Historical Background

WITH the most severe crisis of the Convention behind

them, during the period from July 17 to July 26 the delegates discussed

and more easily settled a number of specifics of the proposed

constitution. It was agreed that the national legislature would "enjoy

the Legislative rights vested in Congress by the Confederation, and

moreover to legislate in all cases for the general interests of the

Union, and also in those to which the States are separately incompetent,

or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the

exercise of individual legislation." But the proposed capability of the

national legislature to negate State laws was dropped. In the upper

house, each State was to have two representatives, who would vote as

individuals rather than as a unit. The national court system was granted

jurisdiction over cases stemming from laws passed by the legislature and

over questions related to national peace and harmony.

Many other issues reached the floor, but did not result in changes to the emerging constitution. These included efforts to empower State legislatures to ratify the instrument, to remove the provision for impeachment of the executive, and to strike appointment by the upper house of judges of the "supreme tribunal."

The matters that proved the most difficult to resolve, even tentatively, in this comparatively harmonious phase of the Convention were those dealing with election of the executive, the length of his term, and his eligibility for reelection. Proposals were entertained and then voted down for election by the people at large, electors chosen by the legislatures, the Governors or electors picked by them, the national legislature, and electors chosen by lot from the legislature. Some delegates suggested that the executive should be eligible for reelection. Others questioned the proposed 7-year term of office. After extensive debate, on July 26 the decision was made to retain the original resolution. The national legislature was to elect the executive for a single 7-year nonrenewable term.

ON July 26 the Convention adjourned until August 6 to

allow a five-member "committee of detail," which had been appointed on

July 24, to prepare a draft instrument incorporating the sense of what

had been decided upon over many weeks. While some of the delegates went

home and others rested and relaxed in or near Philadelphia, the

committee (Rutledge of South Carolina, Randolph of Virginia, Wilson of

Pennsylvania, Ellsworth of Connecticut, and Gorham of Massachusetts)

went about its work. Within a few days, a draft of the constitution was

sent to Dunlap & Claypoole, the firm on Market Street that handled

printing for the Continental Congress, which was meeting in New York

City. The compositor for most of the Convention's work was likely David

C. Claypoole because his partner, John Dunlap, was apparently away most

of the time coordinating congressional printing.

About August 1 a seven-page set of proofs was returned to the committee. After its deliberations, a corrected copy bearing Randolph's emendations, a dozen in number, was sent back to the printer, who incorporated them. By August 6 a first draft of the constitution had been printed, numbering probably 60 copies; it was the first printed rendition of the instrument in any form. The seven-page folio draft, which provided ample left-hand margins for notes and comments, consisted of a preamble and 23 articles. Randolph had apparently prepared a rough draft, which Rutledge and Wilson thoroughly reworked.

The committee conscientiously tried to express the will of the Convention, but also made some modifications and changes that provoked considerable debate. In selecting provisions and phrases, the conferees borrowed extensively from a variety of sources. Of course, the approved resolutions that had sprung from the Virginia Plan provided the basic ideas. But State constitutions, particularly that of New York (1777), and the Articles of Confederation were leaned on heavily, as was also to a lesser degree Charles Pinckney's long-ignored plan. Certain state papers of the Confederation and the rejected New Jersey Plan also provided some of the wording and substance.

The committee necessarily filled in many specifics that various resolutions had left vague or unexpressed. For the first time, names, largely derived from the State constitutions, were given to the members and branches of the National Government: President, Congress, House of Representatives, Speaker, Senate, and Supreme Court. The famous opening phrase of the final Constitution's preamble, "We the People," appeared for the first time, as did such others as the "privileges and immunities" of citizens and the Presidential "state of the Union" message.

Instead of the broad general authority voted to the courts and Congress before the recess, significantly the draft enumerated 18 congressional powers and also areas of jurisdiction for the Federal courts. It likewise listed powers for the Chief Executive, though the Convention's resolutions had laid a precedent for that.

