|

Fort Clatsop

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER THREE:

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

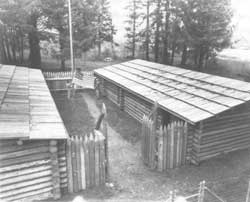

Fort Clatsop replica, August 1958, Burnby Bell is on the left.

(Photo by Deane W. Bond; courtesy of Oregon Historical Society, photo negative number

3869)

The movement to have the Fort Clatsop site nationally recognized goes back to at least 1905-1906 when the Oregon Development League of Astoria and the Oregon Historical Society sought legislation for a Congressional appropriation to purchase 160 acres at the site and erect a suitable monument in commemoration of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Senate Bill 440 was introduced in Congress in 1906 by Oregon's Senator Charles W. Fulton requesting an appropriation of up to $10,000. The bill was referred to committee and died there. [1]

The federal government did not consider the site again until 1935 when the National Park Service (NPS), in cooperation with the Oregon State Parks Board, conducted a survey of Oregon historical sites and their preservation needs. In this survey, it was determined that the best future for the Fort Clatsop site would be management by the Oregon state park system. Two years later, at the March 1937 meeting of the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historical Sites, Buildings and Monuments, the Advisory Board also recommended that the site be state-managed. These developments did not keep the local community from continuing efforts to obtain national recognition for the site. The Clatsop County Historical Society again unsuccessfully asked Congress to recognize the site as a national monument in 1948.

With the decision to build a fort replica in 1953 and the attention surrounding the site throughout the Sesquicentennial, the movement for national recognition was renewed. Site management had been difficult for OHS prior to the construction of the fort replica. The placement of picnic facilities and other improvements meant new management requirements at the site. OHS was not in a position to manage the undeveloped site, much less face these additional pressures. The local community and civic groups who had invested time, effort, and money into the replica project disagreed on how to best resolve the site's management. A large majority of the local community favored state management or the formation of a local group specifically to handle site management. Those individuals felt the federal government had shown little interest in the site, so why give them their replica? Clatsop County Historical Society member A.N. Thorndike, wrote with regard to federal control of the site, that no more than state level management should be attempted so there would be "fewer hands in our pockets or over our heads." [2] Editorials in the Oregonian and Astoria newspapers suggested that if the state of Oregon had created a state park at the site, it would not have been necessary to turn to the federal government for its protection. Senator Richard L. Neuberger, the Oregon Senator who would be responsible for drafting the enabling legislation for the memorial, wrote in 1956 that it was disturbing how much criticism he received from "people who make a fetish of opposing anything associated with the national government." [3]

Thomas Vaughan, director of the Oregon Historical Society, had a different perspective on the matter. For the site to have any future and reach its potential as a historic site, Vaughan believed it needed to be in the hands of the federal government. The limited finances of the historical society could not provide that future. Burnby Bell and Wesley Shaner, Jr., the key individuals in the replica project, agreed with him. In 1953, a Portland doctor named Franklin B. Queen wrote to Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay, formerly the governor of Oregon, and to Oregon's Congressman Walter Norblad asking that they pursue national recognition of the site. To that same end, Vaughan contacted Oregon's Senator Richard Neuberger.

Senator Neuberger was very interested in pursuing national recognition and drafted legislation for the consideration of the site as a national memorial. Senator Neuberger enlisted the help of fellow Oregon Senator Wayne Morse and Senator Henry Dworshak of Idaho, as well as Oregon's Congressman Walter Norblad. In July 1955, Senator Neuberger introduced legislation that required the Secretary of the Interior to investigate and report to Congress on the advisability of establishing Fort Clatsop as a national memorial. Prior legislation had asked for monument status. Monument sites generally have a specific natural resource or are historically significant by themselves. A memorial is meant to be commemorative of a certain historic event or individual. Senator Neuberger recognized that it was more appropriate for the site to be designated a memorial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition rather than a monument. Senator Neuberger's legislation passed the Senate with no objections.

