Geological History of Crater Lake

National Park

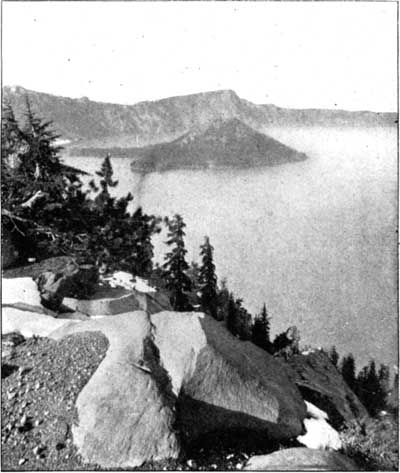

The first point to fix our fascinated gaze is Wizard Island, lying nearly 2 miles away, near the western margin of the lake. Its irregular western edge and the steep but symmetrical truncated cone in the eastern portion are very suggestive of volcanic origin. We can not, however, indulge our first impulse to go at once to the island, for the various features of the rim are of greater importance in unraveling the earlier stages of its geological history.

The outer and inner slopes of the rim are in strong contrast; while the one is gentle, ranging in general from 10° to 15°, the other is abrupt and full of cliffs, as shown in figure 8. This difference is well expressed also by the contour map in figure 13. The vertical interval of the contours is 50 feet. Upon the inner slope the contours are crowded close together to show a slope so steep that one needs to travel but a little way to descend 50 feet, while upon the outer slope the contours are so far apart that to descend 50 feet one needs to travel a considerable portion of a mile. The outer slope at all points is away from the lake, and as the rim rises at least 1,000 feet above the general summit of the range, it is evidently the basal portion of a great hollow cone in which the lake is contained.

FIG. 8—CONTRAST OF OUTER AND INNER SLOPE OF RIM OF CRATER LAKE AS SEEN FROM MOUNT SCOTT.In addition to the strong contrast between the outer and inner slopes of the rim the map shows the occurrence of a number of small cones upon the outer slope of the great cone. These adnate cones are of peculiar significance when we come to consider the volcanic rocks of which the region is composed. The rim is ribbed by ridges and spurs radiating from the lake, and the bead of each spur is marked by a prominence on the crest of the rim. The variation in the altitude of the rim crest is 1,456 feet (from about 6,700 at Kerr Notch to 8,156 feet at Glacier Peak) with seven points rising above 8,000 feet. The crest generally is passable, so that a pedestrian may follow it continuously around the lake, with the exception of short intervals about the notches in the southern side. At many points the best going is on the inner side of the crest, where the open slope, generally well marked with deer trails over beds of pumice, affords an unobstructed view of the lake.

Reference has already been made to the glacial phenomena of the outer slope of the rim. There are scattered bowlders upon the surface, and also in piles of glacial moraine (fig. 9), which contain besides bowlders much gravel and sand. Such glacial drift is spread far and wide over the southern and western portion of the rim, extending down the watercourses in some cases for miles to broad plains, through which the present streams have carved the deep and picturesque canyons already observed on the ascent. At many points the lavas are well rounded, smoothed, and striated by glacial action. This is true of the ridges as well as of the valleys, and the distribution of these marks is coextensive with that of the glacial detritus.

FIG. 9—GLACIAL MORAINE SOUTH OF VICTOR ROCK.A feature that is particularly impressive to the geologist making a trip around the lake on the rim crest is the general occurrence of polished and striated rocks, in place on the very brow of the cliff overlooking the lake. The best displays are along the crest for 3 miles northwest of Victor Rock (fig. 10), but they occur also on the slopes of Llao Rock, Roundtop, Kerr Notch, and Eagle Crags, thus completing the circuit of the lake. On the adjacent slope toward the lake the same rocks present rough fractured surfaces, showing no striae. The glaciation of the rim is a feature of its outer slope only, but, as shown in figure 10, it reaches up to the very crest. The glaciers armed with stones in their lower parts, that striated the crown of the rim, must have come down from above, and it is evident that the topographic conditions of to-day afford no such source of supply. The formation of glaciers requires an elevation extending above the snow line to afford a gathering ground for the snow that it may accumulate, and under the influence of gravity descend to develop glaciers lower down on the mountain slopes. During the glacial period Crater Lake did not exist. Its site must then have been occupied by a mountain to furnish the conditions necessary for the extensive glaciation of the rim, and the magnitude of the glacial phenomena indicates that the peak was a large one, rivaling, apparently, the highest peaks of the range.

FIG. 10—GLACIATED CREST OF RIM OF CRATER LAKE.

Photograph by M. M. Hazeltine, courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.The Mazamas held a meeting in August, 1896, at Crater Lake in connection with the Crater Lake clubs of Medford, Ashland, and Klamath Falls, of the same State. Recognizing that the high mountain which once occupied the place of the lake was nameless, they christened it, with appropriate ceremonies, Mount Mazama. The rim of the lake is a remnant of Mount Mazama, but when the name is used in this paper reference is intended more especially to that part which has disappeared.

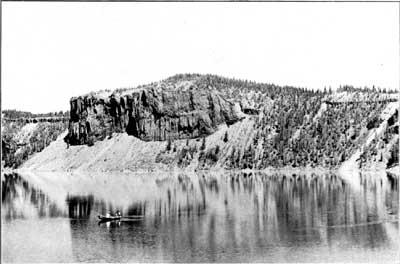

The inner slope of the rim, so well in view from Victor Rock, although precipitous, is not a continuous cliff. It is made up of many cliffs, whose horizontal extent is generally much greater than the vertical. The cliffs are in ledges, and sometimes the whole slope from crest to shore is one great cliff, not absolutely vertical, it is true, but yet at so high an angle as to make it far beyond the possibility of climbing. Dutton Cliff on the southern and Llao Rock on the northern borders of the lake are the greatest cliffs of the rim. Besides cliffs, the other elements of the inner slope are forests and talus, and these make it possible at a few points to approach the lake, not with great ease, but yet, care being taken, with little danger. Southwest of the lake the inner slope, clearly seen from Victor Rock, is pretty well wooded, and from near the end of the road, just east of Victor Rock, a steep trail descends to the water. Where fresh talus slopes prevail there are no trees, and the loose material maintains the steepest slope possible without sliding. Such slopes are well displayed along the western shore opposite the island and near the northeast corner of the lake under the Palisades, illustrated in figure 11. At this point the rim is only 575 feet high, and a long slide, called from its shape the Wineglass, reaches from crest to shore.

FIG. 11—TALUS SLOPE UNDER THE PALISADES UDNER ROUNDTOP. WINEGLASS ON THE RIGHT AND A THIN LAYER OF TUFFACEOUS DACITE NEAR CREST ON BOTH SIDES OF ROUNDTOP.

|

|