.gif)

MENU

![]() Life History

Life History

|

Fauna of the National Parks — No. 6

The Bighorn of Death Valley |

|

LIFE HISTORY OF THE DEATH VALLEY BIGHORN

Water

Water requirements of the bighorn in Death Valley can be separated from food requirements only with difficulty since they are so interrelated. It has already been pointed out that under certain conditions the quantity and quality of available food supplies may control the need for free water. Perhaps the word "need" should be defined to clearly include "wanting" or "preferring" as well as "necessary." All of the existing data apply only to what the bighorn prefers in water needs. We know nothing as yet about how much free water it must have to survive. The hypothesis that it can survive with no free water at all will not be discussed here because we have found no evidence to support it.

What is indicated here is a constant need for water, varying in intensity with changes in weather, forage, and activity.

Requirements by Season

In simplest terms, the demand for water increases as the supply decreases. Summer conditions, with longer days and related increases in insolation, aridity, and rate of surface evaporation, are aggravated by the explosive activity and heightened metabolism of the rut. The hottest, driest days (tables 3, 4, and 5), unless relieved by summer rain, coincide with the height of the running and fighting stage of the mating season in late July through August and into September.

This report includes four tables pertinent to water requirements. Table 2, the Nevares Spring sheep record, shows the dates, temperatures, and age class and sex tabulations, the arrival and departure times, and the number of hours observed. Variability is again immediately noted, with high temperatures being the most stable item recorded. The number of animals watering in 1 day ranged from 1 to 12, with no apparent correlation between the hottest days and the number of sheep coming in to water. The first 3 weeks of observation disclosed a preponderance of ewes and lambs on the scene, and the last 10 days show more and more rams. There appears to be no correlation between age class and sex and the time spent by the animals within our range of observation.

TABLE 3.—Official air temperature record, Death Valley National Monument headquarters for July, August, September, and October 1957

| July | Temperature (° F.) | August | Temperature (° F.) | September | Temperature (° F.) | October | Temperature (° F.) | ||||

| Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | ||||

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Average |

116 116 118 120 122 119 115 120 119 116 116 115 114 118 120 118 114 113 113 112 110 110 115 117 117 114 118 119 121 121 117 |

89 92 85 86 88 92 85 89 97 89 93 90 85 85 91 89 90 88 87 87 81 81 79 82 81 87 90 91 91 93 88 |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Average |

121 119 118 117 115 109 107 111 116 116 116 115 117 117 115 120 122 121 116 110 108 111 115 117 112 114 112 108 107 101 101 114 |

86 92 93 92 88 84 80 81 81 88 90 85 87 93 90 79 69 84 75 77 71 72 84 |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Average |

106 109 111 112 111 117 117 118 117 114 111 109 108 106 105 101 101 95 99 98 102 104 106 107 108 107 105 108 106 105 107 |

72 75 79 82 80 81 83 87 87 90 84 83 79 78 77 78 73 70 74 79 79 73 75 77 81 81 74 80 82 79 |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Average |

102 94 93 90 88 88 88 89 95 95 94 83 83 85 82 90 92 92 91 89 71 76 81 86 89 81 85 90 87 83 78 87 |

76 71 73 64 63 62 63 60 62 65 62 60 68 68 67 63 64 64 65 69 58 51 56 59 62 65 58 63 62 60 65 64 |

TABLE 4.—National Park service ground temperature readings in Furnace Creek vicinity, May—November 1957

| Date | Ground temperature (° F.) | Air temperature (° F.) | ||

| Station No. 1 | Station No. 2 | Station No. 3 | ||

| May 3 May 21 June 3 June 16 July 1 July 14 July 30 Aug. 11 Aug. 28 Sept. 10 Sept. 22 Oct. 9 Oct. 21 Nov. 14 |

132 139 156 158 164 160 157 157 150 144 136 130 115 110 |

146 152 168 174 180 178 179 180 178 178 168 165 152 144 |

138 150 165 164 174 173 166 168 164 158 148 148 134 126 |

102 105 117 121 123 122 120 |

TABLE 5.—National Park Service ground temperature readings at Badwater and Tule Spring, May, June, July, and August 1958

| Date | Ground temperature (° F.) |

Date | Ground temperature (° F.) | ||

| Badwater (south) |

Badwater (north) |

Tule Spring (north) |

Tule Spring (south) | ||

|

May 5 May 31 June 13 June 28 July 12 July 26 Aug. 14 Aug. 30 Sept. 27 |

150 160 154 160 168 164 152 154 160 |

142 140 154 160 170 170 162 152 156 |

May 4 May 25 June 13 June 27 July 12 July 26 Aug. 14 Aug. 30 Sept. 27 |

144 154 154 156 190 184 160 162 158 |

148 142 152 154 178 176 162 162 158 |

Amounts Taken

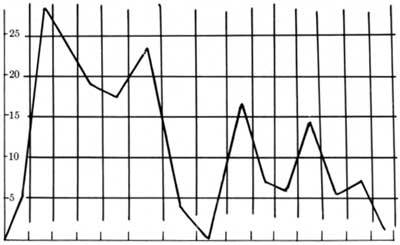

The question of time preference for watering, as shown in table 6, indicates a definite leaning toward the morning hours, a curious abstinence during the noon hour, a 50 percent resumption of activity shortly after noon, and an irregular decline to sundown. It is worth noting that the highest incidence came before sunrise and the lowest after sunset, with only one animal coming in so late during the entire 30 days.

