|

FORT DAVIS

Administrative History |

|

Chapter Two:

Closing a Fort, Preserving a Memory: Private Power and Public Initiative in Fort Davis, 1890-1941 (continued)

The Davis Mountain park plan of the 1920s did try to follow the pattern of "monumentalism," which by necessity ignored an historical resource like old Fort Davis. What is interesting about the local boosters' strategy is their awareness of the sentiments in Congress and the state legislature for park programs linked to economic development. The failure of Hudspeth' s park bill would not daunt the Fort Davis merchants, who instead regrouped in 1926 to press the Texas Highway Department to build the "Davis Mountains State Parks Highway." Known locally as the "Scenic Loop," the route would meander some 74 miles west of Fort Davis through the lands of ranchers, permitting them better access to the railroads and markets away from west Texas. The idea took shape in September 1926, when a group of merchants, bankers, and ranchers met in the back room of the Fort Davis State Bank, across the street from the county courthouse. Among the attendees was a summer visitor, State Senator Thomas Love of Dallas, who declared his willingness to sponsor a bill in the legislature to create the highway. This would also generate jobs in the construction trades in the Davis Mountains, as well as monies to purchase ranch lands from private owners. [38]

Part of the impetus in 1926 for the Scenic Loop also came from the outside, as in the words of Jacobsen and Nored, a "slightly eccentric prosperous North Texas banker," William Johnson McDonald, donated upon his death that year over $1 million to the University of Texas to build an astronomical observatory in his name. The university lacked the expertise to design and construct such a facility, and thus contacted the University of Chicago for advice. Its professors suggested the mountains of far West Texas for their clear air, open space, dry climate, and most importantly their lack of city lights to obscure night vision. A loop road out to the potential observatory site sixteen miles northwest of Fort Davis would enhance the attractiveness of the location to the University of Texas, and would also appeal to state legislators concerned about the economic viability of the route. [39]

Figure 5. Visitor at Sleeping Lion

Overlook. Note good condition of recently abandoned

structures.

Courtesy Fort Davis NHS.

As Senator Love's proposal wended its way through the Texas statehouse, local interests cast about for additional evidence of the value of the Scenic Loop. In 1927, the West Texas Historical Association called for preservation of old Fort Davis, but this did not appear in the legislation signed that year by Governor Dan L. Moody to build the highway. Then in 1929 Representative Hudspeth reintroduced in Congress his Davis Mountains national park bill, which again did not include the fort, and which also failed of passage. Resistance to these plans bothered the local interests, as they knew of efforts in Texas and nationwide to accelerate the process of park creation. Michael Kammen noted that in 1927, the state of Virginia, no doubt responding to the plans of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to restore Colonial Williamsburg, "undertook the first large-scale attempt to identify historic sites for motorists." This concept of expanding parks beyond natural beauty to human history found a receptive audience in Austin, and the state legislature followed Virginia's lead in erecting roadside historical markers. [40]

Three events in the late 1920s and early 1930s shifted the focus among local interests from the Davis Mountains to the preservation in town of old Fort Davis. First, the onset of the Depression slowed the pace of state highway construction, exacerbating a condition that the locals may not have realized: the opposition of the highway department to the whole idea of the Scenic Loop. Gene Hendryx, owner after World War II of the only radio station in the area (KVLF in Alpine), and also a state representative for the Davis Mountains in the 1960s, learned when he promoted expansion of the Davis Mountains state park that highway planners had not been consulted on the feasibility of the route, nor had local ranchers been satisfactorily compensated for their lands. In addition, said Jacobsen and Nored, "so many other more heavily traveled routes were begging for improvement." It seems that the local promoters of the road used their political clout in Austin to gain passage and the governor's signature. For that reason the route would take years to complete, with its dedication not held until 1947; 21 years after Barry Scobee wrote a news story about attending the meeting with Senator Love in the Fort Davis State Bank to commence the road project. [41]

