|

FORT DAVIS

Administrative History |

|

Chapter Four:

Shaping a Visible Past: The Five-Year Plan of Historic Preservation, 1961-1966

The signing in September 1961 of legislation creating Fort Davis National Historic Site constituted the first half of the journey for revitalization of the abandoned military post. Before Lady Bird Johnson could grace the platform at the dedication ceremonies in 1966, NPS officials and supporters labored for five years to develop strategies for restoration of buildings, hire staff, implement policies and guidelines, and convince the surrounding community of the importance of park service programs to their lives. For Fort Davis, the historic site had not only the backing of many political sponsors, but also the good timing that Michael Kammen found critical to park survival in the 1960s. "Between 1961 and 1979," said the historian of American cultural memory, "the federal government became principal sponsor and custodian of national traditions." Yet within these two decades, "[there] began a process of fiscal and administrative retrenchment that has continued ever since." [1]

Such considerations were on the minds of park service personnel throughout the five years dedicated to the planning and implementation of the $1 million restoration and stabilization program at Fort Davis. They and their local partners in west Texas knew only too well of concerns about the coercive power of the federal government, not to mention its taxes and regulatory demands. The NPS also had to contend with national forces in the first half of the tumultuous decade of the 1960s: race, ethnicity, antiwar sentiment, and growing disaffection with the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, whose support of Fort Davis had made its high level of funding possible. Yet the chance to work on a park that Franklin Smith, superintendent from 1965-1971, called the "last of the old parks," because of its "touch of the romantic," proved spellbinding for NPS officials eager to work on the story of the frontier West and its Indian wars. [2]

Even before the arrival in Fort Davis late in 1962 of the first superintendent, Michael Becker, the Park Service and its parent, the Interior department, learned of the expectations and controversy that the historic site would generate throughout the first thirty five years of its existence. A "Miss Virginia M. Stallings" wrote to the Senate sponsor of the park legislation, Ralph Yarborough, in November 1961 to complain about a rumor that she had heard about waste in the Park Service. Miss Stallings asked the whether NPS planned to "entertain proposals to demolish any of the historic structures comprising Fort Davis." This was in addition to a story that Interior sought to "expend $3,000,000 for a grass growing project in the desert [she did not say where]." John A. Carver, assistant secretary of the Interior, thus had to release the first of many letters of correction to critics of the NPS. Carver informed Senator Yarborough that not only did the Park Service not intend to destroy the buildings at Fort Davis (nor grow grass in the desert), but that "it has been our experience frequently that after the Congress has authorized the establishment of a new unit of the National Park System rumors of various sorts, often unfounded, are circulated." [3]

More thorough was the inquiry of Dale Walton, state editor for the San Angelo Standard-Times, who asked SWR's Erik Reed in March 1962 to provide information about the status of the park. Walton apologized for not knowing more about the plans of the Park Service, and reminded Reed that "we have a prime interest in the fort and the town and would like to get started with stories on work there." Reed sent Walton a copy of Bob Utley's 1960 "area investigation report," and noted that until the NPS purchased the land from Mrs. Jackson, "I cannot give you a precise forecast of future activities at Fort Davis." The regional chief of interpretation did, however, reveal that the park service had asked Congress to include in its fiscal year 1963 budget $395,026, which "would provide for the purchase of the property and for staffing the area with essential personnel." In addition, the SWR could then "launch the first year's work on stabilization and restoration of the historic structures, and begin the construction of roads and trails, visitor center (museum and park headquarters building), employee residences, and utility structures." Construction would be designed and managed by the NPS, but private firms would receive the contracts for the actual work. Reed did not anticipate charging admission fees (one of Walton's queries), as it was not NPS policy to do so "at areas of the size and character of Fort Davis." The regional office, however, "would appreciate receiving copies of any articles [Walton] may write on Fort Davis," and Reed looked forward to working with the San Angelo paper in the promotion of the newest park in west Texas. [4]