The ground around the spring areas usually was swept at dusk to eradicate the sign and was examined at dawn for sign of nocturnal watering. There was no evidence of nighttime use, but on several occasions animals were found standing at the springs or heading away from water at first visibility.

Actual drinking time of individual animals is partially recorded in table 7. While this record is far from complete, it offers a fair cross section of all age classes and sexes and is sufficiently repetitious in incidence to justify analysis. There are more records of rams than ewes and lambs for two reasons. In the first place, there were more rams to be recorded; and in the second, very often when the ewes and lambs came to springs surrounded by tall grass we were unable to determine actual drinking time. The rams seldom used these areas and when they did their greater size made it possible to determine by body movement whether they were eating or drinking.

TABLE 6.—Hourly record of bighorn drinking at Nevares Spring, from Aug. 11 to Sept. 10, 1957

| Sex and age of animals | Number of animals drinking during morning hours from— | Number of animals drinking during afternoon hours from— | |||||||||||||

| 5-6 | 6-7 | 7-8 | 8-9 | 9-10 | 10-11 | 11-12 | 12-1 | 1-2 | 2-3 | 1-4 | 4-5 | 5-6 | 6-7 | 7-8 | |

| Ewes and lambs Rams Total |

2 3 5 |

11 18 29 |

14 9 23 |

10 9 19 |

7 11 18 |

10 12 22 |

2 2 4 |

0 0 0 |

5 11 16 |

3 4 7 |

4 2 6 |

8 6 14 |

4 1 5 |

3 3 6 |

0 1 1 |

TABLE 7—Drinking time of bighorn at Nevares Spring, 1957

[E, ewe; L, lamb; R, ram]

| Date | Number of animals by age class and sex |

Drinking behavior | Drinking time (minutes) |

|

August: 15 16 16 16 17 18 18 19 20 20 21 22 23 23 24 25 25 26 27 27 27 27 27 27 28 28 29 30 31 September: 1 2 3 4 4 4 4 5 6 7 7 7 8 9 9 9 9 9 10 |

2 (1 E, 1 L) 2 (1 E, 1 L) 1 (1 R) 2 (1 E, 1 L) (above) 2 (1 E, 1 R) 4 (1 E, 1 L, 2 R) 6 (2 E, 2 L, 2 R) 1 (1 R) 3 (1 E, 1 L, 1 R) 2 (1 E, 1 L) 1 (1 E) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 3 (1 E, 1 L, 1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 E) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 2 (1 E, 1 L) 1 (1 R) 2 (1 E, 1 L) 1 (1 E) 2 (1 E, 1 L) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 2 (1 E, 1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 L) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 R) 1 (1 E) 2 (1 E, 1 L) 1 (1 R) |

Drank intermittently for 45, 50, 30, 29, 20, and 10 seconds. 2d drinking After chase 2d drinking 2d drinking Drank for 3- and 2-minute periods, intermittently. |

5 11 2-1/2 1 10 3 5 3 3 7 8 2 2 6 3 8 3 1 4-1/2 10-1/2 3 19 7 4 6 8 5 2-1/2 6 1-1/2 5 7 6 10 5 4 2-1/2 3 3 7 4 2 2-1/2 6 4 3 6 12 |

Note.—Average drinking time: Ewe—6.8 minutes; lamb—3 minutes; ram—4.2 minutes; ewe and lamb (together)—6 minutes; ewe, lamb, and ram (together 6.1 minutes; for all animals—5.3 minutes.

Aside from these records of time spent in drinking, we have nothing but estimates of amounts drunk by individuals. On August 19, 1955, a ewe at Virgin Spring drank close to 3 gallons of water, and her 7-month-old but still nursing lamb drank about half a gallon. On January 16, 1956, after 3 weeks without water, the Furnace Creek Wash band of eight traveled 4 miles to Navel Spring, drank all of the then available 7 or 8 gallons of water, and with at least two of the number still thirsty went a mile back on Paleomesa for the night. We "bedded" them there, camping for the night in freezing weather to find them on their feet at their bedding site at dawn. None came back to drink. On March 24, 1956, a band of four ewes, two lambs, and one ram made the same trip, found 12 gallons of water and left 2, for a probable average of over a gallon and a half for the adults and less for the lambs.

Finally, in table 8, we have approached the question of how long they voluntarily go without drinking. In this table no attempt is made to define the limits of time involved. It is offered as an indicator only, since it records the relative time lapses for only one area with one segment of the entire population for 1 month of one summer, and it discloses a variation so wide as to suggest that in this phase of the life history of the bighorn repetition of observations may be multiplied by generations without definition.