Just as the Scenic Loop showed promise, a Hollywood western film star named Jack Hoxie came to Fort Davis with a plan to make the post nationally famous. William K. Everson described Hoxie in A Pictorical History of the Western Film (1969) as "a player of restricted talent and variable pictures," whose "huge popularity must be attributed to the fact that he made more good pictures than bad ones and that when they were good, they were very good." Historians of western film consider the 1920s as the "golden age" of the genre, in that this was the period of rapid expansion of the technology for feature films, and the growth of urban audiences who were neither discriminating in their tastes nor knowledgeable of the accuracy of the story lines. Hoxie, who began his career under the name "Hart" Hoxie (perhaps to link himself to the most prominent western silent film actor, William S. Hart), "was a big, amiable oaf, whose large frame made him seem clumsy afoot and whose expression suggested that his mind was a complete blank." His great gift, however, was his horsemanship, and Everson described Hoxie as "something else again, an expert rider and stunter." Most noted for the film, Don Quicks hot of the Rio Grande, Hoxie impressed audiences nationwide with his "elaborate stunts, leaps, transfers from galloping horse to moving train," while the picture itself benefitted from a series of "majestic exteriors." [42]

When not making movies in the 1920s, Hoxie found employment in Oklahoma on the Miller Brothers "101 Ranch," made famous as a touring Wild West show and working ranch because of its promotion of the era's premier cowboy star, Tom Mix. Hoxie followed in Mix's tradition of athletic ability and presence on a horse, and the owners of the 101 Ranch hoped to find a site for Hoxie to highlight his skills (and also downplay his limitations). This they believed would be in the Davis Mountains, and thus Hoxie was introduced in the spring of 1929 to W.A. Wilson, secretary of the Marfa chamber of commerce. Wilson took Hoxie on a tour of the area, and the Alpine Avalanche reported that the movie star had "'fallen hard' for this environment." Hoxie and his entourage then drafted plans for a $250,000 resort and movie set to be housed at the fort, including "a half mile race track, a polo field, golf course, baseball diamond, a big swimming pool and a rodeo arena." The entire square mile comprising the John James estate's lands would be surrounded by a 55-inch wire fence, and a spokesman told the Alpine paper: "In repairing the old adobe structures and corrals the old outlines will be strictly preserved." [43]

Figure 6. Jack Hoxie (on right) and friends

at Fort Davis (1930).

Courtesy Fort Davis NHS.

For the next two years, the Hoxie company entranced Fort Davis and environs as only Hollywood can do. In May 1930, J.E. Pierce, president of the New York-based "Pacific Far West Pictures Corporation," came to "Hoxie's Stockade," as the post had become known, to discuss "the possibilities of old Fort Davis as a tourist resort and a place to make 'western' pictures." Speaking for Hoxie was W.A. Wilson, who had convinced three Fort Davis men (Lee Glasscock, Frank Jones, and Herbert Bloys) to sign a 25-year lease with the James family to use the fort. The lessees agreed to give the James estate $300 upon signing, another $300 after one year, $800 within two years, and $1,200 per year for the remainder of the agreement. In addition to this payment of $2,600, Messrs. Glasscock, Jones and Bloys would pay taxes and assessment fees on the property. Soon thereafter the three men received from Frank L. Sproul a 20-year lease on farm land north of the fort along Limpia Creek for an additional $7,000. They then subleased a portion of these properties to Hoxie and Wilson. [44]

