|

Effigy Mounds

Administrative History |

|

Chapter Two:

EURO-AMERICAN USE OF THE REGION

Although their presence in the area is undocumented, French coureurs des bois (unlicensed traders) were the first Europeans to enter northeastern Iowa to trade for furs with local Indians. The brothers-in-law Pierre Esprit Radisson and Medard Chouart des Grosseilliers may have returned to the Great Lakes from the interior via the Wisconsin and Fox rivers in 1660. The traders' failure to record their whereabouts may have resulted from fear of punishment for their extralegal activities, or they simply may have believed such documentation unnecessary. Whatever the reason for the lack of official records, the land which became Iowa was well—integrated into the French fur trading network long before it officially became part of New France.

The first Europeans to record their explorations in the region were Louis Joliet and Father Jacques Marquette, who, with five companions, paddled their canoes out of the Wisconsin River and onto the Mississippi on June 17, 1673. In 1680, Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, built a trading post in the approximate location of modern Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. La Salle was trying to establish a monopoly of the Mississippi River fur trade. His chief competitor was Daniel DuLuth, who, after rescuing some of La Salle's employees from the Sioux farther to the north, had traveled down the Mississippi to the mouth of the Wisconsin and thence to the Great Lakes. [1]

The French fur traders dominated the area for the next century. One key early figure was Nicholas Perrot, who in 1685 established Fort St. Nicholas on the Prairie du Chien terrace. Within a few years his employees penetrated well into Iowa, trapping and trading with the Indians. Perrot was active along the upper Mississippi River until the early years of the eighteenth century. He established several forts at various locations. [2]

Perrot's first post at Prairie du Chien became a center of the French fur industry and the principal place for the "grand encampments," the rendezvous where traders and Indians came to dispose of their furs and outfit for the coming trapping season. In time, some of the bourgeois, the major traders, and other Frenchmen married Indian women and established families at Fort St. Nicholas. Indian villages settled there on a permanent basis, and the Prairie du Chien terrace became an important place on the Mississippi River, ranking with Green Bay and Michilimackinac on the Great Lakes as a center of the fur trade. Subsequent occupants built a succession of trading forts on the site to take advantage of that trade; the last known of the trading posts was built circa 1755. [3]

There were sizeable numbers of French adventurers in the Mississippi valley. In 1680, when the French government granted amnesty to any coureur de bois who "came in" out of the western forests, no fewer than 600 surrendered themselves to French authorities. Many of these illegal traders operated in the fur-rich region near the effigy mounds. The 1700 deLisle map of New France shows a chemin du voyageurs penetrating deeply into Iowa, and deLisle's 1703 map shows the same traders' road starting about where McGregor is today and extending to Lake Okoboji and Spirit Lake in northwest Iowa. By 1738, Pierre Paul Sineur Marin, whose sphere of influence in that year encompassed the region around Prairie du Chien, built a trading fort at the mouth of Sny Magill Creek to gain the trade of the Sac, Fox, and Winnebago tribes, then resident in part on the west bank of the Mississippi, and to provide a check on the Sioux marauders who terrorized Iowa. [4]

Despite the numbers of French occupants and the length of their stays, their records contain no references to the effigy mounds in the area where the national monument is now located. The French occupants were undoubtedly aware of other types of mounds, for there were large conicals on the Prairie du Chien terrace and nearby. Hunters probably crossed the river and climbed the northeastern Iowa bluffs, but either they never noticed the effigy mounds there or never thought them worth comment. [5]

Although there seemed to be many changes in the fur trade after 1763, most of the changes were more apparent than real. Following the French and Indian War, Britain replaced France in authority on the east bank of the Mississippi, while the Spanish assumed control of the west bank. For a while, the British tried to force traders to work out of one of their military posts; however, there were no British military forts on the upper Mississippi River, and the Indians were not inclined to travel through enemy territory to reach British posts on the Great Lakes. Further complicating the matter, Spanish authorities claimed all the furs taken west of the Mississippi River and sent a great many traders upriver from St. Louis to ensure that Spanish furs did not fall into British hands. The Spanish traders often stopped at the Prairie du Chien trading posts, and friction between traders of different national origins was not unusual. The British responded to the threat posed by Spanish inroads into the fur trade by reopening the business to independent operators, thus restoring the old French practices. Most of the traders, their agents, and sub—agents were the descendants of the same Frenchmen and half-breed metis who had dominated the trade during the preceding century of French control. Finally, because there was no authority to enforce it, the international boundary was generally ignored. [6] All of these factors prevented any substantial differences in use of the area under British control.