TABLE 8.—Bighorn watering record at Nevares Spring, Aug. 11 to Sept. 10, 1957

| Animal watering | Date and temperature (° F.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| August | September | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 116° | 12 115° | 13 117° |

14 117° | 15 115° | 16 120° |

17 122° | 18 121° | 19 116° |

20 110° | 21 108° | 22 111° |

23 115° | 24 117° | 25 112° |

26 114° | 27 112° | 28 118° |

29 117° | 30 101° | 31 104° |

1 106° | 2 109° | 3 111° |

4 112° | 5 111° | 6 117° |

7 117° | 8 118° | 9 117° |

10 113° | |

| Ewe and lamb | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ram | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Long Brownie | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 rams | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 ewes | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 lambs | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Lady | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fuzzy | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tabby | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Little Ewe | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marco | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dark Eyes | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light Neck | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Longhorn | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brahama | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Little Brahma | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mahogany | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Slim | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Knocker | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Horns | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A ewe | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Widow | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 lambs | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| White Socks | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rambunction | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lefty | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Low Brow | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrow Collar | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Little Brownie | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baby Brownie | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Roughneck | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Hook | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Full Curl | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nevares | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deer | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scrubby | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Humpy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rambunctious II | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Little Joe | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tan Rump | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flat Horn | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Skinny | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tight Curl | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Toby | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Low Curl | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nevares II | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stocky | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Broken Nose | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Curly | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No. 27 | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, some points in Table 8 immediately become apparent. The number of times each animal appeared during the 30 days ranged from once only for several to 10 visits for The Hook, who made his first appearance on the 10th day of observations and thereafter set the summer's record for frequency of drinking. It seems safe to conclude that he had been watering at some other spring and decided for some reason to stay on here.

With the exception of three, the one-time visitors were all rams making the rut-run from one spring to another. Three lone rams drank on at least 4 consecutive days. This may indicate a greater need for water on the part of rams but it may not, because the ewe has but one reason to come to the spring and that is for water. She shows up only when prompted by thirst. The ram, on the other hand, may be drinking every day solely because of proximity to water, while on his primary business of racial propagation. This in itself creates a greater expenditure of energy in him than it does the ewe since she is concerned only with her own oestrous cycle, whereas his interest and activity quickens with the sight, sound, and scent of every ewe in the herd. The evidence points toward a greater use of water by rams during the rut. We recorded three instances of rams coming in twice in 1 day but none for ewes.

Table 8 indicates that under these conditions resident ewes and lambs come to water every 3 to 5 days on an average. This means going from 1 to 3 full days without water. The almost double length of time for some animals suggests alternate appearances at two springs, possibly combining Scraper Spring, 5 airline miles to the north, with Nevares to make one home area. How much time rams take or how far they travel on their jaunts from spring to spring is not known. Two of the rams were both known from Navel Spring area 12 airline miles to the south, and both appeared to be heading north toward Scraper Spring when they left Nevares.

The irregularity of five of the ewes seems to indicate multiple use of springs by some ewes as well as rams. A typical instance to support this conclusion occurred at Nevares Spring at 9:30 a.m. on September 5, 1958. It was already 105° in the shade when three bighorn came in from the south on the "Needle's Eye Trail." They were a ewe, a 9-month-old lamb, and a yearling ram. They were the poorest sheep we had ever seen there, walking slowly as though exhausted, heads down, and every rib was showing. The ewe was a true Nevares type, with high shoulders, rangy build, and long, high horns. Was it Longhorn or Long Brownie? As she came closer we knew it was neither. The right horn was broken off—nearly half gone. This could have happened to Longhorn or Long Brownie, but the remaining horn, as long as theirs was, had a hook toward the tip which was unique with this ewe. This one was older, too, at least 10 years old, with conspicuous gray patches at the base of the horns very much like White Horns of Furnace Creek Wash. Long horns are characteristic of the Nevares type sheep, but the horns of this one were long even for them.

Although we hadn't seen this ewe before, this was not her first time in. She went slowly but directly to Old Spring and began to drink, and the young ram and the lamb joined her, whereupon she trotted 10 yards down to Trail Pool and drank again. The youngsters followed her there and they drank for 5 full minutes. The ewe and yearling then moved a few feet away and stood still, absorbing their water, but the lamb continued to drink for another 2 minutes. Then all three of them stood, filling out like a dried prune fills out when it comes in contact with moisture. This striking bodily transformation following recovery from dehydration is discussed under "Watering Behavior."

For half an hour, these three bighorn ate grass (Sporobolus airoides), and then the ewe and yearling started up the mountain, but the lamb went back to Old Spring and drank for another 3 minutes, ate grass, and expanded while the ewe and yearling waited a hundred yards up the mountain. None was poor looking then. They looked too full and fat to move, and although it was only 108° in the shade they panted, open mouthed, as they moved into the shade and went into siesta at 11 a.m.