When the bill reached the House floor, Congressman John Byrnes of Wisconsin questioned why taxpayers' money was being wasted on such legislation. He did not know who authored the legislation, but thought it ridiculous to pass legislation asking the Secretary of the Interior to do what he was already supposed to be doing under the Historic Sites Act of 1935. Congressman Clair Engle of California suggested that since the money and time had already been wasted in the Senate, they should just pass the bill on and suggested that maybe the author of the legislation wanted to "light a fire" under the Secretary of the Interior. Mr. Byrnes replied that it would be a costly fire. [4] After registering his complaint that the bill was a useless and unnecessary waste of the taxpayers money, the Congressman withdrew his objection and the legislation passed, becoming Public Law 590, 84th Congress, and signed June 18, 1956.

Prior to P.L. 590, the Park Service had responded to public requests for national recognition by referring to the 1937 decision by the Advisory Board. According to NPS Director Conrad L. Wirth, in his response to Dr. Queen, the Advisory Board had studied the site and "as a result of its studies of the history of the fort and its associations, the Board recommended that the Fort Clatsop area be preserved and developed as a state historical monument. It is our hope that the Clatsop County Historical Society, the Oregon Historical Society, and perhaps the State of Oregon will be able to carry out the recommendation of the Advisory Board." [5] Wirth continued to say that the Park Service was unable to help financially, but would provide technical assistance in site restoration as best it could. Director Wirth repeated the same response in February 1954 to Congressman Walter Norblad, who had inquired about the site on behalf of Dr. Queen. For Park Service administrators, the Fort Clatsop proposal for national recognition had been settled by the 1937 Advisory Board recommendation. The authenticity of the site was questionable due to the lack of actual physical remains and the alteration of the historic landscape due to agricultural and economic developments that had occurred over the years. The Advisory Board had determined Fort Clatsop not to be of national significance and therefore not worthy of inclusion in the National Park System.

With passage of Senator Neuberger's bill, the Park Service was forced to reconsider the proposal. The National Park Service, Region Four, assigned regional historian John A. Hussey as well as regional archeologist Paul J.F. Schumacher to fulfill the requirements of Senator Neuberger's bill. Hussey researched the site and its history, and in December 1956 and April 1957 Schumacher conducted archeological excavations. Schumacher reported finding evidence of European-American settlement, which had certainly occurred and was well documented, but found no conclusive evidence of the actual fort remains. [6]

On April 10, 1957, Hussey's "Suggested Historical Area Report" was completed. Hussey concluded that the site under consideration did contain the original site of the Corps of Discovery's winter quarters known as Fort Clatsop. He based his decision on the oral testimony and written correspondence regarding the location of the site, an examination of the Lewis and Clark Expedition journals for information regarding the location, and finally by comparing the journal descriptions to existing topography. Hussey determined that while the site did not match all journal information given, no other place along the river banks came close to being an alternate location. This combined with the record of nineteenth century visitation led Hussey to conclude that the actual fort had been at or near the present replica.

Hussey recommended first that the National Park Service and the Advisory Board recognize the need for a special area in the National Park Service for the commemoration of the Corps of Discovery. Secondly, he stated that the Fort Clatsop site met all of the qualifications to be a national memorial. Hussey went on to recommend that a survey be conducted of all the possible Lewis and Clark historic sites and that the most appropriate Lewis and Clark site be selected for the commemorative site. If the Fort Clatsop site was determined to be the most appropriate site, then Hussey suggested certain minimum boundary acquisitions for the memorial's establishment and that all mineral rights be obtained with any land acquisitions. If the Fort Clatsop site was not found to be the most qualified, then consideration was to be given to establishing the site as a national historic site in non-federal ownership.