The last and most sweeping of the congressional authorities was the right to make all laws "necessary and proper" to carry out the enumerated powers and all others vested in the central Government by the Constitution. Essentially all the old powers of the Continental Congress under the Articles of Confederation were retained. To them were added new ones, which the majority of delegates felt were essential to correct the defects in the old frame of Government.

|

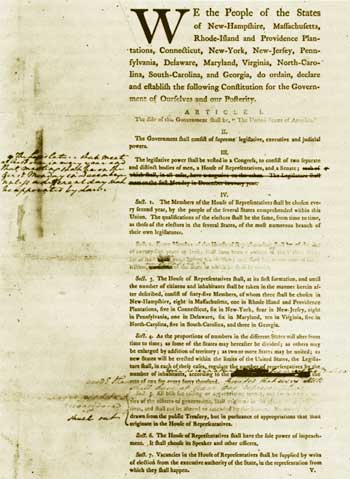

| George Washington's annotated copy of the committee of detail draft of the Constitution The first printed version, it was distributed to the delegates shortly after the Convention reconvened on August 6. Of the 60 copies apparently printed, at least 15 annotated ones have survived in various repositories. (National Archives.) |

Among the new congressional mandates was the most vital one missing under the old system: authority to impose and collect direct taxes of several kinds. Other new powers conferred were the regulation of domestic and foreign commerce; establishment of nationwide rules for the naturalization of citizens; coining and borrowing of money; organization of a national army and navy; authority to call up the State militias; election of a national treasurer; and the quashing of rebellion in the States, with the permission of the appropriate legislatures. Directly contrary to a resolution of the Convention, however, the committee draft specified that the States would pay the Congressmen.

Particular prerogatives of the House of Representatives and the Senate were specified, the principles of their parliamentary organization were outlined, and the privileges of their Members were listed. Some of these provisions were modeled on similar ones in State constitutions. The Senate would appoint ambassadors and Supreme Court judges, make treaties, and participate in the settlement of interstate disputes. The House alone could impeach errant high Federal officials, including the President, and originate money bills. Each House would enjoy a virtual veto on the other, for bills would need to pass both to become law.

In its attempt to define the areas of national authority more precisely, presumably to allay the fears of the less nationalistic delegates, the committee of detail included express restrictions on certain actions by the Legislature. Three of these, apparently reflecting the sentiments of Chairman John Rutledge of South Carolina, were designed to protect the interests of the Southern States. One prohibited the national Government from passing any "navigation act" or tariff without a two-thirds majority of Members present in both Houses of Congress. Another, without employing the word "slaves," forbade the Legislature from taxing or prohibiting the import of slaves or their migration. The third provided that it could pass no law taxing exports. It would also be unable to approve personal capitation taxes except in proportion to the census. The Government as a whole was barred from creating titles of nobility and was limited in the definition it could give to treason.

The Legislature would elect the President for a single 7-year term. His powers were somewhat more carefully spelled out than previously, though not significantly augmented. The most important of these was the veto, though this could be overriden by a two-thirds vote of both Houses of Congress. The Chief Executive would exercise general executive powers for the enforcement of all national laws, appoint key officials except for ambassadors and judges, enjoy the right to pardon, and serve as commander in chief. His responsibilities of informing the Legislature about state matters, making recommendations to it, receiving ambassadors, and corresponding with State executives involved him directly in the formulation of legislative programs and foreign relations. The provisions relating to the Presidency were strongly influenced by State constitutions, especially that of New York.

The committee of detail outlined new prohibitions upon the rights of the States that went far toward establishing national dominance. They were not to coin money or grant letters of marque and reprisal. Without the consent of Congress, they could not emit bills of credit, issue paper money, tax imports or exports, or make agreements with other States. Reiterated were the old Articles of Confederation provisions preventing any of them from entering into independent treaties, alliances, or confederations; waging war independently; or granting titles of nobility.

Relations among the States would be governed by principles of equality, including recognition of the "privileges and immunities" of each other's citizens and "full faith and credit" for official actions. Arrangements were to be made for the extradition of criminals. These measures were virtually identical with similar ones in effect under the Articles, though they had not really ameliorated interstate conflicts. The Federal judiciary now would be in a position to apply these provisions under the new Government.