How long it had been since they had drunk or how far they had traveled to get to water will never be known, but their fatigue was great. They rested until 4 p.m.—5 hours—then came down into the wash and browsed on Bebbia for half an hour. After that they returned to the spring area and grazed for 2 full hours on alkali sacaton, bluestem, black sedge heads, Mohave thistle, and mesquite. At 6:30, after feeding within a few feet of water, they left without drinking again and stopped to browse the first desertholly they came to. They were still browsing on holly when darkness fell.

At 3:15 the next afternoon this ewe and her lamb and the yearling ram came back and again drank at Old Spring. This was the first record we had of a band coming in on consecutive days. Rams have often done it, but not mixed groups. Again, the fatigue of the day before was emphasized and the importance of food supply at spring areas became increasingly clear, for they fed today as voraciously as yesterday.

After a half hour of energetic grazing they drank again, the ewe and ram for 1-1/2 minutes and the lamb for 2-3/4 minutes. The lamb, as yesterday, eating and drinking for a longer time than the others.

At 4:05, the lamb again leading, they went across the wash and into the shade of the Cut Bank. They rested there until 5:30, when they began browsing northward on Bebbia and Encelia and disappeared in the South Wash as the sun went down.

Where they had come from, or why, we never knew, but we saw them often after that and they grew fat and sleek as the summer ended. Their move from one home to another was successful.

Our evidence to date indicates that if bighorn are near enough to water in hot weather they will probably drink every day, but 1 full day to 3 full days without watering is at least common preference. We have no evidence to support the idea that they might survive with no free water at all, even in the winter or at higher elevations. On December 20, 1954, we followed a band of ewes and lambs to water in a tinaja (or "tank"—a cavity in the rock, often full of sand or gravel, holding water for a time after runoff) at sea level near Badwater. They came again to the same tinaja the next day and found it dry. The following day they climbed several miles up into the Black Mountains to Pothole Canyon, a mile north of Badwater; and while we did not see them drink there, later investigation disclosed their contact with water.

On January 16, 1956, we followed the first Furnace Creek Wash band of eight bighorn 4 miles to water at Navel Spring. They traveled from an elevation of 3,000 feet to an elevation of 1,800 feet in 40° weather. Another band of seven made the same trip in March.

On February 2, 1957, at an elevation of about 5,000 feet a band of 10 rams traveled 2 miles through snow to break the ice and get a drink immediately after a storm, in freezing weather.

In addition to these isolated and special instances, the dry period from July 1955 to January 1957 found dozens of bighorn watering regularly throughout the entire 18 dry months. The interval between visits to water during the winter was much longer than in summer, ranging from 10 to 14 days instead of from 1 to 3.

Young lambs show some evidence of requiring water oftener than adults, as in the case of the ewe, lamb, and yearling ram previously described. Old rams past their prime are often found farther away from known water sources than bighorn of any other age class or sex.

Shortages

"Water shortage" in Death Valley is a term requiring some definition, since it is related less closely to amount of water, but very importantly to the time and distance from an available supply.

One of the problems inherent to the area in general is our lack of knowledge of available water sources. During this study we have found many sources of "permanent" water, once known and utilized by man but unmapped, forgotten, and no longer known to the present inhabitants of the region.

"Forgotten Creek," which we located February 11, 1955, is a series of springs, some of potable water and some not, culminating in a creek nearly a mile long. It is the center of old game trails converging down out of the Grapevine Mountains; but it is, mysteriously, unused at the present time. The remnants of a barbed wire barrier across the mouth of the canyon and a rusty tin star from a plug of chewing tobacco are the only signs that other men once knew of its existence.

Corkscrew Spring on Corkscrew Peak, elevation 4,000 feet, when first investigated by us on December 8, 1956, turned out to be an ancestral bighorn stronghold of the first order. Fire Spring, a thousand feet below it, discovered earlier in the autumn by Lowell Sumner, was as mysteriously unused as Forgotten Creek, until in December 1960 we discovered that, like Willow Creek, it had inexplicably been put back to use by bighorn.

One of the most significant rediscoveries of a water supply was that of Twin Springs, June 11, 1957, at an elevation of about 4,000 feet, 5 miles southwest from Stove Pipe Wells on Tucki Mountain. Tucki is said to be an Indian word for sheep, and yet as far as we had known there was no free water in the Panamints north of Blackwater Spring, which meant none at all on Tucki. Geologist Charles B. Hunt reported a salty spring at Shoveltown at the base of Tucki Mountain, with old game trails and old sheep sign, indicating past use of the area. In April 1958 the West Coast Nature School brought us fresh bighorn sign from upper Mosaic Canyon on the north side of Tucki. There had been no recent rains in the area to produce pothole water. This indicated either that there was a permanent source we knew nothing about or that they were drinking from the Shoveltown salt spring. An unlikely alternative was that they were ranging 20 airline miles north from Blackwater Spring.