The basis for Prairie du Chien's continued importance was (and is) topographic, for the Prairie du Chien terrace is two miles wide and more than seven miles long. It controls both the Mississippi and Wisconsin rivers, dominating the major east—west trade route as well as the north—south artery. By contrast, the largest terrace on the Iowa side, Harpers Ferry, is a bit less than two miles square and does not adjoin the Wisconsin River. Other river terraces on the Iowa shore are even smaller and the rest of the terrain is rougher than on the east bank. [7]

Still, it was not unusual for parties of traders, and presumably Indians as well, to occupy semipermanent sites on the west bank of the Mississippi. The traders with whom Massachusetts surveyor Jonathan Carver traveled from Michilimackinac in 1766 established their winter quarters on the Yellow River, possibly within the boundaries of the national monument. Similarly, Peter Pond's first camp in the Mississippi River valley in 1773 was on the Iowa shore. [8] Since their camping across the river from the village aroused no comment, it is probable this was a common occurrence.

The Revolutionary War had slight effect on Euro-American use of the upper Mississippi valley. Britain used its network of traders to recruit native warriors for the fighting; for example, a party of Sac and Fox took part in Burgoyne's invasion of New York and in the battle of Saratoga in 1777. Throughout the war, the British kept enough gifts and trade goods flowing to retain most of the Indians' loyalty.

The Spanish also maintained their presence in the area and tried to win the tribes' allegiance for themselves. After Spain declared war on Great Britain in 1780, the British mounted an unsuccessful expedition against St. Louis with a force of Indians led by English and Frenchmen. In a counter-stroke, a party of Americans occupied Prairie du Chien after its evacuation by British adherents. [9] The struggle in the west was primarily between Britain and Spain; the key issue was control of the fur trade. Apparently, most of the tribes were emotionally inclined to favor the Spanish, who were seen as heirs of the French traditions and were more open—handed in their trading. In spite of the Indians' emotional ties to the Spanish, however, the tribes were economically dependent on the British, who could better supply their needs. A scattering of American agents sought to gain for their new nation the neutrality, if not the active support, of the Indians. In spite of limited budgets and the relative lack of power of their government, they were relatively successful. [10]

After the Revolutionary War an enterprising American, Basil Giard, took advantage of Spain's ownership of the Iowa shore by applying for a land grant there. On November 20, 1800, Lieutenant Governor Don Carlos Dehault Delassus of Upper Louisiana granted to Giard a tract of about 5,760 acres in present-day Clayton County, just to the south of Effigy Mounds National Monument but encompassing the future sites of Marquette and part of McGregor, Iowa. This northernmost of the Spanish land grants, the third and last granted in Iowa, extended for one and a half miles along the Mississippi River and six miles inland. Giard established a "trading center" on his claim, which remained active from 1796 until 1808. One on the stipulations in his land grant charged Giard to

. . . help with all the means in his power the travelers who shall pass his house, as he has done hitherto, and to preserve a good understanding between the Indian Nations and [the Spanish] government, as well as to inform [the government in St. Louis] with the greatest care of all the news which he shall gather. [11]

This stipulation did not preclude his engaging in a little casual trading, and may even have encouraged it as a means of maintaining good relations with the Indians. In 1805, only two years after the United States purchased Louisiana, the government confirmed Giard's heirs as legal owners of the land grant. Part of the grant was sold "to two early settlers" by 1808. [12]

After the Revolutionary War, the Jay Treaty allowed joint American and British exploitation of furs in the region, which resulted in continued British control until after 1800. The only "American" company, the Michilimackinac Company, was owned by Montreal traders whose "competing" North West Trading Company for a time occupied a trading post on the Yellow River. This was well upstream from the national monument and was blatantly illegal, as the land west of the Mississippi was under Spanish control. There were no genuine U.S.—owned companies in the region until John Jacob Astor formed the American Fur Trading Company in 1808. [13]

Rivalry between British and American traders, quite keen after the Revolutionary War, intensified after the Louisiana Purchase eliminated competition from the French and Spanish. One of the key reasons for Zebulon Pike's 1805 journey of exploration was to ascertain the amount of British influence among the Indians of the upper Mississippi River valley. Pike found that almost all of the trade there was controlled by British agents. He spent considerable time during his journey trying to turn the Indians' allegiance from Britain to the United States. Pike also warned British traders and Indian tribes to stop flying the British flag in American territory. [14]