Another problem the Confederation had not resolved, the admission of new States, was to be handled by admitting them on an equal basis with the original ones, by a two-thirds vote of those present in each House of Congress.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, now also more precisely defined, would include cases arising under U.S. laws; those affecting public officials; maritime and admiralty matters; interstate disputes; and legal contests among citizens of more than one State, between States, and when other countries or aliens were involved. The Court would also try impeachments brought by the House of Representatives.

Although instructed to report property qualifications for Members of Congress, the committee directed Congress to do so itself. A further specification was that qualifications for voting to elect Members of the House of Representatives were to be tied to State law; people who could vote for the more numerous house of the State legislatures were to constitute the electorate for the House of Representatives. In practice, the State regulations on this subject had varied widely and a uniform formula would have not only been difficult to devise, but might also have seemed to intrude too much on State authority. In the vexing matter of the number of States required to approve the Constitution before it became the law of the land, the committee simply left a blank. The Convention would have to decide.

Demonstrating considerable skill and energy, the committee of detail had performed creditably, though the degree of the changes and innovations it had made apparently surprised the delegates. Its services were not completely done and it reported to the Convention from time to time later on, when difficult matters were referred for its consideration.

The Convention reconvened on August 6. Either on that day or the next the delegates received individual printed copies and began to consider the first draft of their handiwork.

FIVE weeks of intensive discussion were required to

revise the raft constitution. These weeks were tedious and debilitating

for the delegates. The weather, in a day of no air conditioning, was

miserable. Many of those in attendance had been away from their families

and professional duties since May. All wanted to finish and go home. In

fact, as time passed, the pressure of personal business and other

factors, including dissatisfaction with the course of the proceedings,

lured a few more individuals away from Philadelphia, beyond those who

had already departed.

Those who stayed became increasingly anxious to finish their work. In mid-August lengthened sessions were briefly experimented with, but this proved to be unsatisfactory, for they interfered with the dinner hour. Speeches tended to become more concise and the spirit of compromise intensified. And more and more the strong nationalists—Madison, Wilson, and Gouverneur Morris among the leaders—gained the dominant voice. As the draft constitution was studied article by article and line by line, much debate occurred, mostly on a high level, though some of it was tedious and inconsequential. The process had to be endured, however, and many significant changes emerged from it.

The question of the number of Representatives proved to be a source of difficulty. The committee of detail had specified one in the lower House for each 40,000 inhabitants. Madison, objecting, contended that as population increased that body would grow to an unwieldy size. The States voted unanimously to change the wording of the provision to read "not exceeding the rate of one for every forty thousand."

Another matter attracting much attention was the citizenship and minimum residency requirements for Senators and Representatives. The committee of detail had proposed 3 years of citizenship for Members of the House and 4 years for the Senate. Fearing new residents might be too much influenced by their foreign background, the delegates increased the figures to 7 and 9 years, respectively.

Countering its earlier instructions to the committee of detail, the Convention refused to prescribe property qualifications of any sort (either land or capital) for Federal officeholders, though most States specified such requirements for both voting and officeholding. Although Charles Pinckney and Gerry argued for such restrictions, the Convention accepted Franklin's reasoning that they would debase the "spirit of the common people." Pinckney, however, was responsible for the motion barring religious tests for officeholding; these were also a common feature of State laws.

The committee of detail had revived the question of who should pay Congressmen. By a large majority, its suggestion that the States do so was revoked, and the Convention's earlier resolution that they be compensated from the national Treasury was reinserted.

Added to the congressional powers granted by the committee draft was the vesting of the Legislature with authority to declare war. Gouverneur Morris argued strenuously against the provision giving the national Government power to "borrow money and emit bills." He held that the "Monied interest" in the Nation would oppose the Constitution if paper money were not prohibited. Because the Government would enjoy the capability to borrow money and presumably to use public notes, the delegates heeded Morris' objections and struck out the phrase. A limit on congressional tariff powers also won approval. It specified that tariffs would need to be uniformly and equally applied throughout the country.