The most plausible of these alternatives was the existence of an unknown water supply. We began to hunt and inquire. Park Ranger Matt Ryan at Emigrant Station became interested, and his inquiries finally produced results. Through an oldtimer in Beatty, Nev., he heard of "a big spring on the mountain above Stove Pipe Wells Hotel." Ryan asked Mrs. Peg Putnam of Stove Pipe if she had ever heard of it. She had, and showed him a tiny green spot high up in the upper drainage of Mosaic Canyon.

On June 11, 1957, Matt Ryan and I climbed for 6 hours through remarkably steep, rough, and barren terrain to a point about a mile below Tucki's 6,700-foot crest. There we found, amid chin-high columbines blooming in a knee-deep green island 100 yards long, another ancestral stronghold of the bighorn, 16 airline miles from its closest neighbor and supporting a population leaving as much sign as we had found anywhere with the possible exception of Willow Creek.

During the summer of 1959 our attention was divided between the bighorn study and a survey of the water resources of Death Valley National Monument. For 4 months everything that looked like a spring, that appeared on any map as a spring, or that had been called or named a spring in a book, magazine article, scientific report, or by longtime residents of the area, was considered by us, its present status established, and its location verified and mapped.

Of the more than 300 sources entered in the Death Valley water book in 1959 (Welles and Welles, 1959), 132 were given names for the first time, 90 were mapped for the first time, and 43 were established as of prime importance to the bighorn. In the first year following the completion of that report, nearly a dozen "new" springs were described and mapped for the first time, and probably many more will follow.

But the natural water shortage which has existed throughout the region since the "little ice age" 3,000 or 4,000 years ago will continue, since it is one of time and place: Time, in the sense that rainfall is infrequent and its occurrence unpredictable; place, in that permanent sources are too far apart to permit full utilization of the forage areas between them.

There is some evidence pointing toward a gradually increasing aridity in the entire region, but whether this is a cyclic phenomenon or a long-term trend is not yet known. Changes over and above the usual erratic yearly variations in precipitation are virtually imperceptible.

Caused by Man

There is a present and perceptible danger inherent in the mining laws and their administration which has in the past allowed the complete diversion to human use of many water sources, which in turn has rendered thousands of acres of forage in former bighorn habitat unavailable, and so has become a limiting factor in distribution and survival. During the depression years scarcely a spring could be found without a prospecting camp or a "mill" site within a few feet of it, and in some places they were built directly over the water itself. Thus a shortage was created of such severity that by 1935 bighorn were believed to be practically extinct in this region. Fortunately, large numbers of these camps and mills were abandoned after the depression.

Caused by Wild Burros

It is quite commonly believed that wild burros create a water shortage by usurpation and that where burros drink bighorn refuse to water. All ecological wisdom points to the desirability of freedom from exotics of all species, and from that point of view this report adds volume to the hue and cry for drastic control of the feral burro. But in the interest of accuracy and freedom from prejudice it is urged that the issue of burro control not be joined to the bighorn issue alone.

The early summer of 1960 found the emphasis of the bighorn project once more diverted, this time to the wild burro. The results of this survey were a shock to the bighorn world. Burros and bighorn will and do water at the same springs. Burros must pollute water at times to have received such widespread condemnation for it, but this survey disclosed none of it. They do contribute indirectly and substantially to water shortages by destroying the emergency food supplies on the way to and in watering areas. The entire controversial subject of burro-bighorn interrelationship is discussed in detail under "Competitors and Enemies."

Natural

In addition to local manmade shortages owing to proximal installations or the boxing in and complete diversion of the water, natural causes may eliminate considerable amounts of water from availability. It is commonly believed that earthquakes sometimes shut off water sources, but we have no firsthand evidence of this. Floodwater, however, by burying smaller springs under tons of detrital material, has closed three known water sources during the time of this study. These three springs, Scotty's, Navel, and Hole-in-the-Rock, were subsequently restored to use by us, but the others that are lost each year and not restored are a responsibility neither accepted, delegated, nor discharged as yet by anyone.

Acceptance of New Sources

Bighorn acceptance of new or rehabilitated water installations appears to be no problem in Death Valley. During the summer of 1956 the sheep returned and used all of the rehabilitated springs within weeks of the work being done, and Lowell Sumner saw bighorn drink at Virgin Spring within the hour of installation of a new tank. One half hour after a new tank was dug at Trail Pool at Nevares Spring, a ram chased a ewe across it, and while the ewe avoided it by a tremendous leap, the ram plunged into it and immediately abandoned the chase for a long drink of muddy water.

October 10, 1955, saw the final installation of the orientation exhibit building on Dante's View. The workmen left a tub of water exposed there for the weekend and Monday morning found the tub empty and surrounded by bighorn tracks and droppings. The closest known water source is Lemonade Spring, 5 airline miles north of Dante's View. This "adaptability" to a new condition is comparatively rare compared with the "elasticity" of behavior shown by their return to former water sources that have been restored. The distinction between adaptability and elasticity will be discussed further under "Watering Behavior." Upper Willow Creek Spring is completely surrounded by a dense willow thicket wall about 20 feet deep, and the water flows through an understory cover of black sedge 2 or 3 feet high. This spring had not been used for many years when we first visited it in 1951, nor was it used until the summer of 1956. We had accepted the commonly held belief that bighorn avoid watering anywhere that their lines of vision and routes of escape are obscured, and we assumed that they bypassed this spring for the more open spring half a mile below for that reason.