Relations continued to worsen until they erupted in 1812. At that time the Americans, outraged over British incitement of the Indians in the upper Mississippi basin, erected a log fort "of no great pretensions" on St. Feriole's island in what is today Prairie du Chien. [15] The Americans held this fortification, named Fort Shelby after the governor of Kentucky, for just over one year. The army completed construction of Fort Shelby in June 1813; on July 20, 1814, the British captured it and renamed it Fort McKay in honor of the British commander who led the attack. The Treaty of Ghent forced the British out of the Old Northwest and Fort McKay was burned, either by the British as they evacuated or by Indians soon afterward.

In 1816 a party of Americans under Colonel William Southerland Hamilton built Fort Crawford, named for the Secretary of War, on the same site. This proved a poor location as the rising water each spring flooded the place, sometimes so severely as to force its evacuation for weeks at a time. However, a parsimonious Congress refused to authorize funds for a new fort for thirteen years, by which time repeated immersion had rotted the old one beyond hope of repair.

The Fort Crawford military reservation, much larger than the fort itself, extended to the west bank of the Mississippi where it included a large part of what became the south unit of the national monument. Whether the land west of the river was part of the initial reservation in 1813 or was added in 1816 with the establishment of Fort Crawford is unclear; the earliest known maps show the military reservation beginning at the northern edge of the Giard grant and extending at least to what is today the Allamakee-Clayton County line. [16]

Jonathan Carver of Connecticut was the first known American colonist to visit the vicinity of the national monument; he did so in 1766 while exploring Britain's newly-acquired Northwest Territory. Both he and Peter Pond, who arrived in 1773 to engage in the fur trade, reported seeing numerous mounds. Neither of them mentioned effigy—shaped mounds however. Apparently neither of them climbed the bluffs in what is today the national monument. Carver described the tumuli at Prairie du Chien as well as elaborate series of mounds further north but he, like Pond and some later explorers, thought they were old pre-Indian fortifications. [17]

Similarly, there is no record that Zebulon Pike explored the area of the national monument during his 1805 journey. He or his men may well have done so, for the party spent several days at Prairie du Chien, and he was searching for a site for a fort in that vicinity. He scaled the elevation locally known as "Pike's Peak," which is opposite the mouth of the Wisconsin River and only three and one—half miles south of the monument. Many things Pike and his men saw was unreported; the journal Pike kept of his travels on the Mississippi River was, at best, a terse record. In general, he noted only events that directly related to his orders; because he was not directed to inspect aboriginal mounds, effigy-shaped or otherwise, he did not mention them in his journal. Pike certainly knew of mounds, for the two sites he recommended as locations for a trading post and a fort were covered with mounds, including one rather well-defined bear effigy at "Pike's Peak." [18]

Maj. Stephen H. Long of the Army's Topographical Engineers, another early nineteenth century explorer, made two journeys through the effigy mounds region, and his journal frequently mentioned the great number of tumuli he encountered. Long described conical, linear, and combination mounds, all of which he mistakenly identified as defensive fortifications also used for burials. He mentioned only one effigy mound, that of a dog, in what is today Ontario, and which was described to him (he did not see it himself) during his 1823 expedition. "The figure is no longer discoverable," Long wrote in his journal. "It was constructed of earth after the manner of the figure of the same animal. . . . It is said to have been made by a war party of Sioux, who are accustomed to similar practices." [19]

During the same 1823 expedition, Long and five other members of his party landed on the Yellow River about one and one—half miles above its mouth and from there proceeded on horseback to the site of today's Minneapolis-St. Paul. The expedition stayed to the west of the national monument, but their route, which crossed the upper Iowa River four miles above its junction with the Mississippi, certainly took them across an area where effigy mounds existed. Still, Long's journal for this part of the expedition, while remarking on "numerous and crowded" mounds, makes no mention of effigies. Long simply may have overlooked the effigy mounds, which were not as tall as the conical and linear mounds he came across. [20]

Henry Schoolcraft's observations were much like those of Stephen Long, although Schoolcraft, traveling almost entirely by canoe, noted far fewer mounds than Long did. In fact, in describing one formation near present—day Minneapolis Schoolcraft quoted Carver's description, as Schoolcraft himself did not go ashore to examine the structure. Like Carver and Long, Schoolcraft thought the mounds were defensive works, and while he did not try to establish a connection, he reported an Ojibway story about one band of warriors who, during historic times, used rifle-pits and mounds of earth while fighting their mortal enemies, the Sioux. Schoolcraft, like the other explorers, did not mention having encountered effigy-shaped mounds. [21]