The Advisory Board approved Hussey's report by a mail vote and recommended it be submitted to Congress along with the recommendation that the site be established as a national memorial as long as mineral rights could be secured. The Office of the Secretary of the Interior submitted Hussey's report to Congress along with its approval of establishing memorial status. On January 23, 1958, Senators Neuberger introduced Senate Bill 3087, cosponsored by Senators Wayne Morse and Henry Dworshak, in response to Hussey's report and the recommendations of the Advisory Board and the Secretary of the Interior. This legislation called for the memorial's creation and Congressman Norblad introduced similar legislation in the House. Senator Neuberger entered into the Congressional Record a letter regarding the importance of the Fort Clatsop site written by Dr. Burt Brown Barker, president of OHS during the Sesquicentennial construction. No objections were raised regarding the Fort Clatsop bill, which passed and was signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on May 29, 1958.

Prior to Hussey's report, the park service had continued to suggest state control of the site. John Hussey remembers negative attitudes toward the site by many in the Region Four office. [7] Lack of archeological evidence combined with a fort replica was considered by many as not the most appropriate historic site the park service could acquire. Many who lived near other Lewis and Clark sites in Washington State felt that Fort Clatsop should not be given national recognition without any consideration for their Lewis and Clark sites.

Photo of Fort Clatsop sign and county road, 1958. (FOCL photo collection) |

Photo of replica and site conditions, 1958, as seen from parking lot. (FOCL photo collection) |

Frank Turner, editor of the Longview Daily News in Longview, Washington, wrote that while Fort Clatsop was worthy of national recognition, it would be a travesty to give it without recognition of the site at Fort Columbia where the expedition actually completed their mission by reaching the Pacific Ocean. In February 1958, Turner requested Senator Warren G. Magnuson and Acting Secretary of the Interior Hatfield Chilson seek consideration of the Washington State Lewis and Clark sites. The economic benefits of a national memorial did not escape Turner and the influence of Senator Neuberger's involvement did not escape him either.

There were many factors contributing favorably to national recognition for Fort Clatsop. One was the relationship between the Oregon Historical Society and Senator Neuberger and their dedication to completing the necessary legislation. Senator Neuberger served on the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, which controlled legislation regarding the creation of new units under the National Park Service. Neuberger also had a personal interest in the history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and wrote a children's book on the subject. Another favorable factor was Douglas McKay's position as Secretary of the Interior during the 1956 legislation requiring a site evaluation. Douglas McKay, as noted earlier, was formerly the governor of Oregon and had been a principal speaker at the Fort Clatsop replica dedication in August 1955.

Hussey's recommendations changed the official Park Service position regarding the status of Fort Clatsop. The report determined the need for a Lewis and Clark commemorative site in the NPS system and that the NPS would be favorable to Fort Clatsop being designated as a commemorative site, if it was the best representative of all Lewis and Clark sites. Why the Advisory Board and the Secretary of the Interior chose to forego a survey and make Fort Clatsop a memorial is unclear. It is possible that a survey would have taken considerable time and money and cause political maneuvering among the Lewis and Clark states for a national memorial. The creation of Fort Clatsop National Memorial was a success primarily due to the commitment of the Oregon and Clatsop County historical societies, with the support of other civic groups and individuals from the area and the State. The memorial would not have been possible without the commitment of Senator Neuberger, as well as Senator Morse and Congressman Norblad, to succeed for their constituents.

The legislation for Fort Clatsop National Memorial remained unchanged until 1978, when amendatory legislation was passed by Congress adding the Salt Works site, which was then known as the Salt Cairn, in Seaside, Oregon, to the memorial holdings. The person primarily responsible for the amendatory legislation was Dr. Eldon G. Chuinard. Chuinard was a doctor and an avid Lewis and Clark historian, author of the book Only One Man Died, a history of the medical aspects of the Expedition. He was also the chairman of the Oregon Governor's Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation Committee. [8] Chuinard believed completely that the Salt Cairn needed to be attached to the Fort Clatsop site, the two being critically linked in the Expedition's stay. The Oregon Historical Society still owned the site and it was maintained by the Seaside Lion's Club.