On August 8, 1956, we found a band of 11 bighorn emerging from trampled-out tunnels through the willow wall, the black sedge matted down below water level as bighorn stood on it to drink. The open trails to the former watering place down canyon were deserted. This area, previously considered untenable (figs. 8 and 9), was used with apparent freedom throughout that particular dry season, but was abandoned with autumn rains. For some undetermined reason, perhaps due to a change in herd leadership, it has remained unused since. The "tunnels" have grown closed, the tall black sedge once more stands waist high, and the sheep trek half a mile farther down the canyon to drink.

On January 31, 1957, on a ridge above Echo Canyon at 4,400 feet elevation, we found a mine shaft with a partial block at the mouth from a cave-in from above caused by runoff of rainwater, which then ran back into the tunnel, filling it to a depth of about 18 inches. Old trails and droppings showed that bighorn had found the water and drunk from it. Not only had they drunk at the mouth of the tunnel, as the water receded, they had followed it back nearly 40 feet and turned a corner in almost pitch darkness to get a drink. The sign pointed to a more or less annual use of this mine shaft as a temporary water supply.

In contrast to the above records which indicate a propensity for the acceptance and utilization of water under surprisingly adverse circumstances, there is a considerable body of evidence pointing toward excessive wariness, even fear, associated with the act of drinking under what might be considered the very safest of watering environment. To mention one of many recorded examples, Raven Spring, of the Nevares Seeps, is situated in open flatland at the very terminal of a made-to-order escape route up Nevares Peak. The flat terrain and lack of ground cover would seem to preclude the possibility of ambush, and it is accepted with complete confidence by some bighorn every day. However, others approach it with obvious anxiety, and in some instances, even with terror.

Watering Behavior

To characterize bighorn watering behavior as unpredictable seems empirically safe here, but the glib postulate that the most consistent thing about the bighorn is its inconsistency should be carefully weighed. Repeated observations often present a simple answer to an apparently complex problem, and a conceivable consistency emerges here in the hypothesis that the variable individual behavior of watering bighorn should not be correlated with the environmental characteristics of an observed water source but with the experience that the individual animal has had in connection with the act of watering.

Some bighorn show signs of acute anxiety while still at some distance from water and are overcome by indecision, turning this way and that, back and forth, sometimes for an hour or more, then finally in apparent desperation dashing to the spring, where they may or may not actually drink before dashing headlong away to what seems to them a safe distance. Eventually this exhausting activity usually subsides sufficiently to allow them to satisfy their thirst, but the condition of the animals is likely to reflect their anxiety and tension in less weight and lacklustre pelage, which suggests a habitual approach to a constant problem. The problem seems to become less acute as the size of the band increases and as more stable leadership is offered, but the symptoms seem never to be completely absent until the sheep so afflicted are beyond the sight, sound, and scent of water per se, whenever and wherever found.

Some bighorn have this problem, others do not. Those that do apparently associate the mere presence of water with danger to themselves. This might be a socially "inherited" family or group fear, which can be communicated from one individual to others, possibly even over a span of more than one generation. Or it might be the traumatic experience with a predator or a poacher on the part of one individual. An accident in the spring area or a snakebite could contribute substantially to either an individual or a group fear. On two occasions we have found sidewinders (Crotalus cerastes) buried in the sand within a few inches of the position where both front feet and the muzzle of a bighorn would have been had it come in to drink at the time.

Acute fear is more likely to be evidenced by animals alone or in small groups, but this is not always true. Young rams, 2 or 3 years old and probably making the rut-run alone for the first time, almost always manifest more or less acute anxiety as part of their watering behavior, while the mature rams, from 9 years up, seem to have out grown it entirely. Some ewes with young lambs are extremely fearful while others show no nervousness whatever, approaching the spring with steady confidence, drinking leisurely, resting and browsing around the water for hours before taking an unconcerned departure. Larger bands of a dozen or more seem relatively fearless unless the water source lies in a restricted area with limited escape routes, such as Navel Spring in its box canyon with only three routes of ingress and egress. Even under these conditions some bands, having satisfied themselves as to security, will relax for a time in the shade of the cliffs.

So it appears that watering behavior among bighorn varies with the individual and is consistent only with the individual's experience with water, and therefore remains unpredictable.

Bighorn preferences as to potability of water appear to be as unpredictable as their behavior. Keane Spring, Monarch Spring, the main Nevares Spring in the Funerals, and Fire Spring on Corkscrew Peak in the Grapevines, all with running streams of potable water, are sometimes ignored while small, still, seep pools a quarter of a mile away are drained daily in hot weather. Dozens of speculations as to this behavior present themselves, but none are resolved. The same applies to questions as to why some bighorn kneel to drink and others do not; or why, in 30 days at Nevares, only 4 out of 47 sheep drank twice the same day; or why an entire herd will utilize a spring one year and abandon it the next as at Willow Creek; or why they use a source for only a few days or weeks every 2 or 3 years, as at Hole-in-the-Rock, to which the bighorn returned on September 17, 1958, for the first time since October 1956, drank the tank dry, explored the 15-foot tunnel to its end and pawed holes in the mud for more.

