Geological History of Crater Lake

National Park

The caldera is completely inclosed, so that it can not be regarded as an effect of erosion. The volcanic origin of everything about the lake would suggest in a general way that this great revolution must have been wrought by volcanism, either blown out by a great volcanic explosion or swallowed up by an equally great engulfment. It is well known that pits have been produced by volcanic explosions, and some of them are occupied by lakes of the kind usually called crater lakes. Depressions produced in this way, however, are, with rare exceptions, surrounded by rims composed of the fragmental material blown out from the depression.

At first sight the rim about Crater Lake suggests that the caldera was produced by an explosion, and the occurrence of much pumice in that region lends support to this preliminary view; but on careful examination we find, as already stated, that the rim is not made up of fragments blown from the pit, but of layers of solid lava interbedded with those of volcanic conglomerate erupted from Mount Mazama before the caldera originated. The moraines deposited by glaciers descending from the mountain formed the surface around a large part of the rim, and as there is no fragmental deposits on these moraines, it is evident that there is nothing whatever to indicate any explosive action in connection with the formation of the caldera.

We may be aided in understanding the possible origin of the caldera by picturing the conditions that must have obtained during an effusive eruption of Mount Mazama. At such a time the column of molten material rose in the interior of the mountain until it overflowed at the summit or burst open the sides of the mountain and escaped through fissures.

Fissures formed in this way usually occur high on the slopes of the mountain. If instead, however, an opening were effected on the mountain side at a much lower level—say some thousands of feet below the summit—and the molten material escaped, the mountain would be left hollow, and the summit, having so much of its support removed, might cave in and disappear in the molten reservoir.

Something of this sort is described by Prof. Dana as occurring at Kilauea, in Hawaii. The lake in that case is not water, but molten lava, for Kilauea is yet an active volcano. In 1840 there was an eruption from the slopes of Kilauea, 27 miles distant from the lake and over 4,000 feet below its level. The column of lava represented by the lake of molten material in Kilauea sank away in connection with this eruption to a depth of 385 feet, and the floor of the region immediately surrounding the lake, left without support, tumbled into the depression. In the intervals between eruptions the molten column rises again toward the surface, only to be lowered by subsequent eruptions, and the subsidence is not always accomplished by an out flow of lava upon the surface. Sometimes, however, it gushes forth as a great fountain a hundred feet or more in height.

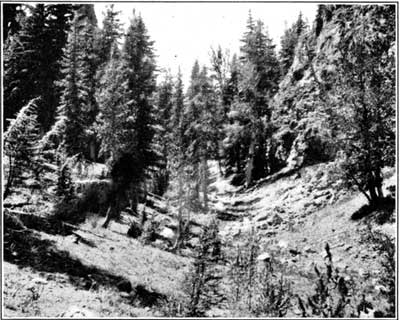

The elevated position of the great caldera occupied by Crater Lake makes its origin by subsidence seem the more probable. The level of the lowest bed of the lake reaches the surface within 15 miles down the western slope of the range. That Mount Mazama was engulfed is plainly suggested by the behavior of its final lava stream. The greater portion of this last flow descended and spread over the outer slope of the rim, as shown in figure 13, but from the thickest part of the flow where it fills an old valley at the head of Cleetwood Cove (see fig. 24) some of the same lava, as already noted, poured down the inner slope. The only plausible explanation of this phenomena seems to be that soon after the final eruption of Mount Mazama, and before the thickest part of the lava effused at that time had solidified, the mountain collapsed and sank away and the yet viscous portion of the stream followed down the inner slope of the caldera. It should be observed also that the lava stream collapsed and formed Rugged Crest, as shown in figure 25.

FIG. 24—A PORTION OF THE COLLAPSED LAVA STREAM AT RUGGED CREST FLOWING DOWN THE INNER SLOPE OF THE RIM.

FIG. 25—COLLAPSED LAVA FLOW OF RUGGED CREST. THE BOLD CLIFFS AMONG THE TREES ON BOTH SIDES ARE REMNANTS OF THE COLLAPSED FLOW.

|

|