|

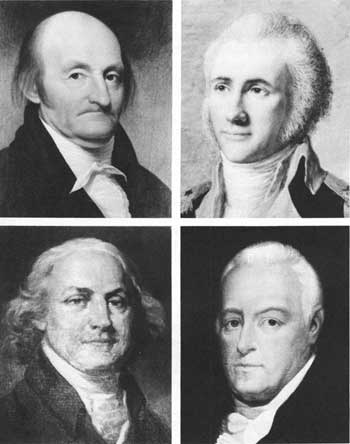

| Four of the 55 delegates to the Convention who departed early and did not sign the Constitution. Upper left, James McClurg; upper right, William R. Davie; lower John F. Mercer; lower right, John Lansing. The first two men supported ratification, and the latter two opposed it. (McClurg, detail from oil (ca. 1810) attributed to Cephas Thompson, Julia Wickham Porter and Charles W. Porter III; Davie, detail from miniature, oil on ivory, by Eliza L. Mirbel, Independence National Historical Park; Mercer, detail from oil (1901) by Albert Rosenthal, after a miniature by Robert Field, Independence National Historical Park; Lansing, detail from oil (ca. 1814) by Ezra Ames, New York State Court of Appeals.) |

The Great Compromise had included a clause stating that money bills should originate in the House of Representatives and not be subject to Senate amendment. Many delegates had entertained serious reservations about this provision. It had been borrowed from colonial and State procedures, which had not always worked well. The issue came up twice in early August during debates in which many delegates participated, but the Convention, after tentatively resolving it twice again, found it so dangerous that it threatened to overturn the entire Great Compromise. Final consideration of it was postponed until the powers of the Senate might be considered.

Several delegates argued vociferously that the national Government must assume the State, as well as National, or Confederation, war debts, on the grounds that they had all been incurred for the common good during the Revolution. Opponents of this proposal contended it would benefit speculators rather than legitimate debt holders. Some controversy also arose between some of the States that had paid off substantial parts of their war debts and some of those that had not. The question was hotly disputed because it involved Congress taking over the States' power to tax imports, a major source of their income. An assumption of State debts would lessen the reluctance of creditor interests in the States to support the new Constitution. The matter was referred to a special committee, composed of one member from each State.

After that group reported a compromise, which was followed by another frustrating debate, the delegates approved an amended version which merely stated that "all debts contracted and engagements entered into, by or under the authority of Congress shall be as valid against the United States under this constitution as under the confederation." This ambiguous wording avoided the difficult question of exactly what debts were valid against the Confederation.

A recommendation to give the national Government power over the State militias touched on the vital matter of States rights and on the Continental Army's troubled dealing with the militias during the Revolution. The dispute was so grievous that a committee was instructed to bring in a solution. It was proposed that the national Government be empowered to pass laws requiring uniform militia organization from State to State and comparability of arms and discipline. The Government also gained the power to control units called into Federal service. The States retained the right to train their own militias and appoint their own officers. These recommendations were accepted without amendment.

One of the sharpest exchanges of the Convention occurred toward the end of August over slavery and the committee of detail's plan to protect the import slave trade and prohibit Federal taxation of it. This was an explosive issue. Some northern delegates and Mason of Virginia objected to slavery and/or the slave trade on moral grounds; others saw more practical Considerations. Luther Martin pointed out that prohibition of an import tax on slaves meant lack of national control over the traffic and provided a possible incentive to the Southern States to augment their representation by adding to their slave populations. The power to tax could, on the other hand, be used to discourage or prevent the import of slaves, and southerners tended to oppose this. Mixed into this debate and into that on the regulation of foreign trade was the matter of divergent economic interests in the States. A related problem involving southern-northern conflict was the specification in the draft constitution that a two-thirds vote would be necessary to pass navigation acts.

After many delegates had expressed their opinions, the unresolved matters of slave import regulation, Federal taxation of it, and the navigation acts were turned over to another special committee, consisting of one member from each State. Complicating solution of this issue still further was the Northwest Ordinance, which the Continental Congress had passed the preceding month. By providing that States formed north of the Ohio would be free of slavery, the ordinance touched on an argument that later would be of great significance, the status of that institution in new Territories and States. Any compromise would presumably need to heed this new legislation.