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities between the United States and Great Britain in 1812, the U.S. government recognized the need to control the upper Mississippi River basin and its native people. Indian apostasy during the war added further proof of the need for control, and restoration of U.S. sovereignty by the Treaty of Ghent afforded the opportunity. The government established a chain of forts along the Mississippi River soon after the war, stretching from Fort Jessup, Louisiana, to Fort Snelling, Minnesota. The forts served several functions. They were the visible symbol of the government's authority for both white and red men, and usually they were the only law enforcement body for many miles. [22]

Fort Crawford, built in 1816 on the floodplain where Fort Shelby had stood, was one of the major links in this chain. Unlike most of the other posts which were built in the wilderness and subsequently became the nucleus of urban settlement, the army built Fort Crawford at an existing town. The fort contributed to the area's growth, both because of the security provided by the troops, and because of the services required by the military people stationed there. Besides the obvious grog shops and "easy women" catering to the soldiers, the post required large amounts of grain, hay, and firewood. Some of this was provided by troop labor, but the rest had to come from the surrounding community, or by boat from St. Louis. The army also consumed large quantities of vegetables, milk, and fresh beef, pork, and fish, thus providing a market for local entrepreneurs. The soldiers, in their turn, explored and surveyed the surrounding countryside, built roads and bridges, and provided social services not otherwise available. As an example, an English language school opened in Prairie du Chien in 1817. Sgt. Samuel Reeseden served as teacher; he also operated the post school. [23]

As mentioned above the post was poorly sited; floods often forced its evacuation. The site was unhealthy and the fort itself "wretched." During his inspection of the post in 1817, Stephen Long thoroughly scouted the Wisconsin shore for a better location, but none could be found. Apparently Pike's recommendation of the heights on the Iowa shore as the best site had been rejected at some higher level of command, for Long, according to his report, did not consider the western side of the river as a possible location for a new fort. [24]

In 1825 the U.S. government called for a Great Council of Plains and Woodland tribes to meet at Fort Crawford. The government hoped to put an end to the continuing wars between the tribes by establishing a distinct boundary between them. The Sioux arrived first, and occupied the Prairie du Chien terrace. Other tribes, notably the Sac and Fox and some Ioway, camped on an island in the Mississippi and on the Iowa shore in the valleys where McGregor and Marquette are today, and possibly in the Yellow River valley as well. The tribes hunted game in the area now occupied by the national monument.

After much bickering, the government drew a line separating the Sioux on the north from the Sac and Fox to the south. This line started at the mouth of the upper Iowa River and ran west—southwest to the junction of the forks of the Des Moines River and beyond. Unfortunately, the political boundary failed to prevent clashes between the traditional enemies. At the time, however, hopes for peace were high enough and the condition of Fort Crawford was bad enough to encourage the army to abandon Fort Crawford and transfer the troops to Fort Snelling. This situation lasted for one year, during which outbreaks by the Winnebagos and other tribes convinced the army to reopen Fort Crawford in 1827. [25]

In 1830 another peace council was convened at Fort Crawford. It established a forty-mile-wide strip, twenty miles on each side of the line drawn in 1825, of "neutral ground" as a buffer between the hostile tribes. This neutral zone lay to the north of what is today the national monument. Sadly, it was no more successful in preventing intertribal warfare than the 1825 line had been.

In 1833, after the Blackhawk War, the government tried to solve two problems at once by settling the displaced Winnebago in the eastern forty miles of the neutral zone as a buffer between the traditional enemies. The government hoped to keep the Sioux separated from the Sac and Fox, and also get the Winnebago out of Wisconsin. This plan was no more successful than its predecessors.