Curiosity and confusion about Fort Davis reached the highest levels of the park service that same week in March 1962 when Frank Masland, a member of the Interior Secretary's Advisory Board from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, wrote to his friend "Connie" (Conrad) Wirth, NPS director, about his recent trip to the Davis Mountains. Echoing a sentiment of many easterners, Masland found the area "beautiful," and thought that "they would probably qualify as a National Park." But in his "humble opinion, Old Fort Davis doesn't qualify for anything." As a staunch conservationist, Masland considered the stone and adobe structures to be "a mongrel bunch," and "it would appear that some of them are being lived in." He then criticized the elaborate plans made for Fort Davis: "The lay of the land is such that if with a considerable expenditure of money buildings could be restored and/or stabilized and the place cleaned up, there would, I think, be little visitation and less reason for it." Wirth's friend then suggested that "it would not be simple to lay out a program for visitors," since "the buildings are scattered over too wide an area." Instead Masland hoped "that if there is public pressure for Service acquisition it can be resisted." [5]

The bluntness of Masland's letter required a diplomatic response from the NPS director, who thanked him for his "views" and could "appreciate that in [Fort Davis'] present condition it may not have impressed you favorably." Wirth expected that passage of the 1963 park service appropriation bill "will provide funds for land acquisition there and some money to begin a program of stabilization of the structures and ruins." The director then hoped that Masland would "change your mind about Fort Davis when you see it again . . . after we have had a chance to improve conditions there." Wirth saw in Fort Davis "a long and fascinating history in the story of the southwestern frontier." The park service stood committed to "bring this out in our development," and he took pride in the fact that "the people in Texas are enthusiastic over the prospects." [6]

The long-awaited congressional funding arrived in October 1962, which permitted the NPS to approach Mrs. Jackson with an offer to purchase her property. When Barry Scobee received word of this action, he wrote to Conrad Wirth in December 1962 asking advice about the promise made by the Fort Davis Historical Society (FDHS) to contribute whatever funds it had towards the acquisition of park land. The amount stood at some $5,000, and Scobee wondered if this could be applied to another project since Congress would now meet Mrs. Jackson's quote. What the venerable historian of the Davis Mountains sought was use of the money to publish his manuscript on Fort Davis and the surrounding territory. Wirth considered it "an advantage to have a book on Fort Davis, such as yours, available for the public as soon as possible after the historic site is established." The park service would be several years away from producing its own text on Fort Davis. To that end, Wirth instructed SWR's Bob Utley "to assist [Scobee] in any way possible if you have any questions concerning format or historical procedures in publications." [7]

Appropriation of Fort Davis monies in late 1962 also permitted the park service to advance the work of Bob Utley along two tracks: the development of the historic structures report (so that construction could begin the following spring); and the collection of historic data for use in the new museum and visitors center complex (itself the target of early construction work). Michael Becker remembered how Utley's professionalism influenced the quality of the work. Utley, in Becker's words, was "very thorough," and provided the superintendent much "useful information." Becker had come to the park from his first superintendency at Tumacacori National Monument in Arizona. He had never heard of Fort Davis, but realized soon thereafter that a combination of regional and Texas political interest in the site made it a special place. Becker would later call Fort Davis his "best job in 30 years in the park service," in part because of its high profile and because of the chance to build a park from the ground up. In addition, the lack of new park formation in the 1950s had meant few career moves for park rangers. By 1960, said Becker, 80 percent of rangers had "hit their peak." Fort Davis allowed him to move upward from Tumacacori, and he knew at the time that "few superintendents get that experience [where] everything jelled." [8]

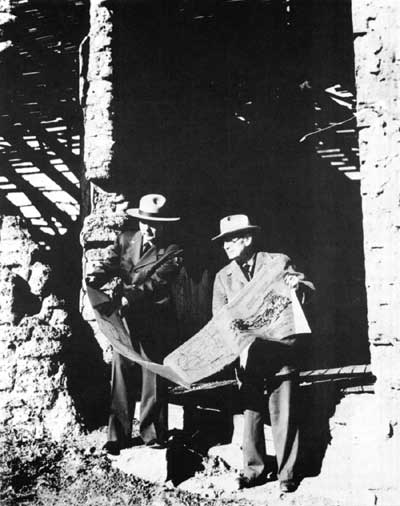

Figure 17. Superintendent Michael Becker

and Barry Scobee reviewing Master Plan (1963).