The committee presented a complicated compromise. Congress could not act to prohibit the import of slaves before 1800 into States that had existed in 1787, but might tax such importation at an average rate compared to that for other imports. The committee also suggested that a simple congressional majority should be sufficient to pass navigation acts.

|

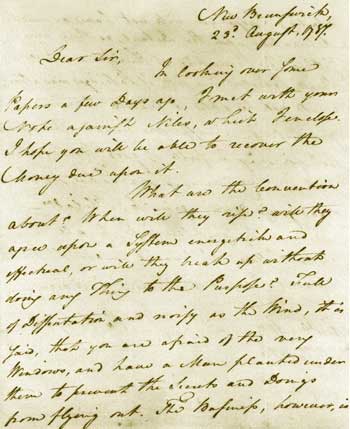

| As the summer dragged on, many delegates questioned whether or not the Convention would ever reach agreement. In this extract from a letter written on August 23, 1787, by William Paterson from his home in New Jersey to fellow-delegate Oliver Ellsworth (Connecticut), the former wonders: "What are the Convention about? When will they rise? Will they agree upon a System energetic, and effectual, or will they break up without doing any Thing to the Purpose?" (Historical Society of Pennsylvania.) |

The portion of the compromise dealing with the trade in slaves underwent modification. Congress was instructed not to forbid the traffic prior to 1808 (again for those States existing in 1787) and a specific limit was set on the taxes that might be imposed on it.

Over the objections of Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, the part of the compromise concerning slavery was accepted. Both sides probably privately considered the result a victory. Antislavery delegates felt they had succeeded in writing into the Constitution a provision that could ultimately end the importation of slaves. Proslavery delegates hoped that agitation against the slave trade might disappear after a moratorium of two decades.

Simply to have made it possible to act against the slave trade at that future time was as substantial a victory as the antislavery men at Philadelphia could win in view of existing political realities. The Southern States would have rejected any major restrictions on slavery, and the Northern would compromise no further, though they soon accepted without protest a provision for the return of fugitive slaves. The stipulation that abolition of the slave trade could be considered after 1808 at least demonstrated that the founders were not all immutably subscribing to the system and that future action against it was not precluded.

Indicative of the gingerly manner in which the topic was treated in the Convention, the words "slave" and "slavery" do not even appear in the final Constitution, where slaves are referred to by such euphemisms as "other persons." As a matter of fact, the subject is touched on in only a few places. Articles I and II prevent Congress from outlawing the import trade in slaves until 1808. And existence of the institution is acknowledged in the "three-fifths" clause dealing with representation (Article I), as well as in the stipulation for the extradition of an escaped "Person held to Service or Labour" (Article IV).

Had the delegates not handled the issue so carefully and obtained the support of all sections, the Convention would probably have dissolved over it. On the other hand, the compromise brought the moral price of the Constitution to a high level.

The second part of the compromise dropped the two-thirds requirement for adoption of navigation acts by Congress. In some ways, acceptance of this provision represented a greater potential sacrifice for the South than most other compromises of the summer. As a region producing an abundance of staple crops that needed to export surpluses, it was fearful of granting the general Government power to tax imports and exports. Randolph and Mason of Virginia were worried, prophetically as it turned out, that if northern commercial and manufacturing centers gained in population and power they would enact taxes and other measures destructive of the southern economy.

A number of southern delegates, however, failed to heed their two colleagues and voted for the compromise. The Southern States were probably conciliatory on this issue because they had earlier won exemption of exports from Federal taxation. Many southerners also believed that the future would bring rapid expansion to the agricultural sections of the country and that the South and West, as economic allies, would be able to prevent the commercial States of the Northeast from dominating the Government. The future would prove them wrong. The Northern States were content with this part of the complex compromise because it would allow them to pass commerce legislation more easily than they had anticipated.