In 1968, Thomas Vaughan wrote to Fort Clatsop Superintendent Jim Thomson suggesting the extension of the memorial to include the Salt Cairn. Superintendent Thomson wrote back to Vaughan stating, in his opinion, that the "negative aspects outweigh the positive." [9] The park would need an increased budget, the site was detached from the rest of the memorial which created travel and maintenance problems, and its authenticity was questionable. He did not mention the fact that the memorial could not include the one city lot that contained the Salt Cairn replica under the memorial's enabling legislation acreage ceiling.

John Hussey also responded to Thomas Vaughan's idea on September 19, 1968. He advised Vaughan of the proper channels for him to offer a donation to the Park Service, informed him that the National Survey of Historic Sites had determined the site was not of national significance, and let Vaughan know that the Survey Board's decision would be significant to the Park Service when considering his proposal. [10] The proposal lost momentum for awhile after this series of correspondence.

Dr. Chuinard began his campaign to have the site included in Fort Clatsop National Memorial in January 1973 when he contacted Fort Clatsop Superintendent Paul Haertel. Superintendent Haertel responded by rejecting the idea and submitted the same factors outlined by Superintendent Thomson in 1968. Chuinard wrote to Assistant Secretary of the Interior John Kyl on August 27, 1973, and asked for assistance in determining the proper procedure for OHS to donate the Salt Cairn site to the Park Service for inclusion in the memorial. Prior to Chuinard's letter, the new Fort Clatsop superintendent, John Miele, examined the site and reported to the regional office on the proposal. Miele reported that there was considerable doubt regarding the actual site and that recognition on the National Register would be suitable recognition for the site. [11] He also suggested that interpretation of the salt making could possibly be done on the current memorial grounds. With that information, Kyl responded to Chuinard declining the donation and stating that interpretation of the salt making process would be done at the memorial. This prompted an emotional response from Chuinard that would set the stage for the next five years of bargaining for the Salt Cairn addition. On December 6, 1973, a memo from Superintendent Miele to the regional office documented a phone call from Chuinard who expressed his displeasure at Assistant Secretary Kyl's letter. Chuinard indicated he would settle for nothing less than the addition of the Salt Cairn to the memorial. Superintendent Miele respectfully restated the Park Service's position regarding the proposed addition. Chuinard then called on Senator Mark Hatfield, Congressman Wendall Wyatt, and Oregon Governor Tom McCall, enlisting their support for his proposal.

On June 20, 1974, Senator Hatfield and Senator Bob Packwood introduced Senate Bill 3683 for the addition of the Salt Cairn to Fort Clatsop National Memorial, with Congressman Wyatt introducing similar legislation in the House. The bill was referred to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, where the legislation failed. Also in 1974, the nomination of the Salt Cairn to the National Register was rejected due to the sites questionable location and to residential development surrounding the replica site which compromised its historical integrity.

The Oregon Senators reintroduced their bill in the 94th Congress as Senate Bill 828. On November 7, 1975, the Office of the Secretary of the Interior recommended that Senate bill 828 not be passed. Prior to the 94th Congressional session, Congressman Wyatt's seat was won by Les AuCoin who helped take up the battle in the House. In 1975, Dr. Chuinard and the Oregon Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation Committee, in cooperation with the Oregon Historical Society, wrote a proposal on the Salt Cairn addition and sent it to Congressman AuCoin. This proposal was supported by the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office and the Parks and Recreation Branch of the Oregon Department of Transportation. While the second attempt at legislation was working its way through the Senate, the second nomination for listing on the National Register was again declined in 1976. By the end of the 94th Congress, the Senate had passed the Salt Cairn legislation.