At roughly the same time the federal government forced the Sac and Fox to give up a fifty-mile-wide strip in eastern Iowa extending from the Missouri border to the neutral zone. "Scott's Purchase" or, as it was later called, the "Blackhawk Purchase" was the nucleus of the state of Iowa. It included the area that later became the national monument. [26]

|

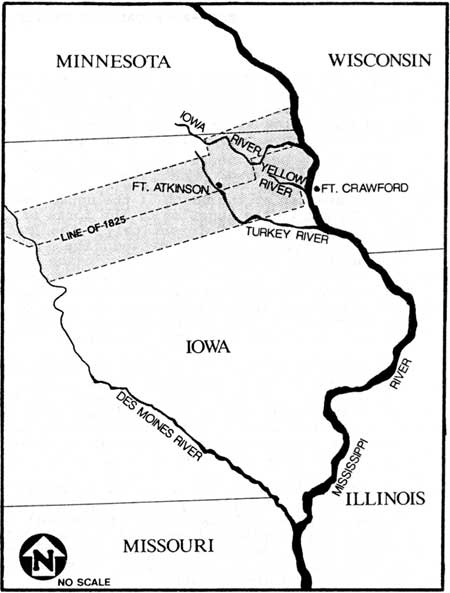

| Figure 2: The neutral zone, 1830. |

Between the 1825 and 1830 peace councils, Congress had authorized construction of a new Fort Crawford, and Post Commander Bvt. Maj. Stephen Watts Kearny selected a site for it above the Mississippi's high water mark with "tolerably good" access to the river. Construction of the new fort required timber, and by 1829 Capt. T.F. Smith opened a sawmill at the first rapids on the Yellow River about three and one-half winding miles above that river's junction with the Mississippi, just outside the national monument's current boundary. [27] The army cut oak trees from the bluffs and ridge tops along the Yellow River, sawed them at the mill, and rafted them down from the Chippewa River where they were sawn. The government also owned land south of the Yellow River; the so—called "Post Garden Tract" provided timber, firewood, and garden vegetables for the fort. Lime for the stone construction and for whitewash was burned where McGregor now stands. [28]

In 1830, a young lieutenant, Jefferson Davis, arrived at the fort from Green Bay. The following year he was charged by post commander Col. Zachary Taylor to take charge of the sawmill. [29] Tradition holds that Taylor sent Davis across the Mississippi River to superintend the sawmill in order to break up a budding romance between his daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor, and Davis. If that was Taylor's intention, it did not work: Jefferson Davis married Sarah Taylor in 1833. [30]

During his 1817 inspection of the post, Major Stephen Long noted that most of the buildings at Fort Crawford were "floored with oak plank" and the top story of the blockhouses were "fortified with oak plank upon their sides," but Long failed to state whether these plank were sawn or hewn. There are indications that some of the materials for the earlier structure came from the area which is today the national monument, for Long also commented that timber and stone for construction of the first fort had to be "procured at the distance of from 2 to 5 miles from the site of the Garrison and transported to it in boats," and describes the countryside where the timbers were procured as being "so broken & hilly that teams could not be employed even to convey them to the boats but all must be done by manual labor."

One of the clauses of the treaty ending the Blackhawk War provided that the United States would erect a school with an attached farm in the vicinity of Prairie du Chien for the benefit of the Winnebago Indians. The Winnebago were to occupy a reservation composed of the eastern—most portion of the forty—mile wide "neutral zone" established by the council of 1830. In 1834 the Indian agent let the contract for the construction of the school and farm on a site three miles north of the "Jefferson Davis sawmill" on the Yellow River. It is unclear whether the sawmill, no longer needed for construction of the fort, was transferred by Colonel Taylor to Indian Agent Joseph M. Street, or (more likely) Taylor simply gave Street the sawn lumber needed to build the complex. Whichever was the case, the Winnebago Yellow River Mission School and Farm was constructed with lumber from the mill. In fact, shortly after Street let the contract for construction of the mission, he was transferred to Rock Island, Illinois, leaving supervision of the construction and of all public property in Colonel Taylor's reluctant hands. Upon completion of the Yellow River mission buildings (and perhaps to prevent similar problems in the future), Taylor ordered the machinery removed from the sawmill and abandoned the mill structures. A few years later, they burned to the ground. [31]

Some years later the soldiers built (or improved) [32] a road across what is today the south unit of the monument. They used the military road to facilitate the construction of, and later for communication with, Fort Atkinson in modern Winneshiek County, Iowa. [33] Most accounts agree the military selected the route without civilian assistance and constructed the road with troop labor. [34] A tremendous amount of pick-and-shovel labor was required to build the road from the ferry landing to the bluff tops. The most readily available source of that much manpower was the army. The road also facilitated transfer of produce from the post gardens, as well as hay and firewood from that portion of the reservation located on the Iowa shore. [35]