Individually these observations are inconclusive, but collectively they suggest an elasticity in the bighorn adaptation to aridity and in its utilization of water which is of great significance, shared only by food as a factor in the survival and distribution of the race.

Since the use of the word "elasticity" may be considered uncommon in this connection, Webster's definition of "elastic" is included here as the best description of this phase of the bighorn survival pattern: "Springing back, having the power of returning to its original form; rebounding; springy; capable of extension; having the power to recover from depression."

A separate consideration of some of the components of this definition is productive:

1. Having the [astonishing] power of returning to its original form.

Our reports prior to the summer of 1957 contain many references to the relative physical condition of animals observed. During the 30 days at Nevares we finally became aware of a correlation between apparent physical condition and the temporary degree of dehydration of the animal at the time of observation. The word temporary is scarcely adequate to emphasize the dramatic quality of the change that occurs in the dehydrated bighorn both during the ingestion of water and in the period of rehydration of the body which follows. We often witnessed a metamorphosis so complete that is was difficult to believe that the animals leaving the spring area were the same as we had seen approaching it.

For example, at 8:45 in the morning of August 16, 1957, with the temperature already at 100°, an emaciated ewe and lamb stood at Old Spring and drank for 11 minutes. Their pelage was rough and dull, their legs spindly with knobby joints and taut, stringy muscles. Hip bones, ribs, and skulls lay close under drawn and shriveled skin.

We wondered aloud as we watched them drink: What caused this forlorn condition? Was it some illness? Lung-worm? Not enough food? Not the right kind of food?

As they drank their sides filled out, then began to protrude until by the time they had finished drinking and sought shade for resting there was a pathetic incongruity between the distended bellies and the shrunken limbs of the animals.

The ewe nibbled briefly at desertholly as she moved slowly toward the shade of a mesquite, but the lamb seemed too full, walking slowly with its legs wide apart. A half hour after drinking they left the shade and began the grueling climb up the face of Nevares Peak.

There was nothing unusual about what they were doing; we had watched it many times—routine watering behavior of a bighorn ewe and lamb at a desert spring in the summer. What had happened to them in the last few minutes was also normal routine. I had seen it before, many times; another such instance involving three animals has been described in "Amounts Taken" under "Water." But somehow it had never before fallen into place. Now it did. I was watching the ewe and lamb climb, briskly, easily, in the gathering heat, and I was marveling at how two animals in such poor condition could do this when I suddenly realized that they were no longer in poor condition! The potbellies were gone, the legs were no longer spindly, and the muscles were smooth and rounded beneath the glistening hides of animals in perfect health. Now I suddenly realized that the apparent emaciation of their bodies when they had first appeared at the spring half an hour before was a symptom, not of bad health, but of acute dehydration. This rapid recovery from it, this complete rehydration in so short a time seemed little short of miraculous when observed in full context and relativity. It is one of the most significant single observations we have made, since we have come to believe that without the possession of this extreme physiological elasticity there would probably be no desert bighorn as we know them today. Once noted, the metamorphosis, the "miracle at the spring," was recorded many times.

The next morning, August 17, we recorded a young ram, also shriveled like a dried prune, standing drinking at Raven Spring. This time we consciously watched for it for the first time—the filling out of the tissues of the body, very much as the dried prune would fill out if dropped in a glass of water. At first just a highly inflated look as he drank time after time—but within half an hour he was no longer potbellied but smooth and straight in the body. His hind quarters were filled out and rounded, his neck no longer stringy looking—slim to be sure, but rounded and sleek.

Gauntness is commonly associated with dehydration in all animals, but in these other animals the shrinking of muscles to such an extreme scrawniness of the limbs and neck and a general skeletal protrusion, as well as the apparent dullness and roughness of pelage, usually ascribable to malnutrition and disease, is not associated with an ability to recover promptly, easily, and almost routinely as with the bighorn. The camel of the Sahara Desert does equal or possibly surpass the bighorn in this respect, for it can lose more than 25 percent of its body weight through dehydration without being seriously weakened. It exhibits a similar emaciation on being deprived of water and a comparably dramatic filling out of the tissues about 10 minutes after drinking (Schmidt-Nielsen, 1959). Whether bighorn possess insulation, and body temperature tolerances, of the same magnitude is unknown, but it would appear likely that the mechanisms are comparable. The shrinking of body tissues and shriveling of the skin are considered symptomatic of a fatal or near fatal degree of dehydration in the human body (Adolph, 1947). Park rangers at Death Valley have observed a similar shriveled appearance, followed by a rapid transformation to near normal, in persons whom they have rescued from near fatal dehydration. In man, under desert conditions, a loss of 12 percent of body weight through dehydration is fatal.