Courtesy Fort Davis

NHS.

One reason that "everything jelled" at Fort Davis was the unification of historical research by Bob Utley, both for the historic structures and the visitors center/museum complex. In the summer of 1962, Utley combed the files of the National Archives in Washington to prepare both documentary and photographic evidence of the existence of the old military post. Thomas J. Allen, Utley's boss at SWR, informed the chief architect of the park service's Western Office of Design and Construction (WODC) that Utley had run into delays because of the distinctive nature of Fort Davis research. "The guidelines for preparing historic structures reports were designed for the problem of a single building," said Allen in September 1962. Fort Davis compounded this situation because "we have more than fifty historic buildings or sites of buildings, about half of which are represented by standing structures or remnants of structures." Utley had also discovered that "the documentary material on Fort Davis located in the National Archives has significant gaps that complicate the task of preparing the historic structures report." For these reasons, Allen suggested that Utley travel to San Francisco to discuss the Fort Davis plan with Charley Pope the historical architect of WODC, and then to write his draft based upon the linkage of the concerns of the NPS' architectural and historical offices. [9]

Upon Utley's return to Santa Fe from consultations with San Francisco NPS officials, he realized that Fort Davis' lack of staff and management would hinder standard park service strategies for supervision of construction work (especially given the project's isolation from other NPS sites, and the high volume of work to be undertaken). In addition, Utley had not completed all his own historical research for the museum. James M. Carpenter, acting SWR director, told WODC officials in November 1962 that work needed to begin as soon as practicable on the overhanging porches to protect the facilities on officers' row, but that private contractors could not be left alone on site to complete the task, for fear that "it would not be given the consideration that the historic structures deserve." Sanford Hill, chief of WODC, added to the sense of urgency by noting that "our plan for the Southwest Region this year consists entirely of the work at Fort Davis." He wanted to transfer to Fort Davis on or about January 1, 1963, a staff architect to oversee plans for "immediate support and shoring of walls, roofs and grounds to preclude further deterioration." Such a person could then prepare additional historic structures reports for later phases of stabilization, "supervise any necessary Day Labor and Contract work," and draw blueprints for "reconstruction of the Barracks Building No. [20] which probably will be restored as a Visitor's Center and Administration Building." The fact that Fort Davis had $40,000 available for construction work appealed to Allen and Hill, and the two discussed how to move the project forward without having to send everything to the central office in Washington. [10]

The arrival of Utley's reports in regional and WODC offices allowed its supervisors to comment upon the unconventional strategies suggested for such a park as Fort Davis. A. Clark Stratton, assistant director for design and construction in Washington, praised Charley Pope's original concept of overhanging porch roofs. "The proposal to protect the buildings surrounding the parade ground by means of limited restoration consisting of new roof structures and porches which will return the buildings to their original image," Stratton told the SWR director, "is considered here to be a desirable and welcome departure from past practices." Robert Utley remembered Pope's design as "revolutionary and brilliant," especially in light of Region III's focus on archeology over history. Stratton also declared Utley's report an "excellent . . . framework for consideration of the treatment of Fort Davis as a whole." Stratton's only reservation was the call for rehabilitation of the post hospital, which he saw as "not as defensible as are the other proposed restorations." Roy Appleman, Washington office (WASO) staff historian, concurred in Stratton's judgments, calling the hospital "a major financial undertaking, together with its subsequent furnishing and maintenance." Appleman favored "retaining the hospital as a ruin, giving it treatment similar to other buildings of this character in the Fort area." The WASO historian then went beyond Stratton's comments to suggest that the visitors center (which he agreed should be housed in the barracks building) be modeled upon Homestead National Monument, in Beatrice, Nebraska. Homestead had "large wall historical murals which reflect the theme for the place." A staff historian could be dispatched to Homestead, said Appleman, to devise a similar depiction for the visitors center at Fort Davis. [11]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foda/adhi/adhi4.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2002