From 1840 on the military road, upon reaching the bluff-tops, curved around the ten bear and three bird effigies that compose the Marching Bear mound group in the southern end of the national monument's south unit. In one place the road runs very closely along the back of one of the bear mounds, and it cuts off the tail and the tip of one wing, and part of the tail of the two southwestern-most bird mounds of this group. A spur from the military road that leaves the main branch about two—thirds of the way up the ravine and then ascends the opposite side reunites with the main road at the wingtip of the southwestern-most bird effigy. Still, there is no mention of effigy—shaped mounds in any reports on the construction or use of the road. It is possible, though unlikely, that the effigies went unnoticed by everyone concerned, for the mounds are rather low in relation to their size. They average two feet or less in height, and are roughly eighty feet long and forty or more feet wide. They were, therefore, not as readily visible as some of the taller conical and linear mounds. The builders may have noticed that there were mounds in the area, but failed to note their effigy shapes. Certainly everyone at Fort Crawford knew about Indian mounds, for they were prevalent on the Prairie du Chien terrace and elsewhere throughout the area. In fact, the army leveled a large conical mound when building the new fort, and contemporary accounts tell of cartloads of bones being taken from the site. Further, there are several historic military burials in a prehistoric conical mound. Perhaps mounds were so common that no one thought them worthy of comment. [36]

The government wagons then in use were each pulled by six mules controlled by a driver riding the nigh, or left front mule and using a jerk-line. [37] In addition to military wagons, contractors, traders, and an increasing number of emigrants used the military road to get to the top of the bluffs. On any given day there were horse and ox teams of varied sizes and all types of conveyances interspersed among the military mule teams, all climbing up the road to the top of the bluffs. The army was the primary user of the road until mid-1848, when the Winnebago were removed again, this time to Minnesota. Military traffic continued for a brief time after that, but in February 1849, the troops left Fort Atkinson for the last time, and by the end of May the army abandoned Fort Crawford and the road. Pioneers moving to land farther west and other civilian traffic continued to use the old road until about 1860. Those who had settled on the ridges to the west used the road to move their grain to the river for shipment to market. [38]

Concurrent with the building of Fort Atkinson, civilians under contract with the army erected a large building at the. Smith's Landing. The building stored supplies until wagons were available to transport them to the new fort and Indian agency. About the same time, the government constructed stables and a wagon shed.

There is no indication of °ree;permanent troop or civilian residence at Smith's Landing, but there is a long record of at least semi—permanent settlement on the Iowa shore beginning with Carver's and Pond's companions, referenced above. Occupation and use of the west bank continued into the nineteenth century. [39]

One sojourn in the Yellow River valley ended with the first recorded murders within the boundaries of the national monument. In March 1827, Francis Methode, with his pregnant wife and seven children, camped on the Yellow River [40] while making sugar from the maple trees there. When the family failed to return in a reasonable time, a party of their friends searched for them. The searchers found their camp burned and all family members so badly mangled and charred that the causes of death could not be determined. However, the family dog was found nearby, his body riddled with bullets, and a piece of scarlet cloth clutched in his teeth. Because the cloth was of the type used by Indians for leggings, the searchers concluded the family was killed by a party of Indians, probably Winnebago, since Winnebago tribesmen killed several settlers near Prairie du Chien about the same time. Oddly, two other white women, one other white man and two Indian women living near the Yellow River at the time were unhurt by the murderers. These last five people were apparently permanent residents of land now within the national monument. [41]

Alexander McGregor, who acquired a part of Giard's claim and established a ferry terminal known as McGregor's Landing (also known as "Coulee de Sioux"), [42] one of the earliest recorded landowners in Iowa. Sometime before 1840, McGregor came into ownership or use of some warehouses, wagon sheds, and stables located on the land. Whether anyone lived permanently on the Iowa shore is questionable. Until 1832, all of northeastern Iowa except Giard's grant and the Fort Crawford reservation was Indian land; the area was not surveyed until 1848. Further, until 1848, the area was shared by the Winnebago reservation, which precluded settlement by Euro—American pioneers. [43] The Winnebago frequently left the reservation, either to return to their former territory in Wisconsin or to roam around the Iowa countryside. Although they committed few serious depredations, settlers remained extremely uneasy and the soldiers were kept busy rounding up stray bands of "escaped" Winnebago. [44]

|

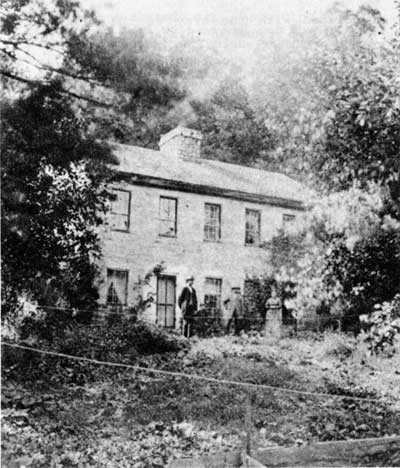

| Figure 3: The Winnebago Yellow River Mission School and Farm, circa 1840. Photographer unknown. Negative #6 (O-772), Effigy Mounds National Monument. |