|

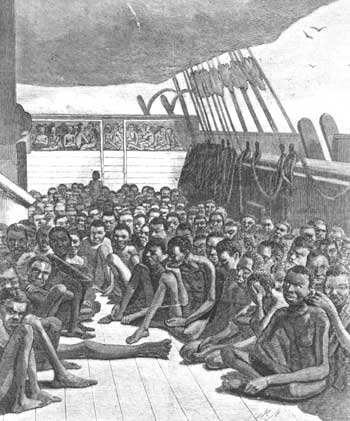

| After considerable debate and acrimony, the Convention delegates compromised on the issue of slavery. Continuation of this moral evil was to lead to national schism and the Civil War. (Engraving by an unknown artist, after a daguerreotype in Harper's Weekly (June 2, 1860). Library of Congress.) |

New prohibitions on congressional action suggested and approved by the full Convention while reviewing the draft of the committee of detail included ones against bills of attainder, ex post facto laws, and suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in peacetime. Troubles in trying to agree on the powers of the Senate caused postponement of action on this matter. The delegates did strike out its role in the settlement of interstate disputes, and passed this to the Supreme Court. The authorities of the House of Representatives gave rise to little controversy during this period of the debates.

The veto power of the President was also enhanced. Williamson moved, and the delegates endorsed, a three-fourths vote of each House to override the veto of the Executive. This move was undoubtedly motivated by a desire to increase his independence from the Legislature, which was at this point still slated to elect him.

Late in August the Convention once again debated election of the President. Misunderstanding arose over the method of casting the legislative ballot. The delegates proceeded to approve a joint vote by the two Houses, rather than separate ballots by each of them. The small States protested because they felt this decision would virtually give the power of election to the large States, whose contingents in the lower House were strong.

Unable to resolve this problem readily, the Convention returned to discussion of the President's powers, largely going along with the original committee of detail's proposals. Adopted from a supplementary committee report, on August 22, were provisions that the President should be 35 years of age and a resident for 21 years. A suggestion in this same report that the President enjoy the advice of a privy council of Cabinet members and top legislators died without formal consideration.

Occasioning only brief discussion was jurisdiction of the Federal courts. It was extended far beyond what had been granted by the committee of detail, which had given them power only over cases arising under Federal legislative acts. This was now amended to include all cases arising under the Constitution which was to be the "supreme law."

Curiously, the right of the Supreme Court to pass finally on the constitutionality of laws, treaties, and Executive actions was not explicitly stated, though many of the delegates apparently understood that it would exercise such authority. On one matter previously assigned to it, the trying of impeachments, the committee postponed a decision.

Anxious to assert exclusive national authority over what they deemed to be vital matters, the delegates not only approved committee limitations on the States, but also imposed certain additional ones, especially a prohibition on the issuance of paper money.

The admission of new States was also a provocative issue. The committee of detail had proposed that they be admitted as equals with the older ones by a two-thirds vote in each House. Gouverneur Morris, who had previously argued that the preponderance of power must remain with the original seaboard States, renewed his objections. Despite cogent rebuttals from Madison, Mason, and Sherman, he persuaded the Convention to alter the committee's proposal. The statement "New States may be admitted by the Legislature into the Union" was then unanimously substituted. Morris long remained convinced that it really meant the Eastern States would govern much of the West. So noncommittal was the language, however, that future Congresses were to interpret it to mean that a virtually unlimited number of new States could be brought into the Union as equals of the original ones.

Provisions relating to interstate relations, which the committee of detail had largely adapted from the Articles of Confederation, met approval with minor changes. Included were the extradition of criminals and the return of fugitive slaves, as well as State recognition of each other's legislative and judicial actions and the "privileges and immunities" of citizens. Also adopted was the committee of detail proposal that when two-thirds of the State legislatures applied to Congress for an amendment to the Constitution a conventioner would be called to consider it.

As for the number of States required to ratify the completed Constitution, the committee of detail had left the number blank. Ideas on this issue ranged from proposals that all 13 must express their approval, as the Articles of Confederation required, to suggestions from Madison, Wilson, and Washington that a bare majority, seven, would be sufficient. Nine was finally chosen as the proper number. This action demonstrated a crucial break with the Articles of Confederation. The delicate matter of the role of the Continental Congress in the ratifying process also caused debate. The delegates boldly resolved to submit the Constitution to it with the recommendation that the instrument simply be forwarded to conventions in the States.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/constitution/introe.htm

Last Updated: 29-Jul-2004