Congressman AuCoin was not successful in the House. The House Interior Subcommittee did not want to consider an addition to which the NPS objected. The Park Service never altered its opposition to the addition and the failure of two nominations to the National Register defended their position. In a letter to Dr. Chuinard dated March 23, 1978, Congressman AuCoin explained that the "park service's primary opposition is based on the incompatibility of the Salt Cairn memorial and the surrounding residential area with further development which it feels will be absolutely mandatory if the memorial is to justify federal involvement. Particularly spooking the NPS is the notion of acquiring residential land and residences near the Salt Cairn, or worse, being forced to acquire them." [12] AuCoin recommended a show of support from Seaside, most importantly from neighboring residents, to assist the house bill.

Dr. Chuinard, the Lewis and Clark committee, and Thomas Vaughan became exceedingly irritated at the National Park Service throughout this process. The frustration prompted Vaughan to write in May 1978 that soon the Park Service would be questioning the validity of Crater Lake. [13] With the letter from Congressman AuCoin, Chuinard rallied support from Seaside, as well as support from Oregon Governor Robert Straub, who wrote to Secretary of the Interior Cecil Andrus in April 1978. However, Governor Straub wavered in his support when he learned that the acquisition of residential properties might be necessary for interpretation of the site to NPS standards.

Dignitaries at Salt Works dedication. Shown are Thomas Vaughan,

a Seaside Lions representative, Superintendent Bob Scott, NPS representative,

Frenchy Chuinard.

By May 1978, the back and forth struggle between Chuinard and the Park Service over the Salt Cairn was at a head. The Park Service maintained that the site's location was questionable and that the historic scene was non-existent and could not be recreated without the acquisition of at least the piece of property separating the site from the beach and ocean. Chuinard responded that although the exact site could not be accurately determined by archeological research, they should not discount oral testimony from the turn of the century. He also stated that they were not asking for immediate development of the Salt Cairn site, only that the Park Service accept management of the site so it had a secure future. For every concern the Park Service expressed, Chuinard had a response.

The turning point came with the appointment of Congressman Phillip Burton of California as the chairman of the House Interior Subcommittee during the 95th Congress. Burton developed the tactic of the omnibus bill during a time when Congress became increasingly in control of the creation of new park units. [14] Burton pulled together many individual proposals for park units into one larger bill that would ensure enough votes for it to pass. With his position as chairman in 1978, Burton compiled what would be called the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978. This act included the Salt Cairn addition to Fort Clatsop National Memorial, created a dozen parks and increased the acreage of a number of others. To ensure the votes of the Oregon delegation, the struggling Salt Cairn legislation was included and the bill passed and signed into law on November 10, 1978, by President Jimmy Carter. The Oregon Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation Committee and the Oregon Historical Society gladly planned a transfer ceremony which was held on June 23, 1979, with Senator Hatfield in attendance. The tenacity of Dr. Chuinard and his fellow supporters paid off and the Park Service adjusted to the addition of the Salt Cairn to Fort Clatsop National Memorial.

The enabling and amendatory legislation for Fort Clatsop National Memorial is typical of the legislative process for historic and commemorative sites. The 1935 Historic Sites Act delegated control and regulation of the nation's historic sites to the National Park Service, but its authority and legitimacy in controlling the selection of these sites has been challenged by the public and by Congress. In his book, Remaking America, John Bodnar states that regardless of "how hard the service attempted to keep the process orderly, political influence, local pride, and personal feeling constantly intruded into the deliberations of the NPS professionals." [15] From 1935 through the 1980s, a broad mix of historic sites were given national recognition with little regard for Park Service guidelines. For congressional members, historic sites provide an opportunity to give something to their constituents, as well as serve their own personal pride in the history of their district. Historical parks generally require small budgets, usually relieve a local historical society, and generally don't require land condemnation. [16] In the campaign for national recognition, the Fort Clatsop site had strong community support dating back to at least 1905, the support of the state historical society, and, most importantly, the support of Senator Richard Neuberger and the Oregon congressional delegation. These factors resulted in the successful establishment of Fort Clatsop National Memorial.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

focl/adhi/adhi3.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jan-2004