Unfortunately for the local investors, the Hoxie company never could develop the property as advertised. The only major event staged at the post was a rodeo in March 1930, witnessed by over 2,000 people on a windy, blustery Sunday. The highlight of the day was Hoxie performing tricks on his famous white horse, Scout, and with his "trained dog Bunk." Hoxie's "leading lady," Miss Dixie Starr, also pleased the crowd with her performance "in a little melodrama wherein the Bunk came to the rescue," and with her "work with the rifle." Visitors sought more news of completion of the project, and one Sunday in March 1930 some 450 automobiles drove through the old fort grounds. One interesting note from the construction work in rehabilitating the ruins came when carpenters found along Officers' Row stone arrowheads embedded in the roofs, leading Barry Scobee to report in the Alpine Avalanche: "Indians used to lie in the rocks above the old fort and shoot arrows down at the soldiers according to local history and evidently there is something to it." [45]

Whether or not there was "something" to the local lore about Indian attacks on the post, the Depression and Hoxie's fading appeal did harm to the town's dream of Hollywood glitter and fame. Jacobsen and Nored (the latter a relative of investor Herbert Bloys) wrote years later that "by spring of 1931, Hoxie' s financial backers were in serious trouble themselves from the drop in oil prices." The cowboy star, in the authors' words, "conned numerous Fort Davis citizens into investing $100 [each] in his enterprise," and none "received a penny of their money back." Jacobsen and Nored then recounted local folklore about Hoxie's shortcomings as an actor; features blissfully ignored when the company was in town. Film historians echoed their criticism, albeit more tactfully. "Hoxie could neither read nor write," said Everson, "and genially accepted some rather cruel inside jokes about those failings in several of his films." The advent of sound pictures by the early 1930s rendered Hoxie useless in Hollywood, as he could not "read, remember, or deliver a line." He thus "drifted out of the movies" as quickly as he had hit Fort Davis with his dream of Hollywood on the Limpia. [46]

With the town of Fort Davis sadder but wiser as a result of the Hoxie affair, civic officials faced the third factor of change in their efforts to promote the Davis Mountains. Where highways and movies had failed, they hoped to take advantage of a new direction in the state and federal government towards parks and history. The administration of Herbert Hoover (1929-1933), noted in history books for its disastrous management of the nation's economy during the Great Depression, nonetheless seemed favorable to expansion of the nation's system of parks and monuments. Hoover and his Interior secretary, Ray Lyman Wilbur, applied liberally the Antiquities Act of 1906, which permitted the executive branch to set aside "man—made wonders or scientific curiosities" for preservation. Vance Prather of Fort Thomas, Kentucky, had written in March 1930 to Horace M. Albright, director of the NPS, about the need for a national park in west Texas. Among his suggestions were the future Guadalupe Mountain National Park near Carlsbad Caverns, Palo Duro Canyon near Amarillo, and "the Davis Mountain area, a mile high, near Fort Davis, an enchanting vista." What made this area appealing, said Prather, was "its vast road system, its easy access by way of the Bankhead, Old Spanish Trail, Glacier-to-Gulf, and other roads." Albright agreed to include Prather' s list in the upcoming NPS studies of new parks, calling it "very interesting and valuable to us." [47]

The defeat of Hoover in the 1932 presidential election did not daunt the boosters of Fort Davis, in that the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt promised even more aggressive action on behalf of the park service. "Whereas Hoover's ventures into history were non-political and bland," said Michael Kammen, "FDR' s uses of the past were shrewd and self serving." The desperate times facing the American people led Roosevelt to experiment with all manner of "New Deal" social and economic programs; what Kammen called FDR's "distinctive capacity to connect innovation with tradition." The 1930s also witnessed a breakdown of resistance to public support of historical institutions. "Had there not been a Great Depression," said Kammen, "it might have taken considerably longer for government at any level to concern itself with American history, myths, and museums." Roosevelt knew that "American society increasingly needed and sought a meaningful sense of its heritage in crisis times," and "since Americans disagreed about numerous policy issues during the 1930s, history seemed a kind of neutral ground." [48]