2. Having the power to recover from depression.

All evidence points toward the economic depression of the thirties as an even worse depression for the bighorn of Death Valley. in that scarcely a water source existed during that time that was not usurped by mining interests which not only robbed the sheep of their water supply and the forage made available by it but raised poaching to a significant volume for the only time in the known history of this region.

The recurrent droughts (such as the 18 months during 1955—56) reduce the standard of living for bighorn to a depression status from which they regularly recover. We realize that other species in different environments from that of Death Valley likewise show great elasticity in population recovery. Deer afford a good example.

3. Being capable of extension.

At Raven Spring, 10 a.m. on September 10, 1957, a full curl ram (Broken Nose) drank his fill and went into the shade of Red Wall Canyon, half a mile north of the spring. At 11:20 another full-curl ram (Tabby), dull-coated, lame, and generally emaciated in appearance, was hustling toward the spring when Broken Nose arose from his shaded siesta and challenged him. Tabby, who either had had no water for 42 hours (September 8 at 4:30 p.m.) or had just finished an 8-airline-mile trek through the mountains from Indian Pass on a day when official temperature was 113° in the shade, met the challenge and fought his well-rested, completely rehydrated opponent for 2 hours with no apparent handicap and at no discernible disadvantage whatever.

Each charge of a battling ram entails the expenditure of a tremendous amount of energy. The adversaries stand from 15 to 40 feet apart, rear, and on their hindlegs race toward each other to the proper point, then, with every ounce of energy they can muster, hurl themselves through the air and meet head on at a speed in the neighborhood of 30 miles per hour (Cottam and Williams, 1943). A few minutes recovery time may be allowed or it may not. Tabby and Broken Nose blasted each other something over 40 times in 2 hours. Ten minutes after the fight had ended in a draw, Tabby came in to water and drank for 12 minutes, ate a few mouthfuls of grass, and went into siesta until 5:45, when he went back to the spring grasses and grazed until 6:30. Then, having last drunk 5 hours before, he headed into the South Wash, sleek and fat, walking briskly and rapidly in 102° of heat.

On August 17, 1957, with the official maximum temperature at 122°, Buddy [Mrs. Welles] spotted two pale bighorn racing across the foot of the mountain three-fourths of a mile to the north. I estimated their speed at 25—30 miles per hour through terrain that we could scarcely walk across with safety.

As they raced nearer, with only the briefest hesitations in their head long flight, it became evident that it was a ram chasing a ewe. As they came opposite us, the ram (a young one, 3 years old) lunged at the ewe's flank with his horns, and they put on an incredible burst of speed which ended only at Long Spring a quarter of a mile from us.

They drank for perhaps 10 minutes. Then, bulging with water, they began the chase again. The ewe started to run toward the mountain, and the ram headed her off, turning her back toward the spring. She tried to go around him on the other side. He turned her back like a cutting horse working with cattle, or a sheep dog with sheep.

She tried to get away half a dozen times, but he ran faster, lowering his horns and forcing her to stop and turn back.

Then suddenly, as though by common consent, the activity ceased as abruptly as it had begun. The ram sought shade on one cliff and the ewe another, leaving us to put our cameras away gratefully, for by now they were almost too hot to touch, since our wet-bath-towel cooling system had long since stopped functioning.

What we had been observing was a phase of mating activity which we were to record again and again. One such incident lasted for 3 days with no apparent depletion of energy on the part of either animal, although as far as we could determine they had no water during the entire time.

Their ability to extend their energy to incredible limits is put to what is probably its severest test when a band already severely dehydrated reaches a water source to find that it is no longer available. When this happens, their willingness and ability to extend their expenditure of energy to the ultimate inclusion of another water source within the limits of their home area may be one of the principal reasons that they have outlived so many contemporaries of 11,000 years ago.

The above observations are made more significant by the total absence in other forms of desert life in the Southwest of such strenuous and prolonged activity in excessively high temperatures.

A Factor in Distribution and Survival

Too much emphasis can hardly be placed on the importance of their use of food and water as factors in the distribution and survival of the bighorn. In the violated ecology of the Death Valley region, their hardiness has been amply proved, but human encroachment, with its attendant results, is the denominator of eventual destruction unless its pressures can be kept from increasing each year.

The elasticity described above should not be confused with adaptability or flexibility, since we could not support a very strong claim for either in the bighorn. With the exception of occasional prompt use of new water sources discussed previously, evidence points toward a prevailing inability to make quick adaptation to a major change of environment. The mortality ratio from shock also runs high in most efforts to transplant bighorn from one area to another. The wild burro, on the other hand, seldom injures himself in captivity and has never been known to suffer from shock, much less die from it (Welles and Welles, 1960).

Flexible means easily bent, pliant, yielding to persuasion—characteristics not yet noted in the bighorn.

And, finally, it must be emphasized that this elasticity which we have considered so thoroughly here is limited to the conditions of their natural habitat and to the uninhibited employment of all their instincts for survival.

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Thurs, May 16 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/fauna6/fauna2c.htm

![]()