There were a few white men in the area. Some staffed the Winnebago mission as early as 1835, and after 1841 the replacement Winnebago Mission School and Farm had a staff of more than twenty. In 1837, Henry Johnson took up residence on Paint Creek. The first known white child to be born in northeastern Iowa was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Rynerson, born at the old Yellow River Mission in 1841. Nevertheless, there were very few settlers in the Effigy Mounds area. Other than those associated with the army or the mission, no white farmers plowed the ground in this area until May 15, 1850. [45]

One of the earliest recorded settlers in Allamakee County, albeit not on national monument land, was Joel Post. A millwright from upstate New York, in 1841 the army permitted Post to occupy the house and stable it had built on the military road, halfway between Forts Crawford and Atkinson. As a condition of his residence at Halfway House No. 1, the government required Post to take care of the buildings and make them available to travelers. The permit stated:

the use of the buildings [is] to be always open, free of charge to the use of the public; a supply of wood for the use of one fire is also to be furnished free of charge. The said Post will also be required to take charge of and be responsible for all public property placed under charge at that place. [46]

In 1843, Post built Halfway House No. 2 on a shortcut on the military road. [47]

Two early entrepreneurs who established businesses about fifteen miles southwest of the modern monument deserve brief mention. These were Taffy Jones, who established a "resort" just outside the Indian Reservation boundary in about 1840, and Graham Thorn, who started a rival establishment about a furlong away the following year. Jones' business was nick named "Sodom" by the area soldiers who doubtless knew it first hand, so Thorn christened his establishment "Gomorrah," in keeping with the tone already set. According to contemporary accounts the resorts were well—named, but both places quickly faded into obscurity after the Indians and troops were removed in 1848—49. [48]

Most early Iowa immigrants passed over the land now comprising the national monument, probably because the land there was too rough to encourage farming. True, the ridge tops within the monument were tillable, but most potential settlers went farther west, where stream valleys were shallower and slopes less abrupt. The ridges were predominantly covered with prairie grass, and contemporary farmers believed land that would not grow trees should not be expected to grow crops. Much of the land in the present national monument was acquired for speculative purposes by prominent citizens of Prairie du Chien; McGregor, Brisbois, Lockwood, Dousman, Rolette, and Miller are named for early landowners on the Iowa shore. Still, there were other scattered early squatters in the area, even before the government survey. The Methodist circuit-rider stopped regularly at the Yellow River mission (which was Presbyterian) during the 1830s, and the Baptist Church counted eleven members during the same period in present—day Allamakee and Clayton Counties. [49]

|

| Figure 4: Mrs. Zeruiah Post assisted her family in managing the so-called "Halfway Houses" along the military road between Forts Crawford and Atkinson. Photographer and date of photograph unknown. Negative #9 (O-780), Effigy Mounds National Monument. |

|

| Figure 5: A.R. Prescott's ca. 1852 sketch of one of the Halfway Houses depicts a woman, probably Mrs. Zehuriah Post, on the front porch. Negative #8 (O-779), Effigy Mounds National Monument. |

There are no indications that northeastern Iowa differed significantly from the rest of the state in patterns of settlement, size of farms, or crops produced. After the area was opened to settlement, the pioneers tended to locate in wooded areas or on their fringes, both for protection from the elements and for ready access to building and fencing materials and firewood. Most working farms were about forty to one hundred acres, a size that could be managed by one family. There were larger units, most notably that of a man named Laird, who during the latter part of the nineteenth century owned more than 1,000 acres. Laird built his home about where the national monument residences are now located. Most farms in the area seem to have been held by the same family for one or possibly two generations, although there are landholdings that stayed in the same extended family for a century or more. At the other extreme, during the early years of settlement, some parcels of land changed ownership at least every years.

