediate future," while "the continuation of the routine burning of the local community garbage dump creates an air pollution and odor problem as prevailing winds saturate the entire Fort area during periods when the dump is burned." To this Wallace added the old concern of "developments/construction on private lands immediately to the South of the Fort [that] could create an adverse effect due to the close proximity of the main Fort structures." [35]

Because most of the critical questions of park planning had been addressed by the late 1960s at Fort Davis, it remained for the staff hired by the superintendents to implement ideas fashioned in the heady days of the park's creation. This suited the management styles of Frank Smith and Derek Hambly, as well as the procedures established by the NPS to rely upon qualified personnel to fulfill the mandates of the particular enabling legislation of a park unit. Thus it is instructive to analyze the three major categories of daily life at Fort Davis (facility security and maintenance, historic structure rehabilitation, and visitors services) through the efforts of the employees from 1966-1980. These included, but were not limited to, the work of Pablo Bencomo and his maintenance crew, and the historical research and program development of Benjamin Levy, Mary Williams, and Doug McChristian. The staff had to engage both the idiosyncracies of regional and community perspectives on the park, the dictates of NPS program and policy regulations, and the trends in historical scholarship that sought to realign the western story with that of the "new social" history of the 1960s and 1970s, focusing upon the role of ethnicity, gender, and environment as factors in the development of America's western frontier. How the park service in general, and Fort Davis staff in particular, met these objectives says much about the challenge of national organizations to change themselves, and to speak clearly to local constituencies more enamored of what Michael Kammen aptly referred to as the "mystic chords of memory" that history can provide.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foda/adhi/adhi5a.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2002