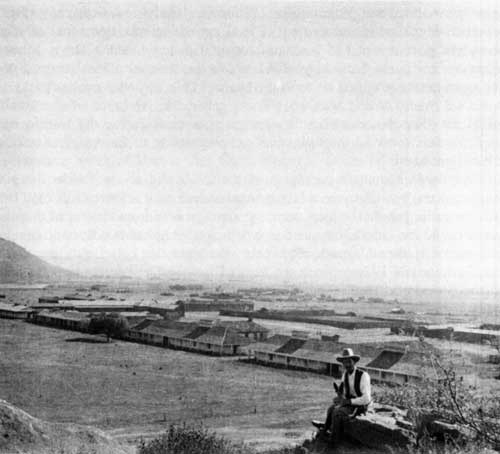

Figure 7. Abandoned Fort Davis looking

north from Sleeping Lion Mountain (early 1900s).

Courtesy Fort Davis

NHS.

The New Deal could come none too soon for boosters of Fort Davis or the Davis Mountains as national parks. On the last day of the Hoover administration (January 19, 1933), Horace Albright signed a recommendation drafted by Conrad Wirth of the Washington NPS office (abbreviated as WASO) to remove the Davis Mountains area from further consideration. Wirth wrote that the Texas state parks board had recently acquired 3,500 acres of land in the mountains along the route for the Scenic Loop. "The road is now being constructed," Wirth told Albright, "and the area is practically established as a State Park." A new presidential administration inspired local interests to resubmit their request, and the park service sent to the Davis Mountains the former superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park, Roger V. Toll, who had become an expert in surveying the potential of new park sites. Toll visited the Davis Mountains in the spring of 1934, and praised the area for its "rolling hills . . . excellent grazing grass . . . [and] numerous outcrops of granite." Unfortunately, the Davis Mountains did not compare to scenery such as Toll had managed in Colorado, and he concluded that the area had "pastoral beauty, but it is not spectacular." Toll suggested instead: "The area is more suitable for a state park than for a national reservation, and it is recommended that it be dropped from the list of proposed projects, but that cooperation with the State Parks Board be continued." [49]

That "cooperation" of which Wirth (a future NPS director) spoke came in the form of park service-supervised construction work at the Davis Mountains State Park, three miles northwest of Fort Davis on the road to the proposed site of the McDonald Observatory. Through a combination of state purchase and leasing of private lands, 2,130 acres of the Davis Mountains were targeted for a resort complex. Its salient feature was "the magnificent mountain setting," said a park service press release in August 1937, "which particularly is attractive to Texans, due to the fact that during July and August it is cool and green, while most of the state is hot and dry." The release said nothing about the ability of the mass of Texans in urban and rural areas to the east to gain access to a publicly funded resort, whose "most outstanding structure is the adobe Indian Lodge, which is an impressive Pueblo style, with sixteen guest rooms each with private baths." The lodge was "furnished throughout with Indian motif furniture made from native woods by the Civilian Conservation Corps [CCC]," and it came complete with "a spacious lobby with dance floor." The Scenic Loop and "several miles of foot and horse trails [made] the mountain scenery more accessible." [50]

While students of the post-New Deal era might note the irony of social welfare agencies like the CCC building such a luxurious facility, the NPS found itself besieged by local interests to hurry the construction and add more touches that would make the resort even more appealing. The CCC is better known to historians as one of the most popular of federal agencies created in the heady "First One Hundred Days" of the Roosevelt administration (March-June 1933). As its goal, the CCC sought the removal of young single males from the streets of America's urban centers, where idleness and lack of employment bred social problems and violence. Its 600 camps were located in rural and wilderness areas of the country, where they were managed by officers of the U.S. Army. CCC enrollees earned $30 per month, which included $10 to be placed in savings, $10 sent home to help with family expenses, $5 per month for room and board, and $5 for spending money. Youth learned discipline, work habits, and job skills in the camps, while the Army provided schooling in trades and mechanics. The NPS in turn offered planning and design capabilities for structures in nature; hence the park service's entry in the 1930s into the Davis Mountains.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foda/adhi/adhi2b.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2002