By the third quarter of the nineteenth century, there were fewer than a half—dozen farmhouses on land that became the national monument. They were situated at the site of the present headquarters, in the south unit on the west side of Rattlesnake Knoll, in Sawvelle Hollow, and possibly at the mouth of the Yellow River on the south side in the townsite of Nazekaw (also spelled "Nezeka"), which was platted in 1856. Prairie du Chien entrepreneurs B.W. Brisbois and H. Dousman promoted settlement of Nazekaw, which included a post office between 1858 and 1862, a stockyard, and a steam-powered grist mill there for some years. [50]

In general, farmers tilled only the tops of the bluffs and all but the smallest terraces along the rivers. They used steeper slopes for grazing the few semi—wild hogs or cattle. The first crops grown were usually corn or potatoes and garden vegetables, but as soon as possible (usually by the second year), every farmer tried to grow some wheat for sale. Wheat was the primary cash crop of the region from 1830 to 1890; the center of wheat production was Wisconsin through the 1860s, thereafter shifting westward into Iowa and Minnesota. Wheat farming brought a corresponding increase in the number of grist and flour mills to the area, and coopers were kept busy making barrels in which to ship the flour to market. North eastern Iowa, with its swift streams, furnished the best locations for mills, while the Mississippi River was the primary route to outside markets. As early as 1851 there were several grist and flour mills along the Yellow River. [51]

The impact of the mining industry on the vicinity's economy is harder to determine. There is no record of serious prospecting or mining within the boundaries of the national monument, but with lead deposits abundant on both sides of the Mississippi River downstream from the national monument, it is likely that prospectors carefully searched the area for signs of the valuable lead veins. Two and one—half miles north of Waukon, Iowa, an iron mine operated from 1882 until 1918. [52] However, there are no known mineral deposits on what is today the national monument. Recently, there has been some prospecting on land adjacent to the monument for lead and/or zinc as well as for commercially exploitable limestone, but no mines have opened. [53]

Although the monument was fortunate to escape the effects of mining, it did not escape the ravages of the lumber industry. Timber-cutting in the area began at least as early as 1817 and possibly earlier, as noted above. Cutting trees for firewood was a continuous process from the time of Fort Crawford's establishment until its abandonment, and hardwood for at least the second fort was cut on the military reservation in Iowa. The reservation there measured three miles north to south along the Mississippi River and six miles east to west, encompassing more territory than does the present national monument.

While mills were common in the general area, only one private entrepreneur attempted to make a living from milling near the national monument. In 1840, Jesse Dandley built a sawmill between the site of the former Jefferson Davis mill and the Yellow River mission, by this time a private farm. Dandley gave up the business after a few years of hard luck. There are records of other mills established after settlement began, but they were farther up the Yellow River. In addition to trees cut for lumber, settlers harvested many for firewood for steamboats on the Mississippi River. One operator cut wood on the ridge tops in the north unit and farther to the west, hauled it to the top of the bluff overlooking the river, and dumped it down a V-shaped board chute to the riverbank at a steamboat stop called York Landing. Other woodcutters felled trees on or adjacent to what became the national monument to furnish steamboat fuel to Red House [54] and other landings. [55]

Sometime around the turn of the twentieth century, the national monument was logged over. It is commonly accepted that this was on a "clear—cut" basis, but accurate information on who did this, exactly when, and how much of the future national monument was included is scarce. Many believe that most of the north unit was included, and probably much of the south unit as well. However, loggers cut trees in the vicinity to furnish cordwood to a packing plant where it was used for smoking some cuts of meat in the 1920s and 1930s. It is doubtful that sizeable trees could have grown following a clear-cut in such a short time; thus, the traditional belief that the area was clear—cut may be incorrect. The national monument has been owned by either the National Park Service or the Iowa Conservation Commission since at least the 1940s, and systematic logging of the area has not occurred during that period.

There have been instances of individual trees being removed for personal profit of the poacher. One of the more recent examples of such theft was a walnut tree that measured forty inches at breast height. In a well-planned operation, the poacher felled the tree, cut logs of an appropriate length, and slid the logs under the boundary fence and through a culvert to the river. [56]

In general, where logging of mound areas occurred, it was damaging to the mounds and other historic or prehistoric sites. The operation involved the felling of trees, bucking of logs, skidding them to the loading point, loading them and hauling them away, and discarding the slashings. Each of these activities tore up the ground, drastically rearranging strata so that time sequences cannot be determined. Logging road construction and the skidding of logs probably destroyed several mounds in each working season.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

efmo/adhi/adhi2.htm

Last Updated: 08-Oct-2003